Sinclair Advert - November 1983

From Electronics and Computing Monthly

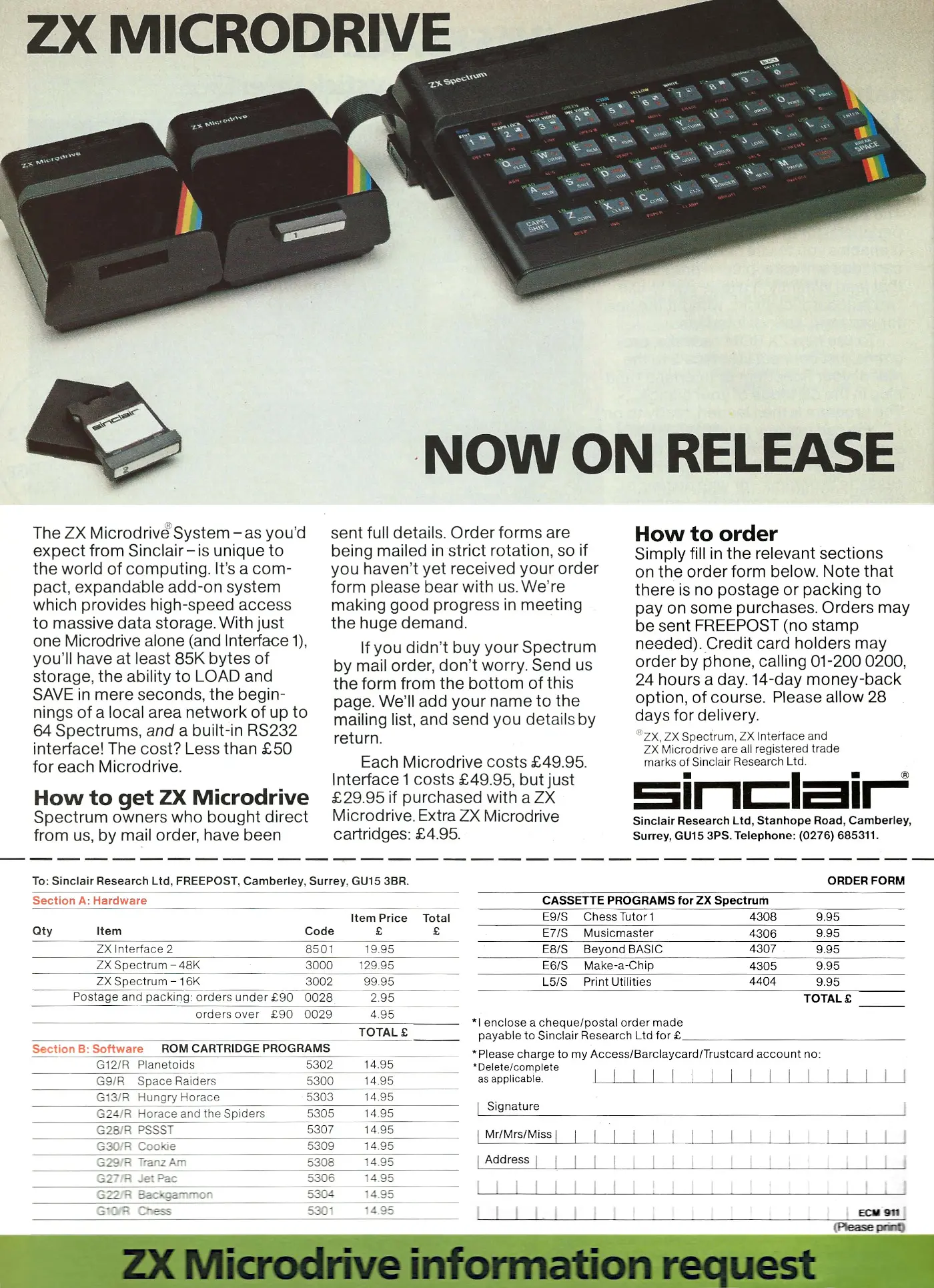

ZX Microdrive - Now on release

Sounding something like a statement on the fate of a serial murderer from a top-security prison, this advert, which was part of one of Sinclair's regular "mini magazines" within the magazine they were placed in, trumpets the arrival of the ZX Microdrive, a year after they were first announced.

A Microdrive required the Interface 2, announced at the same time at the Personal Computer World Show[1], or the two-month-older Interface 1, both of which also gave the Spectrum some networking capability and a built-in RS-232 interface.

The fact that it took the Microdrive around a year to appear was unfortunate, in an ironic kind of way, as Sinclair had been quick to bash the practice of "kite flying" - announcing the next-best-thing since sliced bread way before it was actually shippable.

"Not a figment of our imagination"

In an interview with Practical Computing back in the summer of 1982, Clive had suggested that Sinclair did everything on time, to very tight schedules and with a great deal of commitment.

"There is far too much [kite flying] and it is very silly. It mucks up the market-place all the time but it rebounds on the company eventually".

Suggesting that these "other" companies were amateur because they were always talking about their mythical products that were ever further away, Clive continued "If we announce a product now, it is because it is ready for production".

He then went to suggest that the Microdrive was miles ahead of what anyone else was doing and was "not a figment of our imagination - we have that working you know".

Sinclair also dropped some hints about what would become the fabled "Pandora" - a laptop machine that was intended to combine the Microdrive, the company's flat-screen technology developed for the Microvision TV, and its 4"-wide thermal printer, all of which would apparently come together to produce "a much handier package than, say, an IBM system".

Instead of the "suitcase full of bricks" which was the barely-luggable Osborne One - its probable competitor - Sinclair's machine would be "Maybe a couple of pounds in weight - say two to four to be on the safe side"[2].

Sinclair had long been cagey about the exact nature of its Microdrives, and for some time even referred to them as "microfloppies" - when discussing the Pandora he even suggested that the machine would have "dual floppies - Microdrives that is".

However, despite the name, the Microdrive was actually a "stringy floppy" - a serial-storage device which utilised a loop of tape running at high speed, and not actually in any way a "floppy disk drive".

At first, they were recieved favourably, with Personal Computer News writing that they had been "worth the wait"[3], but fragmentation of often-used files made access slower and slower over time. By the time Microdrives were used on the Sinclair QL, they had become a liability.

Microdrive Hotline

When the first Microdrives were made available to customers, those that had been the first to buy the Spectrum became the first to receive priority order forms, on the day of the launch, with a limit of two drives per customer.

The first 400 Microdrive customers also got access to a special hotline telephone number, direct to one of Sinclair's engineers in Cambridge.

Needless to say there were several issues with the new technology, as described in an analysis of the Microdrives by Andy Pennell, writing in Popular Computing Weekly. It was discovered that Issue 3 Interfaces would crash with a Microdrive connected to some Spectrums.

Then there were problems with the tape mechanism, including total seizures of the cartridge and instances when the tape would snag on the pinch-wheel and become hopelessly wrapped around it, jamming the cartridge and rendering it useless. The latter fault was, according to Sinclair, a "design fault" which by then had been corrected.

Also problematic, although not really a fault, was that each Microdrive - and up to eight could be chained together - took 600 bytes of user RAM, meaning that any commercial software that made full use of the Spectrum's memory would not run[4].

Another major issue was that different Microdrive units ran at different speeds, so that data recorded on one was unreadable by another. Pennell's call to the hotline resulted in the response that it was a "known problem, with no easy solution", although Sinclair did offer to take the drives back and supply two that matched. Sinclair's managing director Nigel Searle later denied that such a problem existed.

Even worse was the problem where saving a BASIC program that was too big revealed a bug in the Interface's ROM which caused a crash that left the Microdrive motor running, requiring the pulling out of the power supply, which often damaged the tape and led to lost data. Sinclair was "working on it".

Microdrive "tapes" also had no official guarantee of lifetime and were expensive, with bulk discounts only available for orders of 500 or more, which at the time of the review was about one tenth the entire user-base of Microdrive owners, although no-one at Sinclair was actually allowed to say how many Microdrives there were in existence.

Perhaps the final insult was that in true Sinclair style, Microdrive cartridges were only available mail-order, subject to Sinclair's infamous "28 days delivery"[5].

Moving slowly

Some three months after the launch, the Microdrive was still in short supply. Still working its way through the backlog in strict order of original Spectrum purchase, the company admitted that it was "still very near the top of the list".

Despite that, Sinclair did report that it was happy with the take-up amongst Spectrum owners, saying "the drive has been greeted with enthusiastic response".

Meanwhile, the arrival of the first commercially-available software for the drives looked to be moving further in to the future.

Psion, with its close association with Sinclair, was thought to have been a likely candidate to be one of the first companies to specifically support the device, but revealed that it wasn't planning on doing so until 1984. Psion's David Potter said:

"The problem at the moment is not the Microdrives themselves but a shortage of blank micro cassettes. We would need hundreds of thousands per month to meet demand and Sinclair's subcontractors are the only people with the sophisticated machinery to manufacture them"[6].

Although the Microdrive was heralded as somewhat revolutionary - if non-standard - the idea was not a new one. Exatron, a Santa Clara, US-based company, had been selling String Floppy "wafers" back in 1980 for S-100 and SS-50-bus machines like the SWTPC 6800 as well as the TRS-80, with an intention to also offer PET and Apple versions.

Exatron's version promised 14,400 bits per second and an error rate of 1 in 100,000,000 bits with an average life of 3,500 hours for the transport mechanism. Each "wafer" offered storage of 40K and the drive retailed for around £200, or about £1,310 in 2026 money[7].

Sinclair's Pocket Flat-Screen Television

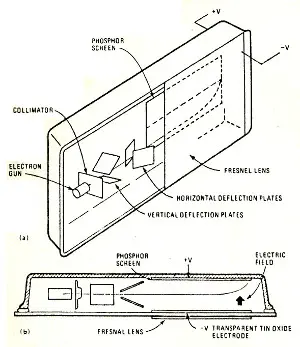

Sinclair Flat CRT Schematic, © Electronics and Computing, April 1983Just a few months earlier than all of this, Sinclair published the first details of its flat-screen TV technology - a product which it was hoped would provide the display for its future "Pandora" portable, and even originally the display for what was to become the QL.

None of these forecast uses came to pass, and after Sinclair had sold off the company to Amstrad and had started again with the Z88 portable, he admitted that the whole flat screen diversion was:

"very good, but it couldn't quite give us a display 80 characters wide. We went up to about 66 characters but couldn't do any better"[8].

The technology was interesting, although the concept for flat screens dated back to designs published by Dennis Gabor of Imperial College, London and William R. Aiken of Palo Alto in the 1950s[9][10].

Other companies like Texas Instruments and RCA had all attempted flat-screen CRTs, but Sinclair and Sony's designs were considered the best at the time[11].

Sinclair's version was the end-result of six years' development, at a cost of some £4 million, and was eventually unveiled in London in the week of 15th September 1983, with Uncle Clive saying it was:

"A major breakthrough. I believe it, and its successors, can achieve for television what the transistor radio did for wireless"[12].

Sony ended up beating Sinclair to launch its own pocket Watchman TV first, a situation partly caused by industrial-relations problems at Timex's Dundee plant where much of Sinclair's stuff was made.

Even so, Sinclair's unit was smaller and cheaper than Sony's, which was expected to cost around $200 in the US, whilst Sinclair's Microvision was available for £79.95, or around £360 in 2026[13].

The race was on though, as Matsushita of Japan had already announced that it was developing a portable colour television. Sinclair was also looking at colour pocket TVs, but the company wouldn't commit to any completion dates.

The news of impending Japanese competition was worrying Sinclair as its dispute at Timex entered its seventh week. The sit-in by 350 workers was organised to protest against proposed redundancies at the Milton, Dundee plant, but the action was holding up the flat-screen tv production line.

At the end of May, workers had rejected a new 10-point plan offered by Timex, which included a promise that there would be no compulsory redundancies for 90 days, however unions wanted agreement on re-allocation after that time.

Sinclair said that the rejection of the offer was "very serious" and the company was continuing with its legal moves to evict the striking workers[14].

Sinclair's tube worked by placing the cathode ray source to the side and passing the beam through deflector plates and an electric field that deflected it on to a phosphor screen, rather than the viewer seeing the dots as they are projected on to the back of a phosphor screen printed behind the glass screen as in a conventional TV.

Sinclair claimed that this gave a brightness gain of more than double. The drawback of this horizontal arrangement was that the dot stretched elliptically along the horizontal axis and towards the top and bottom of the vertical. To counter the vertical problems, a fresnel screen was placed in front of the phosphor screen, with some electronic compensations being made to also fine-tune the shape of the dot.

The whole tube was manufactured as two sheets of glass vacuum-formed in to a boat shape, with the top sheet of glass being covered with a transparent conducting repeller electrode and the phosphor being dry-electrostatically deposited on to vacuum-deposited electrodes on the bottom sheet[15].

The TV was powered by special flat Lithium batteries that had been developed in conjunction with Polaroid. They weren't especially cheap, working out at around £10 for three which, given that each lasted about 15 hours, meant a viewing cost of 23p per hour, or about 70p in 2015.

Sinclair's TV was also multi-standard and could work anywhere in the world - except France, Russia and China - which meant that the TV could be sold in one design almost anywhere, which was important as all the electronics on the device were combined in to a single custom-designed Ferranti IC, developed at great expense[16].

The miniature flat-screen TV eventually launched as the "Microvision", although it didn't sell particularly well, probably for the same reason that true mobile TV - as opposed to crappy 30 second videos on YouTube - has never found a significant audience even in 2025, and Sinclair certainly never achieved the 1,000,000 tubes per shift off its Timex production line that Sinclair had optimistically forecast back in 1982[17].

The company even resorted to chucking them in as a freebie with an offer to refresh Spectrum+ sales, as reported in July 1985's Your Computer[18], which was somewhat optimistic as with its screen size of 1½" x 1⅛" (3.8cm x 2.9cm) it was a little on the small side for spreadsheet use.

It also didn't have an external aerial socket, but that didn't stop people trying as, according to Popular Computing Weekly, it was possible to wrap a wire from the micro's RF modulator around the aerial and tune it to Channel 36.

Perhaps surprisingly though, this hack revealed that "despite the small size, Tasword 2's 64-column screen was almost legible - the tube has good resolution". The review added:

"Considering the technical achievement of cramming a multi-standard, flat-screen TV into such a small space, the results are remarkable"[19].

About two months before the company (or at least its name and assets) was sold to Amstrad in 1986, Sinclair announced that it had sold all the marketing and distribution rights to the TV to its Dundee manufacturer, Timex, with the deal expected to contribute to easing Sinclair's ongoing financial crisis, from which it was still slowly recovering.

Although this meant that Sinclair would have little further involvement with the Microvision product itself, it was intending to continue with research into flat-screen technology, as it was still hoping to use some derivitive in the fabled Pandora portable. A Sinclair spokesdroid summed it up as:

"Flat screen technology was always intended to be used in Sinclair's computers, as indeed is the wafer-scale research. Odd products - that is those that are not part of the original long-term plan - can then always be released from that research. The pocket TV was one such opportunity"[20].

At the time, Timex was planning to release an additional export version, with UHF and VHF facilities (Australia, for example, used VHF until at least 2017 for rural transmissions[21]) as well as chopping the price from £100 to £80.

Arise, Sir Clive

Back in September 1983, and in non-flatscreen-tv news, Sinclair announced that its pre-tax profits for the year to March 31st 1983 had nearly doubled to £14.03 million, up from £8.55 million. Turnover had almost exactly doubled to £54.53 million and earnings were up from 106p to 207p.

Sinclair's chairman, now known as Sir Clive, stated that the figures were "encouraging", but went on to admit that the company had been facing challenges:

"In particular the US market has been badly affected by a price war since Christmas which has driven the market leaders [Commodore] into heavy losses and resulted in a much lower sales volume in money terms than we expected. Fortunately, the UK market proved better than anticipated which partly compensated".

Referring once again to the flat-screen TV project, Uncle Clive said:

"We expect to be leaders in the flat screen television field where we are confident that we have the best technology"[22].

Clive Marles Sinclair had become Sir Clive in the Queen's 1983 Birthday Honours List. He said at the time:

"It was completely unexpected and a wonderful surprise - more than ever I find myself committed to achieving success here, and for, Britain".

Sinclair the company had risen to become the world's biggest computer company by volume and in January 1983 had been valued at £135.9 million, with Sinclair's own holding worth £129.1 million - that's around £580 million in 2026.

Expansion plans

The company also announced a tentative move in to China following a visit by Nigel Searle to Shanghai and Beijing in August to discuss the feasibility of setting up assembly lines to manufacture the Spectrum and ZX81, under the watchful eye of the South China Computer Company and the China Electronics Import and Export Corporation. A Sinclair spokesman stated:

"Sinclair has now shipped small quantities of ZX81 and Spectrum components for local assembly and sale in China, on a trial basis. It is hoped that, if this initial trial is successful, it will lead to larger quantities of Sinclair personal computers being sold in China over the next few years".

There was some reason for optimism as the Chinese had already "earmarked" a factory in Guangzhou and the Beijing Software Academy was working on Chinese characters for the Spectrum.

There was also some interest in Micronet 800, the microcomputer-focused part of the Prestel dial-up Viewdata service. Richard Hease and Bob Denton of Prism - Sinclair's distributor and developer of Micronet - were also in China in August to discuss setting up a similar Micronet-like service[23].

A month later, and broadly coincident with arch-rival Acorn's news that it had purchased ICL's Computer Education software team, Sinclair announced a tie-up with book publisher Macmillan in order to develop a new range of educational software.

Five of the nine titles had been developed from Macmillan's best-selling primary school reading scheme by the Centre for Teaching of Reading at, confusingly, Reading University, with more titles due to be announced throughout the following year, although all of them were so far for the 48K Spectrum only.

The former Conservative prime minister and owner of Macmillan, the Right Honourable Harold Macmillan, then aged 90, said at the launch:

"In my lifetime the powers of distributing information have grown in a way that could not have been dreamt of in my youth: radio, television and now the microcomputer. Whether it is to the benefit of mankind is for you to decide. We want to see if, with the combination of Sinclair and my company, we can produce something of real value in the actual work of education"[24].

Date created: 11 August 2014

Last updated: 28 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.