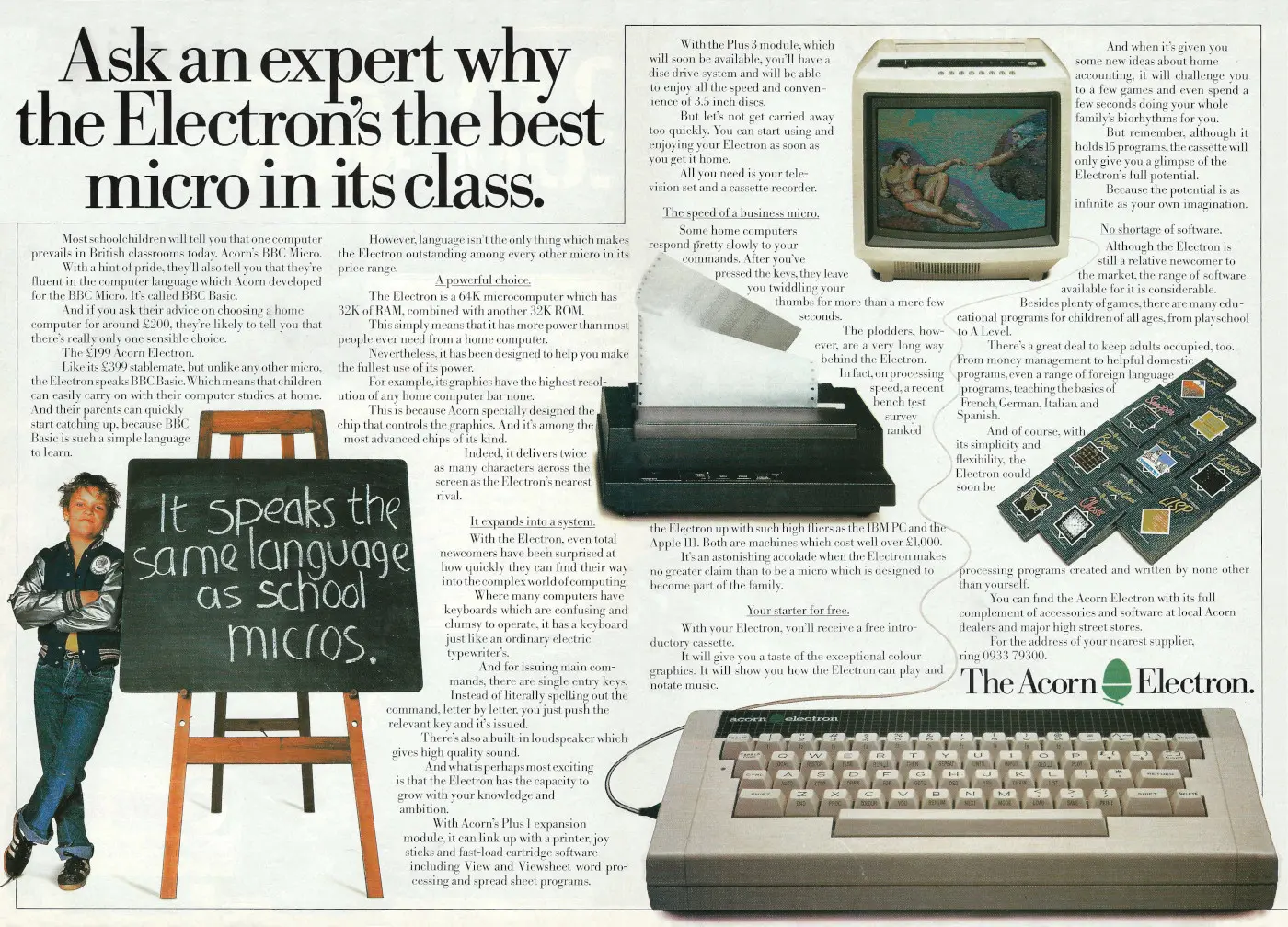

Acorn Advert - February 1985

From Your Computer

Ask an expert why the Electron's the best micro in its class

The Baron of Beef pub on Bridge Street in Cambridge, seen in 2015Here's another advert for the Acorn Electron, the cut-down version of the BBC Micro.

In common with many other Electron adverts, it stresses the fact that it's mostly the same as the expensive £400 BBC Micro, but is more affordable for home, retailing for half the price of the BBC - £199, or £800 in 2026 money.

This also appears to be the last Acorn advert that appeared in Your Computer in 1985 - the year which saw Acorn encounter some serious financial difficulties, coincidentally at about the same time as arch-rival Sinclair.

Rivalry between the two was still going strong, even to the extent that Clive Sinclair and Chris Curry had actually had a well-publicised punch-up in Shades Wine Bar in the centre of Cambridge, following their (separate) company parties at the Baron of Beef on the Friday before Christmas, 1984.

Sinclair had lashed out with a rolled-up copy of a magazine because he was "angry at Acorn's dishonest advertising", then grabbed Curry around the face who saw red and landed a mild punch back[1].

Sinclair apparently made up with Curry, who he'd recently referred to as "scum", the following year[2].

Brighton Bomb

Curry was perhaps lucky to have even made it to the Christmas party at all.

As a Conservative party member and a strong supporter of Margaret Thatcher, he had been invited to attend the Tories' annual conference in Brighton.

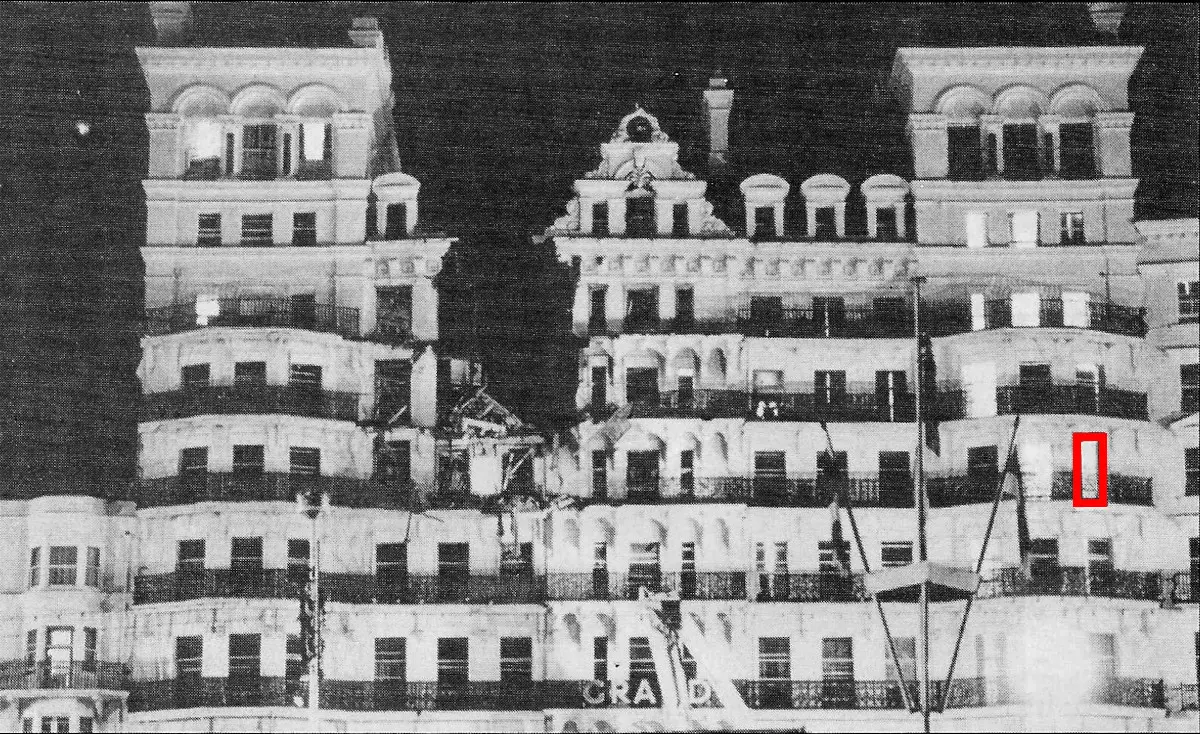

At 2.45am on October 12th 1984, an IRA bomb, planted behind a bath in room 629 of the Grand Hotel and intended to take out Thatcher, went off whilst Curry and various Conservative party members were still in the bar.

A photo of the Grand Hotel in Brighton after the explosion, with Chris Curry's room highlighted with a red box. From Acorn User, December 1984

The bomb demolished a significant part of the middle of the hotel and dust and debris piled in to the bar.

Curry returned to his room - 426 - and stayed there until being thrown out by the police and taken to Brighton police station to make a statement sometime later.

His luggage was picked up two days later by his London secretary Lesley de la Mare[3].

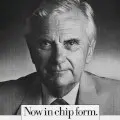

The perenially-sad-looking Chris Curry of Acorn, © Popular Computing Weekly, February 1985The Electron got off to a perilously slow start - by the autumn of 1984 Acorn had announced that a modest 130,000 Electrons had been delivered to dealers since the machine's launch the year before[4].

By the end of January 1985 Acorn was having to announce a major price cut for the machine from £199 to £129 - a situation precipitated at least in part by the arrival of Sinclair's Spectrum Plus.

However, the company was still stubbornly refusing to discount the BBC Micro, which was still at £400, although it was offering a token trade-in scheme with £50 off.

This was partly contractual, as the agreement with the BBC limited any price-cutting potential, but also philosophical, with Curry having stated in 1982 that:

"If we need to go to a lower price we bring out a new product that costs us less, we don't cut prices"[5].

Clearly, this wasn't enough for the likes of WH Smith and Boots, both of which were already discounting the BBC to around £340, whilst Acorn was dogmatically stating:

"The non-reduction stands at the moment - we believe the machine is still commercially viable at £399. The £50 trade-in is an extra incentive. A substantial number of people buy BBCs as upgrades from other computers".

Acorn's Chris Curry also took a pot-shot at Sinclair, suggesting that:

"The QL with a so-called 32-bit chip, for example, made no difference to our BBC sales".

Chris Curry seemed to be somewhat camera shy and his photos didn't appear that often in the press, and when they did he often looked thoroughly unhappy about it.

However, according to "Chip Chat" in Personal Computer World, he did possess an unusual sense of humour.

Apparently during his 38th birthday party, back in 1984, dinner was accompanied by ghost noises, slime oozing through the floorboards and collapsing curtains.

It was said however that Curry's original plans for his bash had included a squad of SAS-style paratroopers "bursting in through the windows"[6].

A dark week for Acorn

Meanwhile, early signs of serious financial wobbles were appearing, as Acorn's share price on the USM had dropped to 43p, with a brief recovery after the announcement of the Electron price-cut, followed by a return to 44p.

There were also rumours that Acorn had had poor Christmas sales despite its £3.5 million Christmas advertising blitz, which Curry denied, claiming that it had shifted 100,000 each of the BBC and the Electron - even though it had been forecasting combined sales of 300,000.

The denial came at a hastily-convened press conference held on the 22nd January, where Chris Curry blamed the speculation over Acorn's Christmas sales directly for the company's current problems.

However, Popular Computing Weekly pointed out that the real reason for the fall in Acorn's star was down to its total lack of serious replacement for the ageing BBC Micro, questions about which eventually led to Chris Curry and Hermann Hauser revealing that there was indeed a replacement machine planned, which Hauser even went as far as to suggest was:

"As radical a machine in its time as the BBC when it was launched".

In a way, being forced to admit this was not in Acorn's best interests, as it wasn't really going to help sales of the overpriced BBC Micro[7].

However, Acorn at least had some friends left, as high-street retailer Laskys defended the BBC, with the company's Mike Taylor suggesting that:

"The BBC has sold very well, considering that at £399 it is at the top end of the home computer range".

At the time, Acorn was also having to deal with the end of the government's Micros in Schools scheme, which had left it with about 74% of the school's market, and was considering its own imaginitively-named Acorn Micros in Schools scheme.[8].

Acorn's dominance of the UK education market was perhaps ironic, as a few years before Chris Curry had suggested that the Department of Industry's scheme hadn't actually helped Acorn that much. Responding to the requirement that the micros under the scheme had to be British, Curry said:

"I am a free-market person and absolutely against all forms of protectionism. The Americans practice it against UK products, so I suppose it is only fair that there is a little bit done here. But is it beneficial? The education market for us has been quite a small proportion of our business; so far it hasn't made a lot of difference"[9].

Italian typewriters - a brief history of Olivetti

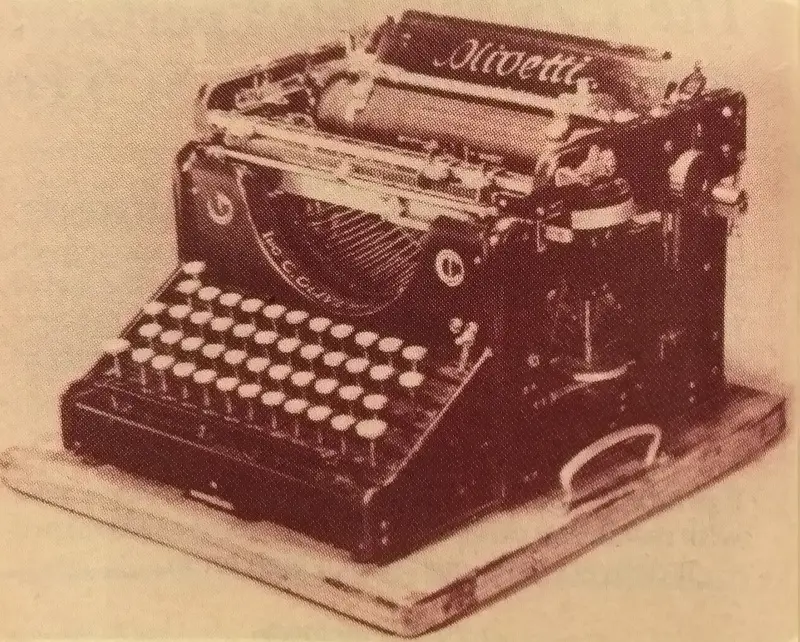

Olivetti's M1 typewriter from 1910, © Practical Computing January 1989Meanwhile, Olivetti of Italy was on the lookout for strategic alliances it could form, or for smaller companies it could buy, in order to help it compete against what it saw as "American and Japanese giants", as chief executive Carlo di Benedetti had become convinced that Olivetti was just too small to survive by itself.

Olivetti had been started as a typewriter business, based in the north-Italian town of Ivrea, near Turin, by Camillo Olivetti in October 1908.

With 350,000 Lire in start-up capital and recently-acquired knowledge of American business methods and industrial design, the company sold its first typewriter - the M1 - in 1910.

By 1929, the company was shifting 13,000 machines a year to markets in Europe and Argentina, and by the 1930s it had diversified into office equipment.

In 1959 Olivetti announced its first home-grown mainframe computer - the Elea 9000 - but withdrew from the cut-throat mainframe business by the mid 1960s.

Financial problems caused by the large sums of money required to stay in the data-processing business led to a rescue of the company by a consortium of banks and other Italian business.

This bought in Bruno Visentini as chairman, along with the decision to stop chasing Sperry, Burroughs and IBM.

Instead, the company moved on to calculators, like its Programma 101, although it kept a small presence in the minicomputer business, selling its P6060 and P6040 systems.

By 1978, it employed 62,000 people and had a turnover of 1,550 billion Lire.

Carlo di Benedetti of Olivetti, © Practical Computing January 1989Olivetti then ran into more financial problems which led to a rescue by well-known Italian entrepreneurs Carlo and Franco di Benedetti.

As well as injecting cash to prop up the business, the pair slashed the headcount, which fell to just over 17,000 by 1988.

This was coupled with a new aim to make Olivetti "a world leader in the emerging information technology revolution", which was followed up by the release of the M20 personal computer in 1982.

Whilst this micro was advanced in some ways, what with its 16-bit Zilog Z8000, it wasn't IBM compatible, but Olivetti had seen where the market was really going - IBM compatibility but with better performance or price.

To target this market, Olivetti swiftly released a successful follow-up in the M24 - the name reflecting an ongoing and nostalgic naming scheme that started with its M1 typewriter in 1910.

However, it was the first of Olivetti's wordwide partnerships - with AT&T in the US - that made the M24 a top seller.

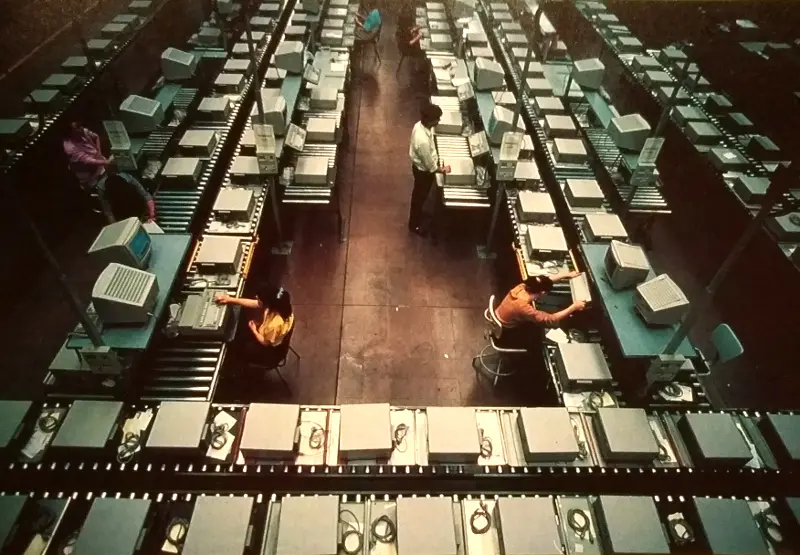

Olivetti's production line at Ivrea, near Turin, © Practical Computing January 1989The two companies came to an agreement where Olivetti would sell AT&T's minicomputers in Europe and the rest of the world outside North America, whilst AT&T would sell Olivetti's micros into the US.

AT&T took a 25% stake in the Italian company, with an option for up to 40% after five years, and shifted 200,000 of Olivetti's M24 in 1986 alone.

The agreement quickly ran into trouble though, as there was a feeling that Olivetti wasn't pulling its weight - it had sold only 10,000 of the American company's 3B minicomputers, whilst AT&T had sold 500,000 Olivetti micros by the end of 1988.

However, AT&T only sold 40,000 machines in 1987, with poor sales not being helped by the fact that the M24 was getting long in the tooth whilst the competition had moved on.

Nor did it help the partnership when Olivetti started selling its own LSX 3000 range of minis, or that Olivetti was very late to the 80386 party, being the last major manufacturer to come out with a micro based on Intel's shiniest new processor, months after the competition.

Things came to head in April 1988 when it was rumoured that AT&T was going to exercise its option to buy 40% of Olivetti and perhaps take a controlling share.

This didn't happen - maybe because Benedetti had threatened to sell his 14% stake and take the rest of the board with him - but speculation remained that AT&T might check out completely.

However, the looming creation of the Single European Market in 1992 was not far away, and it as thought that AT&T would really not want to lose access to that huge market, so it was forced to stay sweet with what remained not just one of Europe's biggest computer companies, but just about the only European-controlled "major player in the microcomputer industry"[10].

Olivetti buys Acorn

Despite the difficulties with AT&T, which was having its own problems which would lead it to undertake the largest single lay-off in US corporate history towards the end of 1985 as it shed 24,000 jobs following the merging of two of its divisions[11], Olivetti was still looking for more partners or companies it could buy on the cheap and turn around, especially in Europe.

To this end, it bought the fading office equipment and sometime micro producer Triumph-Adler, primarily for its large and established dealer network in West Germany.

It then ended up bailing Acorn out in February to the tune of £10.9 million[12] - which was roughly equivalent to the loss Acorn reported for the year-end 1984 - as well as assuming £47.7 million (£200 million) of other debt.

The final trigger had been the disastrous Christmas of 1984, which heralded what came to be seen as the collapse of the home computer market.

Unfortunately for Acorn, this came at a time when the company appeared to have finally solved a problem which had plagued it since its beginning: volume production.

Even worse, the 250,000 now-unwanted Electrons the company had committed to for Christmas mostly didn't arrive until the beginning of the following year, meaning Acorn was in real trouble. As Hermann Hauser said in an interview with Personal Computer World in May 1993:

"We had them coming in by the lorry load, just at the time when the market collapsed, and of course the one thing we'd never had to do was turn the tap off".

Olivetti's appointing of Alex Reid as Chairman, over the heads of Curry and Hauser, was followed up in June by the appointment of its own emergency managing director in the form of Alex Uboldi[13], one of Olivetti's current senior directors and a man who had made his name as a high-flying IBM troubleshooter[14].

Dr. Alex Reid, © Popular Computing Weekly, March 1985Barely a week after the buy-out/bail-out, things got a lot worse for Acorn when it was forced to suspend its shares on the Unlisted Securities Market after they had dropped to only 23p.

Speculation about the future of Acorn was running rife following the appointment of Dr. Alex Reid to oversee the day-to-day running of the company.

Acorn had also unsettled the financial markets by sacking its financial advisers, Lazards, because they were proposing a reorganisation of the business that would see founders Curry and Hauser lose control, and then its own stockbrokers, Cazenove, resigned.

After its shares were suspended, the company announced that Close Brothers was to replace Lazards as advisers, and it issued a statement that it was "actively taking steps to reorganise the company's affairs".

The Financial Times reported that doubts about Acorn had been growing thanks to its over-reliance on the old BBC Micro and weak sales of the Electron, which Acorn had already conceded had been disappointing at its January press conference.

The conference had been hastily arranged in order to deflect rumours of poor overall sales in the crucial pre-Christmas 1984 period.

The overall mood wasn't much helped by reports that the company was also looking to make about 30 employees redundant - the first time this had ever happened - at its Cambridge offices, whilst Amstrad and Sinclair were stirring things up by stating that after the Electron's price had been cut to £130, the machine was selling at below cost.

In typical Acorn style, managing director Chris Curry retorted that Acorn would be launching a more expensive version of the BBC Micro later in the year[15].

To round the week of turmoil off, the company also announced that it had cut the number of distributors from 17 to six and that it was no longer planning on buying Torch Computers.

The effect on Acorn's value had been drastic - in 1984 the company had been valued at £216 million, but by the middle of February 1985, after the crisis, it was down to only £31 million.

Forecasts of Acorn's performance during 1985 were also radically revised, with stockbrokers Wood Mackenzie suggesting a change from its previous forecast of a profit of £8 million down to a loss of £3 million, caused in part by the down-valuing of Acorn's huge stock of Electrons, thanks to the £70 price cut[16].

The price cut also hit dealers hard, and combined with Acorn's financial troubles made them even more anxious to shift their existing supplies of Acorn machines, as well as doubly-nervous about taking on any more Acorn stock.

Acorn wasn't alone in this new price war, as other companies were also in the process of burning their dealers, with Commodore managing the double (after the 64) by suddenly dropping the price of the Plus/4 by more than a half, whilst Sinclair slashed the price of the Spectrum Plus without warning.

The issue for smaller retailers was that by May 1985 they could buy their machines from High Street chains like Boots, Currys or Rumbelows for less than they could from their own wholesalers, even though it was some five months since alleged pre-Christmas overstocking had originally triggered the first price cuts.

With independent retailers starting to go broke, James Lucy wrote in Popular Computing Weekly during May:

"Quite soon the expert advice available from independents will be hard to find - the customer will have to rely on the pimply youth in Boots. Computers will become another routine consumer item, selling on brand name and marketing muscle with technical details relegated to a small appendix in the back of the instructions"[17].

Whilst the future for Alan Sugar's famous lorry driver "looked rosy", that of Sinclair's hobbyist demographic looked anything but.

Acorn stops advertising

A few months later, Acorn's PR firm Quentin Bell threw in the towel on the Acorn advertising gig, apparently as it had nothing to publicise - a suggestion that certainly seemed to be backed up by the apparent drying-up of advertising around this time.

Acorn seemed to be having ongoing problems with its PR and advertising agencies, as the next company to take on the job after Quentin Bell - Aspect - also gave up, announcing that it had "fired" Acorn because the company was apparently "reconsidering all its options, including its existing advertising arrangements".

The ad agency, in an unusually-public statement, issued as a press release which said:

"we feel extremely insulted that having stood by the company both financially and morally over the last seven, very traumatic months, they would like us to resubmit ourselves for consideration"[18].

By around June 1985, Acorn's share price had fallen to only 9p and there were rumours about Chris Curry's disaffection with the company.

The price of 9p was only 1p above that of Acorn's earlier Rights issue, however even after this partial floation the company still owed £3.4 million to its creditors.

The banks and Acorn's suppliers were apparently "being patient", but Acorn itself didn't seem too fussed about clawing its way back with a new line-up of micros or anything.

Back in March, Dr. Alex Reid "seemed to be offering more of the same", with a vague reference to an improved BBC "later in the year[19].

Elserino Piol of Olivetti, © Personal Computer World September 1988When Olivetti first bailed Acorn out in February of 1985, Personal Computer News reacted by suggesting that Acorn was pulling out of the home computer market entirely, citing a company statement which spoke of the need to "further reduce Acorn's dependence on the volatile home computer market".

It was thought that whilst the Electron would be canned competely - thanks to its poor Christmas 1984 performance - the BBC Micro would revert to its previous specialist educational status, with Olivetti's Elserino Piol, who was in charge of corporate strategy, wanting to make the BBC the world's leading educational micro, whilst also suggesting that the education market currently lacked a leader, which Piol said "could be Acorn".

Meanwhile, when asked whether it saw any issue in its name being attached to an Italian-owned micro, the BBC said that it was "entirely satisfied" with the agreement between Acorn and Olivetti.

However, other manufacturers, especially those with an eye on the BBC Micro's place in UK education, considered this situation to be "untenable". ACT's Roger Foster said:

"We will certainly be getting in touch with the BBC to suggest, politely, that the time has come for a change".

Olivetti was clearly aware of this issue, as Piol was keen to point out that:

"On the English market, where it has high profile, Acorn will be fully independent and will operate in parallel with British Olivetti. We shall act as an amplifier on the other markets particularly in the education sector"[20].

Acorn mirrored this sentiment as it didn't see the Olivetti connection as particularly relevant to the consumer part of Acorn's business, although Dr. Reid was keen to quash rumours of the imminent demise of the Electron, saying:

"We have no intention whatsoever of withdrawing from the home computer market, [and] nor does Olivetti".

Personal Computer News pointed out that it was easy for Olivetti to say that it wasn't withdrawing from the home micro market because it wasn't actually in it.

Reid sought to sooth concern over Olivetti's influence in Acorn by stating that the relationship with the new parent company would be "an arm's length one"[21].

Whilst the Olivetti connection was being downplayed, it was hoped that the Italian connection might prove useful, as by the late summer of 1988, Elserino Piol had become the chairman of Acorn.

Whilst then-current managing director Harvey Coleman suggested that Acorn was "known around the world for its outstanding technical capability" and that the company had "strengthened its position as the leading supplier of computers to the UK education system", he also hadn't suggested that Acorn had improved its marketing.

It was therefore hoped that Piol's good American connections might give Acorn a way back in to the US market which had almost ruined it[22].

Brian Long, new managing director of Acorn. © Acorn User, November 1985Back in 1985, there was another cash injection from Olivetti in the last week of July which, through a complex financial restructuring operation saved Acorn from liquidation - a situation which had been a real possibility since Acorn's share price, which had recovered after the previous bail-out, was back down to 11p shortly before shares were suspended for the second time.

The company was awash with debt, turnover had more than halved from £54.9 million in the six months to December 1984 to £22.89 million, and the company announced a £20.58 million loss for the year to June 30th[23].

The new cash took Olivetti's shareholding up to 79.8% - reducing the proportion of Acorn in public ownership from 10% to 6% - and effectively completed the take-over as a fait accompli.

At least this meant that the threatened sell-off of Acornsoft and Acorn Video, as well as fellow Acorn Computer Group subsidiaries Torus Systems - a networking company founded by Steve Ives and Steve Jolley which Acorn had a 25% stake in - and IQ Bio[24], in order to raise cash following the apparent failure of Olivetti's first-round cash injection, was no longer necessary.

Another positive side-effect of the Olivetti deal was that Acornsoft found itself free of its exclusivity commitment to produce only software for Acorn's own machines, at which point it immediately expressed its intention to produce titles for other micros. Elite, for example, soon found its way on to most of the other popular home micros of the day.

The BBC had also waived £2 million in unpaid royalties and other creditors were left with £7.9 million in bad debts, with Acorn's largest creditor - its manufacturer AB Electronics - particular badly hit.

With an understated style, AB's managing director Henry Kroch suggested:

"There have been some difficulties at Acorn and its performance has been disappointing. Olivetti taking a stake was only one step. The next state is to reorganise the management and then inject more cash".

Chairman and acting managing director Alex Reid said of the situation:

"At a creditors' meeting we put to the creditors a projection of the penny-in-the-pound [1%] rate they would get under receivership. Acorn would have gone in to receivership if any of the parties had not gone along with this deal. Acorn is now stripped of the problems of the past - we now simply have the problems of the present and the future"[25].

By the end of August, trading started again in Acorn shares when the company re-appeared on the Unlisted Securities Market at the princely sum of 2½p.

Shares closed at 6p by the end of the first day and were up to 14½p a week later[26].

It was also announced that Brian Long, from the Canada Development Investment Corporation and recently from Canadian tractor company Massey Ferguson, was shortly to become Acorn's new managing director, replacing Dr Reid, the former BT senior executive, in that capacity.

Reid also resigned as chairman whilst Alessandro "Alex" Uboldi - who blamed the situation on a sales drop between April and June that was more than the 40% forecast - would stay on to help out, taking on the role of chairman in the process.

Curry and Hauser also resigned as deputy chairmen but kept their seats on the board whilst Olivetti added to its grip with the appointment of Bruno Soggiu to the board and as a non-executive director[27].

Acorn downsizes, and a shot in the ARM

Acorn had also downsized from 451 employees in February to 275 employees by September. Co-founder Hermann Hauser, who had also seen his and co-founder Chris Curry's joint shareholding drop to a modest 14.5%, said:

"It is sad to see we had to reduce our overheads in the way we did. It has been a very sobering experience to fly very high one year and very low the next"

Despite the turmoil, Acorn did nevertheless manage to release the first details of what would become its most significant legacy: the Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) chip[28] that would lead to the creation of Acorn RISC Machines, otherwise known as ARM.

The RISC project - headed by Steve Furber on the hardware side and Sophie Wilson on software - was influenced as much by the simplicity and the unrivalled speed of interrupt handling and almost-RISC-like nature of Chuck Peddle's 1975-designed 6502 as it was by other RISC research at Berkeley in the US.

This was so much so that Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World considered the ARM as a natural upgrade to the 6502, writing that Sophie Wilson was described by her peers as "probably the world's best 6502 programmer" and that she designed the ARM accordingly to "suit herself"[29].

Acorn's RISC chip research - which had been partly triggered by a refusal from Intel to licence the core of its 80286 processor - had been undertaken in association with Californian firm VLSI Technologies Inc (VTI), which supplied the CAD workstations and fabricated the chips[30].

VTI also provided a team of engineers which joined Acorn following its first re-shuffle in February 1985, so the project was not something that Olivetti could easily renegue on even if it wanted to.

Acorn claimed a world first on the production of a RISC chip at the end of August, with prototypes of the chip able to handle 3 million instructions per second (3MIPS), but it was quick to point out that it hadn't invented RISC and that RISC itself was nothing new.

Marketing analyst at Acorn's Business division Mark Carrington readily acknowledged that:

"Research into RISC architecture has been going on at Stanford and Berkeley Universities and also IBM's Yorktown Heights research centre in the US".

The plan was to develop the chip further in house before using it in an actual micro, where it had even been speculated that it could be used in the recently-launched Cambridge Workstation, a 32-bit scientific machine based on much of the technology of the oft-rumoured-but-still-unproduced ABC micros.

Carrington was very much "no comment" about that[31].

Meanwhile, the ARM chip, which at £40 could comfortably out-perform the £300 Motorola 68020, had caught the eye of several other manufacturers, including Atari, IBM and Apple - which later on became a significant investor, and which would use ARM chips in its Newton handheld device[32].

At this point, ARM was spun off as an independent business unit called Advanced RISC Manufacturers, with Acorn retaining a 25% stake in the company and with Apple as the other major shareholder.

According to an Open Univeristy report on the Cambridge High-Tech Cluster, published in 2001, Acorn’s stake in ARM was worth more in the stock market than Acorn itself by 1999[33].

Meanwhile, each of the interested companies already had evaluation systems available, but the one thing holding them back seemed to be the lack of a second-source manufacturer, with VTI currently remaining the only supplier of the revolutionary chip anywhere[34].

In the same week as Olivetti's second bail out, the third official Acorn User Exhibition took place at the Barbican in London.

Acorn still managed to put in a showing with its "dreaded" BBC B Plus and also previewed its long-awaited 32016 second processor unit, which turned the BBC B Plus in to a 256K 32-bit machine for "scientific and research uses", albeit with a four-figure price.

It was expected that the second processor would be launched at the end of August along with the delayed Cambridge workstation[35] - essentially the ABC 210 but with a larger 20MB hard disk[36].

Time for a change

Even though founders Curry and Hauser no doubt felt stitched up by Olivetti when it announced in the spring of 1985 that it had effectively taken control of the company with 49.3% of the company and an option for 50.1%, external observers seemed to be of the opinion that the time had come for Acorn to pass to "more effective decision makers".

The rumour had even been that Acorn's financial controller Peter Wynn was not even authorised to sign company cheques and an ex-executive had stated that "if Chris and Hermann couldn't agree on a thing, it didn't happen. Nobody else had a say".

It had also been said that Curry was still trying to run the company as if it still had 35 people in it, with comments as far back as 1983 like:

"if only Chris Curry would get off people's backs and let them get on with the jobs he gave them, and stop fiddling with everything, things might move a lot smoother"[37].

An indication of how big and unwieldy Acorn had become and how it was simply impractical for just two people to run it was perhaps that under Olivetti the company was being split in to no fewer than four operating divisions.

Education and Training would be run by Jim Merriman, Scientific and Technical - to include the new ABC range - would be under Unix expert Jeff Tansley, Business would be under John Horton and the division that contained the BBC Micro and its new versions - Consumer Products - was now under Peter O'Keefe.[38].

In November 1985, it was revealed that founders Curry and Hauser had sold 50,000 Acorn shares between them - presumably some of their more-valuable-than-the-public ones - netting around £1.5 million each.

An Acorn spokesman was quick to scotch rumours that this meant the two were about to leave, saying "It is only a small proportion of their total shareholding", which remained at around 14%.

He continued "I doubt they would sell out completely at the current share price".

News of the sale didn't help Acorn's stock price, which closed down 13p on the previous week to 48p per share, although that was still a significant improvement on the 2½p that Acorn's shares were trading at when it was re-listed on the USM a few months before.

The BBC+ appears

Whilst the Electron eventually did OK, the original BBC Micro was in need of an update, not least as whilst its 32K might have been good in 1981, 1985 was the year of 128K micro. So, in May 1985, Acorn released the BBC Plus.

It wasn't actually much of an upgrade, although at least it had 64K on board and included the disk filing system (DFS) which was previously an additional add-on, thanks to a free slot made available by combining the operating system and BASIC together on to a single 32K ROM.

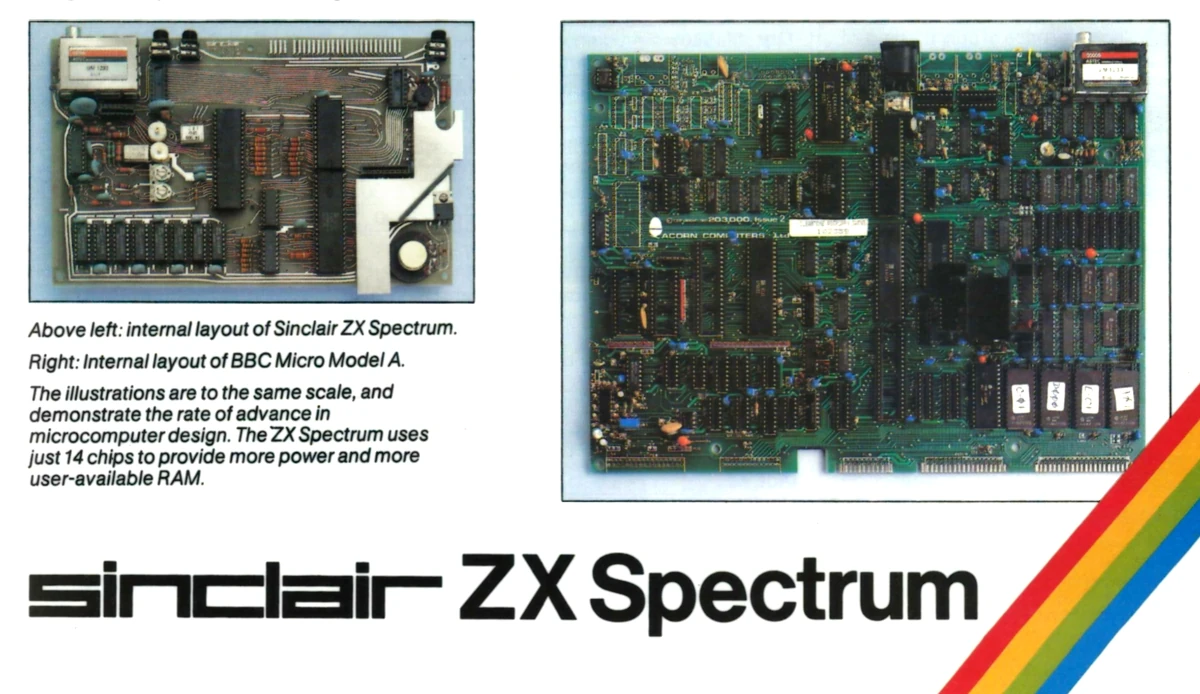

Unfortunately, Acorn seemed to have done little else to simplify the main circuit board, which was one of the easiest ways to reduce costs, a fact Sinclair knew very well and which had allowed its 4-chip ZX81 and 14-chip ZX Spectrum to be sold for so little.

Sinclair even used the difference between its 14-chip Spectrum and the original BBC Micro's much more complicated design as part of its own advertising, with this forming part of a four-page spread in October 1982's Your Computer. Despite having what Clive Sinclair would have called 'design elegance', it's notable that the Spectrum motherboard somehow manages to look far more like a DIY electronics project than the BBC board.

The Acorn ABC 310 - a re-packaged BBC Micro with a couple of 16-bit processors added, © Acorn User, October 1984It was thought that the Plus's board was a butchered version of the as-yet unreleased Acorn Business Computer (ABC), which itself was a re-packaged BBC Micro aimed at the business market, but either way its complexity did little to help the retail price - a "ludicrously" high £500 (£2,010 in 2026), which was twice the price of Commodore's 64.

Acorn was claiming to pitch the Plus as an "independents" machine, but was prepared for one or more of the big chains turning it down.

Although some dealers ordered it, at least one was reported to have been "dreading" the Plus's arrival[39], which was perhaps not surprising given the big chains' track record at selling expensive business machines[40]. An Acorn spokesman stated:

"The High Street is still making decisions over whether or not to carry the machine. After all, it is intended for the professional home market and for educational and small business use rather than as a hacker's machine".

Meanwhile, Peter Frost of Boots the Chemist was definitely in the "no" camp, saying:

"We are not taking the BBC B + at the moment. At £499, it is not really viable for Boots' range. We are, however, continuing to stock the BBC B with disc interface at £399".

Dixon's, Lasky's and WH Smith were also still undecided[41].

"As overpriced as any previous Acorn product - just who is going to pay that for a 64K micro?" was the conclusion of Popular Computing Weekly, which went on to suggest that despite the shock news of Acorn's takeover by Olivetti things were going on at Acorn just as they always had, with the £500 price tag for the BBC+ being unfavourably compared to the £170 for Atari's 130XE - a machine with the same processor and twice the RAM.

It was also disappointed that the high price also effectively ruled out a price cut for the original BBC B, which itself had long been considered overpriced at £400.

Popular Computing Weekly even suggested that the move heralded the end of Acorn as a serious force in the home computer business, concluding that:

"Either Olivetti shows the same understanding of the home market as the 'old' Acorn, or the company is deliberately attempting to pull Acorn out of the dangerously volatile home computer arena"[42].

The price was also called in to question because the cost of memory had fallen so much since the BBC Model B's debut in 1981.

Then, it was said that the 1K memory in the £70 ZX81 was a major part of its production cost, when a 16K RAM pack at the time cost £50, or about £200 in 2026.

By 1985 a 64 kilobit RAM module cost less than £1, with four of these being required to make up 32K memory.

The 1983 chip famine had helped, as computer makers had over-ordered to ensure supply and then cancelled as soon as they had enough chips, leading to surpluses and a crash in prices.

In addition, companies like Samsung were pushing into the market, with the South Korean chaebol already having spent $300 million (nearly £880 billion in 2026 money) in the previous year to increase its output of 64 kilobit RAMs to six million units a month and was planning an additional investment of $750 million over the next five years[43].

LaserDiscs and a modern Domesday Book

A BBC Master with the Domesday LaserDisc system at the Centre for Computing History, CambridgeElsewhere, Acorn was investing in the new "laserdisc" technology, in particular joining forces with the BBC and Phillips - inventors of the CD - to develop the technology to store computer data and software.

There was much interest in this as the LaserDisc system, with its huge 12" discs, could store 1 gigabyte of data per side - nearly a thousand times more than the standard floppy disc of the day.

The project to develop and licence the "laser disc ROM" as a world standard coincided with the BBC's Domesday Project[44], which was an attempt to "give the British people a chance to write a modern, video disc version of William the Conqueror's Domesday survey of 1086".

The new survey was expected to take two years to complete, with its 500,000 text pages, 10,000 Ordnance Survey maps, 200,000 photos and the involvement of all 30,000 schools in Britain, or about 1 million children.

The two LaserDiscs on which the data was to be stored held about 4GB and included all the software needed to browse the discs.

As well as a television series fronted by well-known TV historian Michael Wood and the involvement of the Open University, it was expected that 50 people would be required to produce the discs, at a forecast cost of £2 million, with the expense being in part justified as the project was seen as an ideal follow-up to the BBC's earlier Computer Literacy Project[45].

Slapton Ley, Devon, in 1989The project was loosely split in to two parts, with a "curated" disc as well as a community disc, featuring contributions from the public.

There were also some spin-offs, such as the Ecodisc, which provided an ecology simulation of the Slapton Ley nature reserve in Devon and which with the addition of the "Domesday Display floppy" could be used to extract data from the Domesday disc and turn it in to a slide show.

There was a catch though for anyone interested: in May 1987 the cost of a complete Domesday system - discs and LaserVision player and everything - increased by £500 to £5,160, or £18,900 in 2026.

Nearly twenty years after the project concluded, when a university team wanted to recover the data, the choice of medium - which was seen as "the technology of the future" - was revealed to be very much not the technology of the future as of the thousand Philips LaserVision players ever sold there were hardly any still working that could read the ancient digital format.

This was especially ironic given where the software to read the data was stored: on the disk itself.

The data was eventually recovered after a lot of work, but it did highlight the potential shortcomings of long-term electronic storage[46], despite the best efforts of the Domesday team which had also lodged its data with the National Archives, only for it to disappear[47].

In other video-disc news, Acorn had also spun off a new company - Acorn Video - to develop interactive computer video, using a BBC Micro and a Pioneer Laservision player.

Called the Acorn Interactive System and run out of Acorn International's HQ in Maidenhead, it was available for £3,500 (around £14,700 in 2026). Chris Curry said of the venture that:

"we have a good start in the field, but the Japanese are snapping at our heals"[48].

There was already competition in this area, with cheaper systems utilising standard VHS video players (but still including a BBC Micro) also being tried out, such as the £1,250 (£5,280) system at Barn Hall School in Essex[49].

And only a year later, the first user-writable optical disk drives were starting to appear, although the WORM - Write Once, Read Many - units weren't exactly cheap, with a drive capable of writing 500MB disks being launched at the beginning of 1986 for around £5,000, which is about £18,900 in 2026.

The BBC Model C lives, sort of

Meanwhile, Acorn was also having to thrash out the details of the rumoured BBC C, to which it was still contractually committed to build.

However, although design contractors had been approached, the undisclosed specification remained unaccepted by the BBC's Microcomputer project team[50].

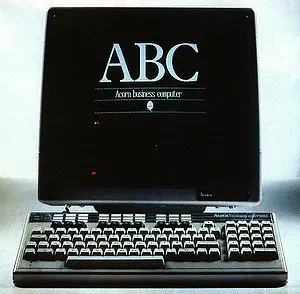

The BBC C never really appeared as it was quietly sidelined in favour of Acorn's Business Computer range, although that didn't stop Practical Computing calling the ABC the BBC Model C anyway in its November 1984 issue.

The confusion was understandable, as the ABC was actually based on the BBC B motherboard, although this was now housed in a green-screen monitor case.

Acorn's ABC: The Acorn Business Computer, from Practical Computing, November 1984The entry-level ABC Terminal came with nothing extra other than Econet built in, plus a University of Sussex VT-100 terminal emulation program. It was thought it was aimed at schools and colleges already running Econet networks.

The model perhaps closest to being a Model C was called the ABC Personal Assistant. This shipped with a disk controller, 640K floppy disk drive, Econet, the green screen, and copies of View and Viewsheet in ROM, putting it in the word processor market.

The remaining models came with some sort of second processor built in, essentially replacing the Torch Graduate or ZEP Z80 processor unit by using the on-board 6502 processor just as input/output to another system.

The rest of the range included the ABC-200 with National Semiconductor's 32016 chip, which Acorn claimed made the machine as powerful as a "DEC Vax on a desktop", through the ABC-210 with a bit more memory and the ability to run Xenix, right up to the ABC-310, which had an Intel 80286, floppy disks, a 10MB hard disk and a colour monitor.

Practical Computing had several questions, the first being whether Acorn had finally got around to re-engineering the BBC B motherboard in such a way as to reduce costs and increase reliability.

There were also questions about compatibility with the IBM world and how the ABC actually made use of its 80286 processor, in particular as it was running Digital Research's Concurrent DOS and not MS-DOS.

Thirdly it pointed out that there was a big jump between the Z80 variant and the 80286, with a gap which used to be filled by the Graduate, the almost PC-in-a-box which used Intel's older 8088 CPU.

The remaining questions it had about the new range were more pragmatic:

"Fourth, will Acorn take advice and restyle the ABC range in two-tone grey and cream? Surely the machines do not have to look horrible? Fifth and sixth, when will they be available and what will they cost? Prices will range from about £600 to £5,000, depending on the state of the market when the machines finally appear. Acorn is talking of launching the range in January 1985, but availability is anyone’s guesss[51]".

The equivalent prices in 2026 would be from £2,530 to £21,100.

Date created: 12 October 2019

Last updated: 01 February 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.