Sinclair Advert - July 1982

From Personal Computer World

New! Sinclair ZX81 Personal Computer

First appearing in May 1981, this is another common advert for Sinclair's ZX81 - the home computer which shipped with only 1K RAM, although Sinclair's BASIC was heavily tokenised and so it wasn't quite as bad as it sounded.

These adverts are quaintly optimistic, given the limited memory and the somewhat-tedious membrane keyboard that it inherited from the ZX80 - a situation which, by the summer of 1982, had led to a whole industry of better add-on/replacement keyboards, even though some of these ended up costing as much as a whole ZX81[1].

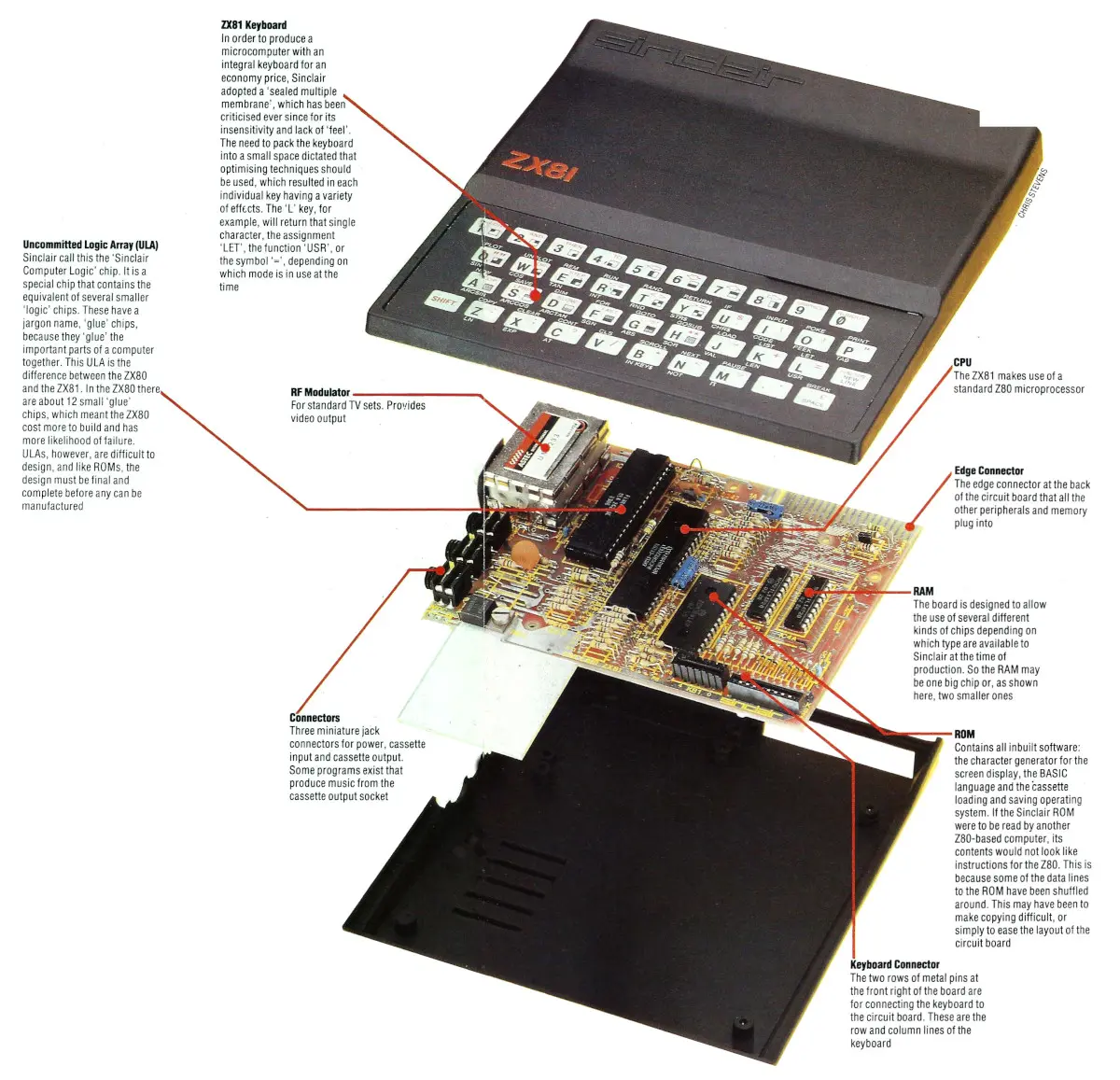

Gripes about the keyboard aside, Sinclair had done some impressive things with the internals compared to the previous ZX80, in particular reducing costs by getting the chipset count down to only four.

This was thanks to a single ULA - an uncommitted logic array - built by Ferranti and which replaced no fewer than seventeen of the chips that the ZX80 used.

This helped it to remain by far the cheapest home computer available in the UK - at the time its nearest competitors such as the VIC-20 were retailing for about £150 (£740 in 2026), or nearer £400 (£1,980) in the case of the BBC Micro.

By contrast, the ZX81's fully-assembled retail price of £70 is about £340 in 2026 terms, and even that was slashed to £50 (£240 in 2026) at the beginning of August 1982, following the release of the Spectrum.

Originally, dropping the price had been viewed by Clive Sinclair as being "not necessary"[2], but sales of the ZX81 did not hold up in the face of the, frankly, much better machine.

High-street newsagents-cum-computer-retailer WHSmith was said to have reported that "over-the-counter sales had dried up", and others suggested that sales had halved.

According to Sinclair, employing the same tactic in the US, where the price was cut from $150 to $100, had caused sales to "treble, actually".

Perhaps because - or in spite - of all this price-cutting, the ZX81 was still being sold up to 1984, at the price of only £45 (£190), which even included the 16K RAM pack[3].

However by the end of 1983 the machine had run in to some "major sales resistance", with the competition like Commodore's VIC-20 and TI's TI99/4A offering colour, more memory and proper keyboards.

This led to Timex, which was making modified versions of the ZX81 under licence for sale into the US, to slash the price of its TS1000 model to only $49[4].

The various rounds of cost-cutting didn't seem to have affected Sinclair's profits, which were reported in the summer of 1982 to have increased from £2 million to over £10 million - about £49 in 2026 - whilst turnover was also up to five times its 1981 level[5].

It was also reported that the company was managing to shift 20,000 units a week to the US alone.

At around the same time, it was announced that the ZX81 had become the first ever microcomputer to win a Design Council Award, which it won for bringing computers within the reach of the general public. The council's panel had concluded that:

"The price and easy-to-follow instructions mean that every member of the family can have the opportunity to learn about computers and how they are programmed"[6].

A nice exploded view of the ZX81, which appeared in 1983's "The Home Computer Course"

Nor did Sinclair seem too bothered about increasing competition, including the rumoured £50 Binatone 16K colour-and-sound micro, due on the high street by the end of December[7].

Binatone was not especially well-known for its technical innovations, but according to Gulu Lalvani, chairman of the company, it had "considerable experience of consumer electronics and retail pricing and marketing".

The erstwhile competitor to the ZX81 and Spectrum was expected to be manufactured and quality-controlled in the Far East and sold at a much lower markup than the ZX81, with Binatone planning to flood the market with more than 300,000 machines, selling via outlets like Rumbelows and Woolworth[8].

Perhaps luckily for Sinclair, Binatone's machine never appeared, whilst the ZX81 received a boost when a decision to sell it via direct mail to American Express customers resulted in 25,000 orders, of which 2,000 had been received by noon the day after the mailing offer had gone out. Amex was predicting final sales of over 50,000[9].

This went a long way to help offset continuing delays in shipping the Spectrum, which had been delayed following the discovery of a design fault in June.

The fault meant that only very few hand-modified Spectrums had been sent out, with major shipments being blocked pending a new batch of motherboards due in the middle of August[10].

The timing was fortunate as production was already suspended until August 3rd as the Timex factory, where the machines were produced, was closed for its annual three-week holiday[11].

Meanwhile, sometime around November 1982, Clive Sinclair - all-round tech visionary and head of British Mensa - was picked by the BBC to appear on its "Futures" programme. He produced some quite accurate predictions, including that the number of manufacturing jobs in the UK would fall even further.

At the time, traditional heavy industries like steel making, ship building and coal mining were already undergoing steep declines. He also said:

"we do not need a manufacturing industry to be wealthy... we must turn from the products of the material to products of the mind; books, video tapes, tv programmes, computer programs, design services, consultancy of all forms".

This was quite accurately summarised by Guy Kewney, writing in Personal Computer World, as meaning:

"we must become a nation of designers and let the low-cost-labour nations become producers"[12].

The UK hadn't quite got to the point of off-shoring every form of industrial production possible as the ZX81, and later on the ZX Spectrum, were still being built by Timex in Dundee.

In early 1983, there were industrial relations problems at the factory and the management was theatening to sack 1,900 of the workforce. Sinclair stated that if the threat was carried out and the remaining workers went on strike, they would "move our business elsewhere, probably permanently".

There were large stocks of ZX81 and Spectrum machines to cover any disruption, but it was thought that strike action could endanger production of the ZX83 - the code name for the up-coming "radically different" QL[13].

Perhaps some credence to this threat came when it was announced that Sinclair was shipping "small quantities of components" for local assembly in the People's Republic of China as a "trial process", with the hope that if it went well, Sinclair would be able to sell large numbers of ZX81s and Spectrums in to China.

This was despite the fact that it was thought that there weren't actually many televisions in China and the machine was the standard UK model, with an English keyboard and software.

However, it was seen as a way of extending the ZX81's life-expectancy, with Western markets saturated. Personal Computer News concluded:

"only cynics will believe that, after the trouble at Timex, Sinclair is not looking at China for large-volume, low cost, trouble-free production"[14]

Testing ZX81 keyboards at Timex in Dundee, © Sinclair User 'The First Annual' 1983The choice of Timex as its manufacturing partner was part of Sinclair's philosophy of sub-contracting out all of its factory production.

However, it was also a bold one as, up to that point, Timex had had very little experience in manufacturing electronics equipment.

At the time, Timex had decided to expand into new areas once it became obvious that its core market of mechanical watches, with it made at Dundee, was shifting to quartz and digital.

This drive for new markets led to discussions with Sinclair about producing its Microvision pocket TV, for which Sinclair had announced a £5 million capital investment programme over four years.

Timex didn't get that particular gig due to its lack of experience, but the discussions did lead to an agreement to produce the ZX81 instead, as a "first step in the learning process".

It undoubtedly helped that Timex was willing to put in all the capital investment - and training of staff - required to get the assembly line ready.

David Chatten, Sinclair's production controller said "Getting Timex to do the assembly on the ZX81 may have been a risky decision in the short term, but in the long term it provides us with considerable security, giving us the opportunity to build good working relationships before full production of the pocket TV begins".

It seemed to have paid off, at least at first, as by the end of 1982 Timex was producing some 60,000 ZX81s per month, up from 10,000 at the time of launch, whilst Chatten reckoned that Sinclair got:

"People who are good at manufacturing particular components [who] then get everything assembled in a good production plant. There is some room for improvement in the assembly process - perhaps greater use of automated production lines - but on the whole we are very pleased with Timex work".

Meanwhile, Timex seemed to reciprocate by using the micro it manufactured to test its own Nimslo 3-D camera[15].

Also in early 1983, figures for the sales of micros in the UK were published in Personal Computer World. These showed that 509,000 micros had been sold in 1982, of which an impressive 220,000 were Sinclair ZX81s.

The next-best-selling was Commodore's VIC-20 at 100,000, with other notables including the BBC Micro at 4th place at 40,000 units and the Dragon 32 in fifth place with 25,000 sales.

Micro analyst Robin Bradbeer published a report on the figures and reported that:

"Per head of population we have twice as many machines in the UK as the US and 1.5 times as many as Japan. Over two thirds of all PCs sold in Europe are sold in the UK. We also have more manufacturing than anybody else and are producing more machines"[16].

Bob Denton of Prism, © Popular Computing Weekly September 1983Sinclair continued to put out new software for the venerable '81 as late as September 1983, even though according to Personal Computer News the "ZX81 may be on its last legs in the High Street".

The autumn release included arcade games, puzzles and an IQ test - not surprising given that Sir Clive was the president of Mensa.

At the same time, a machine-code Monitor/Disassembler as well as the Zeus Assembler, both part of Sinclair's software development drive - described by managing director Nigel Searle as "a high priority" - were released for the Spectrum[17].

There had also been a surge of software for the ZX81 in October 1982, when the machine's distributor - Prism - branched out from its distributor-only roots into cassettes.

The increased range included titles from other leading software developers, largely because Prism had been actively touting for programs from other companies to sell, as it had access via its distributor network to a large number of outlets that many software companies could not normally reach. As Bob Denton, Prism's managing director said:

"it is no longer mail-order, it is retail. We have written to everybody who, as far as we know, has produced material for the ZX81 and many have submitted samples to us. Any software passing our quality assesment will be included to augment the Sinclair catalogue".

Mark Eyles of Quicksilva concurred and pointed out the change in the ZX81's status:

"The ZX81 is now a true High Street microcomputer and we get very few cassette mail-orders now. If the ZX81 is to be sold in newsagents then that is where we want our tapes"[18].

Quicksilva had only the week before reduced the price of its best-selling '81 software, a move which Popular Computing Weekly thought might be the start of a cost-cutting avalanche. Eyles said of the discounting that:

"We have cut the costs of the cassettes to keep the ZX81 market going. There was certainly a lull in software sales after the Spectrum launch so these price drops should make it a bit more healthy"[19].

---

Popular Computing Weekly noticed at the end of July 1982 that Sinclair Research had just reached the count of 42 staff, a number which happened to be the answer to the the "life, the universe and everything" question posed to computer Deep Thought in Douglas Adams' Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy[20]. A bit ironic really, given that Adams was a die-hard Apple fan.

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 13 February 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.