Commodore Advert - June 1983

From Practical Computing

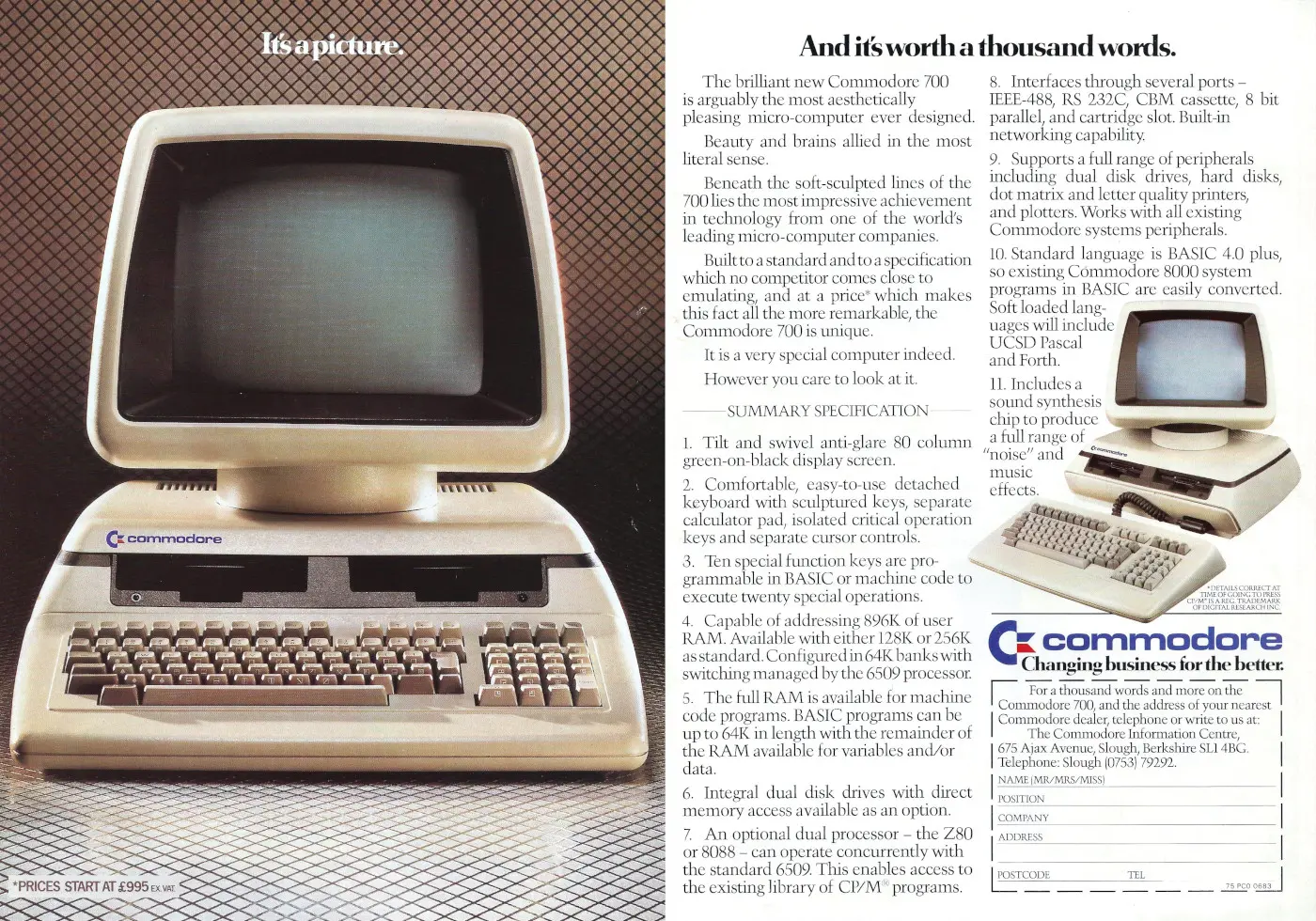

Commodore 700: It's a picture - and it's worth a thousand words

With a case popularly believed to have been designed by Ferdinand Porsche, but which was actually designed by Commodore's regular industrial designer Ira Velinsky, an on-board 6509 CPU and an option of a second processor - either a Zilog Z80 for C/PM or an Intel 8088 for MS-DOS (this was included as standard on the 720 model[1]) - the 700, known as the "B series" in the US for no particular reason other than "B" stood for "Business", certainly looked the part.

However, it had to be relaunched several times and was eventually binned in favour of the 8000 series, which which shared the same case design but had been released before it[2].

Even though it's two years into the era of the general-purpose IBM PC, it was a machine that still booted in to BASIC - a language still suitable for beginners, but which was looking a bit odd for a business machine.

The 700 - part of the CBM-II series - shipped with 128K of RAM and the 720 with 256K, but the 700 could take up to 640K externally. This, however, could only be accessed by "bank switching" - addressing individual 64K banks at a time, as 64K was the practical limit an 8-bit processor could handle, and it was a process that required special programming techniques.

The 700 also apparently had CP/M-86 compatibility with the IBM PC and, interestingly, the Sirius 1/Victor 9000[3] - the latter machine being that which Commodore PET and 6502 designer Chuck Peddle had a big hand in.

Commodore also built a "P" version of the CBM-II, also known as the 500 series and which was intended for personal or home use.

It differed from the 700 in that it used the 40-column VIC-II display chip - the same as used in the Commodore 64 - whilst its bigger sibling supported 80 columns via its use of a Motorola 6845.

Both models also contained the famous SID sound chip from the 64, however the presence of the VIC-II in the home model meant that its CPU had to run slower to match the VIC's clock speed.

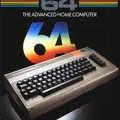

The 500/P series was never officially released in the US as the Commodore 64 was too popular and its specification was too similar, although apparently a few P500's sold in Europe.

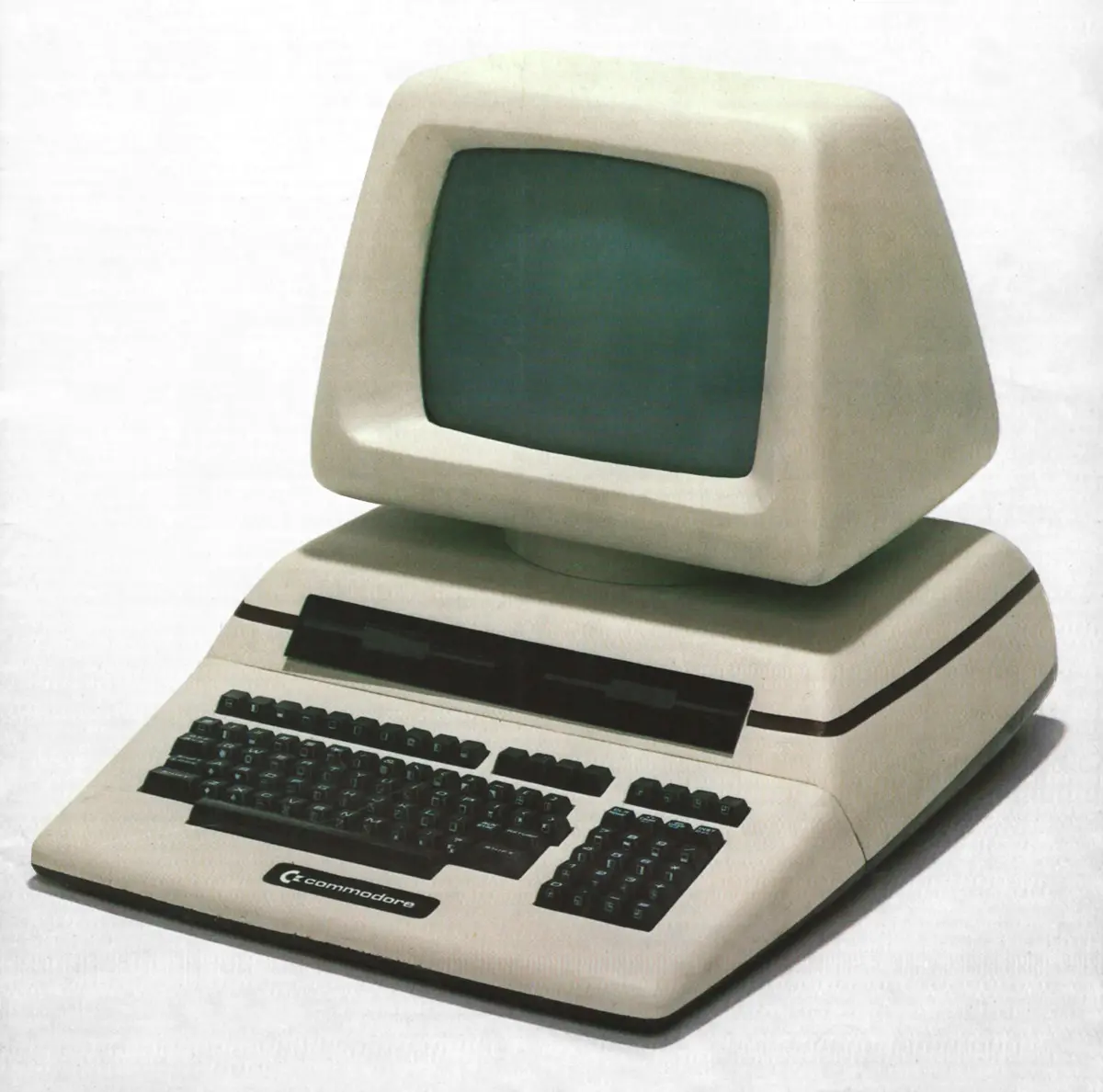

A possible prototype of either the 720, 8032SK, 8096SK or a 4032SK. Although similar to the 700 B series, it differs from any released PET of this style by not having a black bezel around the monitor, and by having a Commodore badge in front of the keyboard. From Commodore Computing International, August 1982

Increasing competition in the latter half of 1983 led to something of a price war, and Commodore was quick to cut the prices of its machines across the board.

The 700 series was clipped by 18% down to £650 (£2,960 in 2026 money), whilst the older 32K 4032 model (one of the "classic" PET models) had £200 lopped off the price, a near 30% price cut.

There was even suggestion in the trade press that price cuts were starting to make the C64 interesting as a small business machine, where a system combining the 64 with a 2MB disk unit and a decent dot-matrix printer could be had for £1,500 (£6,850)[4]. Mike Tait, Commodore's national sales manager was quoted as saying:

"With the reduced prices, Commodore is even more strongly positioned to further expand its established user base of over 110,000 business installations in the UK".

Around March 1983, the first hints started appearing of a possible move of European production and distribution from the existing Braunschweig factory in West Germany to Corby - an area of the UK with high unemployment, and thus a guaranteed supply of labour, rent-free deals and generous grants from the Department of Industry.

The logic behind this move was that the UK was already accounting for 40% of Commodore's entire European sales in home computers, so production of the VIC-20 and the 64 would move[5], giving Braunschweig four times its existing capacity to manufacture the model 500 and 700 business machines[6].

The Corby factory was expected to create 200 jobs and produce 700,000 units a year.

The announcement of Corby didn't however do much to calm the nerves of dealers, who seemed to be in a bit of a panic over the release of the software package Silicon Office for arch-rival ACT Sirius's machine.

According to Guy Kewney, writing in May 1983's Personal Computer World, this could be interpreted in the same way as seeing rats running down the anchor cable on a sinking ship.

Silicon Office had been previously only available for Commodore's 8096 and had helped drive its sales, although they still represented a small fraction of the 80,000 Commodore machines thought to be in the UK at the time.

However the news of the £900 package's availability for the MS-DOS Sirius - and by extension other similar 8088-based machines including DEC's Rainbow and hundreds of IBM clones - threatened what little sales there were for Commodore's business machines.

Things weren't helped by the fact that Commodore only just managed to show its new business machines - including the 500 and 700 models which were launched in February 1983 - at computer shows, where some dealers had to resort to showing cardboard cut-outs instead.

Of the machines that were shipped, many were faulty and their integral disk drives were missing. One dealer who had shown five of the machines at one of the larger Commodore shows had had to send them all back because they didn't work.

Guy Kewney suggested that Commodore's problems came down to the fact that the company was "drunk on VICs".

The previous year, Jack Tramiel - Commodore's founder and CEO - had forecast the end of the company's first home computer, the VIC-20, a little less than two years after its launch, suggesting that it was a "games machine" and that the Commodore 64 would swiftly replace it. Tramiel also said:

"I'm very glad we had the strength to resist the games market which Apple and Atari were getting into Space Invaders - we have developed a firm background in business software, which is where the market lies".

A year later Tramiel had somewhat changed his tune - after dicovering that his company was about to sell its millionth VIC - and called off the VIC's termination notice, with production moving away from business machines to support home micros instead.

This left dealers with 500 and 700 machines that weren't selling, whilst having to sell older 8040 and 8096s in new cases. One source within Commodore HQ at Slough, when asked what was going on, apparently said:

"Don't ask me. I'm just keeping my head down, and hoping nobody notices[7]".

In hindsight, the switch away from business towards home micros lost Commodore crucial ground that it never recovered.

Whilst the home micro market remained profitable for a few more years - especially for Commodore as it was about to release the 17-million-unit-selling Commodore 64 - the concept itself was ultimately doomed as both home and business machines would eventually become the same thing: the dull but consistent IBM PC and its clones.

Meanwhile, back in early 1983, the home computer market in the UK had reached a penetration of just under 1 million households, with the figure expected to double by the end of 1985, according to a survey commissioned by Gowling Market Services and conducted by the British Market Research Bureau.

The survey also revealed that 45% of home computer users were 18 or under and, unsurprisingly, arcade games were the most popular application, although 25% of households did use their machines for educational purposes[8].

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 10 February 2025

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.