Research Machines Advert - May 1979

From Personal Computer World

The Research Machines' 380Z - A unique tool for research and education

From its launch in 1977 through to mid 1982, Research Machines Limited, often abbreviated to RML or RM, seemed to be selling the same one machine - a Z80-based system called the 380Z, or rather 380Ƶ as RM liked to print on the micro itself.

It was first advertised under the "Sintel" banner in early 1977. Sintel was an offshoot of RM that had been set up in 1974 in order to provide a reliable funding stream from mail-order electronics kits and components[1].

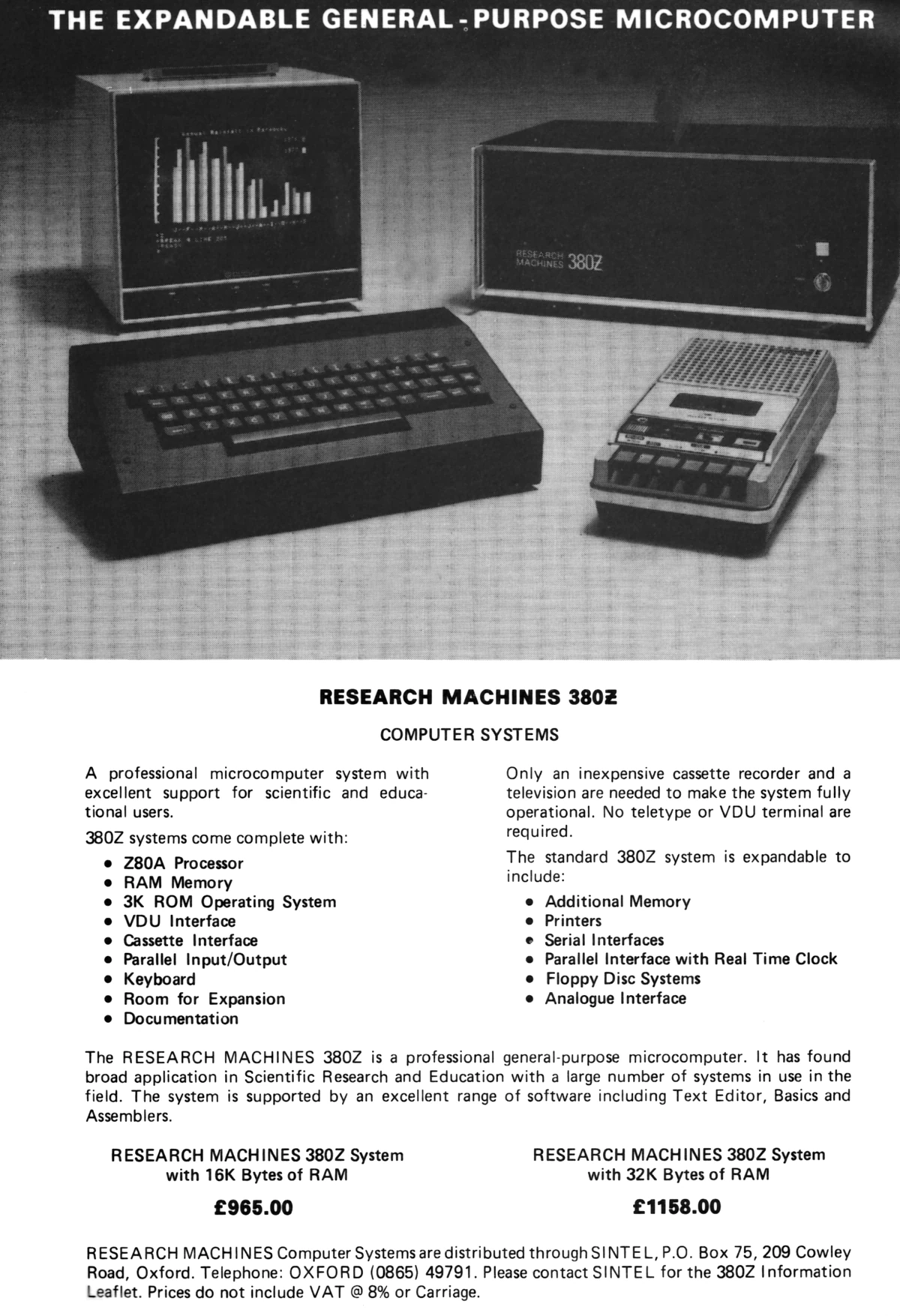

An earlier advert for the 380Z from July 1978's Personal Computer World, showing the machine being distributed through Sintel of Cowley Road, Oxford, just round the corner from RM's own address of Chapel Street. Telephone nerds might spot that Sintel and Research Machines had adjacent phone numbers. Note also that 16KB system is selling for the same face-value price of £965 as in the later advert. The high rates of inflation at the time mean that the system was actually about 10% cheaper in real terms just a year later, although an increase in VAT offset some of that as the rate changed to 15% from 8% in 1979.

The first prototypes were released in August of 1977, with production models appearing from December, making it one of the first British micros to go in to production[2].

It came in a base-unit-and-keyboard configuration, ready to plug into a handy black-and-white television or monitor, as the advert shows.

With a single floppy system retailing for £1,930 including VAT (about £14,300 in 2026 terms) - or the dual FDS-2 system in the advert at £3,266 (£24,200) - it was very much priced for the education and research market.

However, for the budget-conscious, there was also a little-advertised £400 (£3,210) version, consisting of just the CPU and VDU boards, called the 280Z.

The machine reviewed very well in April 1978's Personal Computer World, with Mike Dennis concluding that

"the product was excellent - the boards really are a work of art - and there were many innovative and ingeneous design features. Much thought has gone in to the design to make it as flexible and easy to interface to as possible. Any business, firms, institutions, schools, etc, considering buying a good all-rounder could do a lot worse than take a long hard look at any of the RML [machines]"[3].

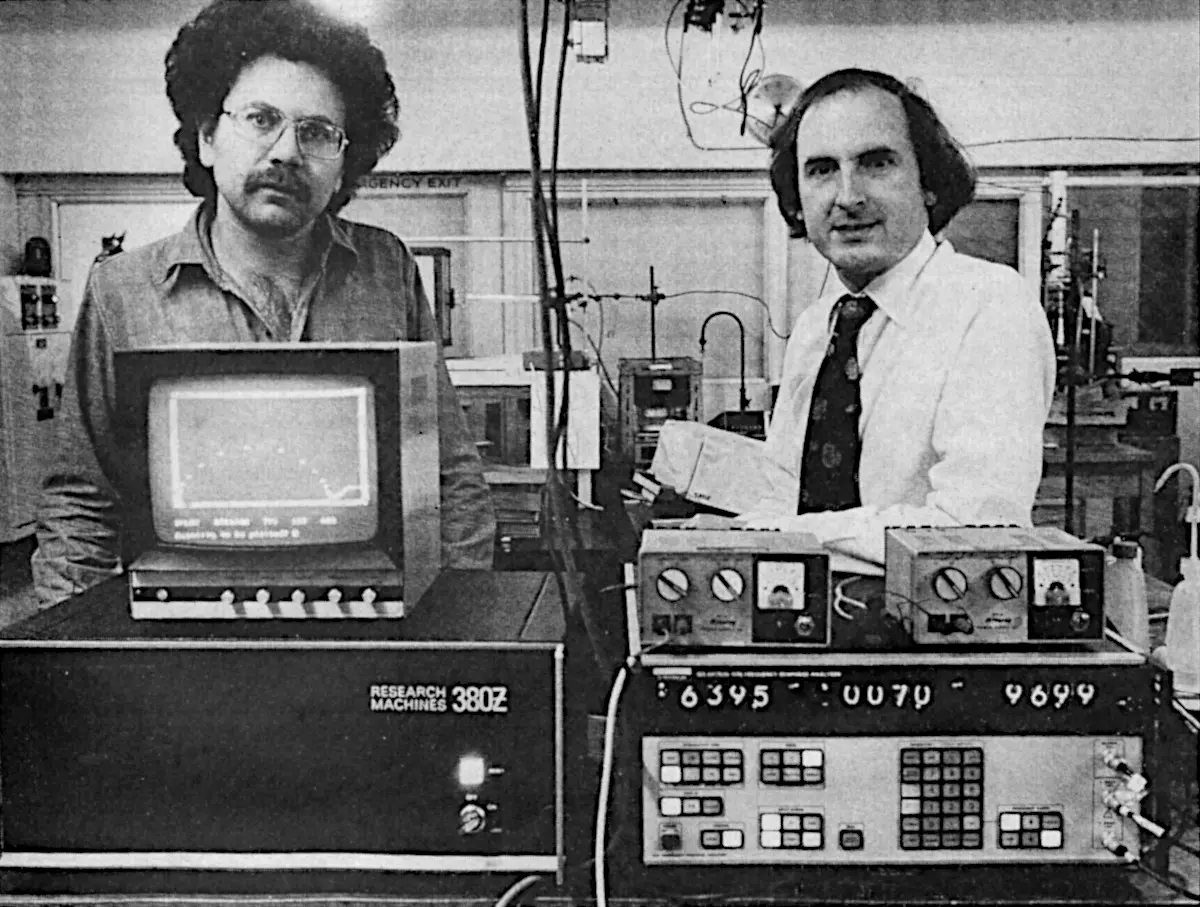

An RM 380Z in use by Nicky Bonanos and Dan Waters at the Royal School of Mines in London. From Practical Computing, August 1980

Almost as soon as appliance computers had appeared towards the end of the 1970s, they were being seen as a de-facto solution to educational problems, even though improving education is far more a social/political issue than it is a technical one.

Technical problems are easy, given enough resources, but the question was often asked "How can we go to the moon when we can't design a better curriculum or provide a better healthcare system?"[4].

Furthermore, there were also worries that much of the early focus, where there was any, seemed to be a teacher-centric one which:

"takes as its model the activities of the classroom teacher - presenting information, testing, supervising drilling-and-practice and keeping marks", rather than trying to develop a more child-centred approach which would allow pupils to use a computer as "a powerful tool with which to explore and manipulate the world".

Towards the end of the 1970s, the Labour government had started formulating an action plan to meet the challenges of new technology, which following a change of government in 1979 was eventually launched by the Conservative government as the Microelectronics Education Programme, or MEP.

The worry was that the "current orthodoxy" of the £9 million programme - first announced in March 1980 - would ossify and be unable to respond to the rapidly-changing educational needs of the real world, as it by neccessity had laid down a rigid framework for evaluating potential projects[5].

When microcomputers first started appearing in schools, there was a significant lack of coordinated policy, with central government and local education authorities clearly ignorant of the impending revolution, and teachers "sensing the value of computers as a teaching aid" but lacking clear guidance on how to make use of them, and for what[6].

This also meant that instead of central purchasing, each school was buying whichever random machine the one teacher in school who knew about computers had recommended, or one from whichever manufacturer made the most persuasive sales pitch.

The BBC's Computer Literacy project of 1982 - which coincided with a change to MEP to include primary schools for the first time - could be seen as one attempt to sort this out, as it ended up putting the BBC Micro in many schools and led to the mandating of the BBC, Research Machine's 480Z and Sinclair's Spectrum as the only choices if schools wanted to make use of 50% grants available throughout the early 1980s[7].

There had already been much controversy over the choice of Acorn's Proton as the official BBC machine, as it had been said that the original specification was tailored to favour RM's 380Z, or the original choice - Newbury's NewBrain machine.

Sinclair was also scathing, and lobbied hard to get its Spectrum included as part of the scheme, although in November of 1982 it was reported that only three of the 422 applications that month were for Sinclair's machine[8].

Elsewhere, and perhaps more optimistically, education also seemed to be capable of enabling humanity to become "one" with the machine.

Writing in Personal Computer World in the Spring of 1978, product developer for Intel, William "Bill" Ringer, suggested that:

"as a consequence of microprocessor technology, we are now about to witness another revolutionary step forward. Our future generations will not only have the ability to read, write and perform arithmetic but also to express relationships and solve problems through languages of logic. Most commonly, everyone will be familiar with at least one programming language. Only through the widespread popular understanding of the languages of logic can we protect our personal values and rights from the encroachments on those freedoms resulting from programmed implementations of laws and procedures by narrow-minded technologists. An individual's freedom is determined, to some extent, by his ability to access information"[9]

The 380Z continued right through until 1985, when it was finally replaced by the company's new Intel-based Nimbus range.

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 12 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.