Sinclair Advert - March 1985

From Your Computer

Turn your Spectrum into a Spectrum+ for just £20

1985 was the beginning of the end for Sinclair, at least as far as Uncle Clive was concerned.

The company's "next generation" QL, launched in January 1984 but not actually available until April of that year, had managed to shift only 50,000 units in its first year since launch[1].

In December's Your Computer, the QL was referred to as having been "virtually given up for dead after an apparently never-ending series of teething troubles", although the magazine did concede that "the price cut and the new improved versions of the bundled software might just rescue this one from the realms of academic curiosity piece".

It concluded with the faintly-damning "Slow and cumbersome BASIC, awful keyboard and of course Microdrives"[2].

Nigel Searle, long-time Sinclair trustee, © Popular Computing Weekly, 15th September 1983Production and deliveries had been cut back, with that of the QL suspended for a couple of months in March as warehouses were full of the things.

By May of 1985 the company was admitting that its unsold stock had increased almost three-fold to £34 million since September of the previous year, although it was also keen to report that its overdraft was down to only £5 million[3].

Sinclair had also postponed its US launch of the QL and it had lost one of its distributors, Lightning, which had moved on to the Amstrad - ironically the company that would buy Sinclair out the following year.

Overstocking during the Christmas 1984 run-up was blamed for the "short-term rescheduling of supply and production" - Sinclair was keen to make it clear that it was not going to be lumbered with "an Electron-style Spectrum mountain"[4], a reference to Acorn's warehouses full of Electrons which helped to nearly bankrupt Acorn.

The QL was due to eventually launch in the US by mail order in early May, by which time Sinclair was claiming sales of 60,000 units.

The Spectrum Plus had also given Sinclair problems during the Christmas 1984 period as reliability problems and the sheer number of faulty machines had led to a major shortage of the machine. John Flatman, of Boots' computer-buying department suggested that:

"the shortage of Spectrum+ machines is having a devastating effect on the Christmas market. People are waiting until the mahine finally arrives rather than buying an ordinary Spectrum, and it seems there are severe quality problems with the machine".

WH Smith also claimed that it was not getting the machines it needed, as a spokeswoman reported that it was having problems with the keyboards in that many of the keys seemed to be loose. The problem was said to be so bad that the machines were being individually tested "as they come out of the boxes".

Meanwhile, Sinclair was avoiding the issue as it was "not aware that the situation [was] at all difficult".

A spokesman for the company said simply that "My impression is that things are a lot more positive this year than they were twelve months ago"[5].

Marathon man

Clive Sinclair in the Cambridge Festival half marathon, © Popular Computing Weekly, 28th July 1983In the press, Sinclair was also getting heat for a television advert which showed him athletically jumping dozens of feet in the air in a tracksuit.

The ads claimed that the QL would be the machine that every dealer would buy given up to £2,500 to spend, but Your Computer magazine couldn't find a single dealer that agreed[6].

Sinclair was famous for his running and the company even sponsored the Sinclair Cambridge Festival Half Marathon, which Clive and several other members of staff entered, including managing director Nigel Searle.

However in the 1983 race, Clive - who came home in 949th place - lost out to Sinclair's finance director Bill Matthews by around 17 minutes, even though Uncle Clive had bested his run from the previous year by four minutes[7].

Perhaps all the press vitriol was a bit unfair, as in the editorial in July 1985's Your Computer, it was pointed out that Sinclair had turned the UK in to the most sophisticated market in the world, leading to Britain having more computers per capita than anywhere else on the planet[8].

It seems that at least Madame Tussauds, the famous waxworks museum in London, took the same view as it had prepared a model of Sir Clive for display sometime during 1985.

Sinclair's wax model was being created at the same time as Joan Collins, the actress credited with reviving the fortunes of struggled US soap "Dynasty"[9], with Personal Computer News hoping that they didn't "mix the pair of them up"[10].

The model of Sir Clive, which had been completed at the end of 1984, was actually intended to be part of a tableau also featuring TV presenter Selina Scott, with Clive holding one of his pocket TVs and Scott "looking over his shoulder, looking at the TV screen, on which there will be a picture of herself", according to a spokeswoman for Madame Tussauds[11].

Elsewhere, in the March of 1985, Sinclair revealed a few more details of future projects including a "silicon disk drive" - a solid-state portable RAM disk made out of a single large wafer of silicon, with a storage capacity of 512K.

Initially intended for the QL, it also had back-up batteries which could be changed whilst the unit was plugged in.

Sinclair wouldn't give any details on the technology used, but it was expected to be working by the second prototype stage, which implied that it would have been fairly simple[12].

There was also talk of the fabled Spectrum Portable - also known as the Pandora - where it was thought that the silicon drive would feature as storage device.

The £300 silicon disk was expected to be in the shops sometime towards the end of 1985, according to director of engineering Hugo Davenport[13].

The Sinclair Pocket TV, a.k.a. Microvision, from Popular Computing Weekly, June 1985In the early summer of 1985, Sinclair announced that it was changing its guarantee period on Spectrums.

Previously, Spectrum owners could exchange faulty models over the counter for up to 12 months, however Sir Clive blamed this generosity as the reason why Sinclair was suffering from a widely-publicised high returns rate as people "traded in an eleven-month-old model for a new one".

The new return period was reduced to 30 days, in line with the rest of the micro industry[14].

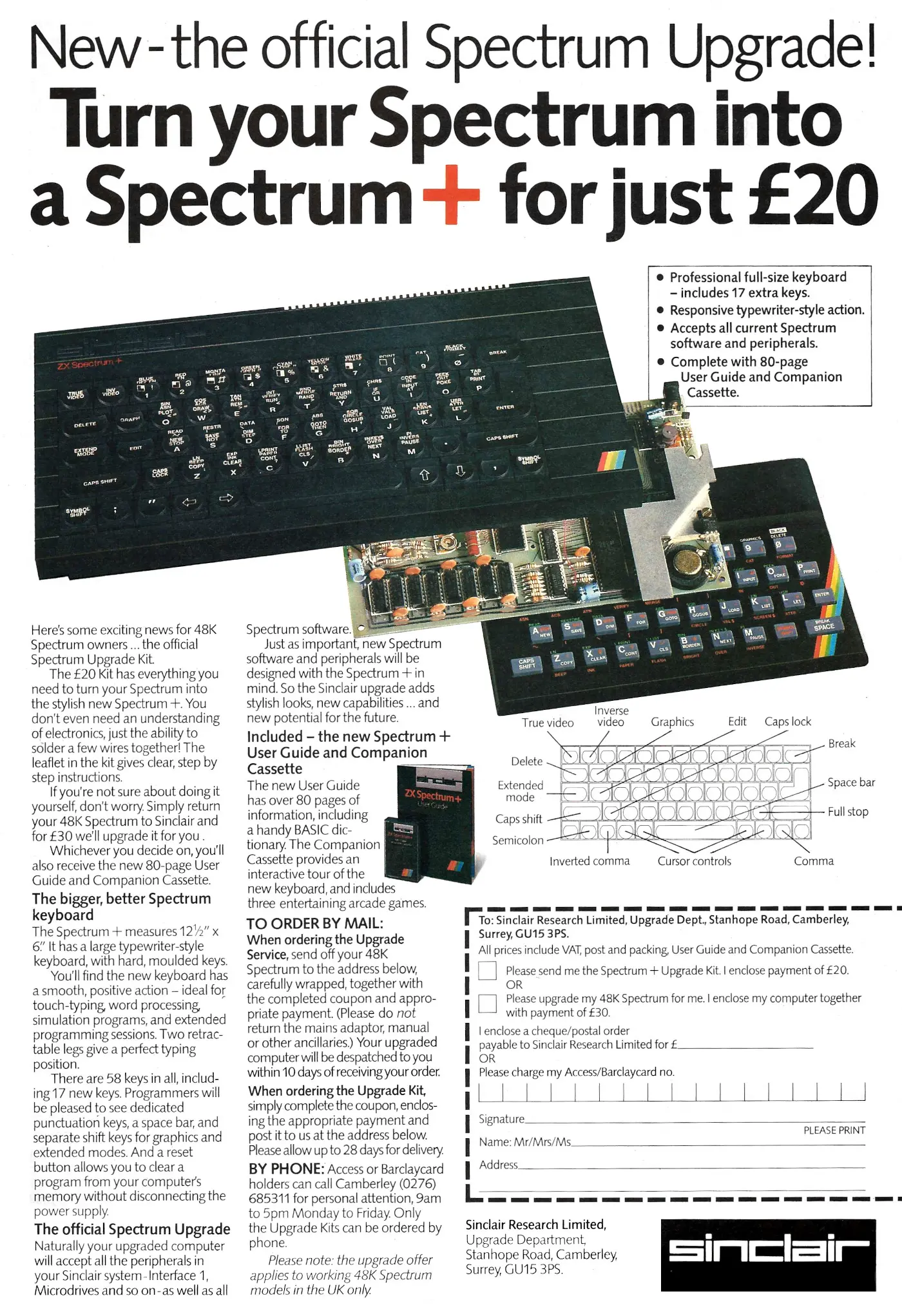

To keep the money coming in, the ageing Spectrum was refreshed.

This version - the Spectrum+ - appeared to only offer an improved QL-derived keyboard (so it was no longer made of "dead flesh" and had a few extra keys on it) and a reset button as the only really new features over the original 1982 machine.

An upgrade kit for existing Spectrum owners was available for £20 (£83 in 2026) which the owner could install themselves, or you could send your Speccy back to Sinclair and they would do the job for £30 (£120).

It doesn't seem as though this was enough to encourage the hordes to buy Spectrums again, as in July 1985's Your Computer it was reported that Sinclair was "trying to wake up Spectrum sales" with a £200 (£830) bundle sold through Dixons which included the computer, a ZX Printer, a bunch of software and one of Sinclair's other noble follies, the pocket flat-screen television known as "Microvision"[15].

Although this wouldn't work with the computer, as the TV didn't have an external aerial socket and you wouldn't be able read the text on it anyway, Sinclair was obviously thinking that small portable TVs (worth £100, or £410 in 2026) were the thing to buy in summer, when micro sales were traditionally low[16].

Even though the bundle included the printer, which hadn't been produced for about a year and so was clearly an attempt to clear out stocks, it wasn't the case with the micro-TV.

This was seen by some as potentially Sinclair's most successful product, as the company had recently won major orders from American Express and mega-retail group Sears in the US[17].

Despite the optimism, June 1985 marked the moment that Sinclair ran into financial trouble for the first time ever since its founding in 1979, six years before.

It was looking for between £10 million and £15 million, from "industrial or other sources", to rescue it from its debts, largely caused by the failure of the QL and its massive pile of machines in the warehouse.

It was also - like other manufacturers - struggling with a very flat market, all of which was made worse by the fact that it had no new machines on the horizon to shake things up. As Popular Computing Weekly's editor David Kelly suggested:

"what Sinclair needs now is a machine aimed directly at the existing market. Additions to the QL range would be all very well, had the QL created a market. It hasn't. The portable Pandora, or at least a straight 128K Spectrum would seem the best bet".

Meanwhile, Sinclair's manufacturers, Timex and Thorn-EMI, had already extended their credit for an additional two months, and the company was also reported to be thinking about selling off electric scooter offshoot Sinclair Vehicles.

Even though Sinclair claimed that its warehouse stocks were down slightly from their £34 million high, as it was managing to shift units, it was still forecasting a 20% drop in sales for the year.

Companies that had been approached for a cash injection included Thorn EMI, STC, GEC (temporary rescuers of Dragon Data) and Dutch company Phillips, however even when it came to a rescue the company was being picky, with a Sinclair spokesman stating that "Sir Clive's patriotism and support of British firms means he would prefer it to be a British company"[18].

The death of the C5

Clive Sinclair looking glum in front of a C5, © Your Computer, September 1985By the end of the year, Clive's other pet project of the day, the one-seat electric scooter C5, was toast.

Research on electric vehicles at Sinclair dated back to 1973 and the Radionics days, but began in earnest with the creation of Sinclair Research in 1981.

In early 1983 a Sinclair share placement raised £12.9 million which was used to fund the electric car development as a spin-off venture, under the guidance of Barrie Wills[19], formerly of DeLorean Motor Company[20].

This was initially reported to have been based in Exeter, although the location seemed to change every week, as Popular Computing Weekly had reported Winchester the week before[21].

However by February 1984, Sinclair Vehicles had been formally set up as a separate company, based at the Venture Centre at the University of Warwick's Science Park[22].

Car company Lotus was bought in to oversee the C5's production, whilst actual manufacturing was done by domestic appliance maker Hoover at its Welsh factory. This helped create the myth that the C5 used a washing-machine motor.

The company even had an option to buy the former DeLorean car plant in Dunmurry, Northern Ireland - home not only to Doc Brown's time-travelling car but also to "one of the most advanced plastic moulding systems in Europe" - before it abandoned the idea in May[23].

The C5 project was a disaster though, with only 12,000 C5's thought to have been built. By the end of the year, Sinclair Vehicles, or TPD as it was then known as, collapsed with debts of £1 million.

It was thought that Sir Clive had lost £8 million - mostly his own money - on the C5 and his electric vehicle projects[24].

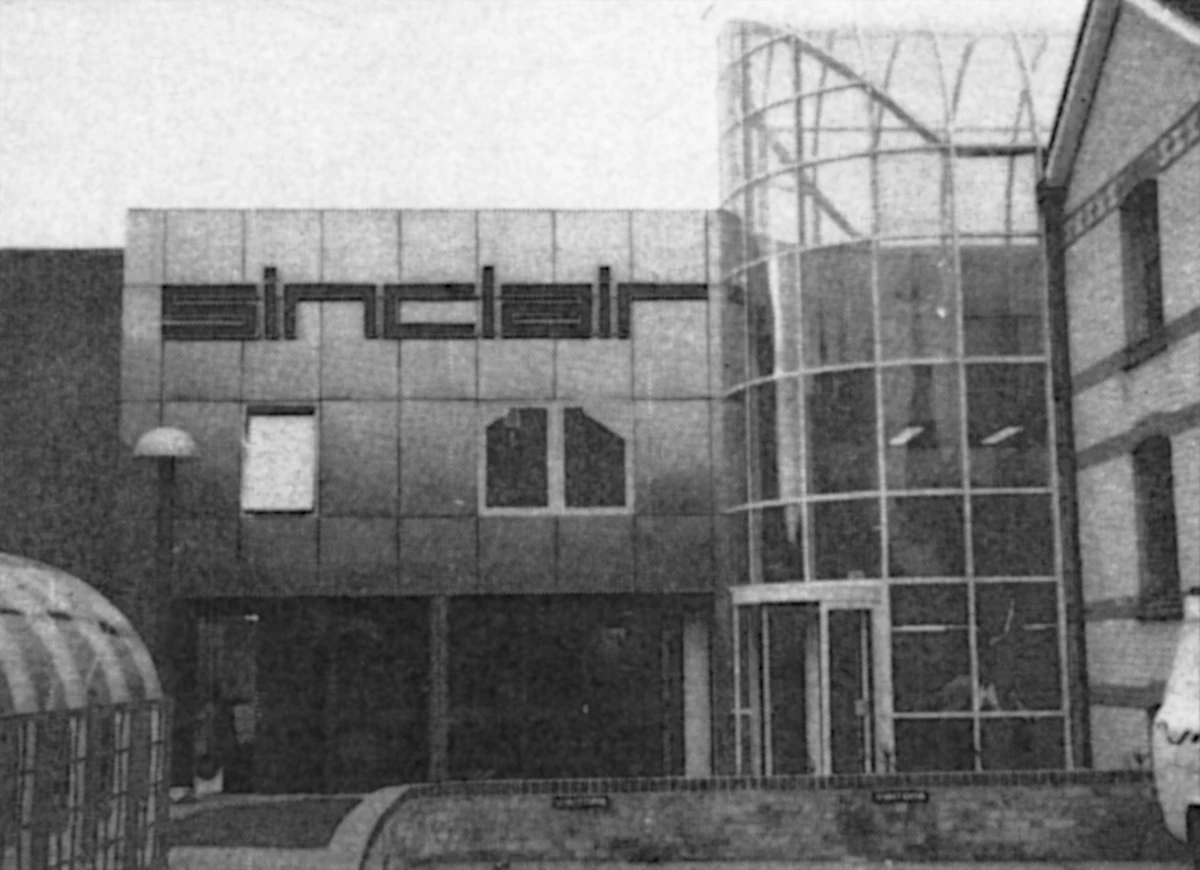

Sinclair's Willis Road head office, purchased in 1983 but sold off again in 1985. From Your Computer, April 1983

Sinclair downsizes and Jim Westwood leaves the board

To add insult to injury, as part of a survival streamlining of its operations in November 1985, Sinclair was forced to move from its prestigious offices on Willis Road in Cambridge over to its Milton Hall site, where its Metalab research offshoot was based.

The Willis Road office, which had been purchased in the early spring of 1983, was then sold off to Cambridgeshire County Council in December.

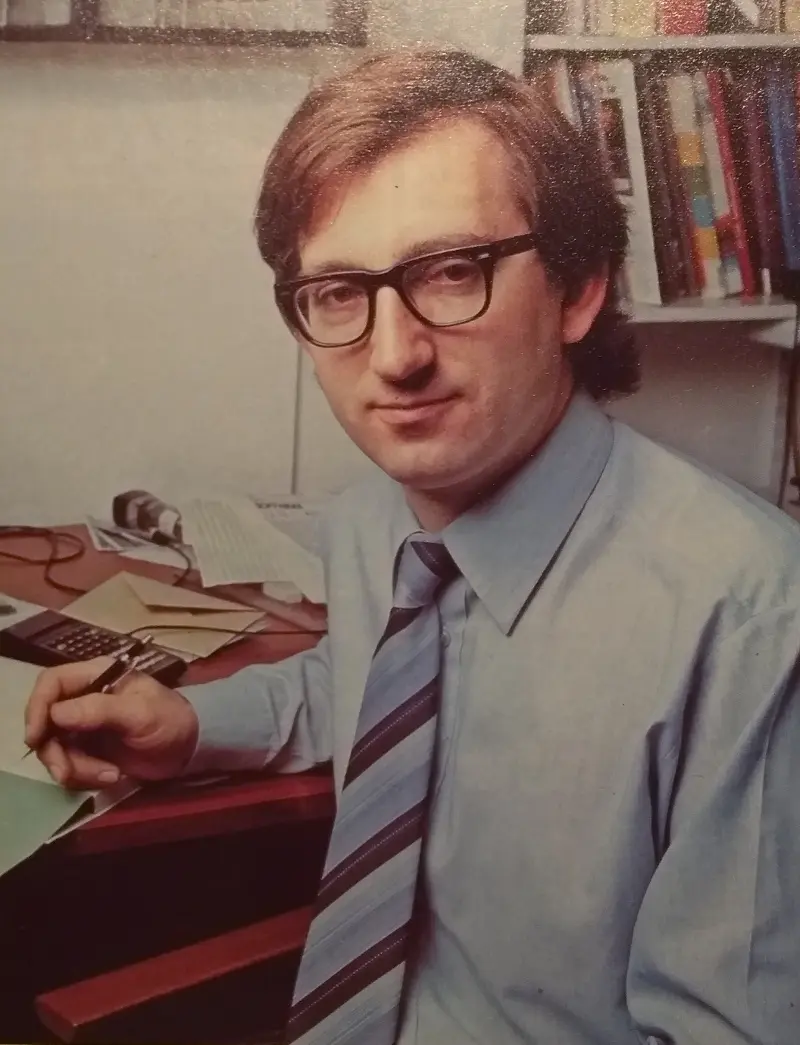

At the same time it laid off 10% of its 120 employees, having already lost Robb Wilmot, formerly of TI and currently chairman of ICL, and Nigel Searle - a long-term Sinclair trustee who had been sent out to head up Sinclair's US operation - as board members, earlier in March[25].

Also losing a seat was Jim Westwood[26], Sinclair's chief engineer and designer for Sinclair products for over 20 years, from hi-fi at Radionics to the ZX80 and beyond, as the board shrank from thirteen to only five members.

Jim Westwood - chief engineer, © Sinclair User 1983Westwood's career in engineering had arguably started at the age of 12, when he devised some apparatus which allowed him to do soldering from the comfort of his own bed. He said of growing up that:

"Engineering of a kind was always my hobby, even when I was very young. Wherever I went you could be sure of finding a trail of broken torches in my wake. I had to take everything to pieces and gradually I was able to put it back together again".

Westwood joined Radionics in the early 1960s when it was just Clive plus a secretary, and went on to have a hand in Sinclair's pocket calculators, micros and the flat-screen TV, all the while relying on trial-and-error and a natural aptitude for engineering to get by in the early days.

By the early 80s - and at the age of only 34 - he was Sinclair's senior engineer and reckoned that:

"it must be unusual to find someone like me in a fairly senior position without any formal training, but when you are always working unconventionally as we are at Sinclair Research, I don't think training matters very much. Aptitude is more important".

In an interview with Sinclair User, Westwood offered some interesting insights into the way Sinclair worked, in particular given how it was often producing firsts in the market and so had nothing much to go on, saying:

"The most difficult part is deciding what we want to achieve in the first place, [but] all of us here have electronics in our bones and so when we first discuss an idea we know roughly its chances. The real worry is always whether [the idea] will catch on. You might feel sure there is a certain demand in the market but you are never sure just how well it will sell".

Westwood - who admitted that he would flinch at the sound of some of Clive's ideas - dismissed his own contribution as simply "fiddling with the components and trying to get the thing working". However he was clearly proud of his Sinclair team, suggesting that:

"We are always surprised at how long it takes the rest of the world to catch up with us. After working with Clive for years, you learn that it is worth trying to do things other than the straightforward way. It has amazing benefits. All our products show imagination and inventiveness; they make other people envy us and want to work for us"[27].

The birth of Metalab

Metalab, meanwhile, had been set up in happier times with £2 million of Sinclair money in the summer of 1983.

Headed up by Richard Cutting, former managing director of Cambridge Consultants, where Sinclair had been on the board in the 1970s, Metalab was "a kind of think-tank" which, as Sinclair himself said, "will not only complement research work underway in the existing computer and television divisions [but] will also open up totally new fields ranging from battery technology to robotics[28].

It proved so attractive that Sinclair received over 1,000 applications for the twelve "top-flight" research posts on offer, with "nearly all of the 1,000 applications [being] of an extremely high quality"[29].

Metalab was seen as a rare UK equivalent of the start-up/incubator ethos that was prevalent in Silicon Valley and elsewhere in the US and was a deliberate attempt to "gather the brightest young minds in the country under one roof, pay them large salaries, give them unrivaled resources and take the resulting products through to the market place".

This compared to the usual UK set-up where academia and industry were kept apart, researchers were paid poorly and any end result was given to someone else - quite often in another country entirely - to market. Popular Computing Weekly in its 21st July issue concluded in an editorial that:

"Whether or not [it] is a success remains to be seen. Certainly, Sir Clive is the man with the Midas touch at the moment. The idea deserves to succeed, if only because it is an investment in the future"[30].

Also in December of 1985, first glimpses of a proper Spectrum upgrade were sighted in the UK.

Un-denied rumours of a 128K Speccy with the same audio chip as used in Amstrad's machines and similar to those in the MSX range - the AY-3-8910 - had been around since May, and by August first hints of a possible Spanish connection were unleashed courtesy of Spain's Micro-hobby Week magazine.

Sinclair had done a cash-raising deal in the summer with Dixons, which took on the huge stockpiles of unsold QLs and Spectrum Pluses (it was thought there was about £30 million worth of stock in warehouses after Christmas of 1984, which was certainly ironic given the company's "no Electron-style mountain" comments) in return for an agreement that Sinclair would not launch any new machines in the UK until 1986.

Sinclair however still needed to develop its Pandora and QL II but the rumoured Spectrum 128 was still not officially part of that plan, with Sinclair's Sales and Marketing director Charles Cotton stating that "[it] doesn't fit into the UK picture just now".

So there was some surprise when the Spectrum 128 did get manufactured in Spain by Investronica[31], with Cotton continuing "the impetus to introduce a Spectrum 128K in Spain comes from the particular market forces operating there".

There had also been a suggestion that Sinclair's own creditors would not have stumped up the cash to allow the company to "tool up to produce a new micro" and also that even if they had, according to a source at one of Sinclair's major distributors, there was "no way that [Sinclair] could bring through enough production to service the demand had they launched a 128K model this Christmas"[32].

Personal Computer World continued by suggesting that if Spain should fill some of its trawlers with the 128K machine and launch a new Armada for Christmas, it would find that it 'fits into the UK picture' like a jigsaw piece[33].

Even though Sinclair was remaining silent on the matter, several UK software houses were pre-empting it anyway, having had Spanish ROM versions of the machine for several months in order to develop software for that market.

However, by the January of 1986 it was thought that English ROM versions were being shipped, and companies like Tasman Software were busy porting their Amstrad CPC 6128 version of Tasword to the new machine, although on the down side it was planning on releasing it in Microdrive format only.

Many other companies, like Melbourne House, DK'Tronics and Firebird, were also working on 128 ports.

Meanwhile, Boots was also expecting the imminent arrival of the 128, with the company's John Greengrass stating that "We have spoken to Sinclair and expect to be taking it"[34].

The Spectrum 128 Finally Appears

The Spectrum 128 had been launched at the Barcelona Computer Fair on Monday September 23rd 1985 and not unexpectedly shipped with a Spanish keyboard, firmware and manuals.

Development costs for the machine had been entirely borne by Investronica, Sinclair's Spanish distributor, but it was still thought that the UK version - expected to be available from the beginning of 1986 - would be built in the UK[35].

As usual, Sinclair was being cagey, saying:

"we are not giving out any details of the machine - it is for the Spanish market so we are not publicising it. We do not have a release date for the machine in the UK".

Despite the denials, by the end of the year it was thought that the 128 would launch in the UK at the end of January 1986 - either the 30th or the 31st.

This was preceeded by the dropping of the price of the Spectrum+ to under £100 for the first time, at least at WH Smith which was selling the un-bundled machine for £99.95.

Smiths explained what it said was a good move by suggesting that "People might well want to buy the micro on its own", which was a reference to the prevalent bundled offer for the Plus which included software, a joystick and Sinclair Interface. The Smith's spokesman continued:

"It's a unilateral move and does not emanate from Sinclair, and I don't know how long this offer will last. We'll see how things go".

The company was totally denying that its price cut had anything whatsoever to do with the impending launch of the Spectrum 128[36].

There was much mystery and intrigue afoot when a consignment of 128s appeared in the UK in the first half of November.

Thought to be the first bulk delivery of the machine, the 3,000 kits had come from Samsung in Seoul, Korea, via Tokyo and had ended up at MCK Freight in Cottenham near Cambridge.

Sinclair was being particularly secretive, with a spokesman stating "I have no knowledge of any such machines", although he went on to concede that "A British version of the Spectrum 128 may be introduced in Spring 1986".

It was also thought possible that the mystery machines might simply be on their way to somewhere outside the UK, perhaps to Spain in order to top up supplies prior to the expected Christmas rush, rather than as part of a pre-launch UK stockpile[37].

It's notable that at this time the press still seemed largely unaware of Sinclair's impending doom, and was fully expecting to see the Pandora portable and a 3½"-floppy-based QL during the following year, as well as the 128K Spectrum.

These other machines never appeared, as Sinclair was bought by Amstrad in April 1986 for £5 million in loose change, plus debt, and the projects were promptly cancelled.

The Spectrum 128 did manage to get launched in the third week of February and completed a full house of very similar models from all the major manufacturers, with Amstrad's 6128, a BBC 128K machine and Commodore's 128 all marking the first time that the big four had machines with the same amount of memory.

In some ways the move to 128K was all a bit pointless, as BASIC programmers couldn't really make use of the extra memory, but some software houses used the extra to provide a few extra levels in adventure games, additional graphics, larger word-processing documents or, in the case of the Commodore 128, richer music[38].

Despite the minor bump in memory, the 128K Spectrum, which differed from the Spanish version in its lack of built-in numeric keypad[39], was touted as compatible with the existing 16 and 48K models.

However mail-order software dealer Speedysoft tested 71 popular titles and revealed that 26 of them were in fact incompatible[40].

The price of the machine was also not considered especially impressive, as its £180 pitched it close to Amstrad's CPC 464, which came bundled with a monitor and a tape recorder.

Amstrad was Sinclair's main threat (in more ways than one given what would happen a couple of months later), and Popular Computing Weekly suspected that the incremental improvements of the 128 only gave Sinclair - which it said was once a visionary maverick which could do no wrong but which was now a near bankrupt whose idiosyncrasy led it up a whole series of near-fatal cul-de-sacs - at most six months' grace before some new mass-market machine came along and stole its market[41].

The Maxwell Takeover That Nearly Was

Back in the summer, whilst "new Spectrum" rumours were swirling around, the unexpected news that gazillionaire media-baron Robert Maxwell's Pergamon Press subsidiary Hollis - a publicly-quoted supplier of office equipment and furniture[42] - was planning a £12 million shock rescue/take-over of Sinclair broke, revealing that preparations for the purchase of 75% of Sinclair for a nominal sum with £12 million being raised via a three-for-one rights issue at £1 per share were already well underway with expectations that everything would be complete by the middle of September 1985.

This valued Sinclair at only £16 million, a fraction of the £130 million it was worth at the beginning of 1984 whilst Clive was set to see his holding reduced from 80% to 10 or 20%, although he who would remain as life president and research consultant[43].

Uncle Clive was reported to have said about the prospective rescue "I am absolutely delighted. Robert Maxwell is a really great bloke"[44] whilst Maxwell replied:

"I was glad to have been able to help in the survival of Sinclair Research, one of Britain's great national assets. I look forward to working with Sir Clive - a man of brilliant inventive genius".

Negotiations over the deal had taken place for nine hours at Maxwell's Pergamon Press headquarters in Oxford[45].

Sinclair had also reported as offering an explanation as to why he seemed to exhibit a knack for building up fortunes and then losing them by saying "I am an inventor - I am awful at managing established businesses"[46].

The 2006 Science Park Fun Run in front of Cambridge Consultants' offices - a.k.a. the Milton Hilton - on Cambridge Science ParkThe pair had actually been aquainted for 15 years since the time they were both involved with Cambridge Consultants.

Maxwell had wanted to invest in CCL as it was expanding, but the consultants didn't want his money and went with Clive Sinclair instead[47].

Sir Clive was comfortable with the rescue deal as he'd said he didn't want to run the company himself and had never pretended he wanted to, whilst both, despite being at opposite ends of the political spectrum were hard-line patriots and wanted to do the best for UK PLC, with Sinclair expressing an intent to supply the UK with the necessary silicon technology for the next twenty years, a goal that Maxwell was sympathic towards[48].

The deal itself had been instigated by the Bank of England, on account of Sinclair's desperate financial troubles, at a time when Timex of Dundee, the manufacturer of Sinclair's computers, had laid off 400 Spectrum+ assembly workers as there were no more orders[49] and the company had £34 million-worth of unsold stock in the warehouse.

Why Maxwell anyway?

On the face of it, there wasn't an obvious match apart from Sinclair and Maxwell's long-term aquaintance, however Maxwell did have several interests in technology and computers.

One such interest was his Mirrorsoft offshoot, inherited when Maxwell bought Mirror Group Newspapers and which had been doing good business for a couple of years.

Mirrorsoft had established a reputation for a diverse range of software titles - from early years to weight loss and astronomy[50] - since it had launched back in November 1983 with just three titles to its name.

At the time, The Mirror's Jim MacKonochie said of the launch of its software offshoot that:

"We believe that home computers will become part of the furniture of our everyday lives, just like hi-fi"[51].

Maxwell would also go on to buy the on-line Official Airline Guide in 1988[52] and by the end of that year had become a significant force in the world of connected data, having started out with Pergamon Infoline, which was considered as one of the pioneers of the online information industry.

Whilst Maxwell failed to buy one of the largest publicly-accessible databases - Dialog - from Lockheed during 1988, it did manage to buy New York-based BRS Information Technologies via Maxwell's recent $2.6 billion aquisition of the Macmillan publishing group.

The deal would merge BRS, which specialised in medical databases for doctors, with Pergamon Orbit Infoline, and was expected to double Maxwell's online presence.

Pergamon was also demonstrating that it had an eye on what was seen as an emerging threat from CD-ROMs - which offered quick access to massive amounts of data with no time-based access charges and which observers believed might destroy the online market - as it was already a pioneer in the CD-ROM business via its Pergamon Compact Solution business.

Even the British Library was moving its 360-volume cataloge onto CD-ROM, although at £8,000 its three-disc alternative to bound paper was not exactly cheap[53].

The Maxwell deal would leave Sinclair with the C5 car project as well as his 5th generation chip plans centred around the Metalab research centre, plus a rumoured £99 mobile phone and the Pandora portable, with Sinclair himself remaining as a retained inventor and R&D director.

Meanwhile, a new chief executive for Sinclair - Bill Jeffrey, formerly head of radar and navigation sales at Mars Electronics and currently managing director of Sinclair TV and Communications - had even been appointed.

Ironically, the fabled flat-screen TV was finally in the shops just as Polaroid announced that it was ceasing production of the long-life Lithium batteries that the thing needed[54].

Hoover sucks up to the lawyers

However as the negotiations progressed, exactly which parts of the Sinclair empire would or would not be included or left out of the deal seemed to change on a weekly basis, with the only certainty being that the company needed to close a deal quickly, with Sinclair being in trouble on several fronts.

One of these was over at Sinclair Vehicles where Hoover, manufacturer of the C5, had taken out a writ against Sir Clive for a non-payment of £1.5 million in un-paid debts, incurred between November 1984 and June '85.

The company, as at the end of July 1985, had yet to actually serve the writ and appeared to be using it as a bargaining tool.

A spokesman for Sinclair shrugged off the threatened legal action by suggesting that "Until they [serve the writ], as far as Sinclair is concerned, it effectively does not exist".

All this was going on whilst Sir Clive was on holiday in the United States[55].

Rumours were also doing the rounds in the press during July that the rescue deal was in trouble, but a Sinclair spokesman refuted this by saying "The takeover should be completed by September". The reason for the delay seemed to be that:

"When one of the companies involved in any such deal is listed on the stock exchange, as Hollis is, there are strict rules of practice that must be followed, and these take time"[56].

Almost inevitably, the Maxwell deal fell through in August, although following the £10 million order for the Spectrum Plus, flat-screen TV and the QL from Dixons, Sinclair was quick to suggest that he now didn't need the money anyway.

The deal had collapsed when Maxwell's accountants Coopers and Lybrand had reported back to the merchant bank Hill Samuel on Sinclair's prospects, which were clearly not good.

Maxwell concluded that the plan for Hollis to buy Sinclair "just did not gel", whilst the merchant bankers could not recommend the deal to Hollis's shareholders.

Popular Computing Weekly prophesied as much when editor David Kelly suggested in his 20th June editorial that "Sir Clive is a loner and his association with Robert Maxwell is unlikely to be prolonged"[57].

Sinclair for its part clearly thought that its sales of the QL in the US would help to carry it through the bad times. Nigel Searle, who was heading up the US operation, stated that:

"We have been shipping the QL to customers since June. The demand has been high, although we have tailored our marketing efforts to match the extent of production".

This optimism was despite the fact that at the time only 25,000 people in the States had even "requested info on the QL", let alone actually bought one of them[58].

Searle's reference to the extent of production was telling as it was thought that the company's cash problems were at least in part the cause of its inability buy components to be able to meet demand, which it desperately needed more than ever in order to build computers for the up-coming Christmas period.

Longer term, the company seriously needed the rumoured 128K Spectrum and a new 512K micro, especially as Amstrad had just rushed out its own 128K machine at a highly-competitive price[59].

Sir Clive was claiming, as well as the Dixons deal, that he was re-starting talks with three other companies which had expressed an interest before Maxwell came along. A Sinclair spokesman concluded:

"We're not saying now that everything's 'roses around the door', but there is light at the end of the tunnel".

Despite the major setback of the failure of the Maxwell deal and the complete failure of the C5, creditors nevertheless agreed "not to pull the rug on Sir Clive" and allowed Sinclair to continue trading in order to see through the Christmas sales period[60] and hopefully survive long enough so that it could launch the fabled Pandora portable, also known as the ZX84[61]), Spectrum 128 and QL II in the following year.

The survival deal was put together end of August and involved the five main creditors - Barclays, Citibank, Thorn EMI, Timex and AB Electronics - which were owed about £15 million between them.

The same five creditors had already met at the beginning of June in order to agree "a level of support" for Sinclair after Timex, which was already working a three-day-week on Sinclair products until the factory's summer holidays, had sold off its stock of Spectrums to Cheshire-based Zeta Services in order to recoup some of the money owed to it[62].

Zeta seemed quite happy with this deal as the company's Jim McCormack said "We took 65,000 Spectrums from Timex and we've already sold out! I have never known such unprecendented demand for a product"[63].

Meanwhile, the management team was re-arranged by CEO Bill Jeffrey and there were changes made to the board, but Sinclair kept his 85% stake in the company.

However its future was now contingent upon maintaining its 44% market share[64].

Sinclair's Other Research

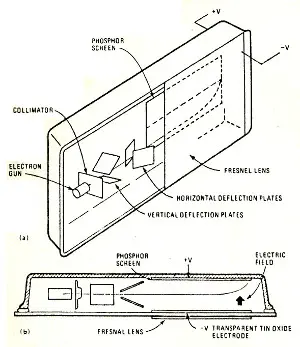

Sinclair Flat CRT Schematic, © Electronics and Computing, April 1983The Pandora was something of a moveable feast during its development and had initially expected to be based upon Spectrum technology, but by the time it had got to the point when it was "definitely" going to be released, it had moved on to the QL's 68008 chip.

For a while it also attempted to use Sinclair's flat-screen TV technology, which used a fresnel lens and some contorted CRT technology to squash what was essentially a small telly sideways in to a much larger display, before abandoning the whole idea after years of development as the company could never get it past about 66 characters per line.

By the end of 1985, Sinclair's Alison Maguire - former software evaluator and now marketing manager - was saying:

"Our portable computer development program is going ahead, however our conception of how the machine fits in with the rest of our range can change".

It was originally hoped that the finished machine would launch at the very beginning of 1986, but a Sinclair spokesman put the dampers on that hope when he said:

"I don't know exactly when we'll introduce it. It'll still be 1986, but not the beginning"[65].

It wasn't to be and only the Spectrum 128 happened before Sinclair folded and was bought out by brash new upstart Amstrad in 1986.

A month or so before all this, Sinclair's research outpost Metalab, based at Milton Hall in Cambridge, had been investigating applications of optical memory systems, including Phillip's new CD-ROM player and the Drexon LaserCard.

The credit-card-sized LaserCard, manufactured by Silicon Valley company Drexler Technology, could store up to 4MB on a strip of photo-optical recording material in either read-only or write-once mode.

Coincidentally, the only current licensee of Drexler's technology in the UK at the time was BPCC Graphics, part of Robert Maxwell's British Printing and Communications Corporation.

This was related to Hollis - the part of the Maxwell empire that had been negotiating to take a controlling stake in Sinclair before that deal collapsed.

Whilst BPCC Graphics' Peter Howgate said "Discussion [over the Drexon LaserCard] would take place with Sinclair - the QL would fall squarely in the area where you could apply this technology", Metalabs' chief Richard Cutting replied that "Sinclair is well-aware of the Drexler technology and we have been talking to that company".

Robb Wilmot of ICL and Sinclair, © Popular Computing Weekly March 1985It was also thought that Sinclair was evaluating a prototype of Philip's CD-ROM player, which the Dutch company would later claim to be the first to go into full-scale production, when it started full-scale production of the 600MB CM-100 model in June 1985.

The initial production was allocated to an un-named "major computer manufacturer", but it was thought it wouldn't be long before the device was available for other manufacturers like Sinclair[66].

However Cutting was quick to deflect interest in CD-ROMs, reiterating that Sinclair was still pursuing its own Wafer-Scale Integration solid-state memory project, saying "It was well publicised before the take-over that we were pursuing that line of research, and there is no reason why we should not continue to do so"[67].

The £50 million wafer project was continuing despite the fact that Robb Wilmot, the managing director of ICL, recent member of the Sinclair board, and mastermind of the project, had departed following a large cost-reducing re-structuring of Sinclair which saw the board reduced from 13 to 5 members.

A Sinclair spokesman explained "Robb Wilmot assisted in the development of a business plan for the wafer-scale integration plant but this was put on the back burner because of Sinclair's preoccupation with other things during the summer, and also because fundraising is based on confidence"[68].

The Dawn of the CD-ROM

There was clearly a lot of activity in the wider storage market, with several major Japanese electronics companies developing audio Compact Disc players as computer data-storage devices.

The attraction was simple: floppies could hold about 1MB, hard disks around 10MB, but a data CD-ROM could hold 600MB.

They were also said to be less prone to damage, more reliable and - at the time - could not easily be copied.

Sony UK's MSX product development manager Mike Margolis said:

"Sony has been researching into the use of compact disc for a long time. Virtually since CD first appeared we have been looking into the possibilities of digital data storage on it. We have made prototypes of CDs as storage systems, but anything finished is a very long way off".

The first prototype players were data-only and couldn't play music CDs, but the long-term aim was to produce a player that could do both[69]. A Popular Computing Weekly editorial predicted that:

"With CD software the micro becomes part of a racked system incorporating a hi-fi, video, television and radio. Just as you might play a disc of Springsteen, so you could slot in and play a computer game, several megabytes in size, looking more like an interactive film than Space Invaders".

The editorial went on to suggest, accurately as it happened, that:

"Soon there will be no need to know what goes on under the bonnet of your computer. There will be no need to learn BASIC or machine-code in order to drive it"[70].

There weren't only CD-ROMs and optical LaserCards, but also technology like "software cards".

Not a million miles away from plug-in ROMs popular since the late 1970s, "software cards" were credit-card-sized pieces of plastic with up to 128K storage on board, which had been developed in Japan by Astar International.

They were distributed in the UK by Electric Software of Cambridge, which was already shipping its own games for MSX machines in the format - adapters for MSX were already available, with Spectrum, QL, Commodore 64 and BBC Model B variants to follow.

The Sofcard, as it was known, was also being touted as an anti-piracy device, similar to a dongle, an application to which "'Beyond, Activision and US Gold' were very positive, as are distibutors like Lightning".

The battery-backed Sofcard had an estimated lifespan of two to three years, which apparently made it of interest to business software suppliers, which could factor in obsolescence into their products, thanks to Sofcard's built-in self-destruct[71].

Luckily for believers of the concept of owning stuff that you've paid for, rather than merely aquiring some temporary licence - and despite Astar's UK agent Peter Ryde suggesting that 20 million Sofcards could be sold in Europe by the end of 1986, with up to 80 million in five years - the self-immolating software delivery platform failed to take off, although closely-related smart cards were already well established in Europe, with French banks having recently ordered 3.5 million of the things from French-government-owned Bull.

During the crisis and while the take-over talks were ongoing, Popular Computing had concluded in an editorial that:

"It must be hoped that the Maxwell deal eventually comes off. The two companies have a lot to offer each other. Maxwell's information technology interests are considerable - both as an information provider and with licencing deals like his acquisition of rights to Drexler Technology's 4MB capacity optical ROM card. [However] the more protracted the Sinclair/Maxwell negotiations become, the less likely it is that a successful deal will eventually be struck. And all the time, the future of the UK's biggest volume micro manufacture is balanced on a knife edge"[72].

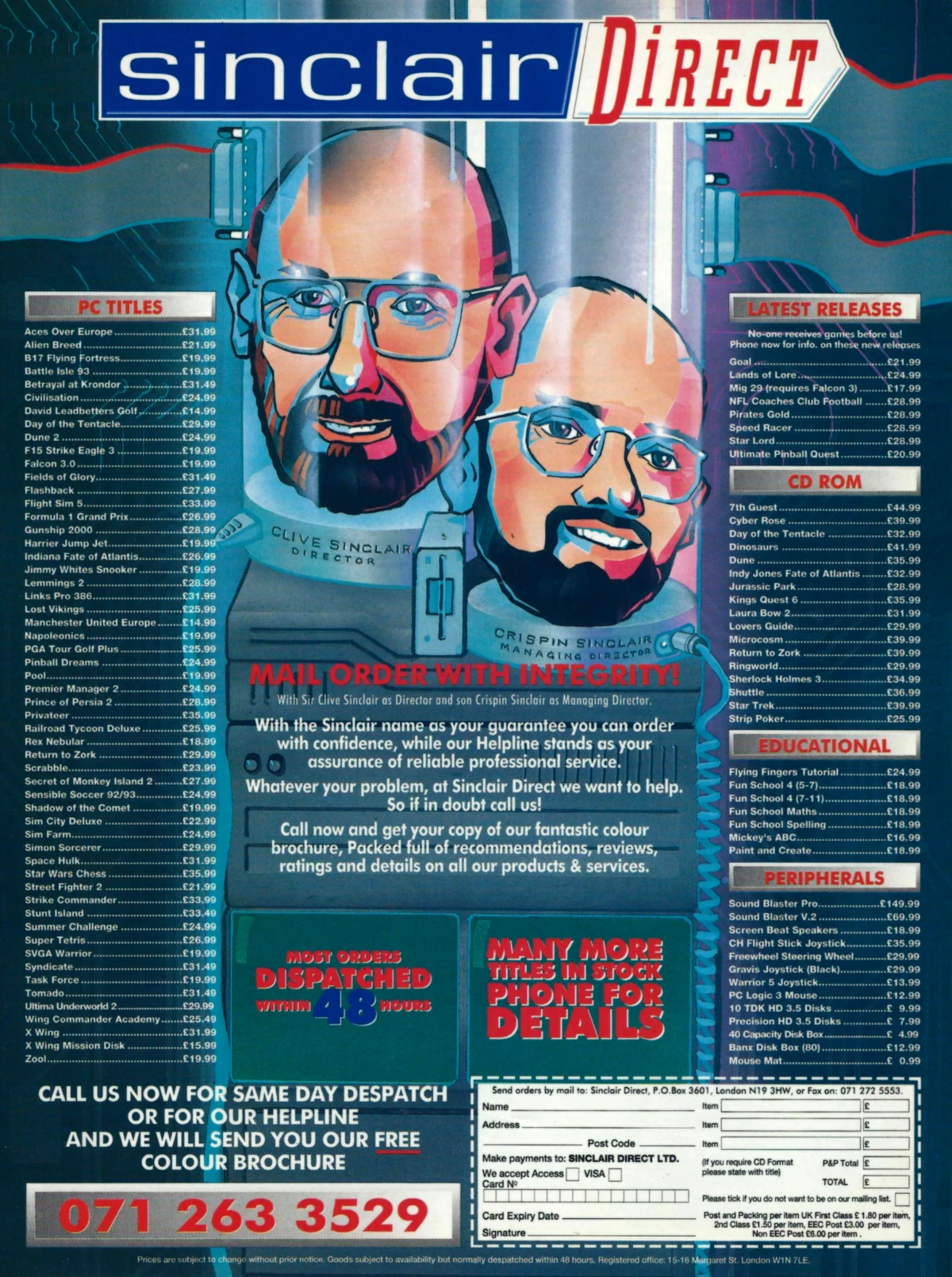

How the mighty have fallen: an advert for Sinclair Direct Limited, a company based in London and set up by Clive Sinclair, his wife Ann and their son Crispin - as managing director - in July 1993 and which launched in October of that year. It traded for a few years, but went dormant during 1997 having never apparently made a profit. From PC Review, December 1993

The End of Sinclair

In the spring of 1986, Sinclair's name and assets ended up being unexpectedly bought by Alan Sugar's Amstrad, in a deal worth just £5 million.

Clive Sinclair was left with the debt-laden Sinclair Research, which included his Metalab/Anamartic offshoot and to which he would soon add Shaye Communications as well as his own offshoot Cambridge Computer Limited.

By the beginning of the 1990s, Sinclair Research Limited was down to Clive and two other employees[73] - something of a fall from the total of around 130 in Sinclair's heyday.

Sir Clive continued with research into personal transport, with various forms of electric bicycle and the Sinclair X-1 - another go at an electric vehicle - but these projects either didn't make it to market or did not achieve any significant success.

On the 15th October 1993, he - along with his son Crispin Sinclair, ex-wife Ann and company secretary Patrick Hickey - launched Sinclair Direct, a mail-order company initially devoted to selling computer games[74] but which would eventually offer various computer peripherals and software.

The company never made a profit in its four years of operation, and was dormant by 1997[75].

Clive Sinclair died in September 2021, aged 81. According to his daughter Belinda, he was still working on his inventions just the week before "because that was what he loved doing[76]".

---

Robert Maxwell disappeared in mysterious circumstances from his luxury yacht "Lady Ghislaine" on the 5th November 1991 whilst sailing around the Canary Islands.

His body was discovered the following day, miles away from where it should have been[77].

Date created: 24 November 2019

Last updated: 15 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.