Acorn Advert - September 1981

From Computing Today

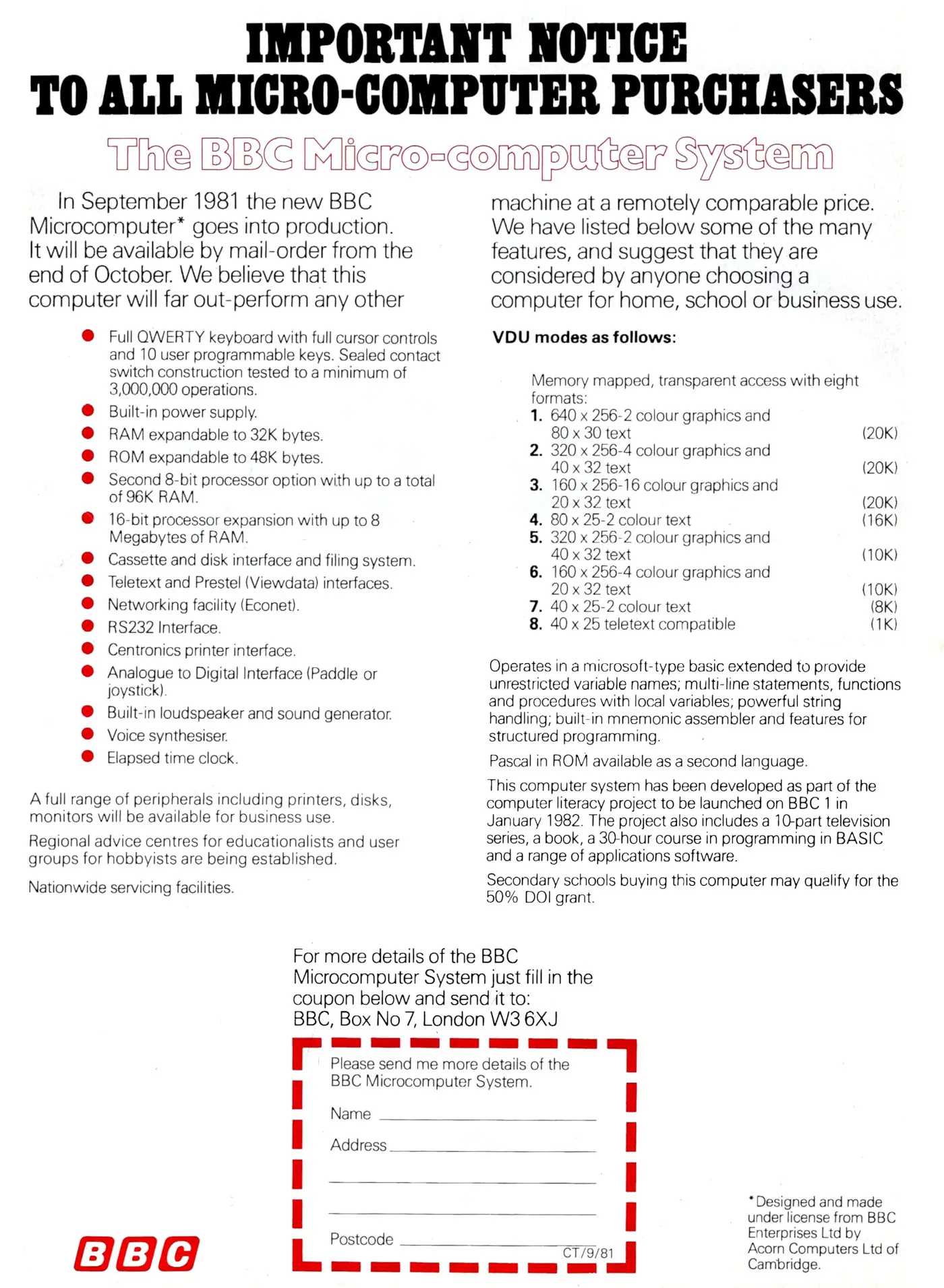

Important notice to all micro-computer purchasers: The BBC Micro-computer system

This is perhaps the advert that really started it all for Acorn, at least in terms of the Acorn Proton, a.k.a. the BBC Micro.

It announced the upcoming availability of the new BBC Microcomputer System from "the end of October", a statement which ended up being hugely optimistic as the machine didn't properly start shipping until well into the following year, with just a few machines appearing from the 1st December 1981.

Even when it did ship, it wasn't easy to get hold of one[1], as by Christmas 1981 Acorn was already running a backlog of 9,000 orders[2].

It got even worse as the Proton was still not widely available even when the BBC television programme that was dependent upon it[3] was scheduled to start broadcasting in January 1982.

The broadcast date was postponed to afternoons and early Sunday mornings in February[4] where it was clearly hoped that not too many people would watch it, with a repeat in March of that year to allow time for Acorn to sort out its production and delivery chaos and get more machines out to the public.

It was however broadcast as planned to schools, with the first programme going out on the 11th of January.

The pre-emptive announcement caused Acorn other problems too as it put the company's existing model - the Atom - under a bit of a sales cloud, leading to something of an "Osborne effect" and causing some financial hassle which Acorn did well to survive[5].

By May 1982, Popular Computing Weekly seemed to have more-or-less decided that the whole BBC Micro/Computer Literacy Project (the name for the BBC's overall scheme, of which the micro was just a part ) was a fiasco, suggesting that the BBC had taken too long to decide on the design of the computer, and had allowed too little time for production problems to be sorted out.

It also accused the Beeb of woefully underestimating demand, suggesting that its forecast of 12,000 units shipped by the start of 1982 - of which only 300 fully-working units had been produced by January[6] - was a bit far off the 50,000 it was expected to actually sell in the first year.

At least the BBC had a history of low guesstimates - when forecasting in 1965 how many new-fangled colour televisions would be sold during the first ten years of its colour service - launched in 1967 - it suggested 750,000, whilst the real figure was 8 million[7].

Popular Computing Weekly concluded "Would that British industry, broadcasting, and Government were so unfettered by caution and timidity"[8].

It was not just the BBC which was underestimating, as Acorn's earlier machines had only ever sold in the tens of thousands.

Original BBC Micro co-designer Steve Furber suggested that they first got an inkling of the machine's success when he, Sophie Wilson and Chris Turner gave a talk at the Institute of Electrical Engineers in London. He said:

"The first sense I got that this thing might exceed our wildest dreams was when we were lined up to give a seminar at the IEE Savoy Place in 1982. The main lecture theatre seats several hundred, but three times the capacity turned up. Coach-loads of people had come some distance, for example from Birmingham, to hear about the BBC Micro. A lot had to be sent away to avoid exceeding the safe capacity of the lecture theatre. We were booked to give the seminar two more times, and many other times around the UK and Ireland, just to meet demand"[9].

Newbury drops the ball

The BBC's Computer Literacy project had started in earnest in 1980, as a follow-up to the corporation's programme on computers, The Silicon Factor, which first aired in April of that year[10].

It was largely driven by John Radcliffe and David Allen as part of the BBC's Further Education team, based in Ealing Broadway, but was also touted around various other BBC departments, as well as education groups like the National Extension College.

This was in some ways seen as unfortunate, as almost immediately inter-departmental wrangling started over the project.

Meanwhile, the BBC's engineering team was given the task of investigating whether a specification for a computer could be drawn up which was sufficiently common to apply to most potential users.

At this point, other groups such as the Department of Industry, educational software group MUSE, and the BBC's own Enterprises division - which was keen on the potential revenue to be made by selling a computer to go with the television series - got involved, with the latter being particularly problematic as it shifted focus away from the programs onto the machine itself.

It also led to inevitable "decision by committee" over issues like which processor should be chosen, whether it should support Viewdata and telesoftware, what language it should use, and how much support should be made available.

Eventually, under pressure from the DoI, the decision was made to choose the NewBrain - a machine which seemed to have been under "endless development" at Newbury Laboratories, which was then a subsidiary of the same National Enterprise Board that had baled out Sinclair a few years before.

In fact some thought that the specification was actually tailored to the NewBrain - it was sometimes said "the machine came first and the spec second" - possibly so that the Department of Industry, keen to boost British microcomputer manufacturers, could indirectly favour part of the industry without any of the obvious direct subsidies that the Thatcher Government so despised.

Despite that, the government still wanted to encourage the wider UK microcomputer industry, with Thatcher speaking at the Department of Industry in the spring of 1981 and saying:

"We want to be in this world of microcomputers and we want to be in it big"

Unfortunately, due to ongoing delays and the increasing likelihood that the NewBrain would fail to meet the BBC's specification, it became clear that Newbury would not be able to fulfil the contract, and so the NewBrain was ruled out at the end of 1980.

When the NewBrain was dropped, there was a swift revision of the specifications which a carefully-selected set of companies - Acorn, Sinclair, Tangerine, Research Machines, Transam and Nascom - were given less than a week to build a prototype against.

The new specification was developed by a BBC team which included Charles Sandbank, the head of BBC Research, Richard Russell of BBC Designs and John Coll of MUSE, along with additional input from consultants Ray Kernow, John Sweeton and Peter de Bono.

Included in the specification was a requirement for 16K of memory - upgradable to 96K - an add-on teletext receiver, Prestel interface, high-resolution graphics, networking and a keyboard "with a positive action like a top-class electric typewriter[11]".

The original requirement for a Z80 processor was dropped, and replaced with the 6502, with the final updated specification said to be "closely modelled on the successful Acorn Atom[12]".

This didn't impress the Amateur Computer Club, which would have preferred the Z80 or Intel's 8085, both of which had a future upgrade path, unlike the 6502, even though this was the chip running many of the popular micros of the day[13].

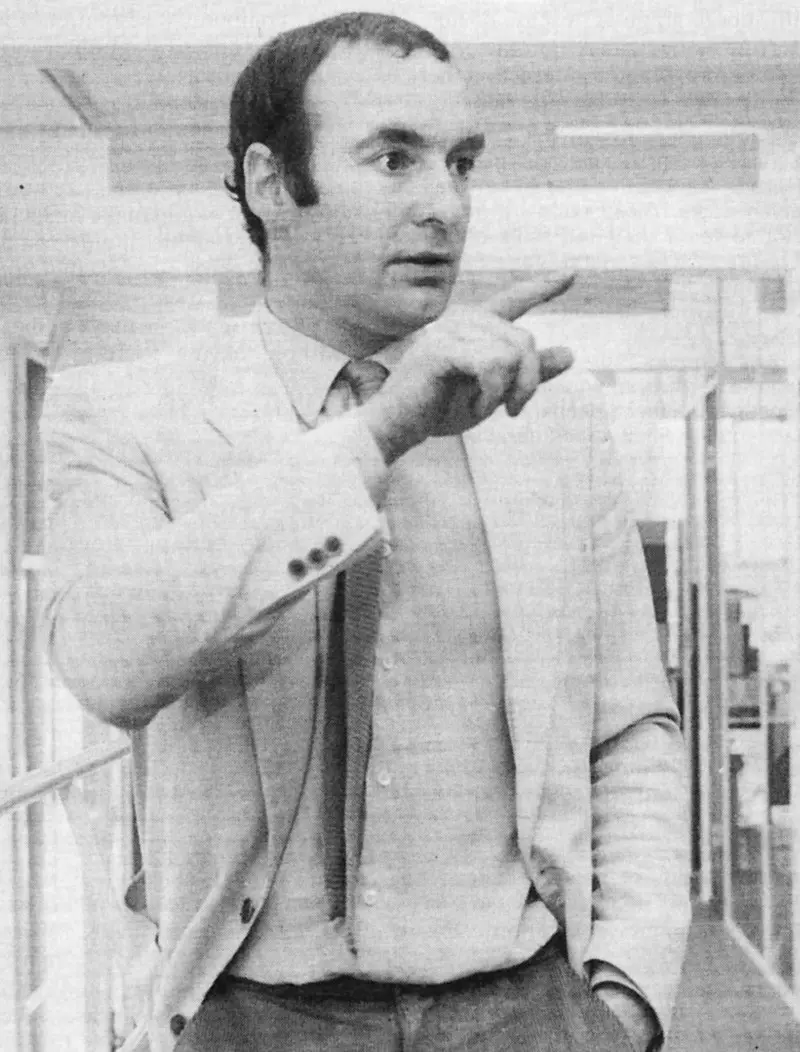

Acorn's co-founder Hermann Hauser in 1993, from Personal Computer World, May 1993Luckily for Acorn, it was already working on designs for a follow-up to the Atom with a machine called the Proton.

This - unsurprisingly - needed very little adaptation to fit the new spec, and so it was effectively a shoe-in. Acorn described its BBC machine as "a condensed version of the new Proton"

It was known that the Department of Industry also favoured Research Machines' 380Z, although the DoI seemed pragmatic enough to realise that the Proton was likely to offer a more affordable alternative[14], particularly as Acorn originally claimed it would be available for "less than £200".

Sinclair, which seemed to think it hadn't been given a fair chance, wasn't actually that amenable to adapting its existing ZX81 specification, which was already developed but not yet launched, or that of its upcoming ZX82/Spectrum, and felt that the BBC should instead adapt its specification to suit Sinclair's existing machines instead.

Although the ZX81 was even less like a real computer than the upcoming Spectrum, it was certainly very cheap - at only £70 - and it seemed to some that it was a mistake to overlook Sinclair's ability to churn out machines, compared to Acorn's difficulty in even meeting the demand for its existing models. As Guy Kewney wrote in December 1981's Personal Computer World:

"Quite why Sinclair, with a proven track record of mass-producing cheap computers didn't get the contract, while Acorn, with the Atom not long launched and only just gearing up into full production did, will probably never be known. The most probable reason is that the BBC wanted a more sophisticated machine and Acorn was working on a design which would fit the requirements without too much modification[15]".

Meanwhile Acorn was going out of its way to be flexible, or as Chris Curry said:

"We were being absolute tarts about it. We were doing just what the BBC wanted us to do and Clive certainly wasn't doing that".

Acorn's impossible prototype secures the deal

Hermann Hauser recounted the story of the development of the prototype leading up to the BBC contract in an interview published in May 1993's Personal Computer World, saying:

"They came to see us on a Monday and they told us the specification of this computer, and it was just typical BBC. It was way over the top in every way: the amount of processing power, the integrated graphics, the connectivity it had to have for the rest of the world, the printers... basically, they wanted to make a programme about the computer industry, so this thing had to do everything that you’d ever thought of. By a stroke of luck, Acorn had a design that was just a little bit better than what the BBC had asked for. We thought it couldn’t be built, that it was over the top. So on the Monday I got on the phone and said to Steve Furber: 'What's the chance of building a prototype by Friday?' He said: 'Completely out of the question: there's simply no way this can be done.' So I rang Sophie Wilson and said: 'Sophie, I’ve just had a word with Stephen, and he thinks it’s really hard, but if we really tried we could have a prototype by Friday.' And Sophie said: 'Absolutely no way, but if Stephen says it, I'm in.'"

The company also hired Ramesh Bannerji - the "fastest gun in the west", according to Hauser - from the Computer Lab. Bannerji was a wire wrapper responsible for wiring up connections between components, and could wire-wrap "as fast as people call out the connections", apparently without ever making a mistake[16].

The Acorn team worked around the clock for three days and nights to get their prototype working and debugged, and finally had a machine running by 7am on the morning of the BBC's visit.

"It was always his job to go out and buy the kebabs"

The final blocker which was preventing the prototype from working had been an "umbilical" bell-wire clock/timing connection between the prototype and its parent development system. Steve Furber, one of the Proton's designers recalls:

"We were all getting very tired, but Hermann was very good at team motivation. It was always his job to go out and buy the kebabs and he would make the tea. He would do all these things just to keep people going. We were all staring at this thing that was still refusing to work and Hermann suggested something like 'cut the umbilical cord from the prototype to the development board and let it run on its own', which seemed completely daft but we were all out of ideas. So we tried it and the whole thing sprung into life. It was a major irritation that Hermann made the final suggestion that caused it to work!"[17].

By the time the BBC team arrived for their 10am meeting, Acorn had BASIC running on the prototype, and by the afternoon it had some graphics running as well.

Executive producer for the BBC, and now the man responsible for running the Computer Literacy Project, John Radcliffe, recalled that:

"it was an impressive demonstration, which significantly influenced the BBC's subsequent decision".

Whilst Tilly Blyth concluded in her anatomy of the legacy of the BBC Micro, published in 2012, that:

"The BBC was well aware that the Acorn team had made more progress in a week than the Newbury team had managed in two years"[18].

The controversy begins

Even before Acorn's Proton started shipping, rival manufacturers were complaining about it, in particular Commodore UK's Bob Gleadow, and - unsurprisingly - Clive Sinclair.

Sinclair had already claimed that it could after all supply a machine to the BBC's specification for a retail price of £110 (about £610 in 2026), with Clive Sinclair stating that the broadcaster had not conducted "a full enough review of the latest products available". He also told Practical Computing in its May 1981 edition that:

"We did quote for it. We had a specification from the BBC but it wasn’t very full and there were some ambiguities in it. We said we could build it for £110 but it was clear our bid wouldn't come to anything. We had to put in a bid to protect ourselves. We feel that the BBC should have talked more to the industry and made the specification better known. We think it's crazy. Here we are trying to compete with the world's industry and our own national broadcasting system is operating against us".

Charles Sandbank of BBC Research disagreed with Sinclair, saying:

"The BBC has taken advice from a great many people with experience of the micro industry. As an employer of engineers, I think it’s a worthwhile machine but it’s a very difficult decision. The BBC has gone into it very carefully and has done all the right things and has gone for the solution which seems to have the highest probability of doing what it wanted[19]".

Sinclair went on to suggest that it was going to launch its own £15 million alternative scheme and provide a machine equivalent to the Acorn/BBC micro - with a free ZX printer, free copy of Logo and ten vouchers worth £45 off more Spectrums[20] - for even less money to schools. The company said that:

"With the printer, the product will be offered at about £90. It is impossible to compare prices because the rivals do not offer such a facility. Our products, like the others on offer, are British made".

Sinclair - apparently "unabashed by delivery delays of up to three months for Spectrums" was also claiming that it could deliver micros into schools within six weeks.

Commodore, meanwhile, wasn't really in with a chance as it wasn't considered as a British manufacturer - even though it had been building PETs in Stockton-on-Tees and then Slough since the late 1970s - so the company's angle was more on making sure that the version of BASIC chosen for the Proton and the BBC's television programmes would be compatible with its PET and soon-to-be-launched VIC-20 machines.

Head of Commodore UK, Bob Gleadow, stated:

"We have contacted John Radcliff, executive producer of continuing education, and welcome the decision by the BBC to adopt a more standard form of BASIC to that presently available on the Acorn machine"

Gleadow also predicted that Acorn would encounter problems with the time-scale given by the BBC to develop a new BASIC interpreter - although development was already underway at Acorn - and suggested that the BBC meet with Commodore to ensure the maximum software compatiblity between the Proton and the VIC-20[21].

Naturally, this all came to nothing with the two machines' BASICs being incompatible in almost every way, despite both micros using the same MOS Technology 6502 processor, and both being nominally based on the same underlying Microsoft language - although Acorn's was based on Version 5 whilst Commodore was still using essentially the same version it bought for the Commodore PET back in 1977.

Acorn's BASIC was also significantly extended by Sophie Wilson, who had been influenced by Algol L and BCPL - the language written by Martin Richards at Cambridge University's Computer Laboratory and which spawned the language "B", and from that the more-famous and much more widely used C.

It had started from a 12K chunk of working language, with Wilson modifying it in the direction of Pascal - another major influence - giving BBC BASIC a much more structured style than the original Microsoft version.

This was done under the guidance of John Coll, consultant to the Microcomputer Users in Secondary Education (MUSE) group, who helped ensure that the language remained BASIC-enough to be understood by the end user. This meant in part that it was still possible to write in "pure" Microsoft BASIC, as a subset of the BBC language.

There were other grumbles within the industry as well over the choice of BASIC as the BBC Micro's "natural" language, with some "lively debate" over which would be a better choice. Pascal and COMAL fans were apparently the most vocal in proposing their chosen language.

Wilson explained why COMAL - the "Common Algorithmic Language" developed originally by Børge Christensen of Denmark in 1976 - in particular was not chosen, saying:

"While COMAL's structure is better than BASIC, it cannot compete with BASIC for straightfoward ease of use and small size. Perhaps COMAL is better than the BBC realised, but on the other hand, our BASIC is far more powerful than people seem to think[22]".

Clive Sinclair was also vocal about Acorn doing its own thing, saying, seemingly without actually having seen Acorn's version of BASIC, that:

"What the BBC is doing it is doing badly, and it is damaging the whole progress of computers in this country. We have put a new version of BASIC into our machines. It has been highly praised in the UK and abroad because of its editing facilities. It is silly to ignore progress. What the BBC has offered is Microsoft BASIC. If we had wanted to use Microsoftware we could have bought it off the shelf for $10,000".

This was perhaps ironic given that Sinclair's BASIC - whilst impressive from the perspective of initially squeezing it into 4K of ROM on the ZX80, from which ZX81 and Spectrum BASIC also derived - was known to be amongst the slowest BASICs on the market at the time.

Ultimately, market pressure was the biggest reason to choose BASIC. Whilst COMAL, Pascal and the rest might produce "tidy, academically-satisfying structured programs" from the start, they were just not as easy for non-computer users to get into. As Guy Kewney wrote in Personal Computer World:

"For entirely inexplicable reasons, programming languages arouse strong emotions in their devotees' hearts. Each language attracts its band of followers and it sometimes seems that the more obscure or difficult or awkwardly-syntaxed the language, the more fanatical its proponents. BASIC in particular seems to anger more people than just about any other aspect of microcomputing, yet it has helped thousands of newcomers to get to grips with their machines, which would certainly not be the case were Pascal, say, or APL the most commonly-implemented languages on micros[23]".

Meanwhile, Gleadow reckoned the Commodore's new colour computer would be available "in every High Street" by the time the Proton launched, which turned out to be fairly accurate as the VIC-20 was freely available by the end of 1981, unlike the Proton.

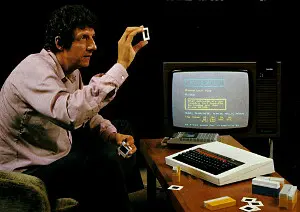

Paul Kriwaczek, Producer of the BBC's Computer Programme, © Popular Computing Weekly, 30th September 1982Acorn was also accused of rushing its prototype and then selling the finished machine at an unrealistically low price, an accusation that Chris Curry of Acorn admitted when the company had to put up the price of the BBC Micro almost immediately in the February of 1982.

Later there were also questions about why the BBC was even getting involved with selling micros in the first place, particularly after Acorn had struggled to ship its BBCs in time.

Your Computer had accurately prophesied this in its review of the micro in January 1982, when it suggested that because the BBC and Acorn had done their homework, they had produced a machine better than the market demanded, but that Acorn would probably not be able to meet the demand once word got around as to how good it was[24].

It wasn't only that "the failure of Acorn to satisfy delivery schedules [did] the BBC's reputation harm" but the fact that the BBC Micro all-but missed its debut and so had "virtually no part to play in [its] television series, The Computer Programme"[25].

Even the very suggestion that the BBC needed its own hands-on cheap computer was debunked by The Computer Programme's producer Paul Kriwaczek, who said that the TV programme was "designed to be independent of any computer".

"The original pricing structure has proved to be too optimistic"

Besides, the BBC Micro was certainly never cheap, rising quickly to £335 and then £400 - where it remained for several years - whilst Sinclair's 48K Spectrum - with 16K more memory than the BBC - weighed in at only £175.

When the price went up, the cut-off date was set at the 1st of February, with those having ordered before paying the "cheaper" price, and those after the new higher price.

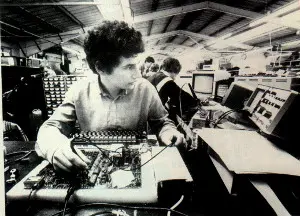

Testing BBC Micro motherboards at Race Electronics, Mid Glamorgan, © Personal Computer News 1983Chris Curry conceded that "The original pricing structure has proved to be too optimistic, given the need for particularly rigorous tests", although he also stated that Acorn thought it had now solved its chip problem with Ferranti and the 12,000-order backlog would be clear "by March"[26].

Meanwhile, In another attempt to justify its position, head of the BBC's Continuing Education department, Sheila Innes, suggested that the BBC "had to ensure [that] there was modular upwardly-expandable hardware on the market", despite that fact that Acorn's existing Atom was just as modular as the BBC Micro[27].

The Computer Programme

Chris Searle and a BBC Micro on the front cover of "The Computer Book", which accompanied the Computer Literacy Project. © BBC Publications, 1982The whole Computer Literacy Project was planned to include a 10-part television series presented by Ian "Mac" McNaught-Davis - former European head of Comshare and who had been suggested for the job by TV naturalist David Bellamy[28].

The series was initially set to be called First Byte, but was later renamed to the more prosaic The Computer Programme.

It was co-presented by Chris Searle, who was an easy choice as he had previous worked in the education department before moving on to co-present "That's Life".

Also included was a 30-hour course in programming BASIC, a load of application software - another source of controversy considered by some to be way outside the BBC's charter - and a discount of 50% for the first machine in each school, courtesy of the Department of Industry.

The timing of this government announcement was somewhat awkward as it now meant that Acorn effectively had two separate deadlines to produce its machine against - the BBC wanting the machine to be ready for its TV programmes, and the DoI which was also using the BBC Micro as a prize in one of its competitions.

Although the DoI scheme generated a significant amount of interest in the BBC Micro, it was also thought that it delayed the machine's launch by a couple of months[29]

This subsidy of micro purchases in schools continued throughout 1982 and when the Micros in Schools scheme finished there had been a 100% take-up of the offer amongst the secondary schools which had been targetted, so there really was a "micro in every school", whether or not that was actually useful.

The Vienna-born Kriwaczek had an unusual background for a TV producer, having exhibited as a painter at the Royal Society of Watercolourists as well as possessing the peculiar distinction of being the "only practicing dentist to [have] run a nightclub in Kabul".

That particular situation occured after qualifying in dentistry from London Hospital medical college and then doing a stint as a dentist in Afghanistan, where he happened to form a band with a friend plus a couple of Americans. Lacking a venue, they set up a nightclub at the Khyber Restaurant so they could have somewhere to play.

He returned to the UK in 1968 and joined the BBC as a script writer for the overseas radio service, before ending up in the Continuing Education department, a move which ultimately led to the Computer Programme.

According to Kriwaczek, planning for the series started around 1978, which would pre-date the 1979 screening of ITV's "The Mighty Micro" - a series based upon Christopher Evans' book of the same name and which is sometimes credited as "inspiring" the BBC's computer literacy efforts.

Thinking that the impact of microelectronics was going to be significant and that the BBC "really ought to be taking a major lead", the corporation produced a short series called "The Silicon Factor".

This was followed by "Managing the Micro" - a how-to series aimed at, er, managers, but in between the two series the market had altered dramatically with the introduction of cheap home micros like Sinclair's ZX80.

Kriwaczek was then asked to produce a new series explaining micros to the average person, so to help with research he bought a Nascom 2 in order to learn programming.

It was this experience which convinced Kriwaczek that the new series had to be more than "just another television series".

Although Kriwaczek was keen to stress that the BBC Micro was completely separate to the programme, it was also true that one necessitated the other. Advisers had already suggested that:

"It was absolutely necessary than an organisation with the standing and public confidence of the BBC should enter the business of computer software"

So once that had been established it seemed almost impossible for the BBC not to become involved in the hardware to run it on, and so it did, culminating in the decision in 1981 to award the contract to Acorn to produce its Proton microcomputer with the BBC name on it.

There was also evidence that helped to back up this viewpoint, as after a pilot episode of the programme had been shown to a few thousand viewers around the country, nearly 20% said that they would buy a microcomputer to go with it if it was about £200[30].

"The BBC Microcomputer is expensive, but it's still the best value for money on the market"

However, Kriwaczek recognised that Acorn's BBC Micro was not cheap - but then neither was a colour television or a stereo - but that he would have been:

"very reluctant for the BBC to sell something like the Sinclair because it is so limited. The Sinclair cannot be expanded; it is fundamentally a throw-away consumer product. The BBC Microcomputer is expensive, but it's still the best value for money on the market"[31].

Chalk and cheese: A plastic, rubber-keyed, small, light and essentially 'disposable' Sinclair ZX Spectrum sits on top of a metal-cased, full-size-keyboarded, expandable and solid BBC Model B microcomputer. From the author's own collection

Summarising the project, co-author of the Computer Book that was published along with the first series - Robin Bradbeer - said:

"We can see that the whole project 'grew like Topsy' and seemed at one stage to being to devour the original idea. It now seems to be under control and promises to be one of the major influences on computer awareness ever conceived[32]".

Kenneth Baker and the micros-in-schools scheme

There was no doubt that Acorn had been significantly helped not just by the timing of the BBC's decision to launch its computer literacy project, but also by the ongoing micros in schools scheme and its spin-offs - even though Your Computer reckoned that the Government had come along a little too late and whatever it did was unlikely to change the way the market was already developing.

One micro per school was "irrelevant" compared to Sinclair's monthly orders, market growth was already accelerating and there were already 250,000 personal computers in the UK[33].

The scheme had been set up by Kenneth Baker, an MP with a fairly conventional start in politics after graduating from Oxford University but who had - unusually for anyone in Government - actually experienced computers in business, in this case during the 1960s.

Baker then ended up in the Ted Heath Government where, amonst other things, he ran the Government's Computer Agency department and helped with a rescue of state-backed "big iron" monolith ICL in 1972.

This particular job was repeated in 1982, when Baker persuaded the Government that it was still worth saving the company - to the tune of £200 million in Government loans - when it ran off the rails again, instead of selling it off to a foreign buyer - a fate that ICL managed to avoid for another couple of decades, when it was finally sold to Fujitsu of Japan.

Kenneth Baker, Minister for Information Technology, © Your Computer, January 1982In a speech he gave in 1980[34], Baker outlined his 10-point "National Strategy for Information Technology", which included a demand that schools should be provided with cheap micros and software from British companies.

It also ended up effectively specifiying the brand-new role of Minister for Education Technology - a job that Baker filled in January 1981, as the first-ever such minister.

Shortly afterwards, Baker announced an agreement with the Government and "certain financial institutions" in the City of London to finance private projects involving microchip technology.

This came at about the same time as Baker was pledging to find more public money to finance the government's existing £55 million[35] Microprocessor Applications Project, or MAP.

This particular scheme was receiving applications at the rate of around 20 a month, so it was expected that the available money would run out by the end of the year. It was pointed out that although the budget seemed large, it was peanuts compared to the £200 million that had gone into part-nationalised ICL[36].

Meanwhile, Baker had been particularly critical of the Department for Education, which he believed hadn't been paying enough attention to "high technology". However he praised it when it supported his new Microcomputers in Secondary Schools (MISS) scheme, which was launched during 1981 and which had provided 2,000 secondary schools with a micro by the end of the year.

This was not however some massive state investment along the lines of the £1.1 billion injected by the Japanese Government into its computer industry in order to catch up with the Americans, but was more prosaic, largely because the Thatcher Government disliked direct state aid.

It would pay half the cost of a single computer for each Secondary school, as long as that school did not already have any computers.

Not everyone thought that this was a good idea, with commentators questioning the usefulness of just one or two computers in schools as far back as 1978. In an article in September's Personal Computer World, Mick Coleman suggested that even then:

"We stand at a turning point in the history of computing in Secondary education. We have passed through the eras of visiting data-processing departments to gape at tape drives clicking around, and of carrying suitcases of marked cards to a friendly company five miles down the road. What comes next is surely the personal computer in school and college".

Whilst agreeing that it was necessary to teach computing as it was to teach mathematics or the English language, it was pointed out that the expense of buying a computer didn't end with the acquisition of the machine itself but continued into software, maintenance and training.

It was even said that the possibility of these machines becoming idle through lack of software was only too real. He concluded:

"If computer science is to be adequately taught to a class, then facilities for a class must be available. It is inconceivable, for instance, that a woodwork class be equipped with only one saw, one chisel, etc.; it should be equally inconceivable that computing facilities be provided that are unsuitable for class use. For an in-house configuration, therefore, we are talking about either a multi-terminal system, or a system that can support a significant capability for the running of batch jobs. Ideally we are talking about a system that can provide both. Thus, what is educationally desirable is likely to be financially impracticable. Even if the money is made available, it must be questioned whether every school has the desire to run its own computer service, coping with the attendant problems of maintenance, documentation, advice, and so on[37]".

There were some alternative suggestions made as to how schools could implement computer science teching more effectively than having a single micro in the corner of the classroom hogged by only the most enthusiastic pupils, including the delightful idea of a Mobile Computer Unit. Coleman wrote:

"Vans, akin to those employed by mobile libraries, could be equipped with anything from a simple system to one comprising 20 or more computer terminals. Used in combination with a computing centre, this approach is highly attractive. Given that it is now possible to buy limited-facility microprocessor-based terminals - such as the Commodore PET - for less than £750, mobile units could be a highly cost-effective way of providing class teaching systems for school use".

Baker later went on to persuade the Government to make 1982 the "Information Technology Year", in a campaign which started in the summer of 1981 right in the heart of Whitehall, when he managed to persuade all 27 department heads to attend a four-day training course in information management at the London Business School.

"To believe that a thousand flowers will just pop up all by themselves without fertiliser, without the propagation of seeds, is a little naïve"

He subsequently managed to secure funds of some £80 million over the course of the next four years, with £1 million to back the IT year and promote "the convergence of computers, telecommunications and office equipment"[38].

Some commentators swiftly criticised IT '82 as having far too broad a remit, seeing as it covered everything from personal computers to satellites. Baker rejected this, saying

"There are many projects I have announced which I do not believe would have been possible to get off the ground without focussing attention on the whole of the information-technology area. Several of the projects I have announced would simply not have happened had I not done this ... I am doubtful if the schools scheme would have happened otherwise".

Baker continued by suggesting that the UK's Government was probably the only one in the world which had actually "pulled the threads together under one administrative head" and, somewhat poetically, that "To believe that a thousand flowers will just pop up all by themselves without fertiliser, without the propagation of seeds, is a little naïve"[39]

In May 1983, £3 million of extra funding to provide colour monitors and "control devices" like the BBC Buggy to secondary schools was announced, as well as £5 million to provide computer-controlled machine tools to colleges[40].

Additional funding to supplement the DoI Microcomputers in Secondary Schools (MISS) discount scheme was also announced by the Government.

Imaginatively called the Microcomputers in Primaries (MIP) scheme, it launched in the late summer of 1982 and was to be used to provide computers for an additional 27,000 primary schools.

The existing Microelectronics Education Programme (MEP) was similarly extended to provide teacher-training assisance.

By September of 1982, 20,000 schools had signed up and Acorn's arch-rival Sinclair had also been added to the "approved list", which also included Research Machines' 380Z.

Even then, there was a bit of perceived anti-Sinclair bias as the scheme only allowed the Spectrum to be purchased as a bundle together with an expensive, and largely superfluous, monitor.

Rival schemes

The rivalry with Sinclair was perhaps ironic, as Acorn - or at least Chris Curry - didn't actually see Sinclair as its primary threat, suggesting instead that Apple was much more its direct competitor.

Curry reckoned that Acorn had "a fairly wide base compared with Sinclair's monolithic, product-based approach, so we will never make such dramatic impact", a reference to why it might have been that Acorn seemed much more "under the radar" and anonymous in terms of overall press coverage. Curry continued:

"Clive brings out one product and pushes that straight to whatever sector of the market is appropriate. Generally speaking for him it is the consumer market. Whereas [Acorn] is a company with diverse interests, having customers in the consumer, development, education and office sectors"[41].

Chris Curry of Acorn, © Practical Computing, October 1982Despite Curry's dismissal of Sinclair even being in the education market, Sinclair did offer up its own £15 million scheme to try and get more ZX Spectrums in to schools instead of the BBC[42].

The company certainly had quite a fight on, as 80% of those schools taking up the various MISS/MIP/MEP schemes so far had gone for the BBC Micro.

In fact by November 1982, only three of the 422 applications made for the scheme so far had been for Sinclair's machine, with 97 for RM's 380Z and the remainder - 322 - being for Acorn's BBC.

Most Local Education Authorities (LEAs) had put guidelines in place indicating which of the three micros its schools could purchase[43], and of course many of them were standardising on machines they already had in their secondary schools, many of which had picked machines before Sinclair was even allowed as a choice.

"The Spectrum is just not up to the battering it will get in schools"

Derek Esterton of the Inner London Education Authority, which had picked RM after suggesting that "The Spectrum is just not up to the battering it will get in schools", said "We feel that standardisation is absolutely essential to enable us to provide any kind of sensible support for the schools".

Meanwhile, Hampshire and Manchester had gone for the BBC, where a Manchester LEA spokesman pointed out that "what we must buy must be compatible with as many machines as possible".

Arnewood School's SCOLA (Second Consortium Of Local Authorities) building, home of Commodore PETs around 1979There were still a few exceptions which could have been open to Sinclair, such as East Sussex which had standardised on Commodore PETs way back in 1978.

Authorities like Hampshire - which also had some PETs, at least at the Arnewood School in New Milton[44] - might have switched to Sinclair if it had been more suitable.

After an independent review of the available machines, a Mr. Bothwell of Hampshire's Education Office, who was clearly a Sinclair fan who had hoped that the decision would have gone the other way, reported:

"It is disappointing that several computer specialists who have recently evaluated the machine are less than enthusiastic about its performance and handling properties".

There were additional scathing comments about its keyboard, picture quality, graphics system and "idiosyncratic" version of BASIC.

Bothwell, who was either being diplomatic or really did want Sinclair's machine to have been more suitable, continued:

"it is therefore with considerable reluctance that the decision has been taken not to place orders with the DoI for this machine. Schools are strongly urged to consider cancelling unfulfilled orders for the Sinclair Spectrum which may have been placed in anticipation of a different decision"[45].

Whatever the outcome for Sinclair, by June 1983 15,000 primaries had a computer - an impressive jump from the 25 that had one in 1980[46].

The Government micros-in-to-schools programme was not without its detractors, as it had been pointed out that actually providing a single micro wasn't necessarily that useful in a school of 350 pupils, and so the scheme came across like propaganda as much as anything else.

There was then the issue of ensuring that teachers were trained enough to even able to use the things - a criticism levelled at the scheme by the National Union of Teachers, which said:

"there is little point in producing educational software if there aren't the teachers who know how to use it".

Software for Schools

Lack of software was also seen as a key issue, although MEP did eventually spawn several software companies[47].

One such was Five Ways, which targetted the standard triumvirate of Government-approved machines with a suite of educational software that was launched by publisher Heinemann in September of 1983.

Known as the The Dudley Programs, after the Midlands town where the software was first written and tested, the suite was aimed at the 8-12 age range and was written in collaboration with Dudley Primary School.

The whole suite weighed in at £185, or about £840 in 2026 and was launched at the Russell Hotel, where the Minister for Information Technology, Kenneth Baker - whose department had overseen the project to get computers in to schools in the first place - mentioned the world-beating success of MEP and referred to the "electronic generation being taught today"[48].

Five Ways Software showed that there were clearly at least some teachers who were trained enough and for whom MEP was working.

The company had started out with a minicomputer in the mathematics department of the King Edward's Five Ways School by "enthusiastic maths teacher" Tony Clements, before MEP funding allowed the employment of two full-time programmers.

The unit quickly expanded to two Portakabins on the playground and by September 1983 was up to 40 full-time staff in its own offices in Birmingham.

"At the moment we're streets ahead in terms of the quality of our software"

Five Ways was also after a piece of of its own world-beating success as it was looking to sell in to the US and Continental Europe. Clements suggested that:

"I think that Britain is soon going to be caught up in terms of the quality of its computer products. At the moment we're streets ahead in terms of the quality of our software , but very weak, I believe, in terms of marketing vigour"[49].

As well as commercial ventures, several user groups had sprouted up in the educational sector, including the Microcomputer Users in Secondary Education group, or MUSE, and the Educational ZX80/81 Users' Group, EZUG, which had been formed at Highgate School in Birmingham in December 1980 by Eric Deeson.

An advert for the educational user group MUSE, from Acorn User, January 1984

MUSE already had a library of some 100 educational programs, although these were mostly for the PET, Apple II and Research Machines' 380Z, and EZUG extended upon this by encouraging its members to write programs for the MUSE library, having received about 50 programs by the early spring of 1982.

The programs were reviewed by Eric Deeson of MUSE and up to two more independent assesors, however this was apparently an issue for some teachers, who Deeson suggested were "often somewhat frightened of submitting their own programs to outside scrutiny".

Sinclair was also doing its bit in trying to encourage "reluctant programmers" by setting up an award scheme for educational ZX81 software.

Deeson reckoned that this showed that Sinclair was "now aware of the education market" and that the company "is showing willing", although he also reckoned that it would be nice if Sinclair provided some money towards EZUG's printing costs.

In this case, judging was provided by Deeson and MUSE's software librarian Charles Sweeten, however it was perhaps a measure of Sinclair's modest expectations for ZX software in the educational market that the prizes amounted to only six ZX Printers, worth about £300 in total[50].

Criticism of the MEP scheme was addressed in part by the setting up of a small primary project team in September 1983 "to assess the needs of primary schools in both teacher training and resources", even though this only trained the trainers.

A spokesperson for the Department for Education and Science went on to defend MEP by saying "it's very easy to criticise the scheme, but no other country has done anything similar"[51].

Date created: 02 October 2013

Last updated: 13 February 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.