Commodore Advert - November 1987

From Your Computer

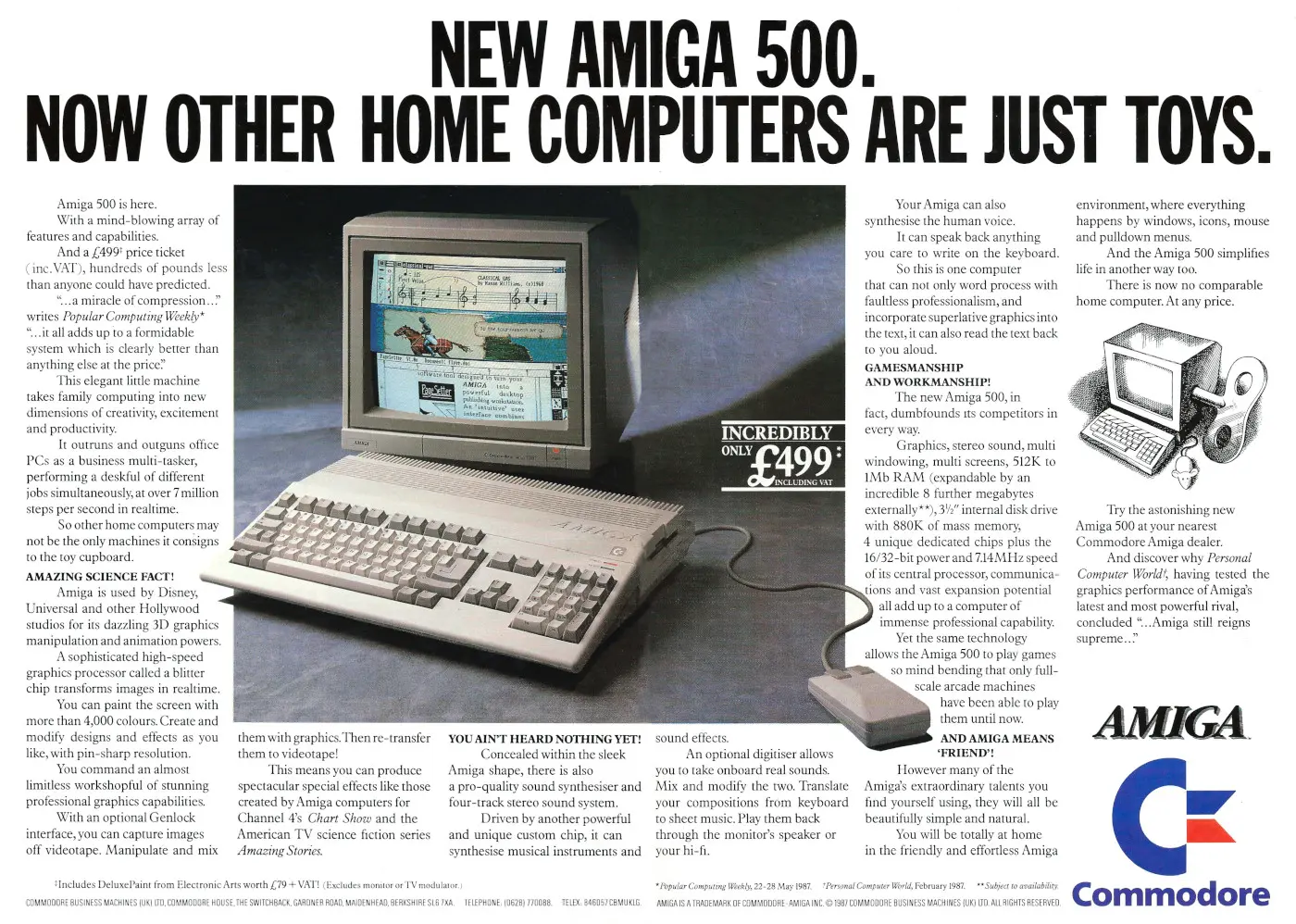

New Amiga 500 - Now other home computers are just toys

The original Amiga, or A1000 as it came to be known, nearly didn't make it when it launched in 1986, as Commodore was going through some major financial problems whilst its potential saviour machine was being increasingly delayed.

Even after it launched, no-one was sure whether developers would actually produce any software for it, and even Commodore didn't seem that convinced by its own product as it shipped without the company's logo on the front of the machine.

Commodore did however survive its financial scare and went on to produce several subsequent Amiga models, including this - the Amiga 500 - a model which saw a return to Commodore's tradition of selling through mass-market retail outlets, a move which enabled the 500 to become the best-selling Amiga model[1].

In the US, the Amiga had finally started making some headway in the market and appeared to have contributed to Commodore International's financial turn-around, with the company going from a loss of $53.2 million in the second quarter of 1986 to a profit of $21.8 million in the same quarter in '87[2].

However, in the UK, Commodore's Amiga marketing had not worked particularly well and sales were low - factors which perhaps explained the unexpected "resignation with immediate effect" of Commodore Europe big cheese and one-time general manager of Commodore UK Nick Bessey, who left to go to an IBM dealership in New Zealand.

Amigas had previously been considered overpriced and definitely not mass-market, even though any mention of the machines were nearly always accompanied with words like "excellent" and "wonderful"[3].

At around this time, parent company Commodore International Limited (CIL) announced that it had signed a major deal with arcade-machine builder Bally, which would allow Bally to develop a whole new generation of coin-operated arcade games based on the Amiga.

As part of the deal, Commodore would receive software rights to anything developed, in return for the Amiga's graphics capabilities - the key to the deal being the three co-processors that made the Amiga so good: Agnus, Denise and Portia, plus 1.5Mb of ROM for game code - and Commodore's technical know-how.

Commodore's US general manager Nigel Shepherd suggested that "this association will particularly enhance the value of the soon-to-be introduced A500" whilst Bally's Roger Keesee said:

"The Amiga's ability to generate over 4,000 different colours, plus special effects capabilities can provide for substantially improved high-resolution graphics, not only in our games systems but in our other video products"[4].

A few weeks later, games company Mastertronic announced that its arcade cabinets also contained the same Amiga-based "B-52" boards.

Recently launched in the US under the Arcadia Systems subsidiary, Mastertronic was a new entrant in the competitive arcade games market and was now a direct competitor with Bally.

Mastertronic's Geoff Heath was somewhat pragmatic about this situation, suggesting that "[Bally is] a multi-million pound company, and we're still working on it"[5].

Finally, the affordable Amiga

When Commodore first launched the Amiga, it had believed that it could become the business PC of the future, although as it happened it was really ahead of its time and that future was still a couple of years away.

Not only that, but it turned out that companies like Ashton-Tate, Lotus and Microsoft were also less than interested in converting their business applications to run on the new platform, especially whilst their target market seemed happy spending its cash on dull but functional text-based programs for equally dull-but-worthy IBM PCs.

It wasn't until the middle of 1988 that the concept of the "graphical" business computer seemed to be taking off, partly thanks to the presence of Apple's Macintosh, but also because of Microsoft's OS/2 Presentation Manager - a windowing system that would finally make PC's look like Macs.

There was also former Apple founder Steve Jobs's NeXT graphical workstation on the scene, said to be the power user's PC of tomorrow and available for a snip at around $10,000[6].

Frank Herman of Mastertronic, © Popular Computing Weekly, December 1987Even though the market was finally heading towards graphical computers, it really took the release of the A500, which was essentially an A1000 at less than half the price, to make the Amiga affordable enough to take on its closest competitor - the Atari ST - and finally kick off the company-saving sales Commodore had been staking its future on.

This was borne out by various comments from leading non-business software houses of the day, including Mastertronic's chairman Frank Herman who said:

"I think the A500 is a very sensible move - it makes the Amiga more affordable. We're developing Amiga product, in fact we're already fully committed to it".

Leigh Richards of Creative Sparks was a little more cautious, suggesting that:

"It's early days yet. It's a significant launch, certainly, and will encourage development of software. The Amiga is a super machine".

Enthusiasm seemed to split along geographic lines, with companies in the UK, where the 16-bit market was still in its infancy, being more wary.

Ian Stewart of Gremlin reckoned that "The ST has opened the market. The Amiga is a superb machine, but it is still too expensive as a games machine for Europe".

Mirrorsoft marketing director Pat Bitton pointed out one of the issues for smaller UK software houses was that "Software for the 16-bit machines has to be done on an international scale, because of the high development costs"[7].

Popular Computing Weekly was another publication that, even after the price cut to £500, reckoned that the Amiga was still too expensive.

In an article defending the magazine's seemingly pro-Atari ST stance, Peter Worlock suggested that

"Yes, the Amiga is a great machine. Technically, it may even leave the ST for dead. But, assuming [we] speak for the silent millions, I would say: I'd love an Amiga but I can't afford it. Maybe you can do wonderful things with its graphics, but a Sun Apollo workstation does 'em better, and I can't afford that either".

He continued by comparing the similarity of the price of an ST to that of the mass-market Commodore 64 a few years earlier, before suggesting that no computer at the Amiga's £500 price point had ever sold in large quantities in the UK and concluding

"We're not being paid by Atari, we're paid by thousands of computer owners every week who expect hard facts and informed opinion. Our informed opinion is that, for the ordinary computer enthusiast, the ST currently represents a better buy"[8].

The Amiga 500 ended up becoming the world's best-selling home computer throughout the ealy 1990s, although it was a slow start, selling only 12,000 units in its first year.

However, by the time it was replaced by the A600 in 1992, it had sold over one million units in the UK alone[9].

The Amiga grey market

The A500 also seemed overpriced if the grey market was anything to go by, as by October 1987 Commodore was having to warn UK users against buying discount 500s which had been imported "without Commodore's knowledge" and which had been made available via "unauthorised dealers and distributors".

The machines appeared to be European models rated at 220V, which although close enough to the UK's 240V supply[10], were not approved: if anything went wrong it was tough luck as Commodore would only warrant machines in their country of origin[11].

First signs of a grey market had appeared at least a month before this when it had been noted that poor sales in Germany and Europe might have been the source of the dubious import market, as dealers sought to dump their machines.

The UK was in the midst of an Amiga turn-around following a voucher promotion, which offered £100 off an Amiga or £200 off a bundle including the 1081 monitor, the effect of which was to bring the Amiga 500's price down to £399 - the same as the 1981-vintage BBC Micro.

Although Commodore UK's consumer sales manager Tom Hart suggested that the company had "no plans to do anything with the price of the A500" and that "[the offer] will end on the 12th September", Popular Computing Weekly was forecasting a price drop to £299 plus VAT before Christmas whilst Amiga distributor Zappo Computers' chairman Don Carter had been staggered by the effect of the promotion, saying "A500 sales are currently phenomenal.

The Amiga has moved from being a product that was important to us, but frankly didn't sell very fast, to being a product that is currently our fastest-selling computer".

Popular Computing Weekly observed that retailers in Germany - where the grey imports appeared to be originating from - might want to press Commodore for a similar promotion over there[12].

The grey imports issue rumbled on for a while, and mirrored a similar "crisis" 18 months before when there had been a threat of a wave of imports of Sinclair Spectrums from Brazil.

As more stories of "dodgy computers" started to appear in the press, Commodore was poked in to action, although the company admitted that the machines, which had initially been described as outright "fake" and which Commodore's UK Consumer Division's Tom Hart had said were coming from "unscrupulous dealers who cannot get a Commodore dealership and are trying to make a fast buck"[13], were still perfectly legitimate machines having been produced at the company's Braunschweig factory in Germany[14].

The "grey" machines were all European spec with round-pin Euro plugs and everything and even came complete with bogus UK warranty cards, albeit fake ones printed with a non-Commodore luminous red ink.

Commodore's new UK boss Steve Franklin - who started in July 1987[15] and who was the latest in a string of managing directors, as Commodore seemed to be continuing the "revolving door" staffing policy popular during the Jack Tramiel years - was forced to admit that Commodore could take little action over the incident, whilst still suggesting that customers should be careful.

Zappo Computers popped up again as its chairman Don Carter defended Commodore's position by suggesting that:

"Under the treaty of Rome we are in a free market, so there is no reason why products shouldn't be imported into this country from Europe. Commodore would stand in contravention of the treaty if it tried to stop those imports. Obviously Commodore [isn't] thrilled that someone in Europe is screwing up their market, but on the other hand have a duty to warn people that these products are not UK products. The technical subtlety is of significance - these products coming in from Europe have not been through UK quality control, so there is every possibility that they will be more prone to failure".

The upside of the whole issue was that it did seem to have spurred Commodore into addressing its Amiga pricing, in order to compete with the "unofficial" grey Amigas. Carter pointed out that:

"in the early days, the Amiga didn't sell well Europe-wide. All the companies had targets to achieve, and some dealers and distributors tried to engineer prices which resulted in the machines coming in at silly prices. Commodore UK put a stop to it, and the only reason that the grey imports have ceased is that the promotion that Commodore UK is offering is better than the price of the grey import. Grey imports prosper when there is a market for them"[16].

The dawn of the computer virus

Towards the end of the year, Commodore was in the embarassing position of having to publicly admit that it was suffering from an early computer virus - the Amiga's first - having previously dismissing rumours of the SCA Virus as a hoax.

However, it couldn't actually be arsed to do anything about the problem until it considered that the situation was out of control, with a spokesman suggesting that

"it's not serious at the moment. As soon as someone thinks it's got out of hand, they'll take action. Commodore will do all it can to get rid of it - they've just got to obtain the anti-virus disc".

Whilst the Guardian newspaper was warning users of other machines not to borrow discs, the readers of Popular Computing Weekly were already suggesting fixes, which seemed to involve nothing more than over-writing the boot sector on each floppy affected[17].

The Amiga's first virus, courtesy of the "Swiss Cracking Association", seemed to open the floodgates as countless others rapidly followed.

Most at the time seemed to be similarly bootloader based and so spread quickly as the Amiga - or Amy as it was being called - had a particularly large Public Domain Software user base.

This meant a lot of disk copying between users, and even between computer shops using public software, all of which presented an opportunity for up to 1024 bytes of dodgy boot code to spread rapidly.

Although some of these viruses, with names like SCA and Byte Bandit, were intended merely as rogue advertising where destroying disk data was simply an unintended side-efect, the problem was clearly bad enough that by 1988 it had spawned the creation of an entirely new form of software: the anti-virus tool.

In a neat sort-of circular reference, several of these tools were also available as Public Domain (i.e. free), and one of them - VirusX from Steve Tibbett - even provided its own source code, so the really paranoid could inspect it and even recompile it if they felt like it.

This anti-virus tool also seemed to set the precedent for the way that most future virus checkers would work - it didn't just recognise changed boot sectors, but could recognise the various signatures of several known viruses of the day, even the ones that didn't have obvious ASCII messages like "Your Amiga is alive!" in them[18].

It wasn't just one-person operations that were churning out anti-virus software, as companies that would become famous in the as-yet-to-appear Windows market, like Symantec, were already established, with the US company opening up a UK presence in the summer of 1989.

In the upside-down parallel universe of the late 1980s, Windows wasn't yet well established and so it was the Mac operating system that appeared to be the most popular virus vector, primarily because it was a homogenous system which was completely consistent - and so easier to target - unlike the PC world where, as Guy Kewney in Personal Computer World quipped, "there's no guessing about whether some clever idiot has written their own disk control software, or what address the display starts at".

Symantec's program - Symantec Anti-Virus For Mac, or SAM - claimed to be able to stop all documented Mac viruses at the time, including Scores, nVir, Hpat, Init29, Anti, AIDS and MEV[19].

Byte Bandit itself, meanwhile, had managed to singularly unimpress the Amiga user community at large, with Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World suggesting that it showed the author's "incompetence as a programmer".

This was because it turned out that Byte Bandit had a bug, with one user of the user group lamenting that a copy of the virus they had got to test simply didn't work, to which another wag responded that they should "call Byte Bandit and ask for an upgrade".

A couple of software companies - Microdeal and BT's Rainbird - had had the virus show up on their disks, although neither suffered any serious harm, with Rainbird saying that it caught most of the infected disks before they reached any customers - althought it still ended up sending 15,000 infected disks to its US Amiga customers[20].

Meanwhile, MicroDeal's recent software actually wiped all memory clean on load, so the virus would be removed anyway, whilst the Commodore User Group was suggesting an anti-virus program called Viewboot, written by Brian Meadows and which was available in the public domain[21].

Robert Popp and the first Ransomware

The AIDS virus (of the computer variety) had been created in 1989 by Harvard-trained evolutionary biologist Joseph L. Popp[22].

Popp sent 20,000 disks containing information on AIDS to 20,000 targets on a mailing list apparently bought on the black market for £900.

However when loaded the disk would actually plant a time-bomb virus of its own which, upon activation, would hide files and directories on the victim's hard disk useless they sent money to Panama, in what was the first ever ransomware attack.

The AIDS trojan virus waited for 80 reboots of the host system, which took on average two months, to strike, and the hope seemed to be that enough disks would have been swapped around and copied between friends that a much larger number of systems would be infected before word got around in the press to warn people what was going on.

However, on the day the disks went out, a message about them appeared on the Compulink forum of Surbiton's CIX conferencing system, which prompted others to check for disks, and before long experts were being contacted and research started.

Within 12 hours the news had made it onto local London radio as CIX members started contacting the media, and within the day it was headlining the London Evening Standard.

Before the next day, virus hunters Jim Bates and Alan Solomon knew how the virus worked, and the following night, apparently fuelled by coffee, Bates had written a program to remove the trojan and fix the damage.

By the evening of the first day - now called zero day - even the New York Times had wind of the story, thanks to the Unix-based Usenet system.

Information was also bouncing around California, Belgium, Sweden and Zimbabwe - word had got around so quickly that the only people to actually get infected was a small group of computer users within ICL[23].

Popp, who had avoided prosecution by wearing a condom on his nose "to avoid radiation" and thus had been declared unfit to plead, was also found guilty in absentia of extortion by a court in Italy, which sentenced him to two and a half years in prison.

It doesn't appear that he was ever extradited to face this, plus an additional 50 additional charges, as he remained in the US where he had been imprisoned following his arrest at Amsterdam's Schipol Airport.

He was eventually released thanks to his novel condom use and died in 2007 without ever revealing his motives for releasing the virus[24].

Date created: 24 January 2024

Last updated: 17 December 2025

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.