Acorn Advert - March 1984

From Personal Computer World

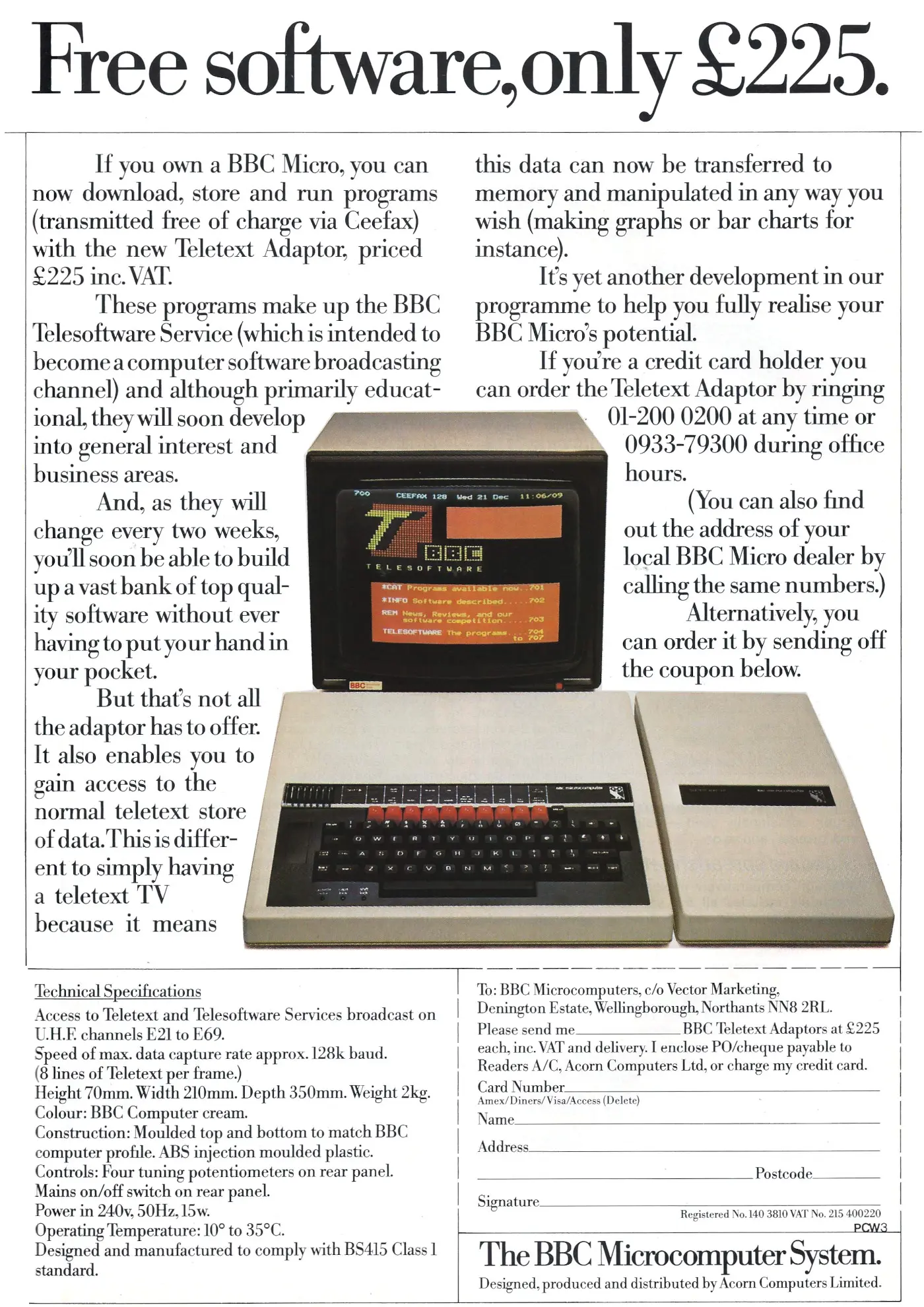

Free software, only £225

Looking much like its contemporary - the Prestel adapter - and with the same BBC Micro case-matching shape, Acorn's new Teletext adapter was perhaps better value as at least the content was free and didn't require expensive on-line call charges courtesy of BT.

Teletext for computers wasn't new, with adapters having been available since at least 1978[1], and it seemed like Acorn's had been in development since then too - it was meant to have been launched in June 1983, but the service was very late[2].

Vector Marketing, Acorn's distribution company, reckoned that some of the "several thousand" people who had already applied for the adaptor would finally get them at the end of September 1983 - some two years after it had first been announced.

Even then it was discovered that "one or two" of the units leaving manufacturer AB Electronics' factory were missing the software actually needed to download broadcast software directly[3]. By July 1983, Acorn had received 3,000 orders despite not having placed a single advert for the thing.

The BBC and Ceefax

The Ceefax editorial team update some content as seen in "The Computer Book" which accompanied the BBC's Computer Literacy Project, © BBC Publications, 1982The BBC's Ceefax service, of which the Telesoftware service became a part, was the first teletext service in the world when it launched on the 23rd September 1974.

It became very popular in the UK with its audiences peaking at 20 million a week during the 1990s, and it survived for nearly two decades of "the internet", finally closing down at the end of 2012 when the last analogue television service was shut down in the UK - a run of 38 years[4].

Initially developed to provide subtitles (closed captioning), teletext used spare lines in the broadcast stream known as the vertical blanking interval. Engineers discovered that whole pages of data (known as frames) could be stashed in this spare space which, according to the advert, gave a data rate of 128K baud.

This was pretty impressive at a time when modems were still mostly running at 300 baud. The BBC Micro was particularly suited to displaying teletext/Ceefax as its "Mode 7" graphics mode was essentially teletext, with the same graphics and ability to do double-height text. The adapter retailed for £225 - about £980 in 2026 prices.

Related to Viewdata - the system which became most famous as Prestel - Teletext (sometimes known as Broadcast Videotex) actually predated its more interactive cousin by several years.

Both the BBC and IBA (The Independent Broadcasting Authority) launched their services at around the same time, with the IBA's going by a contrived name of "Optional Reception of Announcements by Coded Line Electronics", or Oracle.

By January 1976, together with the Post Office, a joint standard was published with defined the overall standards the two services would use. Whilst the first public demonstration of true Viewdata had happened in 1975 when it was shown at Eurocomp, the technology didn't get going until the first wide-scale market trial in 1978[5], some four years after Ceefax commenced broadcasting.

In the same year, the BBC and the IBA were already testing out teletext as a technology for use in schools. Coordinated by Andrew Wallace of Brighton Polytechnic's Computing Centre, the trials initially used regular teletext in classrooms.

The conclusion of these early trials was that whilst some things worked well - simple animations of an oil well and a volcano were popular, and things like multiple-choice quizzes, where the answers could be shown by using the "reveal" option on the TV remote control, worked well - the thing that was missing was interactivity.

This led to abortive talk about adapting SWTPC's 6800 micro, after which the IBA's John Hedger built a bread-board prototype of a telesoftware receiver. This went forward as part of an application to the Labour government's micro fund, only to be dropped when Thatcher's conservative government came to power in 1979.

Project Director Michael Raggett recounted bitterly that "the £750,000 which we had been promised was turned into school milk or something".

Girls in computing

As a result of IBA perstering, the project finally got its money in 1980 and so could resume with a focus on interactivity.

Instead of plain teletext TVs, the team was using combined teletext/microcomputer/televisions built by Mullard at its Mitcham, Surrey, factory, with an interface that used only an infra-red remote, rather than an actual keyboard.

By the late summer of 1981, nine of these were out in the country at various schools, with a tenth at the lab at Brighton Poly. With such a relatively small number in the trial, Raggett was keen to describe it as "nine case studies rather than a sample"[6].

The team was also hoping that using teletext in classrooms as a general educational resource might help dispel the idea that computers were just for boys, as it was felt that the scramble of "sharp elbows and flying satchels" for one-on-one access to a micro, rather than democratic classroom-wide access to a big TV, meant that girls often considered computers as not worth bothering about.

That was certainly a problem in 1983, as revealed in a survey by research company Gowling Market Services, which showed that 80% of home computer users were a "father and son" partnership[7], and it's still a problem today with only 20% of women making up the 2025 computer science student body in the UK[8].

Meanwhile, by 1982, satellite and cable television was becoming a reality, which opened up the possibility of using entire spare TV channels for teletext, instead of the eight spare lines of TV signal as was currently the case - a situation which offered the tantalising possibility of two-way communications.

With interaction in mind, the EEC gave £50,000 to London-based Logica and Italian General Systems to investigate the possibilities, as well as the challenges of a cable-TV system[9].

The birth and death of telesoftware

One of the other existing "interactive" services that teletext offered, and which the Brighton trial had already dabbled in, was that of downloadable "telesoftware".

The first public demonstrations of this was at the Viewdata '80 exhibition, when the Post Office showed a program written in MicroCOBOL being downloaded and run by a DEC PDP-11/03.

By 1981 several bodies were working on standards for downloadable software, in particular the Council for Educational Technology (CET) which had been liasing with the Department for Industry, the Post Office, Commodore and Research Machines.

Publishers were also experimenting, with Prestel even offering 1,000 pages to Practical Computing's publisher IPC, specifically to "encourage telesoftware".

Practical Computing had already been dabbling with telesoftware for around a year, but the agreement and formal budget allowed the magazine to make use of a Research Machines 380Z in order to upload software to Prestel, to the CET standard.

This meant that it could also seek advice from CET, which had been working with RM on educational software along with teachers from Hertfordshire and the Advisory Unit For Computer-Based Education.

It was the humble ZX80 that seemed to reveal the potential of telesoftware, as an early trial of simple ZX80 software routines led to 60 downloads in two weeks - not a huge amount by modern standards, but significant because there were only 10,000 Prestel terminals at the time, and these were all assumed to be "business people".

Unfortunately, at the time, the RM 380Z was not licenced to use on the British Telecom network, so Practical Computing was considering uploading its new Prestel pages via a DEC PDP-11 TM-3 - the same machine that the first public demo of telesoftware was run on.

Practical Computing's software pages were launched in May 1981, although it was perhaps not telesoftware as it would come to be known - with automatical download and conversion to actual software - as users would be expected to manually copy the program from the screen[10].

In the summer of 1983, the BBC launched its official telesoftware service - the first in the world - which ran under Ceefax in a project that was coordinated by former teacher Lawson Brown and which was timed to coincide with the start of the 1983/1984 academic year.

The fact that the BBC Micro was well-suited to telesoftware was no accident, as it had been part of the original specifications agreed in a March 1980 meeting - which included the Department of Industry, the Council for Educational Technology, the National Computing Centre, local authorities and others - for what was at the time an unknown "BBC microcomputer" which was to be used for the BBC's upcoming Computer Literacy Project[11].

The final system, which also evolved out of the earlier trials undertaken with Brighton Polytechnic, and which continued in collaboration with valve-and-chip company Mullard as well as ITV, broadcast software at about 15 seconds per kilobyte, although this included error checking.

Software for broadcast came out of what was called the "sausage machine" - an encoder which, according to Brown, "takes an ordinary file - in tokenised BASIC - and turns it in to an ASCII file which is what Ceefax demands. Then it splits it up into Ceefax pages".

All the software was unencrypted as the "whole idea [was] that telesoftware should be provided as a public service", with much of it coming from the earlier MEP or Brighton Poly projects. It appeared under Page 700 and programs were changed every two weeks and repeated once after three months[12].

The service was officially launched in September 1983, but there were problems downloading some BASIC programs. The service was patched in early 1984 to fix the issue, which meant that any BBC BASIC program could be downloaded successfully.

There were also some improvements to the handling of tokenised BASIC, which helped with broadcast efficiency, and support for machine code was added for the first time, which widened the scope of available software significantly.

There were even rumours that the BBC was considering providing proper funding from its software profits[13].

Unfortunately, the idea of telesoftware didn't seem to survive for that long, as it was announced at the end of 1989 that the BBC was ceasing telesoftware broadcasts, with very little notice, and after much encouragement to buy teletext adapters.

Some spurious argument had been made about the current generation of teletext decoders in televisions having restricted capacity to hold pages - even though the raw hexadecimal of telesoftware would be meaningless to TV sets and so could be safely skipped - and how their presence made access time longer.

Personal Computer World responded to a letter published its October 1989 edition lamenting the death of the service by saying:

"it is amazing that, in the UK, there is little development of radio and TV-based data transmissions. In the US a mass of local radio stations use spare capacity to broadcast share prices, weather maps and computer data. Maybe there's not enough money to be made"[14].

Ceefax was also used to relay major developments in Acorn's Computer World Chess Championship semi-finals, held at the Great Eastern Hotel in London in December 1983.

The competition, which Acorn had sponsored to the tune of £40,000 (£182,700 in 2026), with an extra £20,000 going to the World Chess Federation[15], was being held in Britain for the first time in its history and featured the defeat of the exiled Victor Korchnoi by the 20-year-old Gary Kasparov.

It was also the first world-class tournament to feature reporting, commentary and analysis by computer, with an additional 12-station Econet network of BBC Micros set up to allow visitors to follow the play, with major developments in play being routed direct to Ceefax via a modem connected to another BBC Micro.

In January 1984, the victorious Kasparov went on to play against ten British teenagers simultaneously in Acorn's Covent Garden showroom, using a bank of ten BBC Micros running Acornsoft's computer chess game.

Two of the teenagers, selected by the British Chess Federation, actually beat Kasparov, although another - Susie Walker - fainted and had to retire, citing the persistent flicker of the 'prompt' square on the screen as the cause of her demise[16].

In the Autumn of 1984, a last-minute change in the law opened up possible commercial uses of teletext for the first time.

In an amendment to the Cable & Broadcasting Bill then going through Parliament, Home Office minister Douglas Hurd added a change that permitted the IBA to broadcast encoded or scrambled tranmissions that would require subscribers to hire dedicated decoding equipment.

Hurd explained that the IBA "was thinking of providing new information services to specialist occupation or professional groups such as doctors and farmers, on a subscription basis".

It was also reported that Britain was some five years ahead with its teletext technology, but that there was still a vast untapped potential. Sales and Marketing controller for Oracle, Humphrey Metzen, went to to say:

"the technology provides opportunities we had not even conceived when we first began transmitting teletext. We are now talking about a totally new medium... of which we still don't know the full potential"[17].

Off-the-wall telly software

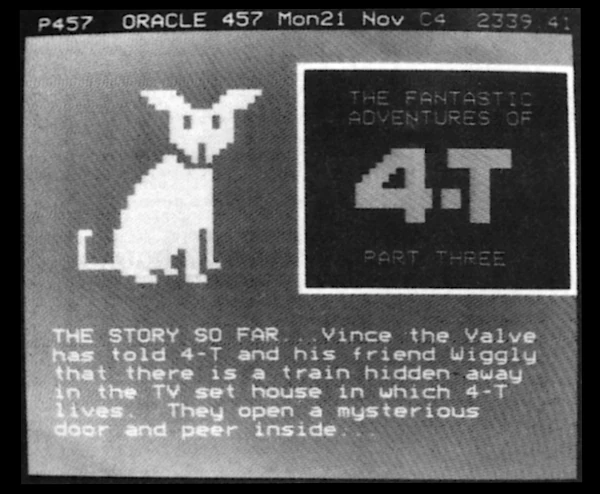

There were also some more off-the-wall uses of teletext. At the beginning of 1986, Channel 4 - the part-commercial part-public-service broadcaster that launched in November 1982 - sold its teletext cartoon serial, The Fantasic Adventures of 4-T, to a Swiss broadcaster.

The adventures of 4-T on Oracle's page 457, from Personal Computer World, February 19864-T's adventures, with pals Vince the Valve and Wiggly, had been running for three years on page 457 of 4-Tel, Channel 4's equivalent of Ceefax and Oracle.

Mort Smith of Intelfax, the publisher of 4-T, stated that the frame-based cartoon dog was "a major asset"[18].

Channel 4 also pioneered the unconventional use of "light-coded" on-air software transmission in its 1985 "4 Computer Buffs" program, broadcast on Monday nights.

Unlike Ceefax's telesoftware, which required expensive dedicated hardware decoders, C4's software could be picked up using a "simple-to-construct light pen", with a design for a DIY £5 version available from Mike Thorne of University College Cardiff.

Unfortunately, the overall technology - which encoded its data in a pulsing on-screen square in the corner of the TV picture - suffered from the slow scan rate of television, meaning it took about five minutes to download 1K of data[19].

4-Tel nevertheless also announced its own "proper" telesoftware downloading service in 1985, initially for the Spectrum but with a Commodore 64 version following shortly afterwards. Custom decoders would be available for the comparatively-bargain price of £140[20].

Teletext in the US

Teletext was also tried in the US, with early testing undertaken in the spring of 1979 by Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) on one of its stations, KMOX-TV in St. Louis.

The test compared the Ceefax/Oracle version of Teletext with the Antiope system used in France, however as there were no television sets in the US which could decode Teletext, the only "viewers" were CBS's own staff, using specially-equipped sets which it owned[21].

The year before that, KSL-TV of Salt Lake City, Utah, had also started tests of the BBC's version of Ceefax, in trials which commenced in June 1978. The two-year trial had been kicked off after Arch Madden - president of KSL's parent company - had visited the UK in 1976 and had seen Teletext in action.

The project, managed by KSL's director of engineering Bill Loveless, created Teletext receivers partly from standard hardware but also from homegrown equipment, using modified versions of the same Texas Instruments' TIFAX decoders as used in many of the UK's television sets.

However, like CBS, the only people who could see the transmissions were KSL's own staff, as regular non-experimental transmissions were forbidden until the technology received FCC approval[22].

Ultimately, Teletext in the US was considered to have been a colossal failure.

Around $90 million had been spent on the development of three experimental systems - Viewtron, KeyFax and Gateway - with only 5,000 subscribers in total to show for it.

However, this didn't seem to be be preventing the likes of IBM, AT&T, CBS, Bank of America and Sears from planning to enter the videotext market a few years later[23].

Date created: 04 November 2014

Last updated: 15 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.