Commodore Advert - July 1985

From Sunday Times

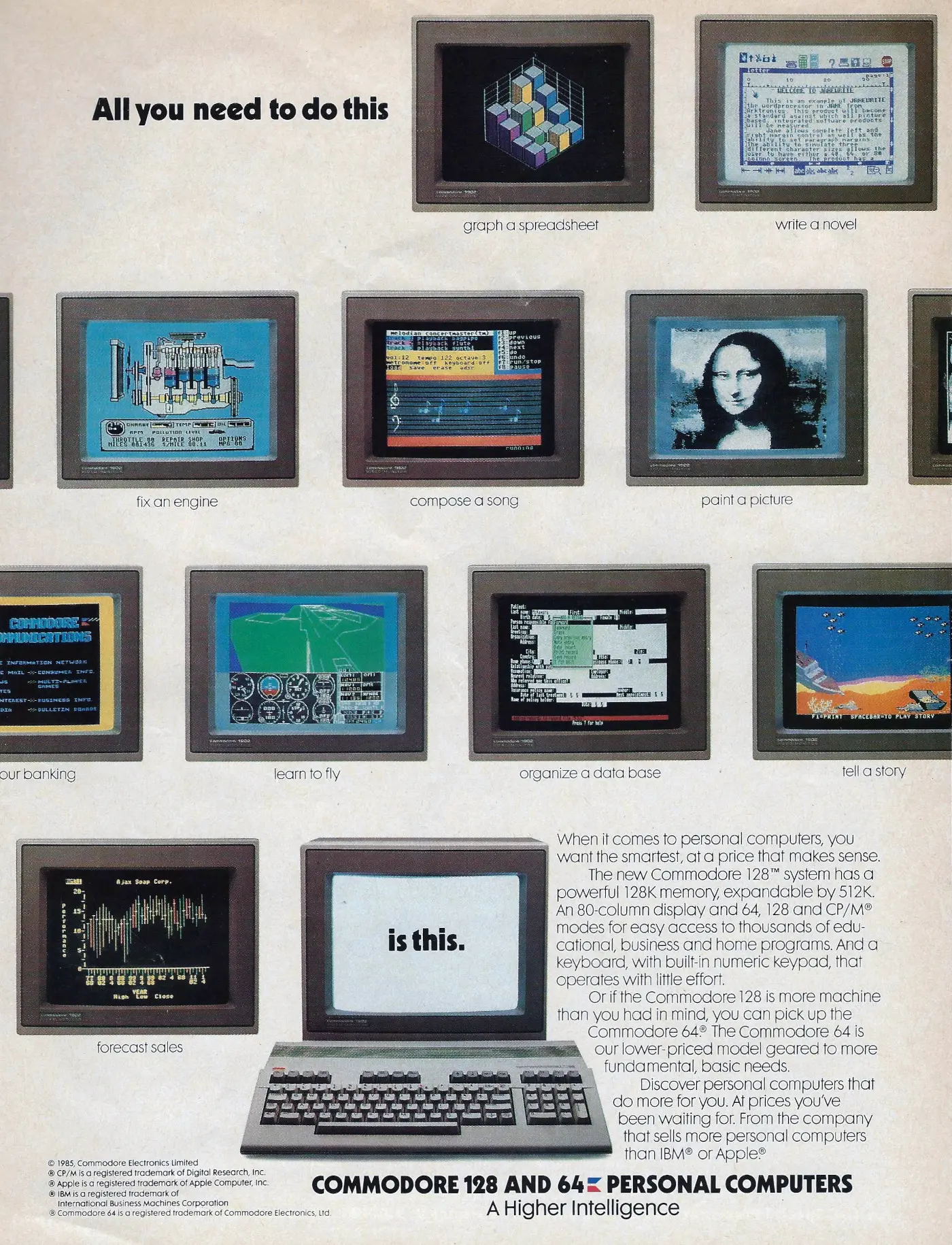

All you need to do this, is this: The Commodore 128 and 64

Officially launched at the 1985 January Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas and built with the same case used for the late-model C64s, the Commodore 128 was the company's last 8-bit computer.

Even though there had been many machines around for several years that had multiple processors, the C128 was considered as the first mass-market multi-processor computer[1], as it employed an 8502 (a 6502 derivative) for C128 and emulated C64 modes, and a Zilog Z80 for business-friendly CP/M mode.

It did have some impressive specs, and the screenshots in this advert show a level of graphics that didn't appear in IBM PCs until several years later.

Meanwhile, the C64 itself, which remains the world's best-selling 8-bit computer with between 15 and 22 million units sold, has been completely relegated to being a "fundamental, basic" product.

At about the same time as the launch, Commodore UK had appointed a new marketing manager in the shape of David Gerrard.

Gerrard was formerly from Plessey and also Texas Instruments UK, where he had been marketing TI's calculators and watches in competition with Commodore.

The vacancy had come about as Kit Spencer, under whose marketing reign Commodore had come to capture up to 80% of the UK business market, had been moved first to Switzerland and then to the US to head marketing operations there.

It had long been a source of embarassment that prior to the launch of the VIC-20, Commodore UK had been making more money than Commodore US.

Gerrard didn't seem to hang around long - as part of Commodore's "turnstile" turnover of top management in vogue at the time he was replaced in May 1985 by existing UK sales manager Paul Welch, who took on both the sales and marketing functions.

Some of Commodore's financial issues at the time could be blamed on its over-stocking situation, which seemed worse than most: in early 1985 it was announced that the company had $450 million's worth of stock at the end of 1984, whilst its long-term debt was up to $147.3 million.

It was said to be so badly overstocked that it was giving away micros, including two machines sent to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher - the one- and two-millionth machines to roll off the Corby assembly lines.

Thatcher didn't appear to be that impressed as she immediately passed the machines on to the local Pope John School[2].

Corby itself was in the news in January when 100 staff were axed, reducing headcount to 600, thanks to a drop in demand after Christmas. Commodore's general manager Howard Stanworth stated:

"The home computer market as always been highly seasonal. This year the trend has been even more pronounced than usual, and consequently it has been necessary to trim the level of permanent staff for the timebeing"[3].

Nick Bessey, Commodore's new general manager. From Popular Computing Weekly May 1985The newly-promoted Welch reported to the enigmatic Nick Bessey, from whom not much had been heard since his own appointment as general manager in around April of 1985.

Upon taking up the new role, Welch said "Obviously there are a number of marketing and sales issues that need to be addressed immediately".

This was thought to be in reference to a concern within Commodore that retailers weren't replenishing stocks until they could unload machines they already had, a problem compounded by ongoing rumours that the 64 was about to be dropped in favour of the new 128. Welch continued:

"The first of these is to implement new marketing programmes for our current range of home computer products which will ease the current over-stocking problem faced by the trade and generate the kind of demand that damaging price cuts have failed to achieve"[4].

Bessey had replaced Howard Stanworth, who was thought to have been fired after instigating a unilateral price cut on the Plus/4.

A few weeks after assuming his post, he was interviewed by Popular Computing Weekly and mentioned that he was "about the only person in Commodore who has never met Jack Tramiel", largely on account of the fact that Tramiel had left Commodore at the beginning of the year, following a bust-up with long-term financier Irving Gould.

Bessey considered this an advantage as it removed him from "the personality cult that surrounds Tramiel" - Commodore's European software manager Gail Wellington went as far as to suggest that Tramiel's leaving of Commodore and takeover of Atari was "Like one's parents getting divorced".

Bessey was clear that Commodore had issues to sort out, saying "Our challenge now is to formulate a marketing programme, which gets all the products readily available in spite of the mutually-exclusive split in the computer market between consumer and business systems".

He continued with a dig at rivals Atari, saying "I think discussion about Atari are irrelevant. The new Atari products are relatively limited - from a programming point of view".

Commodore might have had a large range of machines with which to take on the competition - everything from the cheapo entry-level C16 up to the Unix-compatible 900 machine and a couple of IBM-compatibles - however Popular Computing Weekly also suggested that Commodore's vast range of machines - said to be the largest of any micro manufacturer - just meant it couldn't adapt quickly enough[5].

Bessey spoke up again later in May when he defended the company over its lack of price cuts on the 64, despite dramatically culling the price of the Plus/4, saying "We will not be cutting the price of the 64 within Commodore. The product should be sold at around £200 and I believe it can justify that price".

The response came about following rumours that Boots and Laskys were considering dropping the 64 because of the current price war, which Commodore was a major part of. Bessey seemed to recognise that Commodore had some dealer issues to sort out, as he continued:

"I see the Commodore 64 as being our major product at least until 1986, but I have sympathy with the retailers' position - if I were in their place I would be concerned about Commodore's marketing programmes. We urgently need to work with the High Street, and will shortly be showing them our marketing plans for the year".

There was also a nod towards the failing of the Plus/4, which had recently had its price halved from £300 to £150, which some thought made the 64 look like a bad buy. Bessey acknowledged that:

"The market has not been enthusiastic about the Plus/4. I don't see the machine as being a major theme of Commodore's, although we want to continue software support. [It] could do with an improvement in the ROM - having done that we will reconsider its position. Last year it was felt that bundled software would be a hit, but what has been shown is that people are more concerned with compatibility"[6].

Bessey took up this theme again when he was picked by Personal Computing Today to be its "industry figurehead of the month", where someone of note in the business had to opine on how to improve the industry, or how the industry could survive.

Bessey wrote in a short piece entitled "The challenge facing home-computer manufacturers and retailers", and clearly hinting at the rationale behind the Commodore 128, that:

"Millions of home computers have been sold - but now research shows that there is a demand for better functionality in terms of hardware and software. The lesson we heave learned at Commodore - which applies to every manufacturer - is that if we are to enjoy the continued support of the consumer, we most provide highly compatible computers, and give the consumer real reasons to buy our products. This year's panic price cuts did nothing to generate customer confidence, and there is now a need for far greater responsibility and maturity from the people who make and the people who sell micros. At Commodore we know that, unless we deliver the highest degree of compatibility and long-term support, the consumer will go elsewhere."[7].

By the late summer, management of Commodore UK seemed to be in chaos, as Guy Kewney wrote in the August 1986 edition of Personal Computer World "who can pretend to be surprised at the decision to take the warehouse away from British management?", referring to the closing of the Corby manufacturing and warehouse site.

It was pointed out that everywhere else in the world Commodore seemed to be supplying its customers on time - although that was thanks in part to overstocking.

However, that contrasted with the UK where Commodore had managed to move only 1,000 of its new wonder-machine, the Amiga, in its first month of sales, despite the "rave reviews and pent-up demand".

A recently-exited Commodore executive was said to have reported on the "UK company's triumph in losing more dealers than Apricot, and launching the Amiga at something like 40% above what international management recommended"[8].

Meanwhile, the advert also makes note of the fact that Commodore was selling more units than either Apple or IBM - a statement borne out by Ars Technica's review of the 1980s micro industry.

This showed that the IBM PC didn't pass 50% market share until 1986[9] - but despite the sale-figures bravado, Commodore was feeling financial pressure.

At the beginning of the year, Commodore UK's managing director John Baxter had been claiming that it was matching Sinclair computer for computer and that it was heavily outselling it in terms of money.

However, a report published by Market Assessment Publications revealed that in terms of UK home-micro market share Sinclair was well ahead with 43% of the market, with Commodore at 22% and Acorn at 10%[10].

In August 1985 it was reported that the company was about to dump £20 million (about £83 million in 2026 terms) of kit on the market at half price, although general manager Nick Bessey reckoned that Commodore could keep the price of the 64 up - the machine that, despite the launch of the 128, they were planning on keeping around through 1986[11].

Bessey was moved out to Commodore Electronics at the beginning of 1986, whilst new boy Chris Kaday, who had only been with Commodore for six months at the time, stepped up to assume the role of acting general manager[12].

As well as the stock dumping, parent company Commodore International had also reported third-quarter losses of $20 million for the period ending March 1985, when the year before it had posted profits of $36 million for the same period.

Chairman Irving Gould blamed the situation on "a price reduction in February, a reluctance of retailers to rebuild rapidly their depleted Commodore products inventory and by the general slowdown in our non-US sales".

Commodore had started 1984 "like a champion" but had ended it staggering, although it was still the world's number one home computer company.

Much of the problem was given to be Commodore's totally confused product and pricing strategy, with its introduction of the flawed C16 and Plus/4 (264) when the 128 was really the machine that commentators thought should have been released for Christmas 1984.

The 64's price should have then been dropped to occupy the slot where the VIC-20 used to be, but this did not happen, even when the other models in the range had their prices cut[13].

Commodore was also unusual in that it retained its own manufacturing facilities, such as Corby, and so was less able to respond to price pressures and diminishing margins by moving production to somewhere cheaper, for instance the Far East.

This had been identified as long ago as 1983 by the managing director of Wongs UK, part of the Wongs assembly empire that built machines on behalf of many other companies like Texas Instruments, Xerox, Acorn, Atari, Coleco, Osborne and Apple.

Raymond Yap observed:

"Commodore is a peculiar animal - it has decided to carry out its own manufacture to its own needs. This puts financial, management and planning strains on the company. It is quite an undertaking for them. Many of the other companies are getting out of that, just concentrating on the design and marketing of their product. It takes an awful lot of money to bring a new computer from the drawing board to the manufacturing stage and it is no longer true to say that there are high sales-margins on computers"[14].

The C128 was often referred to in the UK trade press as "The Shotgun", which, according to Your Computer, was on account of it being able to hit three targets at once.

It was planned to retail for $250 in the US (about £750 in 2026 UK money, although exchange rates were plummetting at the time) and launched in the UK in early summer[15].

It didn't actually ship in the UK until the end of 1985, with Commodore's marketing plans being finalised just in time for Christmas.

This involved a £450 (£1,870) bundling of the C128 with a single-sided version of the 1571 disk drive, the 1570, as the original was though to be too expensive for the home market - the 1571 cost the same as the C128 itself, at around £269[16].

In a twist designed to favour running in C128 and CP/M modes, the drive ran at 5.2KBaud apart from in 64 mode, where it ran at a pedestrian tape-equalling 300 Baud.

Commodore's latest marketing manager, Chris Kaday, explained of the bundling that:

"It is our belief that home computers still sold in 'splendid isolation' are doomed from the outset. When people open their presents at Christmas they expect to have everything they need to use them straight away"[17].

No doubt the presence of Amstrad's 6128, which came with a floppy drive and a monitor for less than the C128, did something to encourage Commodore's strategy.

Date created: 06 October 2019

Last updated: 28 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.