Cambridge Computer Advert - November 1987

From Your Computer

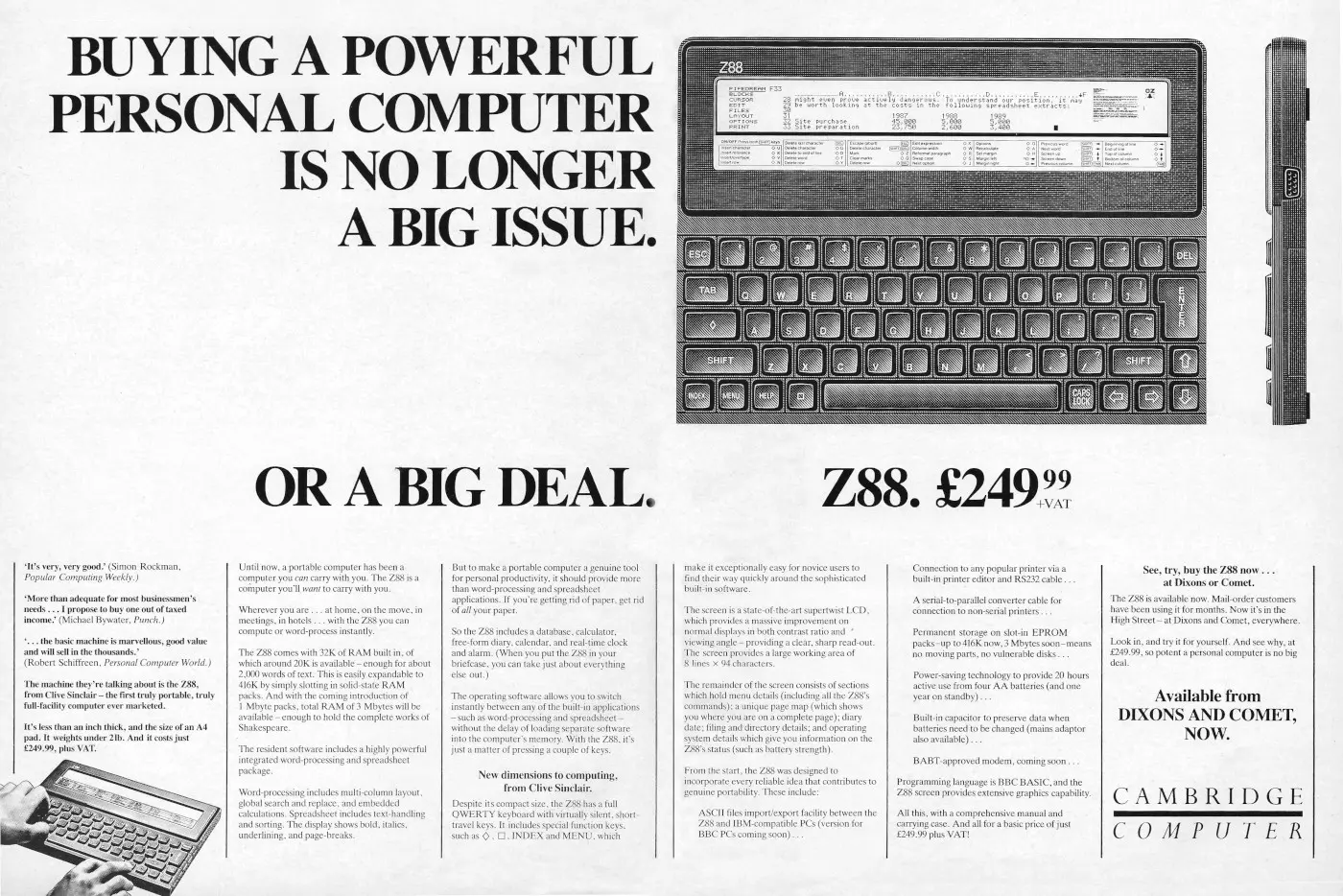

Z88: Buying a powerful personal computer is no longer a big issue. Or a big deal.

Clive Sinclair's company - Sinclair Research - had hit the buffers towards the end of 1985, and was sold - essentially for its name and merchandising rights - to brash new upstart Amstrad in 1986.

Uncle Clive was left with the debt-laden part of the company, which became Sinclair Research Limited, or SRL.

A year later and Clive Sinclair was back with a new company - Cambridge Computer - and its first computer, the Z88 portable - a name with more than a nod to the old Sinclair's famous micros the ZX80, ZX81 and ZX Spectrum. It very loosely derived from Sinclair's fabled Pandora project, although perhaps more in its industrial design than in its technology.

In the summer of '87, Cambridge Computer ran a campaign to attract software developers to its new machine.

Its "Authorised Third-Party Development Programme" was intended to give "as much technical support as possible" to anyone interested in developing for the Z88, with an option of space on the Z88 stand in September's Personal Computer World show in return.

CC's marketing manager Peter King said that "Comms will be big business on the machine, but we're also hoping people will publish software with vertical markets in mind - stock control, that sort of thing.

There has also been interest from companies in writing text adventures for the Z88, and things like chess and backgammon could also prove popular"[1].

The retail price of £287 (including VAT) was about £1,050 in 2026 terms, and marks an increase from the £199 + VAT the machine was selling for on its release in the spring of 1987. The cause of the £50 increase was said to be the strength of the Japanese Yen[2].

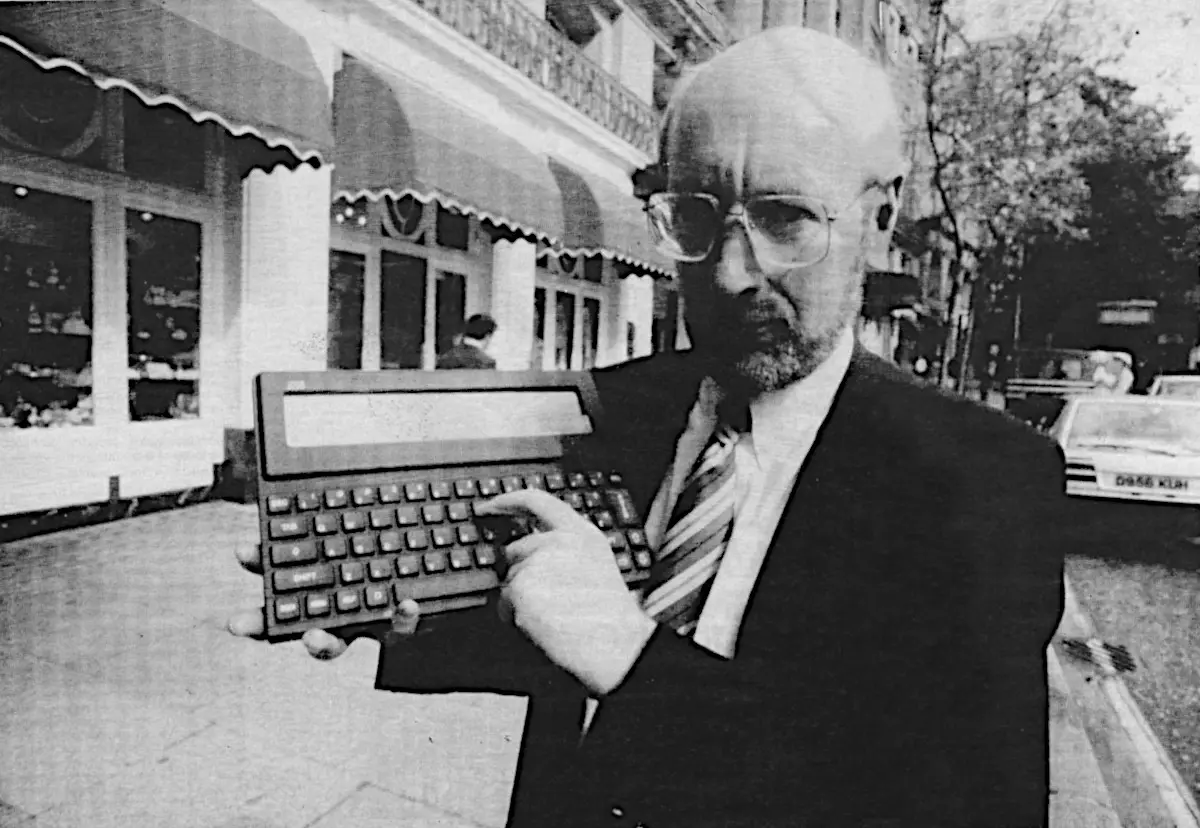

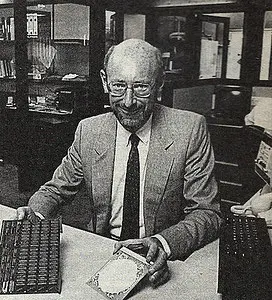

Clive Sinclair and his Z88 outside a hotel in the UK somewhere. From Your Computer, December 1987

It's pleasing to see that some of Sinclair's famous clichés are still present in the new company's advert with several mentions of "coming soon..." hardware and software, like the aforementioned BBC communication program and a BT-approved modem.

Also present was a bit of post-launch recall panic as Cambridge Computer announced that some mail-order Z88's would need to be returned in order to have the machine's operating-system ROM upgraded in order to handle new software that was now being written for the machine.

CC's marketing manager Peter King played down the issue by pointing out that the problem only affected "the first few hundred machines shipped"[3].

Whilst Alan Sugar, the buyer of Sir Clive's previous Sinclair Research, turned up just for the first trade-only day at the 1987 Personal Computer World show in Olympia, Sinclair himself was there for the duration at Cambridge Computer's suitably matt-black stand, which harked right back to the days of the ZX81's marketing and style. Reporting on the event, Popular Computing Weekly's Gordon North wrote:

"[Sinclair's] little black portable Z88 was one of the few things at the show that I found myself returning to over and over again. His stand was small compared to his neighbours and there were times of the day when the light didn't get to it, but Sir Clive has still got pulling power. I visited that stand again and again until I really began to believe that I could formulate a spreadsheet on the train without being sniggered at"[4].

Wafer Scale

One of the post-Amstrad Sinclair Research Holding's other new companies, besides Cambridge Computer, was Anamartic - a greek word meaning "fault free".

This was set up to continue the wafer-scale integration technology that the previous Sinclair had started at its Metalab research centre at Milton Hall, a building which Anamartic continued to occupy (for a while, anyway) post-buyout. 14 staff had transferred directly over from Metalab, but Clive himself was taking something of a low profile at the new company as a non-executive director.

Clive and one of his silicon wafers, © Popular Computing Weekly, December 1985When the new Sinclair announced its "new world lead in semiconductor technology", it went on a fund-raising round to seek the extra cash it needed to take its final prototype to commercial production.

Malcolm Wilkinson, Anamartic's general manager said:

"We have a prototype. To get that into high-volume production, more testing and so-on is needed, plus the expenses of marketing it. We are looking for about £6 million, from a mix of corporate investors, venture capitalists, people like that"[5].

The company had initially been looking to raise £50 million back in the summer of 1985 when it was launching the wafer-scale project, but by the very end of 1985 it was claiming that it at least had the first £5 million in venture capital.

The modest shortfall meant that initial manufacturing would need to be farmed out, with production not moving in-house for another three years, at which point it was thought another £40 million would be needed.

At the same time parent company Sinclair Research was thought to be in need of another £10 million just to keep it going - a sum that Sinclair thought might be made up of contributions from "organisations and wealthy individuals".

Meanwhile, Robb Wilmot, who had helped set up the wafer project, had resigned as chairman of ICL but was now ruled out of any further involvement as he headed off to concentrate on his own businesses[6].

The first product - the solid-state mass-storage device - had been mooted for the QL, and was something that was half-way between a hard disk and regular computer memory, but which had battery backup.

Anamartic's first round of investment was funded by Barclays Bank, which put in an undisclosed "large sum".

This funding round was topped up with a further £2.8 million at the end of 1987, with £1 million from US computer company Tandem, and some additional spare change from SGS Microelettronica, Baronsmead, Advent and Murray Technology.

This seemed to be a vote of confidence in Sinclair's technology and contrasted with US IBM-compatible mainframe maker Amdahl, which had apparently spent $150 million on wafer-scale integration before abandoning the project[7].

Catt amongst the pigeons

Sinclair's wafer-scale memory devices were developed from the 1978 designs of Ivor Catt, a man who had made some enemies over the years by suggesting that the classical Von Neumann architecture of computers - where a central CPU controlled all the memory, did all the calculations and managed input/output, was essentially "bunk".

After several years maintaining his ideas at places like Middlesex Polytechnic and running digital electronics courses, he popped up again at Sinclair.

Sinclair's product - essentially a solid-state Winchester disk - wasn't quite the culmination of Catt's dream, but at least it was using his technology, albeit using blocks of RAM instead of the original serial memory design that Catt had in mind.

The fundamental problem of producing a single silicon wafer was that imperfections would mean that certain parts of the chip wouldn't work, which would normally mean rejecting the entire wafer.

This was solved for conventional chips, which were cut out in their tens from a single wafer of silicon, by simply discarding any chips that didn't work, however Catt's Content Addressable Memory solution allowed the wafer to determine for itself which were working sections of memory by injecting test patterns into each section and seeing which could be read again, meaning not only that in more cases the entire wafer was usable but that the entire thing was inherently fault tolerant[8].

The first units from Anamartic, expected at the end of 1988, were to be CMOS, but Sinclair saw the development of bipolar technology as crucial, as this required about one twentieth the voltage to drive the bit-switching transistor.

The whole idea was really 25 years ahead of its time, with the rise of solid-state disks based on various forms of Flash memory only becoming commercially viable from around 2005. However, back in 1987 Sinclair had already seen this coming:

"I think solid state has to dominate. I have never believed that disks were the best way to go. There is no doubt in my mind that the whole computer world will change over - not overnight, but it will happen".

Martin Banks, frequent contributor to Personal Computer World, offered an analysis of Clive Sinclair:

"The thing that strikes me about Sir Clive is that he can actually see far too clearly, far too far into the future. And he's dead right. Disk technology is getting horrifyingly anachronistic ... but it's going to be around for years and years because there are so many people using it. He's absolutely right, but it wouldn't surprise me if it takes until the turn of the century for him to be proved right"[9].

Given the normal track record of technological future-gazing, being only five or so years out was remarkably prescient.

Sinclair was also excited about a possible wafer full of Transputers - the British-designed parallel-processing RISC chip that had been developed at great expense under the auspices of the National Enterprise Board and which was already being mooted as a processor for a new Atari machine. Sinclair continued:

"Years ago I was in the States and I realised the future of computing had to be parallel processing. I had one of those brainstorms we all have and thought 'Christ, we'll never do it - the pin-out problem alone will kill it!'. Wafer-scale integration [as a way to connect multiple parallel processors without the expensive faff of having to wire them all together on a motherboard] is fundamental. It's not an option, it's a necessity".

Anamartic started shipping its wafer-scale solid state memory at the beginning of 1990, in the form of its "Wafer Stack" high performance storage device.

Offering some 100 times the speed of regular hard disks, the Wafer Stack came with one or more 40MB modules - up to four in total, or 160MB.

As well as its existing methods to route around failed components on the wafer, the company had also developed its own programmable logic which enabled each of the hundreds of 1Mbit chips on a wafer to communicate with the next and so present as a single large storage area. Anamartic's chief executive, Peter Cavil, stated:

"while traditional chip manufacturing techniques often result in only 25% usable chips on a wafer, our technology allows us to use about 80% of the bit capacity on a wafer. This means that the Wafer Stack storage module can provide significantly better price /performance than solid state disks based on traditional discrete chips"[10].

That might have been so, but a 40MB system with SCSI interface still rocked in at $11,680, or about £22,700 in 2026.

Chips and MIPS

During the summer of 1989, news of another of Sinclair's chip developments leaked, at least slightly, in an edition of BBC's Horizon, which was about Sinclair himself.

The new chip - the PCG-1 - was co-designed with Chris Shelton, the man who had designed one of the UK's first - and for a while most popular - micros, the Nascom 1.

The new chip was already the subject of much gossip around Cambridge, as it was rumoured that it was going to be very fast, clocking in at around 150 million instructions per second, or MIPS.

Or rather, not clocking in, as another rumoured feature was that it was to be a "free running" chip, in that it had no actual clock - unlike pretty much every other conventional processor - and would execute instructions as fast as it could, at least until it had to do stuff like communicate with the outside world.

Writing about a previous encounter with Shelton, Personal Computer World's Guy Kewney recalled how the Nascom designer had suggested that computer scientists all went about writing programs back to front.

Instead of starting with a language and coercing it to do what they want, they should write out the program instructions and write an interpreter to run it, which was how Shelton had worked for may of his projects.

The design of his new chip for Sinclair had this in mind, with the chip created to be able to do lots of new things and only when it could do them would they think about stuff like emulating boring old 8086s.

To help achieve this, the new chip came with 256 bytes of fast ROM into which customers could write their own instructions - with Sinclair then supplying a bespoke chip with the custom instructions built in, a bit like how modern FPGA chips are "programmed" to do particular things.

Shelton reckoned that all this would be available within the next 12 months, but before that Sinclair also had an MS-DOS-based computer to launch as well as a "bicycle in a briefcase" project, which was apparently a real thing and not a joke, unlike rumours of an electrically-powered plane - an idea which is actually now being realised, some 30 years later[11] - where the only drawback was said to be the 100-mile mains cable[12].

When asked to elaborate upon the ultra-portable bicycle, Sinclair was said to have suggested that he was thinking of naming it "after Norman 'on-yer-bike' Tebbit" - one of Maggie Thatcher's cabinet ministers who had suggested that unemployed people get on their bikes to look for work, and who was also seriously injured in the Grand Hotel IRA bomb, where Acorn's Chris Curry was also in attendance.

In the same interview with Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World, Sinclair was quizzed about plans for a bigger Z88, which had just gone on sale in the US via merchandising company Diversified Foods.

Instead of answering, Sinclair replied "I've often wanted to do a bicycle, one which you wouldn't know you have".

However, he eventually conceded that there was something going on, saying "what we're working on is not a replacement for the Z88, and it won't be out this year".

He continued "Who's telling you this anyway? We've only spoken to two people about it. You're way, way too early"[13].

Future imperfect

Whilst Sinclair often had a spookily-accurate grasp of the future, he didn't always get it right, for instance when he claimed in an interview for Practical Computing's July 1982 edition that the ill-fated Sinclair Microdrive was "miles ahead of what anyone else is doing", shortly before the 3.5" floppy cornered the market.

His dream that expert systems - now generally re-branded as Artificial Intelligence, or at least Machine Learning - would replace doctors and schools because computers "will teach better than human beings because they can be so patient and so individually attuned" is also still some way off, although it's certainly not ruled out.

However he did offer some interesting prognostication on what might be the impact of the Internet and social media, some 20 years before Facebook launched in the UK.

Discussing the threat to normal personal communications and the "de-socialising influence" of expert systems, AI and networks - as highlighted in a report published in New Scientist earlier in 1982, which suggested that networking buffs "became withdrawn from their everyday lives and preferred to communicate with their on-screen pals" - Sinclair said, in what could easily read as a prediction of the death of the High Street at the hands of Amazon and the like:

"Yes, I am concerned with this. We have to watch very carefully that you do not remove the rituals of things like shopping or banking. Sometimes it is possible for something to disappear before people realise what it is they want to keep".

The same interview discussed how advances in computers could lead to experiences that were better than normal life, like those available on ultra-expensive military flight simulators, or in other words Virtual Reality.

Sinclair clearly didn't forsee a world where VR could be achieved by lashing a smartphone to the front of one's face by using an absurd goggle-box covered in polyester fur, but instead suggested "a three-tube projection TV with a 50" full-colour CRT display [or where] the optics and electronics could be fitted into a shoe-box-sized unit projecting onto the wall-mounted screen"[14].

See also Sinclair.

Date created: 02 October 2019

Last updated: 11 December 2024

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.