Sinclair Advert - 1984

From The Home Computer Course

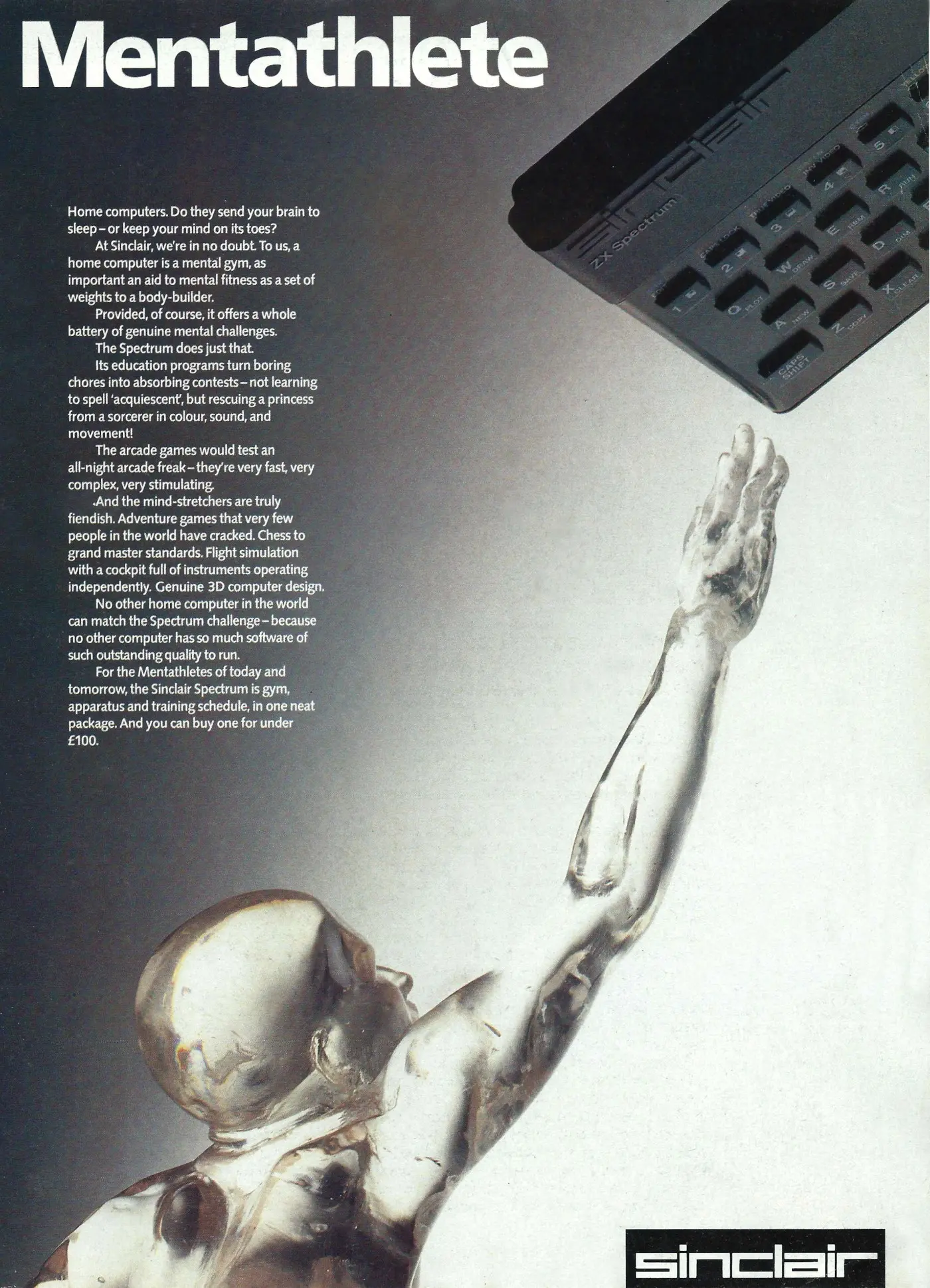

Mentathlete - the Sinclair ZX Spectrum

This is a slightly abstract advert for the ZX Spectrum, which appeared on the back of a home computer course. It shows an all-metal dude, like the T-1000 in Terminator 2, reaching up for the Spectrum, which is floating in space.

It adds "No other home computer in the world can match the Spectrum challenge - because no other computer has so much software of such outstanding quality to run".

The Spectrum had been launched in 1982, and in its various guises went on to sell over 5 million units worldwide[1]. It ran a 3.5MHz Zilog Z80A - a revision of the original Z80 found in many "generation 1" machines, like the Cromemco Z-1 of 1977.

The Z80 was itself an object-code-compatible "clone" of Intel's 8080 CPU, with enhancements[2].

In the summer of 1984 (the year of this advert), the contract to provide "the BBC Micro", which Acorn had previously won, came up for grabs.

Sinclair, knighted in the Queen's Birthday Honours list in June 1983[3], had long claimed that Acorn should not have won the contract in the first place as one of the stipulations was that the machine should cost £200 or less.

The BBC Micro (Acorn Proton) only managed to achieve that for a few months before the price went up to £300 and then £400, where it stayed for several years. Meanwhile, Sinclair's erstwhile contender, the Spectrum, had been on sale for less than £200.

As it happened, although some thought that official dislike of Sinclair himself had led to the Acorn being picked, the fact remained that the specification meant that the Proton was simply better suited than the Spectrum or ZX81.

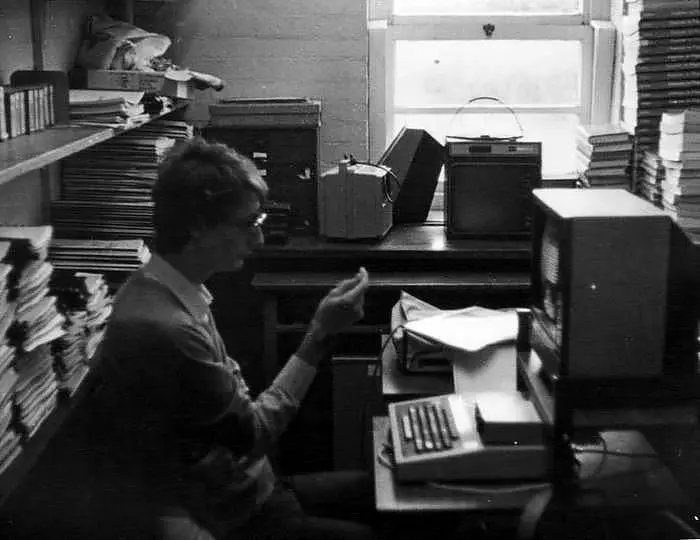

An Acorn Proton/BBC Micro in use in Brockenhurst College's Physics department, Hampshire, 1984Acorn's machine had a much higher resolution display, Econet networking and ability to load software over-the-air using the BBC's Teletext service, all of which were requirements of the contract. Last but not least was the Proton's robust all-metal construction and full-sized proper mechanical keyboard.

About the only thing Sinclair really had going for it was a proven ability to manufacture a lot more units than Acorn - Sinclair was selling 10,000 computers per month whilst Acorn was unable to fulfil demand as it shipped 2,000 Atoms a month[4].

Sinclair the company had started talking about its interest in the contract towards the end of 1983, with a spokesman saying "We would be most interested in competing for that contract if it is feasible for us to do so".

The company had already written to the BBC to find out if the contract was subject to open tender stating that "We want to state our interest openly, well in advance and find out how the BBC wants to handle it".

Maybe it also rankled Uncle Clive that Acorn was being quite flippant about the whole thing, implying that it thought that its renewal was "a formality", given how successful the project had been so far for both it and the BBC.

Acorn said "[we] are not at all worried - there is no reason why [we] should be - Sinclair tendered for the original contract and lost. We would be surprised if Sinclair had a product that would match up to the Acorn BBC machine. From Acorn's point of view the renewal is a formality"[5].

The complacency was in spite of (or maybe because of) some potential competition from other manufacturers as well as Sinclair, with Dragon Data's sales manager Richard Wadman saying that "we have indicated to the BBC that we would like to be considered for a bid", whilst Oric somewhat meekly stated "we would be delighted to be considered"[6].

There was also some more serious competition in the shape of lumbering behemoth IBM, which announced a £400,000 scheme at the beginning of 1984 to provide 92 selected universities and polytechnics with a free IBM PC[7].

However, when it came to Sinclair, it's really hard in hindsight to image an alternative reality where the small, plastic and rubber-keyed Spectrum would have made a better choice than the well-engineered, if expensive, metal-cased proper-keyboard I/O ports-tastic Proton in the schools, colleges and Universities of Britain.

Dr. Christopher Evans, author of The Mighty Micro, © Personal Computer World 1980Elsewhere, rumours persisted that ITV (the UK's independent commercial television network) was considering launching its own "ITV Micro"[8], with at least one of the ITV regions talking to Commodore about the feasibility of producing such a machine[9].

It was all a bit ironic really as it was ITV's television programme - "The Mighty Micro", based on Dr. Christopher Evans's book "The Mighty Micro: The Impact of the Computer Revolution" and broadcast at the end of 1979, shortly after Evans' death at the age of 48[10] - that has sometimes been credited with kick-starting the micro revolution in the UK and maybe even influencing the BBC to launch its Computer Literacy project.

However, at a meeting held in London on Monday, 12th December 1983, representatives of the independent television companies voted against a plan to offer a competitor to the BBC Micro, citing provisions in the Broadcasting Act which prohibited sponsorship, and a potential conflict of interest with its own advertisers.

The Independent Television Companies Association secretary Ivor Stolliday said "The debate has taken place at the most senior level and every company has come round - I think the decision will stick"[11].

Meanwhile, the Spectrum had been through several internal revisions, and by July 1983 the 48K model was up to Issue 3. This model featured a re-designed ULA (uncommitted logic array) chip which was used to control the Speccy's external ports.

Unfortunately, it updated how some of the I/O ports were handled and one port affected was the earphone port, the entry point for programs loaded from tape.

The change led to the wrong value being returned if a particular address was read: the value was different at bit 6, which used to be always set to high (or one) but was now low (or 0), although sometimes it would drift from low to high as the machine warmed up.

This could cause the program to crash, all of which, as rumours spread around the industry and even before many developers could even get hold of an Issue 3 machine, led to some software houses having to re-write their programs or provide extra checking software to cope with the fault[12].

Sinclair's software manager, Alison Maguire, followed up reports in the press a couple of weeks later by pointing out that programmers should have "masked out" (ignored) the top three bits of this address and were guilty of "unprofessional programming practices" and making "certain assumptions about the Spectrum which are completely unsupported and undocumented by us".

Although software houses weren't told of the change by Sinclair, she continued "Like any company, we can make changes to improve the product, changes that don't conflict with the manual we produce. Some programs that made that assumption have probably always gone wrong"[13].

This particular problem came back to haunt Sinclair a few years later after it had launched its Spectrum 128, when a steady trickle of software revealed that the 128 was "less compatible than first thought".

Once again, it seemed to be programming assumptions, in this case with some software houses making use of a chunk of memory just below the screen, which was different on the 128. Sinclair was "understandably annoyed" about this (once again), however it did appear to helping the companies involved fix their issues.

Melbourne House also found another incompatibility: all its games worked fine, unless a Kempston joystick was plugged in. Popular Computing Weekly helpfully suggested that Kempston owners either played games using the keyboard or got a new joystick[14].

Alison Maguire of Sinclair, © Popular Computing Weekly, August 1983Maguire's appointment to Sinclair in February of 1983 marked a subtle shift in Sinclair's attitude towards software, which previously relied on adopting a small number of software houses - perhaps most famously Psion - in order to produce software on its behalf under the "Sinclair" brand.

Maguire had been appointed to change this somewhat off-hand approach and to develop Sinclair's software side by seeking out more third-party programs to include, whilst clearly ruling out building its own team.

In an interview with Popular Computing Weekly, Maguire stated "Sinclair has never done and does not intend to develop its own software. The sort of skills needed to produce good software are not the same as those to produce the hardware, and I can see no point in establishing an in-house software development team which could become sluggish or lose its creative edge".

Sinclair's main worry wasn't games, for which its machines were already well provisioned, but educational software. The company had already joined up with Macmillan Education to publish ten titles, but its real agenda seemed to be the continuing struggle to break in to arch-rival Acorn's stranglehold on the UK education market thanks to its deal with the BBC - a situation Uncle Clive was known to be bitter about.

Sinclair was clearly optimistic that once schools had got used to their first machine - which was mostly the Acorn BBC Micro - they would be back for more cheaper machines.

Maguire continued "When [schools] come back for their second or third machines I am sure that they will be buying Spectrums. I don't know that we will ever take over from the BBC machine in schools, but I am very enthusiastic"[15].

The Spectrum was clearly in demand at this time - so much so that two lorries' worth of Spectrums were stolen in July 1983 whilst waiting at a TNT warehouse for distribution. Prism Microproducts, the distributor, had their schedules put out by a couple of weeks as a result, not least because they had to wait for police investigations to finish before they could access the warehouse again.

It was thought that around 3,000 Spectrums - worth over £300,000 - had been stolen, from a total stock of about 5,000 in the warehouse at the time[16]. Personal Computer News helpfully suggested that anyone being offered a cheap Spectrum should get in touch with their local police station.

A couple of months later, it was reported that 30 people had been arrested over the theft, which involved an armed gang gaining access to Prism's warehouse by staging a fake traffic incident and getting security staff to help them.

The gang was caught because the machines they stole were in fact non-functional and un-sellable, with police reckoning that about 90% of the missing stock had been recovered.

As it happened, Personal Computer News's suggestion was not that far off the mark as the stolen Speccies had been traced after they had been offered to computer shops that were usually supplied by Prism.

As Prism's Graham Daubney reported "Once the news had broken that the theft had taken place, shops became very wary about being offered Spectrums"[17].

In another sign that computers were rapidly becoming just another popular stealable commodity, Sanyo also reported the loss of 200 of its new 16-bit micros in transit between its Warrington warehouse and various dealers[18].

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 11 December 2024

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.