Dell Advert - July 1987

From Personal Computer World

You'd better believe this... or you won't believe our prices

Michael Dell started out at the age of 13 selling mail-order stamps, and by the time he was at high school he was earning some $17,000 a year selling newspaper subscriptions with the aid of an Apple II.

Whilst at college, he started buying parts to upgrade older IBM PCs that dealers were desperate to get rid of and would re-build them to order, by asking customers what they wanted, phoning up a parts supplier in Dallas, flying up there to collect them and hauling the whole lot back in a car and trailer to Austin.

By the age of 19, Dell was making over $30,000 a month, at which point he dropped out of college to run his new company full time.

By 1987, at the age of 22 and only three years after starting PC's Limited, his company was turning in revenues of $70 million a year.

Compared to IBM, Apple or Compaq's revenue, this might have been small beer, but it proved that the PC market still had room for new ideas[1].

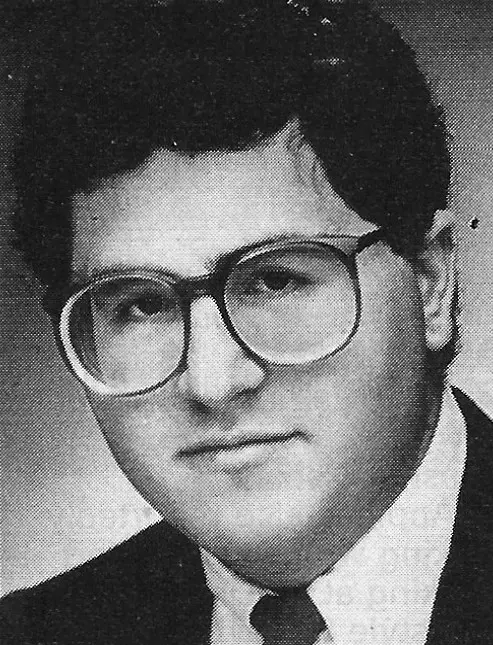

Michael Dell, © Personal Computer World, July 1987In the summer of 1987, PC's Limited launched its first international subsidiary - as Dell Computer Corporation, based in Bracknell, Berkshire in the UK, where it continued with its direct-to-consumer model.

Mail order had a spotty record in the UK, with Sinclair's infamous "28 days delivery" actually meaning "some time in the next few months" having tarnished the idea.

However, maybe its time had finally come - perhaps Dell could actually deliver when it said it could, or perhaps it was the fact that it actually offered proper professional-level on-site support, but whatever it was the company proved successful in its direct-sales approach. This was just as well as Dell PCs were only available via mail order.

Back in 1985, PC's Limited was the focus of attention at the November Comdex Show in Las Vegas as crowds flocked to see its breakthrough sub-$2,000 IBM AT clone. It was a version of this machine - the 28612 that, along with a newer 80386-based machine, that were its first PCs to launch in the UK.

Dell's 286 machine - a "fast but inexpensive AT clone available mail-order in a variety of configurations". From Personal Computer World, July 1987.

The 286 machine was reviewed in July 1987's Personal Computer World by Robert Schifreen - famously one of the two "Prestel Hackers" who - along with Stephen Gold - had been charged with breaking into Prince Philip's Prestel mailbox in 1984. He concluded of it that:

"I like this machine. It has a fast processor, with a hard disk to match. It has a higher specification than just about any other standard machine, with two serial ports and 1MB of RAM, as well as a parallel printer port and an EGA card/monitor. A complete system costs appoximately £2,400 when VAT is added. It's not cheap in the same way that an Amstrad is cheap, but if you want value then you've found it. For the money, it's unbeatable[2]."

£2,400 is about £8,800 in 2026 money.

Whilst some of its early lower-spec machines were built for it by American Research Corporation, by 1987 it was designing and building its own hardware, and became one of the first companies to release a "hybrid" machine which could support the as-yet-unreleased OS/2 - the much-delayed Microsoft operating system intended for IBM's new PS/2.

At the time it was expected that IBM's new Micro-Channel Architecture would become the next dominant hardware platform and that it was only a matter of time before official MCA-PS/2 clones came out, so machines like this were seen as a stop gap[3].

However, IBM was hoist by its own petard as the ISA market - the original IBM PC architecture that it had created - proved to be too big to usurp and MCA never really caught on.

In fact by the end of 1987, IBM's PS/2 only accounted for 38% of the company's sales and just 9% of the entire market, whilst Amstrad had even overtaken Big Blue in terms of actual units shifted, selling over 100,000 distinctly non-PS/2 or MCA machines during 1987[4].

Even by the end of 1988, the year when 386-based machines were the dominant "thing", the OS/2 user-base was still considered as "small", but it was still hoped that this would improve as more software specifically for the new operating system came to market.

It was also hoped that the falling prices for the older 286 machines - which could still run OS/2 and some of which were under the magic £1,000 barrier by the start of 1989 - would encourage take-up[5].

Wait years for a bus, then they all come at once

There was nothing particularly new about the idea of expansion buses - which were simply a way of extending the memory and input/output of the computer out into the world at large.

Architectures like S-100 and SS-50 dating from the mid-1970s had offered sometimes 20 slots of expansion, but the idea had somewhat disappeared after the Commodore PET, although Apple kept the idea going in the Apple II.

However, the re-appearance of the general-purpose bus on IBM's 5150 - the original IBM PC - was perhaps more significant than that machine's use of new-fangled 16-bit processors, because it represented an actual standard that third-parties could build against.

This became quickly entrenched, so much so that when IBM launched its improved AT bus in 1984, it essentially kept its original bus for backwards-compatibility but lashed on an extra 8-bits to support the new 16-bit architecture, and when 386's rolled around, the AT bus was still the only game in town.

However, it was getting increasing outmoded due its lack of support for 32 bits, so to address this IBM created the MCA bus for its PS/2 machines, which it unleashed in April 1987.

The Gang of Nine

MCA, which to IBM was a "technology of the future" and which came out of its centralised mainframe and minicomputer mentality[6], fixed a lot of the drawbacks of the older bus and supported 32-bit CPUs.

However it also obsoleted hundreds of manufacturers' plug-in cards overnight, and it was the weight of this legacy baggage that was perhaps too much, as towards the end of 1988 a group of clone manufacturers - led by Compaq and including HP, NEC, Wyse, Epson, Zenith and Olivetti - got together to release the "Extended Industry Standard Architecture" bus standard.

This group, known as the Gang Of Nine, provided a specification which - much like the change from the original IBM bus to AT - simply lashed some extra connectors to the old spec to ensure backwards compatibility, but which would also promise to be as good as, if not better, than IBM's MCA.

The spec was hazy, and the challenges of supporting 8-, 16- and 32-bit cards all at the same time were significant and it was considered a bit of a kludge, but the choice was now there - MCA or EISA, with the odd outlier, like Apple's NuBus[7].

Meanwhile, IBM was expecting that its move into MCA, and the fact that this time it was backed up with the power of patent and copyright law, would convince the rest of the world to upgrade with it.

So much so that IBM abandoned the traditional PC market completely, leaving it behind to what it assumed would be a rapidly-dwindling band of cut-price cloners.

This backfired somewhat as the consensus seemed to be that "the PS/2 has poor software support and is too expensive - thanks, but no thanks".

By the end of 1988, IBM seemed to have realised that the world wasn't going to switch to MCA just because it said so, and so it started licencing its new architecture to clone manufacturers such as Dell, Tandy, Apricot, Olivetti and Amstrad.

However, the bus standard was still controlled by IBM, and this time clone manufacturers had to pay for the privilege to use it - to the tune of 2-5% of sales.

And to really put the boot in, there was even a claw-back for historical "un-licenced" clone activity[8].

At about the same time as the gang of nine was doing its thing, IBM was stirring it up as it finally unveiled products that implemented one of MCA's much-vaunted features - the ability to run Bus Masters, or plug-in cards that had their own processing power but which could access stuff on the computer they were plugged in to without going via the CPU.

Although the things that IBM demoed at Comdex weren't yet production-ready, and the whole idea had taken 18 months to actually come to fruition, they did however show how the MCA bus could significantly improve performance in things like graphics cards, which no longer had to go via the CPU to move screen data around.

The bus master news conincided with some news of progress on Presentation Manager, the graphical user-interface which was part of Microsoft's OS/2 - the much-delayed operating system for the "new" machine - as it was announced that some 80 applications were now available[9].

IBM's tactical error

With IBM's realisation that things weren't going its way came a revival the old AT bus in the PS/2 Model 35 - a move intended to try and re-capture some of the market loss it was experiencing, having gone from 36% market share before the lauch of the PS/2 to around 25% by the end of 1988.

As well as that, Big Blue had also closed its PS/2 factory in Boca Raton, Florida, with both of these events seemingly to confirm the view that the company had made a tactical error by moving to a completely new architecture, rather than gradually evolving its existing one, of which there were now millions in the wild.

The very existence of the EISA consortium seemed to be itself a clear message that the cloners considered IBM's royalty and enforcement claims on MCA as "ludicrous".

Writing in Personal Computer World, Tim Bajarin reported that sources close to Compaq had even suggested that the whole reason for EISA was a way to force IBM to "get off its high horse about owning all this technology and [to] drop the royalty scheme altogether".

When the first "personal computers" had appeared in the latter half of the 1970s, IBM had dismissed them as toys, but when businesses started taking them seriously, it noticed and responded in kind when it eventually launched its "skunk works" 5150 PC.

The original business plan for the PC had suggested sales of 270,000 over the entire lifetime of the machine, so the fact that it sold that number in the first six months of launch and went on to shift around a million a year ever since was significant, although to put it in perspective those sales still only accounted for around 9% of IBM's $55 billion annual revenue, with much of the rest made up from its traditional minicomputing and mainframe business.

However, the clones that followed the 5150 - generally cheaper, faster, better specced or even sometimes all three of these things - were hugely significant in making the IBM PC successful.

So it was perhaps odd that when the company came to design the replacement for the original PC in 1985, it would declare that the cloning must cease.

Rod Canion, Compaq's president, seemed to accurately forecast the outcome of that decision, when he suggested that the "technology upgrade in MCA was marginal and that the radical design and closed architecture would be a major problem for IBM"[10].

There were some positive signals for IBM at the beginning of 1989 as Apricot launched its genuine PS/2 clone with a full MCA bus - the first UK manufacturer to do so[11] - and there appeared to be some wavering in the "ranks of die-hard anti-MCA folks", according to Guy Kewney in Personal Computer World, as over in Taiwan the company Mitac signed a licencing deal with IBM giving it the rights to develop its own MCA-based system.

Mitac, which Kewney reckoned had clearly launched a PS/2 clone for appearanced rather than for the market, was having to fork over between 1% and 5% of every machine it sold by way of royalties - and that was on top of a baseline 1% levy.

In a press release, the company admitted that it was a step "towards raising the reputation and relationship both Mitac and Taiwan have internationally".

There was also the French company Normerel, which had managed to beat IBM when it released its 386SX-based MCA machine.

Although it wasn't that well known - its machines were targetted at "value added resellers", who would stick their own name on the box when they shipped it - it was at least proof that not everything originated in the US.

Normerel's machines even had a bunch of switches on the back of its machines which could be configured to set the BIOS boot and error messages to the correct language[12].

Elsewhere, the news was more mixed, as whilst Dell revealed that the reason it had postponed its MCA machine was more to do with issues in its production line than it was to do with market pressures, Tulip was announcing that it believed there was no viable market for Micro Channel micros, before it went ahead and launched one anyway[13].

Waiting for the EISA bus

By the end of summer in 1989, there still hadn't been any real sign of EISA actually appearing, even as IBM was said to be finally getting its act together over its own MCA.

At an EISA event held in summer, there wasn't much to talk about, other than the potential of 40 million installed PCs and the chance of capturing 50% of the market, whilst Intel was showing off some of the hardware it had promised during Comdex Spring, the previous April, in a Perspex-covered AT systems box.

Even the original intention of EISA, which was to provide a direct replacement for MCA in a way that ensure backwards compatibility seemed to be shifting, as the consortium was beginning to admit that it might have to charge higher prices in order to recoup development costs, and that it might end up being aimed higher up the market than the average consumer.

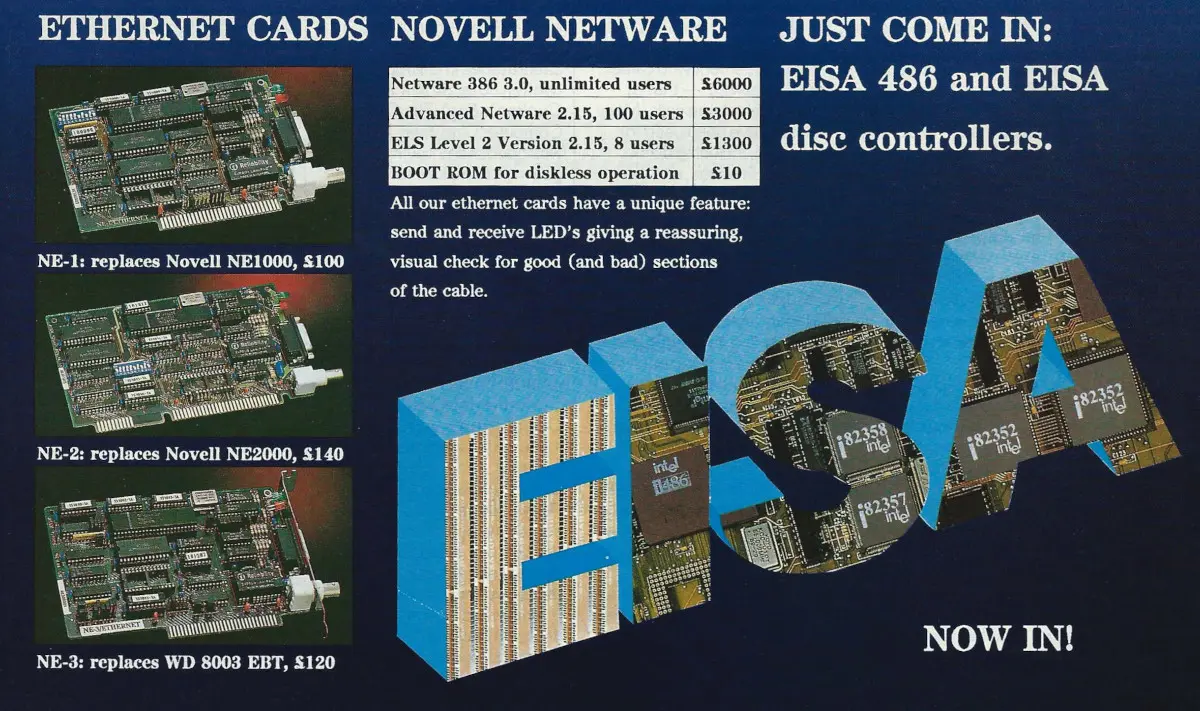

A promotion for EISA cards from a Solidisk Technology Ltd advert in August 1990's Personal Computer World, including the NE-1 and NE-2 updates for the legendary Novell NE1000 and NE2000 network cards, with the latter retailing for £140, which is around £430 in 2026. There's also a copy of Novell Netware 3.0 for sale - supporting unlimited users - for a whopping £6,000 - that's around £18,600 in 2026

Meanwhile, the presumed leader of the Gang of Nine - Compaq - was keeping a low profile as it had just signed a deal with IBM, in which the two gave each other worldwide non-exclusive licences to their patent portfolios on anything filed before July 1993.

However as Compaq had a much smaller patent pile than Big Blue, it was also having to make a payment in return for Compaq's previous use IBM's AT bus, although the deal did also give it some protection from any more significant punitive claims over historical cloning activity.

Despite all of this, Rob Canion - Compaq's chief executive - was still denying that the company had any plans to build its own MCA machine, even though it wasn't entirely clear whether Compaq could go ahead with its plans for EISA hardware without annoying IBM[14].

Whilst EISA itself didn't end up dominating the market, apart from perhaps in high-end servers, the ISA part of it - essentially a standardised AT bus - did.

This was in part thanks to the fact that IBM had defensively patented the MCA bus, plus it was also the momentum of the huge user-base that had already built up around the older AT/ISA standard.

This all meant that it would be the ISA bus that would stick around and rule the PC world until PCI kicked it into the long grass in the mid 1990s.

Meanwhile, American Research, for its part, was also selling its own machines directly via mail order - in a deal which also included some limited on-site support - which for the UK and the wider European market meant importing its machines from Taiwan but assembling and quality-checking them in Croydon.

It was fairly unusual in the clone market as it wasn't selling its machine on the basis of price, but on speed, reliability and the fact that it was planning (like everyone else, obviously) to stay around in the micro industry[15].

It clearly had some chops as its ARC 286 Turbo was rated the fastest computer in a test run by Arizona State University, beating micros by IBM, Tandy and Epson[16].

The end of the golden age

Dell, and companies like it, represented the end of the "golden age" of microcomputers and the start of the commoditisation and standardisation era, where the industry had more-or-less completed its transition from hundreds of companies selling hundreds of different machines to a few dominant companies and hundreds of also-rans all selling the same thing - clones of the IBM PC.

Commodore might still be selling its Amiga, Atari the ST, Apple the Mac and Acorn the Archimedes, but with the exception of Apple, which managed to cling on to a 5-10% and occasionally 15% market share thanks to its ownership of the designers-and-DTP market (and then its move into the luxury/aspirational consumer goods market), and - indirectly - Acorn's ARM spin-off, it was game over.

By 1989, commoditisation of the PC market was so complete that it was no longer just about a few companies building their own IBM PC-compatibles.

Instead, it was the era where companies from the Far East were supplying just motherboards and associated components which absolutely anybody could build a PC around.

As Guy Kewney pointed out in May 1989's Personal Computer World, if a couple of hundred UK PC dealers were to start building their own PCs around these generic motherboards, at only a few dozen a month, they would rapidly become the third- or even second-largest suppliers of PCs in the UK.

However, it wasn't all plain sailing, because as technology improved and PC speeds increased, the tolerances at the circuit level were getting a lot tighter.

For instance, on the older PCs, a signal glitch could be as long as 80 nanoseconds, and it wouldn't register as a real signal.

By the dawn of the 33 MHz machines, this was down to around 6 nanoseconds, and it was only going to get even more challenging from there.

Glenn Henry, Dell's head of R&D, admitted that even Dell had been such a builder, buying parts and "slinging them together", but that it had started getting into trouble with such an approach by the end of 1988.

The company was even forced to hold off on its 20 MHz 310 model as it was finding that it wasn't getting the same data out of memory from one read to another.

As Henry said, this required that Dell had to have "a properly engineered range" and that was why the company "held back on the new machines until [they] had it"[17].

--

The transition from an "infinite variety" to a PC homogeny could even be seen in the state of once-legendary computers shows like the West Coast Computer Faire - the show which had introduced the public to machines like Commodore's PET and the Osborne 1.

By 1986 it was becoming something of a disappointment and no longer, according to a letter in Personal Computer World, "an opportunity to feel the pulse of a young, truly innovative industry"[18].

In the same year, the show's new owners - Interface Group, a company that usually seemed to be known for "boring business conferences" - re-hired the faire's original creator, the enthusiastic amateur Jim Warren, in an attempt to "put the old-style show back together again".

The attempt, which included reinstating the popular and much-loved conference sessions, which had been dropped because they weren't profitable, seemed to be making headway, with Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World "looking forward to next year's faire[19]".

Meanwhile, other gloomy sentiments continued into the end of the decade when Popular Computing Weekly commented on how boring the 1989 Which Computer? Show had become if you were a home micro owner, with only Atari and Commodore having any sort of presence[20].

The conclusion seemed to be that it was the end of the gold rush of random-machines-of-the-month that ended up in the loft gathering dust, but was now the era of maturity, where the computer was no longer a hacker's hobby or a home games machine, but had graduated to a general-purpose tool in the world of work - an environment that demanded consistency, reliability and - above all - conformity.

Date created: 23 September 2017

Last updated: 14 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.