Commodore Advert - December 1985

From Commodore Computing International

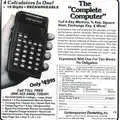

£79.99 all in: the Commodore Communications Modem

Way before the masses discovered the joys of the Internet (as in after 1995), there existed a vibrant dial-up community using Bulletin Boards and infotext/Viewdata services like Prestel.

Commodore had been one of the first companies to make a major push in to telecommunications "for the masses" and had been selling modems for the VIC-20 and the C64 for a while - at one point this apparently made the largest network of computers of a single type anywhere[1].

Several networks are mentioned in this advert: Micronet, Prestel - the UK Viewdata service running on 1200/75 baud connections - and Blaise, as well as the existence of multi-user online gaming in the form of Multi-user Dungeons-and-Dragons, or MUD.

The Communictations Modem retailed for £79.99, or about £330 in 2026 terms.

Also available in black: an advert for the Communications Modem from the previous year, when the modem was slightly more expensive at £99.99 - about £430 in 2026 - but still included the same free £30 Compunet subscription. From Practical Computing, November 1984

Commodore had got in to some trouble the previous year when it started selling its modem, by seemingly "jumping the gun" on strict conditions which required British Approvals Board for Telecommunications (BABT) approval before anything could be connected to the public phone network.

Commodore - holder of the Royal Warrant - claimed that it already had approval but that the reason it was selling modems without the necessary "green blob" on them was because the stickers hadn't been printed yet.

John Ververs, director of BABT pointed out that "it is an offence for a manufacturer to sell a modem that does not comply with the marking orders. It is also an offence to advertise a modem unless it carries a certain form of words".

Personal Computer News investigations revealed that the approval number given to it by John Collins, who was in charge of the modem project at Commodore, was a DTI reference number supplied "in the last couple of weeks", and not in September 1983 as claimed by Commodore.[2].

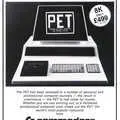

Meanwhile, Commodore's own Compunet dial-up service - launched as a joint venture with ADP Network Services[3] - went live at the end of 1984. It was also a Viewdata-based service, using the same Frame structure as Prestel and the like.

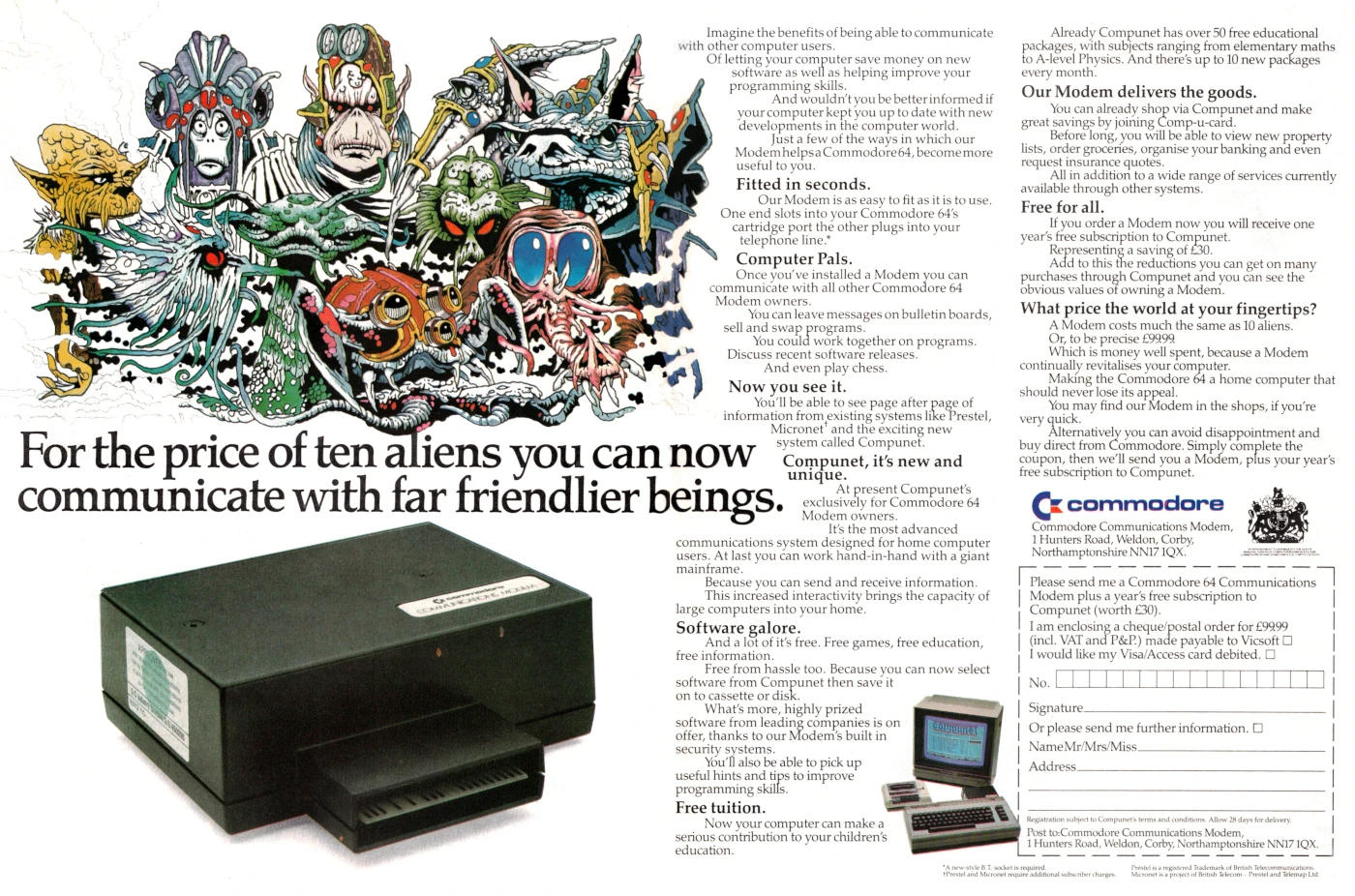

Screenshots from the Compunet service showing the main menus, the Courier messaging service, and The Jungle - a user-generated content area. From Personal Computer World December 1984

As well as MUD, Commodore's system also provided public and private messaging and a classified adverts section. Pricing for the system was, however, said to be "complex".

Software was easy enough, as the price was quoted up-front. Connection charges were more complicated, ranging from free at night to £7 per hour (£30 in 2026) during the day, with an extra £2.50 surcharge if you fancied going to 1200/1200 baud, whilst some lucky users could get special local-rate access at only 40p per hour.

The cost for leaving a message was 1p per frame per day, and anything sold privately cost 40% to 50% of the asking price.

As Commodore Horizons pointed out: "Commodore intends to make money out of [Compunet], and we all know the level of turnover the company is used to"[4].

A brief history of MUD

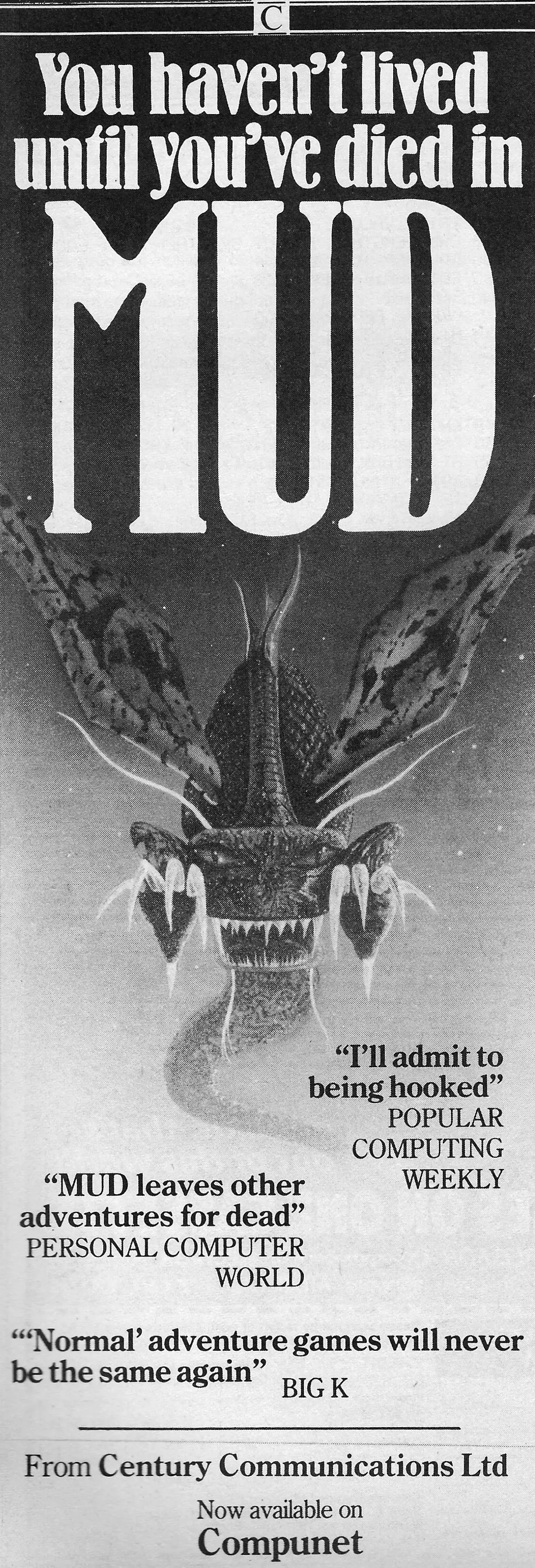

Advert for the launch of MUD, © Popular Computing Weekly, 6th December 1984MUD, recognised as the world's oldest "virtual world"[5], had first been developed at the University of Essex in the late 1970s by Roy Trubshaw.

It came from an idea that occured after meeting Richard Bartle, who had ended up at Essex University after his lower-than-expected A-Level grades meant that he couldn't go to his first choice of Exeter.

The two had a mutual interest in D&D, whilst Bartle was particularly interested in setting up a multi-user game, so the idea was born and Trubshaw started development, with software contributions from Brian Roberts and extensive testing provided by Nigel Roberts.

Bartle and Roberts, along with Trubshaw, had honourary headstones in the "graveyard", the place in the game where most novice players ended up getting lost.

The game was set in The Land - a virtual realm consisting of around 330 areas known as "rooms", even though these could be outside and exist as a kind of "mappable wilderness".

As Bartle said in an interview with Popular Computing Weekly in August 1984:

"Roy wrote and designed the core of the game - it took up most of his third year and ruined his degree. After he'd graduated - just - I took over the game's development"[6].

Bartle has been playing Dungeons and Dragons since the mid 1970s. The sword-and-sourcery role-playing game had already given rise to the computer-based Adventure game, written in Fortran by Crowther and Woods and launched on a DEC PDP-11 at Stanford in 1976.

It was followed in 1978 by Dungeon, apocryphally written by four members of MIT's Programming Technology Division in only four days, and then Zork - a watered-down version of Dungeon, with an even-more-watered down version being released for microcomputers[7].

Although not multi-player in the way MUD was, Bartle nevertheless used to connect across the Atlantic to MIT's AI labs to play the game, via EPSS and ARPANet[8] - the fore-runner of the Internet.

Meanwhile, the genre was exploding and by early 1982, Practical Computing had published a list of some 90 Adventure-like games for various micros, including - somewhat challengingly, given its 1K memory - the Sinclair ZX80.

Written on a DEC PDP-10 in 1979, initially in MACRO-10 machine code[9], MUD was at first only available to members of the university's computing society, plus a few external users - mostly students from the US - that had access to a Packet Switching Service connection.

Eventually, there were too many external users for the time-sharing system to cope with, but with unexpected agreement from the University, access to the game was moved to nighttime, which meant regular users wouldn't be disturbed and all lines into the mainframe could be used.

When Bartle completed his degree course, he "didn't like the look of the outside world" so stayed on to do a PhD in Artificial Intelligence, after which he was offered a lectureship at Essex which meant he could tend to the game indefinitely.

By the late summer of 1984, by which time it had been officially running for four years, about two or three thousand people had played the game, of which only 44 had made it to the top rank of Wizard or Witch.

Numbers were still limited as the computer itself could only support 36 simultaneous connections, of which only six could be external.

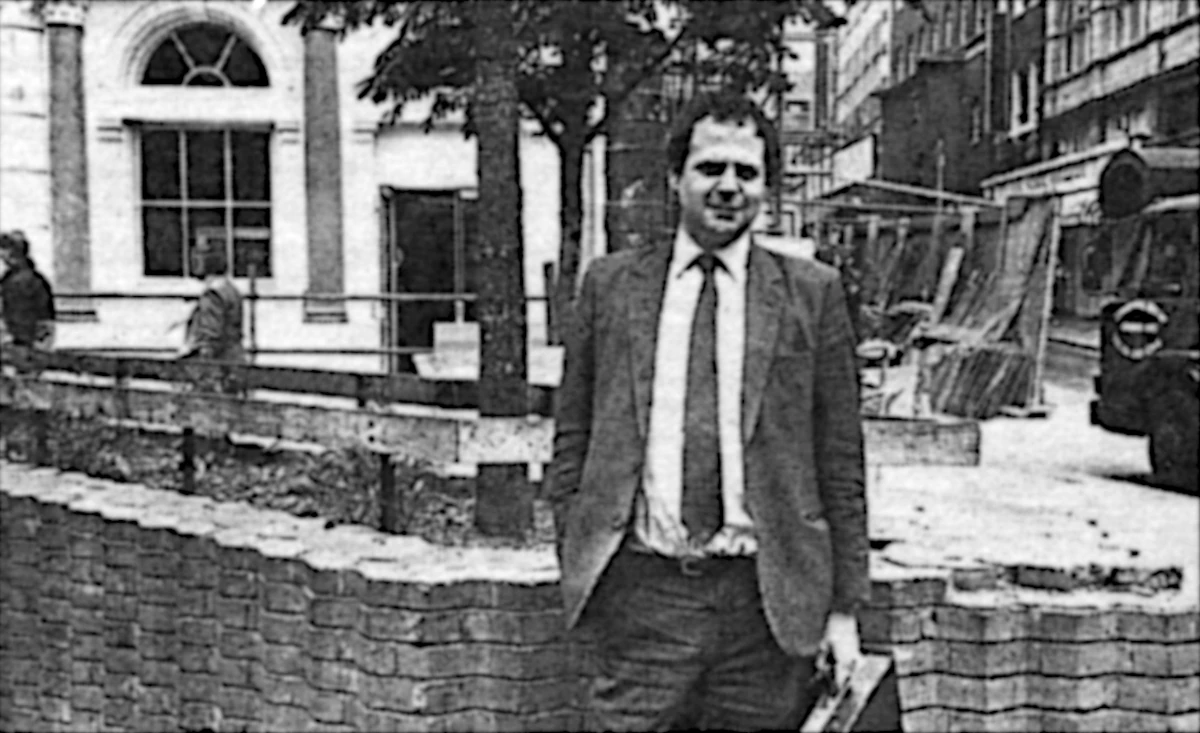

Simon Dally, formerly of Century Communications and now managing director of Multi User Entertainment. From Popular Computing Weekly, 23rd May 1985.

The game's real explosion of popularity was largely down to Simon Dally, who had been a senior editor of computer books for Century Communications.

He saw the potential and negotiated a deal on behalf of Century which saw Dally plus the programmers set up Multi User Entertainment, a company intended to develop and promote games like MUD, with Bartle and Trubshaw as directors and Dally as MD.

Dally said in a 1985 interview with Popular Computing Weekly that he "had no idea MUD would attract as much publicity as it did last year - I hadn't even played it when I signed up Richard Bartle". He continued:

"It dawned on me that the only way to get MUD off the ground was to create a company for it. Century did a lot to help set [it] up and are shareholders along with myself, Richard and Roy"[10].

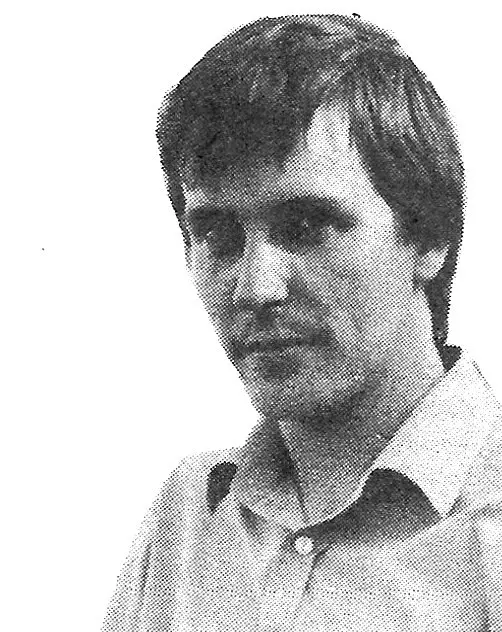

Richard Bartle, © Popular Computing Weekly, August 1984The pair went on to develop MUD 2, which Dally suggested would "amaze the world".

MUD 2 was a new version commissioned by UK telecomms incumbent British Telecom (BT) in 1985 and which launched at the Personal Computer World Show in September.

It ran on a VAX 11/750 and initially had 36 telephone lines available to it, but it had an option for up to 100 incoming lines at a later stage if there was enough demand.

The game could support a maximum of 100 players at the same time in around 1,000 rooms, whilst the original version provided less than 400.

It cost £20 up front (£83 in 2026) to join, which bought a "MUD Pack" including registration fee, instructions, a map of the game and 30 credits, each of which lasted for 6 minutes, meaning that it cost £2 per hour (plus phone charges) to play, although it was still only available at nights and weekends.

Mike Anderies of BT said "Our intention is to make MUD 2 as cheap as possible" with BT intending to put the game on computers across the country if it proved successful[11].

Meanwhile, the original MUD, which was still running on the University of Essex's mainframe, was made available on Commodore's own Compunet.

Just a week after BT had announced its own major promotional campaign for MUD 2, Commodore announced that it was opening up its original version of MUD to non-Commodore 64 owners in August, putting it in direct competition with the former state monopoly.

Compunet also announced new charges for its MUD, ranging from a monthly subscription of £5 plus £2.50 per hour, or £25 (£100!) per month and £1.75 per hour.

Compunet's Alan Carmichael said "The hourly rate includes all network charges - and because Compunet already has access points across the UK, the phone bills are cheaper too"[12].

Compunet didn't stop at MUD, as by April of the following year it announced the development of a new multi-user space-trading and travelling game, provisionally called Federation II, which was set to be previewed at the forthcoming Commodore show in May 1986[13].

Compunet moves mainframes

Micronet's MUD was not the only thing to move systems, as Compunet itself also moved machines on the 1st of July 1987, when it de-camped to a new mainframe with data based on a week-old backup from the old system.

The new setup was written in C and ran on a bunch of 68020 processors, each of which was dedicated to a specific task, leading to a much-improved service which Compunet described as being a "multi-task, multi-threaded software design, having a VME architecture".

Another spin-off of the new design was that it became much easier to support new micros in addition to the existing Commodore 64, a change which Popular Computing Weekly suggested would "move Compunet from being a hugely-popular network for Commodore 64 owners to being a real force in the world of micro databases"[14].

There's no mention of it here, but presumably MUD or BT had licenced the name "Dungeons and Dragons" from trademark-holder TSR, as TSR had been famous for taking action against the proliferation of unlicensed computer software based upon board games occuring since the latter half of 1982.

Conversion of board game to computer game was considered easy, and software companies had been cashing in on the fact that the name of the game was already well established.

TSR Hobbies, owner of D&D was not impressed with this and had taken out a full-page advert warning people against producing knock-off versions of its games, saying that "action will be taken" against "anyone using or intending to use any or all of TSR's trademarks", at a time when only Mattel held an official licence to produce games featuring the name D&D.

TSR general manager Tom Kirby said that "We have had sufficient troubles now to justify placing the advertisement - but so far most of the actions we have had to take have arisen as a result of ignorance by the infringing party".

Waddingtons - owners of Monopoly - was having similar problems and it had no plans whatsoever to licence its games - managing director Andrew Lauder was on the record as saying that he considered video games as "anti social".

Unfortunately for Waddingtons, a Californian appeals court had already ruled that the name "Monopoly" had become too "commonplace" to be afforded protection under trademark law, although the Supreme Court was the deciding whether to overthrow that particular decision[15].

Almost exactly a year later, Waddingtons, which had generally seen micros as an all-out threat to its board-game business, had capitulated and had signed up with Leisure Genius, although - as Leisure's managing director Peter Deutsch indicated - that initial deal was "based on [Waddington's] new range of pre-school educational toys"[16] and not the prized board game.

Games on Micronet

Back in 1985, also accessible using the Compunet Modem, was Micronet - the 30,000-page micro-focused part of BT's Prestel service which was a joint venture between BT, EMAP and Canada's Tele-Direct[17] - which had become available to Commodore users the previous year when a dedicated 64 database launched in August 1984.

This required the addition of a Micronet Modem Communication Cartridge for £43 + VAT (about £210 in 2026 money), but gave users 24-hour access to downloadable software, some of which was free.

In addition, several big software companies of the day, like Anirog and Llamasoft, were offering 20% discounts. Also available were things like bulletin boards and several precursors to more modern features like news feeds, a home-education service, "armchair shopping" and the massively-parallel interactive strategy game "Starnet".

Starnet, a space-war variant which could be played by up to 500 users at a time, finally launched on Micronet at the very end of 1985, around two years after it had first been announced.

The original version, as written by Mike Singleton - author of Lords of Midnight and Doomdark's Revenge - had been ready fairly soon after the announcement, however it was closed and the software was re-written by Micronet member Lawrence Kirby.

Despite the two-year delay, Starnet still managed to beat rival multi-user game MUD, by then owned by BT, to the drop by a few weeks[18].

The cost of Micronet was abour £1 per week, plus 38p (about £1.10/hr in 2013) per hour (evenings and weekends) for the on-line charge[19].

In 2012, average internet use in the UK was 16.8 hours per week[20], which meant Micronet would have cost nearly £1,000 per year in phone calls alone if the 1980s model of time-based charges was still in use.

Micronet went on to launch its own version of MUD, called Shades, in the late summer of 1986.

It had been having problems finding a system that could both handle a large number of users as well as support the Viewdata format, but the issues were overcome when Micronet's technical director Mike Brown developed a Viewdata-to-ASCII gateway which connected via Prestel, enabling the use of cheaper local-rate telephone numbers.

These routed through to the Shades system in East Grinstead, West Sussex, whilst retaining support for all the positive features of Viewdata, including colour[21].

It was also relatively cheap, costing "only" 97p (£3) per hour with no registration or monthly subscription fees, apart from an existing Micronet subscription[22], although there was also occasional special offers such as a free five-hour play for existing Micronet members offered in July 1987[23].

When Shades became the first Micronet-to-ASCII service gateway earlier in 1987, it meant that users on the 1200/75 Viewdata standard could now access other non-Viewdata plaintext services.

The service was successful enough that Micronet opened up an additional gateway to Telecom Gold - BT's email service - in July 1987, with a full support service and a name of Interlink.

The service ran over an X25 gateway and gave access for Micronet's 20,000 subscribers to the 70,000 Telecom Gold users (about the same as Prestel's claimed 70,000 subscribers) plus "tens of thousands of foreign Dialcom-affiliated Email networks[24].

Telecom Gold, later known as BT Gold, ran on Prime minicomputers[25] and had been an early provider of email services when it was launched in 1982.

Although it was nominally global, most of its user base was concentrated around London where, as if to prove once more the direct lineage between early chat systems and CB radio, many of its users would meet up for "eyeballs"[26] in the actual real world.

War Games and the rise of hacking

Over in the US, by the spring of 1986, it was estimated that 25% of all computer owners possessed a modem.

CompuServe was the largest information network at the time, with 200,000 subscribers and its "electronic parties" (chat rooms) were becoming popular.

Although in the US phone calls to local-area access numbers would have been "free", the networks still charged per-hour access, with an hour on CompuServe costing $6 off-peak.

However, there was already a huge amount of data available, such as Grolier's entire Academic American Encyclopaedia, which weighed in at 21 volumes in its print version.

E-mail was also well established, as was the darker side of the on-line world.

Back in 1983, three New York schoolchildren hacked in to Pepsi Cola and got control of its Canadian freight operation, placing large orders from fake companies and delivering empty bottles to Pepsi subsidiaries all over Canada.

Although the hack cost Pepsi "a fortune", the trio - which was tracked down by the California police and the FBI - escaped prosecution on account of being minors[27].

Only a couple of months later, the FBI raided the homes of more than twelve teenage "computer enthusiasts" in connection with hacks in to the Telenet system, which linked 1,200 commercial computers across the US.

In what was said to be a "War Games comes true" moment, the teenagers, from New York, LA, Detroit and Oklahoma, had hacked in to computers at Los Alamos - home of the Atom bomb - and McClellan Air Force Base in California, causing "thousands of dollars" in damage by changing or deleting information[28].

The Lovell Radio Telescope, a.k.a. Jodrell Bank, near Goostrey in Cheshire, 1985By 1985, hacking had moved in to space when a group of New Jersey teenagers was arrested for actually hacking in to some communications satellites and shifting their orbits[29] and by 1987 the infamous Chaos Computer Club, based in Hamburg, was active.

Six West German hackers allied to the CCC had claimed to have found a flaw in the VMS operating system popular on VAX computers, which were widely used in research and academia.

The group then used a password-stealing Trojan Horse to hack in to more than 100 VAX machines on the US Space Physics Analysis Network (SPAN) and reckoned that they had access to almost everything connected to SPAN.

That was thought to include at least 1,500 VAX minis as well as other networks like that of CERN, the UK's Starlink astronomy network and even Jodrell Bank, the famous radio telescope at Goostrey in Cheshire[30].

Even before the internet, it was already becoming clear that the more connected computers became, the more vulnerable they could be, with the problem being significant enough that by 1987 the Metropolitan Police in London had set up a dedicated Computer Crime unit, headed up by Detective Inspector John Austen.

Armed with the Forgery and Counterfeiting Act of 1981 - the same which was used in the prosecution of the Prestel hackers Schifreen and Gold in 1985 - Austen would go after hackers, whom he described as:

"Normal teenagers [who have] got a BBC Micro and play games on it. [They then] get bored with that and then they buy a modem and suddenly they're interested in public exchange networks and probably think they have more capability than they do".

DI Austen went on to set up a course at the National Police College so that officers from other forces could be trained, which meant that at least one police officer in every force in the country would be computer literate. As Austen said:

"All we're doing is taking experienced detectives and we're topping them up with some computer knowledge sufficient, one hopes, to be able to deal with the evidential requirements of the computer-related crime"[31].

Jeff Minter and the rise of the Llama

One problem that Commodore users who weren't using the "Micronet cartridge" faced when using Micronet was that they couldn't download software from the service using Commodore's own Compunet modem.

However, in April 1985 it was announced that Micronet had commissioned a new communications protocol, which would make enable downloading and thus make the service more attrictive to C64 owners.

In something of a "circular reference error" (to use an old spreadsheet phrase), the software that would let Commodore users download software from Micronet was available on, er, Micronet.

Perhaps these problems helped explain why it was said in the summer of 1986 that only a small percentage of Commodore 64 users still had access to Compunet or had even seen it, which seemed a shame as Compunet was also considered by Popular Computing Weekly to be rare amongst UK on-line services by being largely user-content driven.

Much of this was centred around "The Jungle", which contained software, computer art, music, clubs, gossip and so on.

Even in 1986 it was possible to get picked up by major companies after posting artwork or software, as happened to Bob Stevenson and Doug Hare, both of whom ended up working with Activision.

Other famous programmers could also be found hanging out on Cnet's Party Line - a service like CompuServe's CB Simulator, similarly based closely on CB Radio and which was first demoed at the 1986 Commodore Show at the Novotel in London - like Jeff "Yak" Minter and Tony "Ratt" Crowther[32].

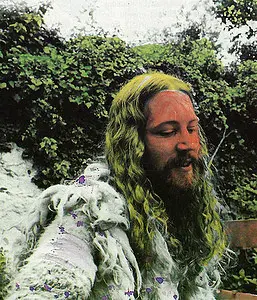

Jeff Minter, © Your Computer December 1987Jeff Minter was something of a software legend and produced a long line of software, much of which was based on or named after various ruminants, in particular Llamas.

Minter was particularly associated with Commodore, having written his first software on a PET in 1979 before buying a VIC-20 from a shop in Oxford, hours before succumbing to a virus infection.

Several months of confinement in bed followed which gave time to concentrate on programming, and he never returned to his maths and computing course.

In April 1982, Llamasoft was taking in about £15 to £20 a week in sales, but by 1983 it was banking around £5,000 a week (£22,800 in 2026) - a situation which the one-man-operation Minter described as "really nuts".

60% of this was coming from just two VIC-20 and Commodore 64 games he was selling in the US - a copy of Defender, which Minter had broken into the US market with, and Gridrunner, which became a Number 1 best-seller, having sold 15,000 copies in ROM cartridge form[33].

Minter was perhaps one of the first "celebrity" programmers, and believed that the future was "the writers [and] not the publishers".

In an interview with Popular Computing Weekly in May 1983 he said "In America it is already going that way - companies are starting to push names. [US software house] HES is now pushing me and Tom Griner who did Choplifter for the VIC. He is only 17 and is very strong on coding and does a lot of very good conversions"[34].

By 1987, Minter, whom Your Computer delightfully described as being like a "lost extra from a late sixties biker-trash California B-film whose Harley has somewhere in the time-warp transmuted itself in to an open-top Ford Escort", had earned enough to buy a farm in Wales, with an idea to rear llamas, to go with his existing cottage opposite Greenham Common and the Llamasoft HQ in Basingstoke.

By this time he seemed to have cooled off on the Amiga, which he'd been keen on the year before[35], and seemed to think that the Atari ST was where it was at, saying that it was "a happening machine" and that the ST's MIDI socket trumped the Amiga's "amazing sound chip" because real musicians could connect real gear up to it.

Minter was also clearly not a fan of the increasingly-dominating PC, suggesting that "PCs are so boring. They're dead. It's archaic technology. It would be more fun to sit outside in the garden and watch the grass grow. PCs are unbearably dull".

Having got that off his chest, the Pink Floyd-loving Minter waxed lyrical in his August 1987 interview with Your Computer about the virtues of Macchu Picchu and an old llama that lived there: "I got on with him really well. He didn't spit at me"[36].

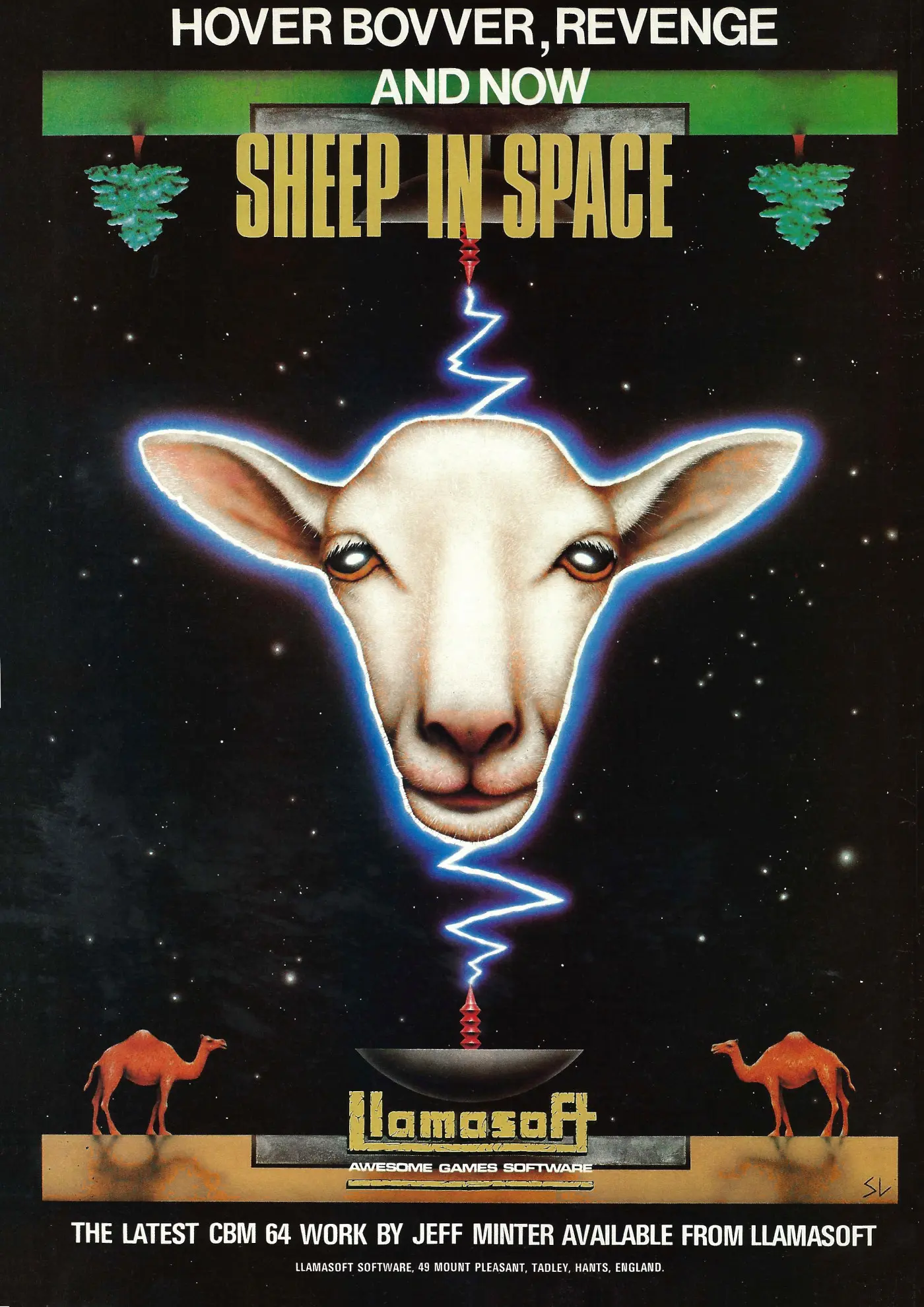

A Llamasoft advert for Minter's Sheep in Space - another ruminant-themed game - on the Commodore 64, from before the switch to Atari. From Your Computer, July 1984

By 1987, Compunet had migrated off its original DEC 10 timeshare-based mainframe onto a new one running a bunch of Motorola 68020 processors, whilst its applications software had been re-written in C - the update meant that Compunet's capacity was doubled and everything was a lot faster to use[37].

The network had also opened up a new area on its network specifically to bring freelance programmers and software houses together, in a formal recognition that Compunet had already become something of an "online job shop".

Many major software companies were already hosting directories on the system, in which they could advertise requirements.

They also had access to Compunet's Closed User Group, in which programmers could host demos of their software or computer art - many examples of which Popular Computing Weekly reckoned "would make a fine addition to a collection", with the best being uploaded by Compunet into a "demo greats" hall of fame, available in page 'DEMOH'[38].

The trend had been noticed a few months before, when Compunet's Jane Firbank pointed out to Popular Computing Weekly that "Some kids started putting up demos, graphics and so on. The software houses started to pick up on this because they're desperately short of programmers".

It was thought that software houses Mirrorsoft, Elite and Melbourne House had already recruited amateur coders as a result of Compunet exposure, whilst professionals were also using the service as a way to get work.

In something of a premonition of the whole "social-media lens" of collective Facebook or Twitter crowd-sourced wisdom, Firbank also pointed out that "because of all the communication going on on Compunet, you're not going to get anybody signing somebody up on a rip-off deal"[39].

Later in 1987 came the news that Commodore had also rented space on the ISTEL network - a Viewdata service that had originally been set up by British Leyland, before being sold to a management and employee consortium for £75 million as part of the Rover Group's restructuring plans[40].

ISTEL was one of two networks that provided dial-in access to Compunet, the other being ADP. ADP had been offering twelve dial-up nodes that were free to users within local-call access - a benefit which covered 80% of Compunet users.

However when Compunet announced that its prices were going down from 90p per hour back to its previous 60p per hour, it neglected to mention that the ADP nodes were closing down so most of its users would actually be paying more to get on-line, as they now had to go through the non-free ISTEL network[41].

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 28 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.