Commodore Advert - April 1987

From The Sunday Times

Never in the history of business systems has so little done so much

Both the "budget" Amiga 500 and higher-end A2000 were announced at the same time during the winter CES show in Las Vegas in 1987.

However, Commodore actually managed to start shipping the A2000 several months before its cheaper sibling, and several weeks before it was actually due.

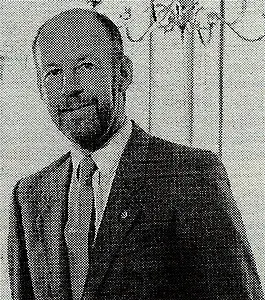

Chris Kaday - managing director of Commodore UK - was not unsurprisingly claiming that the move was as a result of the response to the launch by dealers and members of the public. He also said that "We are delighted to be shipping the new A2000 early following a positive press from this month's launch" and reckoned that Commodore was now "ready to fulfil [the public and press's] expectations"[1].

Chris Kaday, managing director of Commodore UK, © Popular Computing Weekly, May 1986In early April, Chris Kaday suddenly resigned, prompting speculation that his disappearance had been demanded by Commodore's European headquarters.

Kristian Andersen, Commodore UK's marketing head, dismissed these rumours as "fairytales" (geddit?), saying, not entirely convincingly, that "It's not dramatic. It was just one of those things. Chris just thought he'd prefer to go for other opportunities".

The rumours in the press however were that Kaday had been "asked to leave" following concerns from Commodore's president Tom Rattigan about Commodore UK's prospects, with Rattigan having stated that "the UK market's been a real problem for us over the past year".

Those "problems" were primarily the lack of Amiga 500 and 2000s, which left Commodore UK without any new models to sell, unlike the rest of Europe.

Beyond the mystery disappearance of Kaday, Andersen also took some time out to diss the company's own PC1 - a single-floppy-drive MS-DOS-based entry-level PC aimed at the home market. Andersen said of it that:

"The PC1 is a downgrade of our PC line. There seemed to be an interest in a product like that so we built one and showed it at Hannover. I'm not very convinced that people will buy it - for one thing MS-DOS will bore the home computer market stupid".

The sense of having to build crummy IBM clones to satisfy a perceived market need seemed to be quite common at the time - Commodore's founder and now CEO of Atari, Jack Tramiel, had been as dismissive of his new company's own PC entry as Andersen was of Commodore's attempt[2].

Kaday had also been skeptical about the PC1, suggesting that:

"If the PC1 can be released at the right price then we in the UK will participate. But, we feel we've just launched two very exciting products in the [A500 and A2000] Amigas and we don't want to distract too much attention from them".

Maybe Kaday's sense of independence was getting too much for Commodore HQ, as he went on to suggest:

"The whole question of price is academic. We will announce the UK price at the time of launch, but the machine is not yet in production. Commodore UK is focusing on product that is shippable"[3].

Commodore UK had appointed Steve Franklin, former Rank Xerox alumnus for 11 years and sales and marketing director of Granada Business Centres for the last three years, as its new general manager, three months after the departure of Chris Kaday.

UK operations, partly thanks to Kaday's slimming operations over the previous year which included the closing down of LCD watch and game manufacturer Commodore Electronics, had become something of a minor offshoot of CBM Europe in Frankfurt.

Power was becoming increasingly centralised in West Germany, with local chief Ernest Tarien reporting directly to Commodore International's chief exec Irving Gould.

Popular Computing Weekly was even questioning whether Franklin would simply become a puppet of the European operation - a sad end to the years when Commodore UK was the absolute jewel in the whole of Commodore's European crown.

By 1991 Commodore Germany had taken over the UK's "top slot" in the company's world sales, not just by numbers of Amigas sold but also by selling more-expensive models. Even Commodore's PC range was doing better[4].

Meanwhile, Franklin was due to start in his possibly-powerless poisoned-chalice role on the 1st July 1987[5].

Within a few weeks, he was interviewed in Popular Computing Weekly and kicked off by suggesting that his plan was to "put Commodore back on the map", referring indirectly to the company's recent string of disastrous financial results and reduced sales.

He also explained the continuing existance of the now-five-year-old C64, justifying its positioning as an entry-level machine "for some time" on the grounds that it was cheap and it had a massive software base.

This was broadly true, except that the price of £388 for a 64 with disk drive didn't exactly compare well to the Atari 520STFM's £299.

It looked like a price cut had to be one the cards, with Franklin suggesting that "Come September, [you will see] some very attractive buys on the C64".

He seemed less convinced about the company's C128 and C128D, hinting that "there is a question as to whether they're competitive", but he was also keen to rule out a return to the vicious price wars of 1983:

"I will never get into a price war. It's bad for the industry, bad for dealers and ultimately it's bad for the end users, because if companies keep cutting their prices, then something will have to give, and that something will be quality".

The threat from Brentwood

As well as Atari, Franklin also acknowledged the presence of Amstrad, pointing out that when a home user wanted a serious machine, the choice was "Amstrad, Amstrad or Amstrad".

Here too was a willingness to avoid a price war on a second front, as Franklin stated that Commodore didn't want "to start a war with Amstrad, we simply want to provide an alternative".

Popular Computing Weekly concluded that whilst wanting to avoid a war was understandable, "standing between Alan Sugar [of Amstrad] and Jack Tramiel [of Atari] is to place yourself squarely in the combat zone"[6].

On the 16th April, not long after Kaday's departure, Thomas Rattigan was sacked by Commodore, but this time it wasn't until October - a full seven months later - that chairman of Commodore International Limited, Irving Gould, had found a replacement in the oddly-named Max E. Toy - apparently a well-known figure in the computer industry who had previously held jobs at IBM, ITT and Compaq.

Rattigan, a former PepsiCo executive (echoing Apple's recruitment of John Sculley to replace Steve Jobs), had been hired to replace Marshall F. Smith, who had held the post for only two years since Jack Tramiel's departure.

Rattigan had re-established some trust with Commodore's bankers, who were said to have preferred his style and success in giving Commodore some product stability to Gould's hard-nosed approach.

Gould, whose Canadian non-domiciled status meant that he could only work in the US for two days a week, felt threatened by Rattigan's increase in power and got the board to sack him[7], even though Rattigan's cost-cutting programme had been credited with turning around Commodore's fortunes following its significant losses in 1985 and '86, which had left it with debts of $100 million in May 1987.

In public however it was being said that the sacking of Rattigan, together with another five top executives, was down to the company's sales not growing fast enough, as well as delays in introducing and distributing new models of the Amiga.

Gould, who had installed himself as interim chief executive (whilst still remaining chairman of the board), said of the sackings, with a nod to the comparative popularity of the Amiga in the UK and Germany, that:

"I am confident that these actions will improve operating efficiency and provide important momentum for our U.S. business to complement the continued strong performance of our European operations"[8].

The management sackings were not the only blood-letting at Commodore, as they were also accompanied by the sacking of 50 staff at the company's head office in West Chester, Pennsylvania[9].

Rattigan, meanwhile, was suing Commodore for around $9 million with a claim that the company had "prevented him from doing his designated work"[10], including a reduction in responsibility and authority and Commodore hiring and firing senior management without his approval.

The animosity ramped up in July when Commodore filed a $24 million counter-suit, claiming that Rattigan - who was widely credited with Commodore's recent financial recovery - had resigned of his own accord and would have been fired anyway[11].

Ranger rumours

All Amigas up to the A500 had used Motorola's 68000 CPU, although there had been rumours of a 68020 CPU appearing in the A2500 "Ranger" Amiga, launched at November 1986's Comdex Fall show in Las Vegas.

This didn't happen, but San Diego-based CSA did announce a 68020-based add on module which, with 512K of extra memory added, ran 280% faster than the standard Amiga it was attached to.

It could generate a Mandelbrot image in three minutes, which compared against the 50 minutes for a standard Amiga or the 24 hours a standard IBM PC would take[12].

Commodore did however end up showing a 68030 version of the Amiga - as a powerful engineering workstation able to run Unix - in early 1988[13].

The Ranger had been subject to rumour for a while, however Clive Smith of Commodore US was trying to dampen interest by suggesting that:

"I'm not even sure Commodore will be at Comdex. We don't comment on un-announced machines. I have read the rumours about it as well but I cannot say anything. The Amiga was always intended to be a family machine, so there will be more appearing in the future".

Commodore UK's Chris Kaday was a bit more hopeful that the parent company would throw him something, saying:

"In the UK, we'll take anything that they make in the States, but I don't know of anything at the moment. As far as we're concerned there will be no new Amigas this side of Christmas"[14].

Meanwhile, Commodore was expanding its sponsorship program.

Having already picked up the sponsorship of Chelsea Football Club for £1.25 million, which complemented Commodore Germany's sponsorship of Bayern Munich and a similar deal with Dynamo Kiev[15], Commodore added Olympic gold medalist Tessa Sanderson to its roster in the December of 1987.

Sanderson had found herself without sponsorship for the 1988 Seoul Olympics, a situation which Commodore's then-manager and sometime marathon runner Steve Franklin thought apalling.

Commodore subsequently arranged a deal with Sanderson's manager - musician Adam Faith - to the tune of £50,000, with Faith keen to point out that "the deal was not only important for Sanderson but for all other athletes seeking sponsorship". As Popular Computing Weekly's editor John Brissenden pointed out:

"For years the tobacco barons have seen sports sponsorship as a lucrative way of advertising their products. If it is good enough for them, surely it is time multi-national companies like Commodore and Atari got in on the action"[16].

At the press conference announcing the deal, Sanderson was joined by fellow Olympic athlete Sebastian Coe, as well as Faith and Commodore's Steve Franklin.

The deal followed a few months after Commodore had been rumoured to be in the running for the gig to sponsor the entire Football League, which eventually went to Barclays (or Boerclays as it was sometimes referred to by the student anti-Apartheid movement at the time[17]), although the company was also planning to sponsor the break-away "Full Members' Cup" - a competition involving all the English clubs that had been banned from Europe following the Heysel stadium disaster[18].

By the late summer of 1987, Irving Gould's boardroom blood-letting earlier in the year seemed to pay off as Commodore announced improved figures for the last quarter of its 1987 financial year.

The company had turned a 1986 loss of $127.9 million into a net profit of $28.6 million (£68 million in 2026) - despite lower turnover which was down to $806 million from $889 million the previous year. Gould commented, apparently without irony given the previous sackings, that:

"We achieved this profitability through operating efficiencies implemented without sacrifice to aggressive new product development and marketing"[19].

On its release, the Amiga 500 retailed for £500 - about £1,890 in 2026 terms, but was down to £400 (£1,510) by the summer of 1988.

Commodore had been denying the rumours of a price cut for ages, but it came at a time when Atari had moved the price of its rival ST to a very similar level, although according to Personal Computer World Atari had the advantage of "a whole lot of software, some of which is pretty good"

Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World, perhaps encapsulating the real reason that the IBM PC ended up brushing aside everything else, reckoned that:

"both the ST and the Amiga are more powerful, more modern designs than the PC or any of its clones, but there is a vast amount of software for the PC"

Kewney also included Acorn's ARM-based Archimedes in the list of alternatives, suggesting that buyers who couldn't decide between an Amiga or an ST should at least get a demo of the Acorn machine. He continued:

"You may find many good reasons not to buy an Archie, but you really don't want to see one for the first time after spending your cash on something else"[20].

The Amiga does Air Traffic

Even though Commodore's first microcomputers were all business machines, its success with its home computers of the 1980s - the VIC-20 and Commodore 64 in particular - produced a legacy which the Amiga sometimes struggled with, as appeared to be the case when a newspaper reported the use of the Amiga at the UK's Civil Aviation Authority as "ATC staff use games machines".

In reality, the CAA and touch-screen company High Tension had set up an Air Traffic Controller training system using a network of Amigas fitted with high-resolution touch screens and software written by the CAA itself.

The system, based initially on Manchester Airport, was being viewed as a possible replacement for at least some parts of the CAA's current air traffic control system.

Unfortunately for Commodore, both it and the CAA appeared to be under some sort of press embargo and so couldn't talk too much about their new system.

This appeared to be because the usual supplier of aviation simulators - Redifussion - had tendered for the training system but had not won, thanks to its price.

A miffed Redifussion announced that the CAA had dropped the whole project, which left the CAA feeling like it couldn't talk about anything until it could be proved to actually work, at least according to Kewney of Personal Computer World.

A CAA official stated:

"I can understand that one may be a little bitter about not gaining a contract like this, and I think the fact that we [the CAA] ended up giving the contract to our own evaluation unit, which wrote the software, made us a little more sensitive than we might have been"[21].

Andy Warhol and the Amiga

Recreation of Andy Warhol’s Amiga, based on original objects found in the The Andy Warhol Museum’s archives. © The Warhol https://www.warhol.org/, used under fair/educational use

In April 2014, a stash of previously-unknown Andy Warhol digital artwork was rescued from a set of old Amiga floppy disks.

Warhol had been commissioned by Commodore in 1985 to produce some art to help promote the platform and had been given an Amiga 1000 together with a whole collection of peripherals.

Of the images created, only one of Blondie's Debbie Harry was used in the promotion, and the rest were consigned to oblivion for nearly 30 years[22].

Warhol and Debbie Harry had both made an appearance at the Amiga's launch party in New York.

Date created: 28 January 2024

Last updated: 28 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.