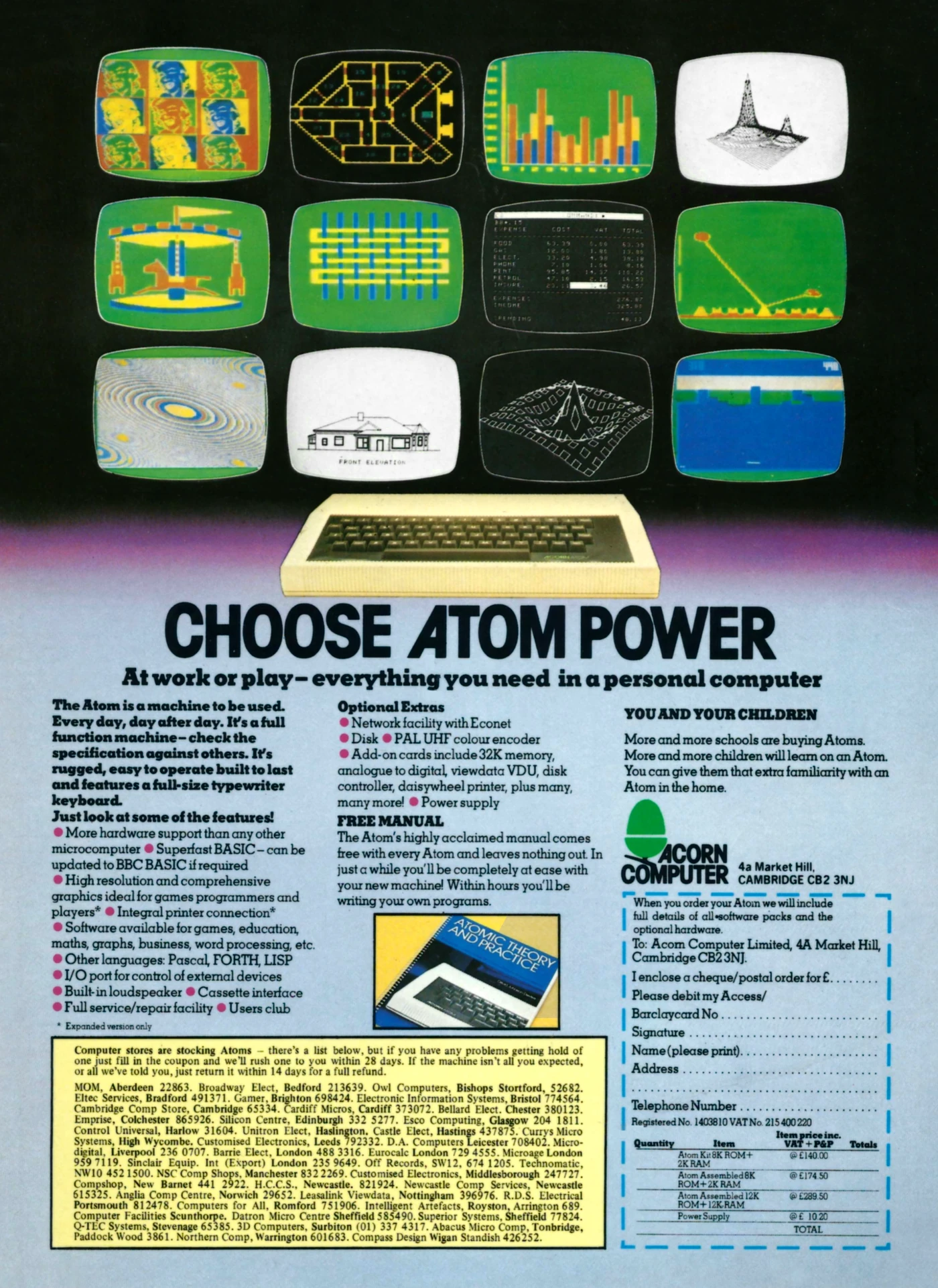

Acorn Advert - November 1981

From Your Computer

Choose Atom Power

Right on the cusp of Acorn's launch of the Proton - the computer better known as the BBC Micro - comes this advert for its existing Atom, the 1980 machine which evolved from the even-earlier System 1, launched in 1978.

The much better-specced Proton was not intended to replace the Atom, with Acorn seeing the two as supporting different market segments - not least as the entry-level Atom at £140 (around £770 in 2026) was well under half the price that the Proton would end up retailing for.

Instead, Acorn continued selling the Atom until the release of the Electron - a computer pitched as a cut-down and affordable BBC Micro which was first announced in 1982 but which didn't ship in serious quantities until the end of 1983.

The Proton became the BBC Micro because it ended up being chosen as the computer to support the BBC's Computer Literacy project, which was launched in the late summer of 1981, although apart from a trickle of machines, Acorn didn't actually manage to produce it in any meaningful quantities until early the following year.

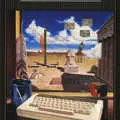

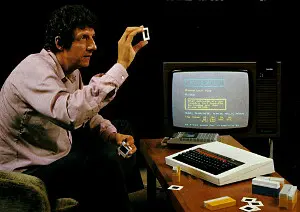

Chris Searle and a BBC Micro on the front cover of "The Computer Book", which accompanied the Computer Literacy Project. © BBC Publications, 1982As a result of the late delivery, the BBC ended up having to postpone some of its programming until later in the year, although they were shown as scheduled early in the mornings and in schools.

The Department of Industry also became involved in the project and offered subsidies to schools which didn't yet have a computer so they could buy either a BBC Micro or Research Machines' 380Z at 50% of the cost.

At the time of this advert - before the BBC Micro was officially launched - Acorn hadn't yet made much of an impact on the education market, although it was selling some computers into schools, with the claim that "more and more schools are buying Atoms".

However, it was very much in the minority, with a July 1981 survey published by the group Microcomputer Users in Secondary Education (MUSE) suggesting that there were only 59 Atoms in secondary schools, compared to 579 Commodore PETs and 702 Research Machines 380Zs.

Nevertheless, with a mix of Commodore, RM, Acorn, Tandy, Sinclair, Nascom and even Apple - and partly thanks to the government scheme - nearly half of secondary schools already had some sort of computer, which was over a 100% increase from 873 computers in 1980 (according to a Council for Educational Technology survey) to 1,848 in 1981.

Despite the increasing presence of computers, there was often no particular application in mind - some schools would use their computer to teach programming, whilst others viewed it simply as an additional classroom aid, like an overhead projector or some laboratory equipment.

This led to sometimes pessemistic views as to the usefulness of computers in education, including, as Your Computer suggested in a December 1981 article, the idea that:

"schools' computers will follow the 1960s' teaching machines into oblivion, leaving hardly a ripple behind"

However, there were of course utopian views around as well, such as:

"At the other end of the spectrum are the visionaries who see schools reduced to social development or 'play' centres. Learning would, they say, take place at home or in small units under the management of computers with little human intervention[1]".

As well as the Department of Industry's scheme - sometimes referred to as the "DoI half-micro scheme" - the government had previously set up the Microelectronics Education Programme (MEP), with a spin-off known as Microelectronics in Schools (MIS), funded with £9.5 million in 1979 terms, or around £66 million in 2026.

With a wider remit than simply computers, the MIS scheme also hoped to address the other issue prevalent at the time - the lack of teachers who actually knew anything about computers in the first place.

According to head of the project, Richard Fothergill, this was the second pillar of the MIS scheme, where:

"We train teachers to think of the computer as an instrument. We show them how it can revolutionise the office - indeed part of the teacher-training programme is devoted to familiarising teachers with the electronic office. We also train the teachers to use the computer for computer-based learning [as well as] in technology. There is a course in control technology and electronics [which] takes in just about everything from the switching of one transistor right up to control devices and beyond into the world of microcomputers"

The project also helped withn curriculum development, including supplying appropriate books and film resources, and also provided in-service training to teachers via the Open University.

There was some overlap with this and the DoI scheme, with MEP offering to train teachers from schools which purchased their micro using the 50% discount, providing two teachers with four days of on-the-job training on whichever of the two computers was chosen.

This somewhat limited choice - between the Proton/BBC and the 380Z - was a pragmatic one, as the government only wished to subsidise British computer manufacturers.

Fothergill said of this situation, in an interview in December 1981's Your Computer, that:

"Under the circumstances, this is as good a selection as could be made. The Acorn Atom has a proven track record, the BBC machine will be in a form that is bound to be successful. The 380Z is a machine which is well-proven in schools and is a solid machine - it can take the treatment the schools will give it"

Conspicuous by its absence from the list of approved suppliers was Sinclair, which at this point in time had shipped both the ZX80 and ZX81 micros - both at a price significantly less than Acorn's Atom, never mind the Proton - and which, unlike Acorn, had a proven record in producing computers at volume.

However, the ZX81 never really met the spec, and Sinclair wasn't amenable to changing it to match. With its small size, lack of decent expansion, plastic case and membrane keyboard, it would not have stood up to serious use in a school environment.

That said, Sinclair - at least as a potential choice as the BBC Micro - had its supporters, including Paul Johnson, one of the founders of Tangerine.

Tangerine had also been approached by the BBC, but had been ruled out as the TV programme's producers were not convinced that Johnson and his team could produce a suitable computer in time, a decision which Johnson reckoned was "fair enough".

Besides, the company wasn't keen to have 12,000 micros sitting in a warehouse waiting for the broadcasts to start, nor was it keen to take on giant companies like Commodore, which Johnson considered as likely to push hard for the BBC gig. He continued:

"The BBC should have chosen the ZX81. The [TV] series is a good idea, but the approach is wrong. The BBC should have planned a first series on the ZX81 and if it was a success and people wanted to move into larger systems, it should have then planned another series[2]".

Meanwhile, Fothergill concluded his Your Computer interview with a view that:

"Education today is at a crossroads, what we have now is a period of transition. For the first time the majority of schools have micros. In a year or two schools will have several more machines which will be scattered around in different departments - we are on the verge of an explosion[3]".

The BBC Micro eventually became very successful in education, thanks in significant part to its use in the BBC's Computer Literacy programme, even though Acorn's Chris Curry frequently downplayed the importance of that market, saying in 1982:

"The education market for us has been quite a small proportion of our business; so far it hasn't made a lot of difference"[4]".

The BBC Micro sold around 1.5 million units, whilst its BASIC - written in-house but loosely compatible with the de-facto standard Microsoft BASIC - became a standard in UK education.

Eventually though it faded away against the hegemony of the IBM PC and its MS-DOS operating system, as well as suffering from the wider move away from computers as a programming tool to computers as a tool for word processing, presentations and spreadsheets.

Date created: 08 November 2025

Last updated: 09 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.