Research Machines Advert - October 1980

From Personal Computer World

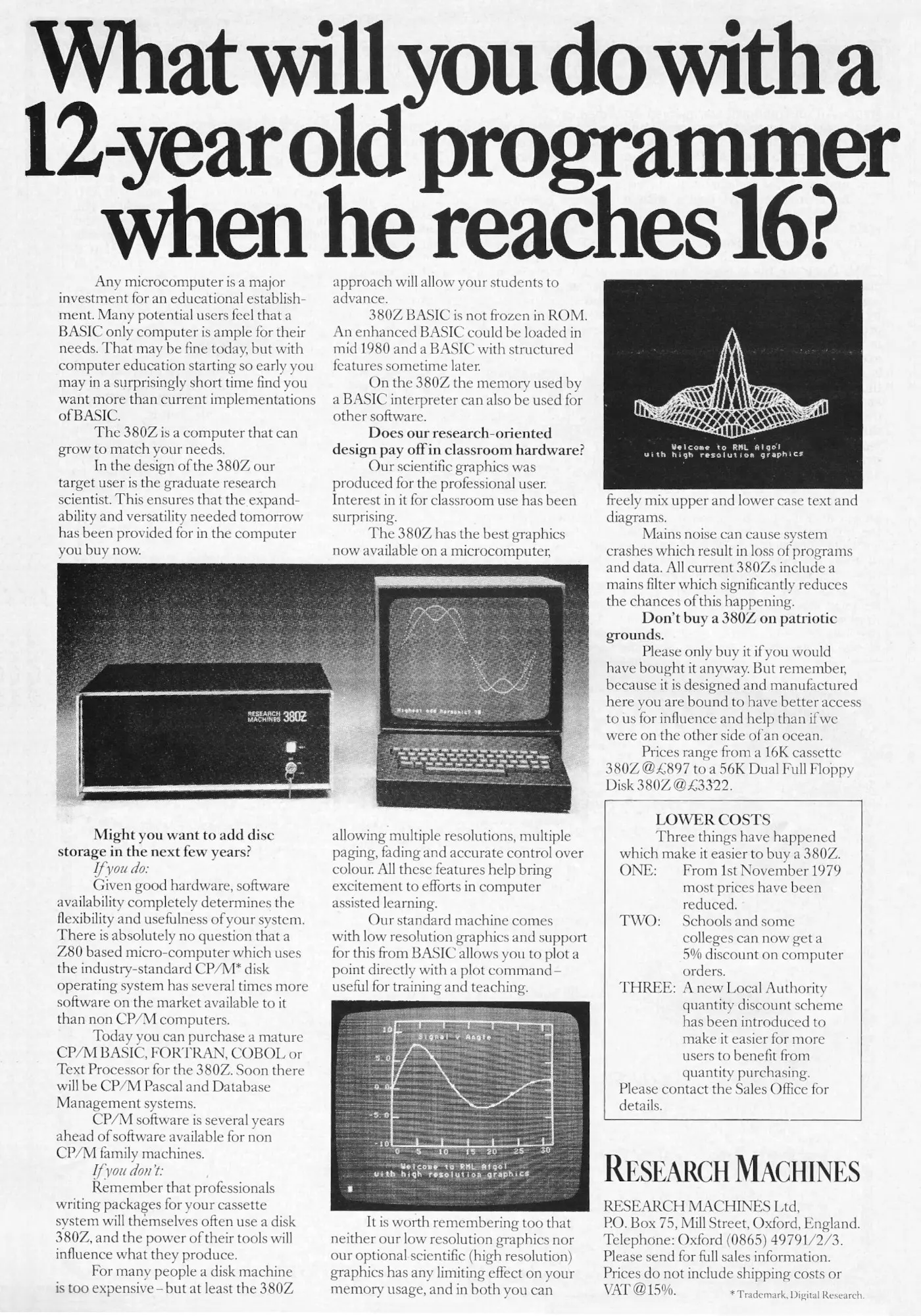

What will you do with 12-year-old programmers when he reaches 16?

This is an interesting advert - gender stereotyping aside - in the form of its implied message, from a company that controlled much of the UK Schools' IT hardware market until it finally bailed out of PC sales in June 2014[1].

It reflects the generation of kids who were the first to get access to computers in their own homes, like the ZX80, VIC-20 and so on, and had to learn how to program in BASIC in order to do anything useful.

BASIC wasn't always the most popular choice, with computer-scientist legend Professor Edsger Dijkstra - father of structured programming and famous for saying "GOTO statements considered harmful" - having a proper rant against BASIC, as well as hobbyist programmers in general, at an international conference in 1977.

Dijkstra grumbled bitterly that non-professionals and the BASIC language had put back programming by 25 years[2].

This seemed to be a position the advert seems to at least partly agree with, suggesting that when kids reach 16 they need something a bit more advanced than a box that runs BASIC to program on. Others have similarly suggested that no-one should program in BASIC after puberty[3].

And so to address this apparent market, RML was offering a Z80-based computer running CP/M, with alternative and "serious" programming languages Fortran and COBOL available.

It retailed for £897 for the entry-level system (about £5,870 in 2026 prices), which would frankly put it out of the reach of most home markets, but then it was primarily aimed at 6th-forms and colleges.

Fear of Technology: Visions of a Computer Future at the end of the 1970s

The end of the 1970s was marked by a widespread fear of new technology in popular media and society at large, a fear which perhaps really found its voice in the BBC's influential Horizon programme "Now the chips are down", which caused quite a stir[4] when it was first broadcast in March 1978[5].

Reflecting as it did upon a dystopian future where new technology would lead to widescale job losses, for instance with the use of robots in car manufacturing, the Horizon programme was even noted as one of the jolts that "woke up" an oblivious population by Prime Minister Jim Callaghan, although Callaghan had already initiated a study in to the impact of microcomputers a few months before back in the January of 1978[6].

The net result was that by the end of the year the Labour Government had decided to commit £55 million to promote the "revolution" in the UK, via its Microprocessor Applications Project[7], or MAP.

The feeling of unease was prevalent enough that many articles in the press would attempt to take away the fear of technology by offering soothing examples of why people might want a computer in their own home.

One such example, although it could be said to be preaching to the choir as it appeared in August 1978's Personal Computer World, was written by none other than Magnus Magnusson, most famous as the long-serving host of television's Mastermind.

I've started, so I'll finish

Magnusson started with a microcomputer-economics lesson: the world's first business computer - Joe Lyon's LEO 1, built in 1951 - cost £5,000,000 whilst a 1978 kit offered pretty much the same performance for £500 or less, demonstrating how prices had fallen by one or even two orders of magnitude in each decade.

There then followed questions like "why should you buy a computer?", statements like "there are still many people who are a little afraid of the computer" or predictions like "just as dad buys an electric train set for his son's first birthday, so dad will buy a computer for his children's educational advancement and his own fun".

This seems to show that even as early as 1978, when there were very few micros actually in schools, computers were already seen as a de-facto solution to education problems.

Magnusson continued his essay with some other very common memes of the time:

"a computer really comes in to its own by helping you to plan your household budgeting. Your computer can find the solutions by taking all your personal circumstances in to account. All you do is feed in your monthly pay cheque and your fixed expenses and let the computer take out the drudgery and come up with the answers".

There was also the perennial favourite "[a computer] can help you reduce your energy consumption by controlling the central heating and opening or closing curtains or windows" - a trope that by the 2010s had spawned smart thermostats, a perfect example of a solution looking for a problem.

Relief from drudgery was a recurring theme, but according to Mike Cooley, formerly of the AEWU and TASS unions, microcomputers and the rest were too often presented as liberating people from "all the boring, routine back-breaking tasks that they had been engaged in".

It was also a myth that this would somehow naturally lead people to be free to engage in creativity and have better, more satisfying and worthwhile jobs[8] - the problem with drudgery being that as soon as you removed it, some other boring job would come along to take its place.

The belief that sufficient programming was enough to model any behaviour, given enough data, also seemed to be widespread.

Professor Jay Forrester, part of the MIT team that devised the infamous, influential and later-discredited 1972 "Limits of Growth" study for the global think-tank Club of Rome, was quoted in an address to the US Congress as stating:

"The human mind is not adapted to interpreting how social systems behave... until recently there has been no way to estimate the behaviour of social systems except by contemplation and guesswork. The great uncertainty with mental models is the inability to anticipate consequences of interactions between parts of a system."

Forrester continued with the somewhat naïve:

"This uncertainty is totally eliminated in computer models. Given a stated set of assumptions, the computer traces the resulting consequences without doubt or error. Any concept or relationship that can be clearly stated in ordinary language can be translated into computer model language"[9][10].

Meanwhile Magnusson concluded his ernest and somewhat parochial article "Computing for Everybody" with a quote from the editor of Personal Computer World:

"The world is full of divisions: rich and poor, north and south, developed and under-developed, literate and illiterate. Soon, if we do not make great effort, there will be another division - between those of us who are aware of the uses and the power of the personal computer, and those who are not. It will be the difference between surviving the information tidal wave and being drowned by it"[11].

Social divide

Eric Lubbock, who was by now elevated to the status of Lord Avebury of the UK's upper parliamentary chamber, the House of Lords, echoed this sense of an upcoming divide when he gave a talk at the University of Sussex on 1st November 1979, stating:

"Here in the UK ... there does not seem to be any consciousness of a need to explain these advances to the consumer or the trade unionist, nor to encourage them to participate in the discussion, let alone the management of the changes that will so profoundly affect them. There is a danger that Britain may on the one hand become polarised in to a fairly small elite of professionals and managers who are keen to apply the available technology, and on the other, the mass of the people for whom the word micro-electronics conjurs up only images of Big Brother and the dole queue. The contrast between the two groups would be stark, because the range of skilled and semi-skilled activities in between would have virtually disappeared. This would be a prescription for extreme social unrest, perhaps disintigration."[12].

An archetypal dole queue, featured in the documentary New Technology: Whose Progress?", first broadcast in 1981. Source: https://archive.org/details/newtechnologywhoseprogressLord Avebury's talk was in response to the announcement of a Government programme intended to get the public engaged in a debate on informatics and society.

There was still a general lack of awareness amongst the public of the threats and/or opportunities of microcomputers, despite a nationwide campaign throughout 1979 "aimed at alerting the country's key decision makers to the facts of microelectronic life".

That campaign - part of the Government's £55 million Microprocessor Applications Project and launched with the co-operation of the National Computing Centre (NCC) - had involved over 50,000 people from the business world taking part in 140 workshops, as well as presentations to over 12,000 Union members at various conferences[13].

Jobs holocaust

Barrie Sherman waves a cigar around as he talks on Horizon. © BBC Horizon 1978The Trade Unions, which in 1980 represented 12 million workers[15], were not quiet on the matter of the perceived impending jobs crisis.

Clive Jenkins, general secretary for the white-collar Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs (ASTMS) union laying his cards on the table in the book "The Collapse of Work", co-authored with Union researcher Barrie Sherman.

Malcolm Peltu, reviewing the book in September 1979's Personal Computer World wrote that it:

"clearly forsees a future in which information technology creates an environment where there is substantially smaller demand for both physical and white-collar clerical labour, leading to the possible creation of a 'leisure society' in which it will be normal for most people to be 'unemployed' most of the time"[16].

Despite Jenkins and Sherman calling this a "jobs holocaust", Peltu also mentioned his surprise that they (and most Unions) were pro technology, with Jenkins and Sherman going on to say that we must "first ensure that we do get our technological revolution and we get it early enough".

Sherman had also appeared on a panel discussion following the first broadcast of the Horizon documentary saying that "there are economic, political and social repercussions" of the move to a micro-processor-dominated society[17], a sentiment echoed elsewhere on the left of the political spectrum by former Labour Cabinet Minister Mervyn Rees who, whilst opening a new Computer Workshop in Leeds, suggested that "a new social class will grow up in response to the micro, in the next decade"[18].

The ASTMS union was one of the first organisations in the UK to take the threat to jobs seriously, saying that "the days when fears of unemployment caused by computing could be discounted have definitely vanished".

The union was forecasting 3.8 million unemployed by 1985 and 5.2 million by 1991 (the actual figures were 3.0 million in 1985 and about 2.4 million in 1991[19]).

Several studies in 1978, including one undertaken for the BBC and another by the Cambridge Economic Policy Group and published in The Times in May of that year, increased the feeling of pessimism by foreseeing constantly increasing unemployment fuelled not just by the microprocessor but also by an increase in population - another popular fear at the time.

Jenkins and Sherman said of this "if at present we cannot provide jobs for 1.5 million people, how will we cope with an extra 2.5 million?"[20].

Various government attempts to put off this expected rise in unemployment, like increases in short-time working and job-swap schemes, as well as encouraging young people to stay in education for as long as possible were seen as futile attempts about as useful as "trying to shovel the tide back".

Mostly though it was a message of increasing unemployment: Dutch electronics company Philips was expecting to reduce its 500,000 workforce by over half in ten years, as by that time it was forecasting that improvements in production methods through technology would leave it 56% overmanned.

Elsewhere 128,000 jobs were forecast to be lost in the US car industry by 1985 and a proposal for an unmanned factory in Japan suggested that a control crew of ten could do the work of 700.

Even as late as 1982, Chairman of Mensa, inventor and computer pioneer Clive Sinclair was also forecasting wide-scale unemployment, when at the third annual Mensa symposium in Cambridge he predicted 10 million unemployed in Britain by the end of the century, with only 10% of the population remaining in manufacturing.

Sinclair actually saw this as a benefit, suggesting that "positions in industry are inimicable to the human spirit" and that "a move away from this present type of organisation will restore the potential of the individual".

He went on to suggest that this would lead to an affirmation of class distinctions and would lead to a revival of "traditional and artistic patronage" before concluding:

"early in the next century we will have made intelligent machines, ending for all time the current pattern of drudgery. It may well be that western civilisation is just about to flower"[21].

One of the problems with a sudden unleashing of "leisure" was who would pay for it, as the traditional way of distributing wealth had been via the pay packet.

However in the new world order, wealth would be concentrated in the hands of the elite who had control of the computer systems and other various tools of "high technology", whereas for the masses without a job there would actually be no money to pay for their new-found life of leisure.

All that would be left in this new World Order would be a new drudgery of looking for things to do, with millions of people living a life of enforced idleness. Unless, that was, a way could be found to share the wealth - which given human nature might seem unlikely.

MP Tony Benn, speaking in the documentary film "New Technology: Whose Progress?", first broadcast in 1981, suggested that a society where millions of disenfranchised people had been pushed outside of the the democratic process would lead to:

"a technocratic domination of society, which is one of the real dangers that science - which began as the liberator of man - could end up enslaving man by putting its power at the disposal of those who already own our factories, or own our newspapers or our television stations, and in this way impose a tyranny in the guise of liberation"[22].

This prediction feels eerily post-modern, as tech companies like Alphabet/Google/YouTube, and more traditional media companies like Disney, buy up and control more and more of the media and information the world consumes, whilst a handful of Social Media companies influence and undermine discourse and politics at a national level and beyond.

Editor of the magazine 'Computing', Richard Sharpe, saw this emerging in 1981 as a battle for data between technology companies, where perhaps one or two would win out and have "control over what in the future will be a major means of handling information", before forecasting that:

"we'll be in a position where a primary life source is controlled by one corporation with enormous profits [staffed by] very few people, and it is able to call the tune for what future developments are".

Sharpe couldn't have begun to imagine Facebook and how its platform can pervert even the most basic democratic processes, but he could see what was coming.

Disemployment and de-humanisation

The process of redundancies had already been seen to happen.

Hitachi employed 9,000 people on colour TV manufacturing in 1972 but by 1976 this was down to 4,300, with Panasonic and Sony reporting similar losses.

Overall, employment in the Japanese TV industry had gone from 48,000 to 25,000 whilst in the same period production had risen 25%, from 8.4 million to 10.5 million TVs a year.

Jenkins and Sherman called this the process of "disemployment", but the real fear came not so much from the change itself, but from the speed in which it was happening.

Previous revolutions - both agricultural and industrial - had occurred over several generations, giving at least some time to adapt, but the computer revolution seemed to be happening in the space of only 20 years, with a possible outcome, forecast without a trace of hyperbole, "worse than World War Three"[23].

There was also a fear that this time around the revolution would lead to de-humanising and de-skilling of not only the manufacturing workforce, which had been affected by the "first wave of automation", but also the white collar sector, where the unfamiliar shadow of Taylorism loomed large.

In the previous industrial revolution, movements like the Luddites were not railing against the machines as such, but were reacting to the loss of highly-skilled craft jobs, the sort where knowledge had been passed down through generations.

It seemed that nothing had been learned from this history, and the same thing was about to happen to clerical, intellectual and office work.

There might not have been the same sense of mourning for the loss of generations of typewriter skills, but there was still the worry that "knowledge" jobs would be replaced by machines or technology that absolutely anyone could use - typists replaced by word-processors, accountants by spreadsheets and so on.

F. W. Taylor's famous studies of the Bethlehem Steel Works, amongst others, led to "The Principles of Scientific Management" which was published in 1911.

This fundamentally saw work as something that could be analysed using time and motion studies so that "what constitutes a fair day's work will be a question for scientific investigation, instead of a subject to be bargained and haggled over"[24].

From this collected data, the most efficient and cost-effective methods could then be determined by the management, generally without any participation from the workforce under investigation.

White collar work, like clerical, accountancy and so on, had not been particularly suited to time and motion analysis, but some feared that the introduction of word processing, computerised telephone systems and electronic messaging could all be used to monitor the productivity of office workers for the first time.

At the start of the 1980s, about one quarter of the US workforce worked in offices, at a cost of $300 billion, and whilst productivity in manufacturing during the previous decade had risen 90%, it had only risen 4% in the office, which was still a very labour-intensive environment.

The lack of office productivity improvement was in part due to businesses having invested some twelve times as much in factory automation as they had in office technology over the previous decade, but this was changing rapidly and it was specifically where the next wave of computerisation was being targeted, with increased "management control" being offered as a particular benefit of the new technology.

Franco di Benedetti, the joint managing director of Olivetti, suggested that the role of computers in the office was as "a technology of coordination and control of the labour force", whilst he also believed that "a factor of fundamental importance in mechanising structured work is the capacity for control which the manager thus acquires".

IBM's William F. Laughlin went further to state "People will adapt nicely to office systems - if their arms are broken - and we're in the twisting stage now"[25].

There was even a fear that the office could end up working shifts, as management sought to squeeze out as much return as they could from their expensive investment in IT, 24 hours a day.

The irony of becoming slaves to the machine that we had created was not lost, as Mike Cooley said:

"Technology was made by human beings, and if it's not doing for us what we want, then we have a right and a responsibility to change it. It's not given, like the sun or the moon or the stars - it was designed by people, and we could design it differently".

The very quality of working life itself under this sort of technocratic regime came into question, with Professor Geert Hofstede of the European Institute of Advanced Studies in Management Techniques suggesting that in order to prevent the resurgence of Taylorism in work and promote more of a work-humanisation philosophy:

"management must be willing, or forced by circumstances, to let some control be taken away from it".

Geert saw managers and employers as a "ruling elite" and characterised those promoting a quality of working life over alienating scientific approaches as a "revolutionary elite" whose ideas might even trigger "a third industrial revolution".

The extreme left also had some ideas on how to keep humans in work: in a book published by the Socialist Worker Party and entitled "Is a Machine After Your Job?", author Chris Harman suggested that:

"Workers of one sort or another have the power to impede the introduction of new technology. The employing class cannot work it without us".

As Malcolm Peltu summed up in a review of this work in July 1980's Personal Computer World:

"it's clear that new technology will be used as a weapon in many industrial relations battles - and Harman provides a crude insight into the fears and reactions that may predominate"[26].

The Union view was perhaps not without merit, at least if a comment by Lord Spens, speaking in the House of Lords in May 1979 was anything to go by:

"Silicon chips do not belong to the Unions; they do not go on strike; they do not ask for more and more pay; they do not need holidays nor heated offices; nor tea breaks; they are very reliable and they do not make mistakes; they need very little space in which to function; they are very cheap; they use very little energy; and they are here now - waiting to be brought into use"[27].

Another major fear of the unions was that the world of work was entering a new phase where management was attempting to squeeze out and control labour to a much greater degree, or simply to replace "human intelligence and human energy" with machines, which would reduce the pay spent on workers and thus render industry more efficient.

According to Harley Shaiken of the United Auto Workers union in the US, the goal of "productivity" had become an all-out ideological war between management and workers.

Meanwhile, companies like Cincinatti Millicron were advertising their robots as never tiring, never complaining and being able to work three shifts a day at a cost-per-hour significantly less than meat sacks.

Job cuts, or not?

Trade Union members weren't the only ones publishing books on the forthcoming job apocalypse.

Adam Osborne of Osborne Computers and author of several well-respected books on software and technology published his own book on the matter at the end of 1979.

Entitled "Running Wild", the book offered some similar predictions, suggesting that 50% of all jobs would be lost in the next 25 years and that around 50 million jobs would be lost in the US alone. He continued with the warning

"No-one is paying attention to the way in which computers and microelectronics are being used, or on the impact such uses might have on our society. We had better start paying attention or we will be very, very sorry".

Whilst studies like Jenkins and Sherman's were suggesting that:

"the most revolutionary impact of technology is likely to be in office and white-collar jobs [which had been] under-automated, labour-intensive activities which had soaked up unemployment created by the switch away from agriculture and manufacturing"

Osborne was contradicting them (and himself) when he suggested:

"when push comes to shove, microelectronics and automation will not have a dramatic impact on office jobs. Fewer secretaries will be needed, but they are in short supply anyway. Office jobs will be more demanding ... but there will be no significant decline in the number of jobs".

Malcolm Peltu of Personal Computer World concluded that Osborne's book was "a turgid mish-mash of superficial, badly-organised and often misleading punditry", although in reviewing one particular chapter on where computers should be excluded, Peltu offered his own remarkably prescient observation on real computer abuses which are still relevant 35 years later:

"computers in defence systems that nearly caused World War III, the invasion of privacy by unwarranted access to medical files or the use of computers by dictatorships to infringe human rights"[28].

One problem with a lot of this future-gazing was that it was based upon an assumption that technology would always have a mostly negative impact upon society. There were a lot of imperative-but-fatalist predictions from the likes of the NCC including:

"Britain has no option but to accept the microelectronics revolution; it must be adopted to improve productivity and competitiveness; electronics must be introduced into education so that the next generation may be aware of its capabilities; it will de-skill some jobs yet enhance others; Japan and the US are five years ahead".

There were various other "dire consequences" bandied around about the loss of competitiveness if the UK didn't join the race for computerisation.

The UK's Conservative Party saw the semiconductor revolution as a direct way out of the "multiple crises [the country] faces" whilst the NCC's report even went as far as to suggest that microelectronics would challenge attitudes at the heart of what it meant to be employed, when being employed was broadly seen as fundamentaly important to humanity's very existence in a society where people identify as their employment before anything else: teacher, builder, carpenter, plumber.

As Mike Cooley of the AUEW said on the influential "chips" documentary, "people relate to society through their work".

This was a position that Jenkins and Sherman also took when they stated that not only would the working week "inevitably shorten" but that:

"it is impossible to over-dramatise the forthcoming crisis as it potentially strikes a blow at the very core of industrialised societies: the work ethic"[29].

Technological determinism

Sociologist Frank Webster disagreed with much of this viewpoint, saying that:

"to talk in a way which assumes that technology is here today and hence social implications will follow tomorrow is a facile cariacature of the complexity of social organisation and social change. The sociologist would resist the current assumption that technology arrives from out of the blue to deliver a number of consequent social effects".

He went on to make the point with the example of television, which was not a technology simply invented in isolation for later massive social effect, but that it "simply responded to, and was shaped by, social trends in society".

TV had neatly adapted to fit the growing trend of a more isolated, smaller, family unit, in other words it was "consolidating our latter-day family structures"[30].

Or, to put it another way, television, despite being a significant technological invention, did not cause the break up of the extended family any more than computers would cause society to end up working a two-day week.

Webster concluded that "the spectre of technological determinism must be removed... the idea that technology is in some way aloof from society". This point was also made by Daniel Bell of Harvard University who stated that:

"a change in the techno-economic order does not determine changes in the political and cultural realms of society but poses questions to which society must respond"[31].

Bell referenced Canadian economic historian Harold Innis, who was firmly in the "technological determinism" camp but who saw changes in communication technology as the significant disruptive factor.

Innis argued that each distinct stage of Western civilisation had been dominated by a particular mode of communication - cuneiform, papyrus, pen, paper, printing press - and that "the rise of a new mode was invariably followed by cultural disturbances"[32].

Radio, television and now the internet could be added to that list, but the way the latter "mode" has changed global communications is perhaps the most significant, greatest and potentially dangerous of all.

Jenkins and Sherman had also been in the determinism camp, a position which came from an analysis of the industrial revolution where huge and fundamental changes had been wrought on society:

"Technological change has not advanced with a calm inevitability and a minimumn of social disharmony. On the contrary it has brought about not only social and physical misery [but] long-term and large-scale unemployment"[33].

Television also cropped up as an example of how optimism, which often seemed to come with a belief that robot servants were the answer to the world's problems, might be mis-placed.

In an essay published in the book "The Computer Age: A Twenty Year View", Joseph Weizenbaum argued that "the euphoric dream of micro enthusiasts" was like that of the belief that radio, satellite and TV technology would only offer the beneficial influence of teaching the correctly-spoken word, providing the best drama and offering the most excellent teachers.

In fact Weizenbaum suggested that television generally revelled in its output of "everything that is the most banal and insipid or pathological of our civilisation" with only the "occasional gem buried in immense avalanches" of rubbish.

Trust the machine

Weizenbaum feared that computers were not likely to be employed "for the benefit of humanity" and cited an incident in the Vietnam War where an Air Force computer had coordinates for a bombing raid in to Cambodia altered so that it would look like the raid was on "legitimate targets" in Vietnam.

The false data was simply accepted as "truth" by the Pentagon computer to which it was transmitted, but it was this absolute trust in the computer which was a fundamental problem that was also highlighted in a 1978 letter to Personal Computer World from Intel's Bill Ringer, which stated:

"There is a danger to our personal freedom. There will come a day when almost every aspect of our lives is affected by a computer of some kind. We will allow this to happen because it will be very efficient. We will be conditioned to trust our computers, and therein lies the danger. We will require an efficient method of interrogating the very principles and assumptions behind the logic of any program at every level"[34].

This issue remains a problem, with an increasing uneasiness about how little transparency there is surrounding the "black box" algorithms of companies like Google and Facebook/Meta that filter what we see and influence much of our on-line lives[35].

It can also be seen in the rise of AI-generated news, and deep-fake images and video.

Weizenbaum went as far as to suggest that the developer whose code falisfied bombing reports was "just following orders" in the same way as Adolf Eichmann, the SS officer largely responsible for organising the Holocaust. He suggested:

"The frequently-used arguments about the neutrality of computers and the inability of programs to exploit or correct social deficiencies are an attempt to absolve programs from responsibility for the harm they cause, just as bullets are not responsible for the people they kill. [But] that does not absolve the technologist who puts such tools at the disposal of a morally deficient society".

A paper-tape copy of Weizenbaum's Eliza program for an Altair 8800, at the Centre for Computing History, Cambridge This particular and emotive view of the application of technology overlooked the often unintended consequences of scientific discovery, even when its initial intent was to assist war.

Michael T. Dertouzos, in reply to Weizenbaum's essay, took issue with this "Weizenbaum doctrine" by offering an example: "The safety of today's worldwide air transportation system rests on [the] earlier development [of radar during World War II]"[36].

There were also examples of industries where computers provided efficiencies or safety-management that was barely feasible with solely human input, like nuclear power, although even that had its limits.

In the famous Three Mile Island partial-meltdown incident, the computers monitoring the crisis were "several hours behind reality", on account of the difficulties of processing the millions of extra units of information arriving each minute, rendering their output all but useless, apart from later as diagnostics.

Weizenbaum had concluded his original essay with some open-ended questions:

"What limits ought people in general and technologists in particular impose on the application of computers? What irresistable forces are our worship of high technology bringing in to play? [and] what is the impact on the self-image of humans and on human dignity?"[37].

Weizenbaum was known to have a fairly ambivalent view of computer technology and would later become a leading critic of artificial intelligence.

Back in 1966 he had produced a program called Eliza, which used natural language processing and pattern matching to give the appearance of being able to hold a conversation, with a style that was like "a brilliant parody of a psychotherapist".

Weizenbaum became increasingly concerned that people were taking Eliza too seriously, with journals predicting "the total computerisation of the psychiatric industry" and with his own secretary one day asking that Weizenbaum leave the room so she could consult the computer in private.

In his 1976 book "Computer power and human reason", Weizenbaum concluded that computers can do almost anything - except the things that are actually important.

His main point was that there was a major difference between computing power and real intelligence, that the human quality came from physical, moral and emotional experiences that machines can never know - "machine intelligence will never be more than a pale copy of limited aspects of human thought", as George Simmers, writing in Popular Computing Weekly summed it up[38].

Turning Japanese

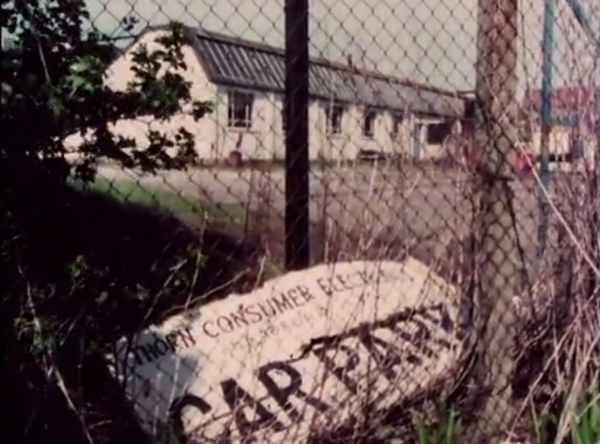

Thorn Electronics' abandoned factory, in Bradford, Yorkshire © Education Media Film, from the documentary "New Technology: Whose Progress?" 1981It was not just the threat from computers themselves that gnawed away at the collective psyche, but more directly the danger posed by foreign competition.

The UK was still smarting from the destruction of its motorcycle, ship-building, camera and television-manufacturing industries at the hands of cheaper and better Japanese imports.

It was like how the Swiss watch industry had been decimated by the arrival of cheap digital watches, and the adding-machine industry had been wiped out almost overnight by the arrival of the electronic calculator.

Some companies, like Thorn Electrical Industries, decided to "become Japanese" by adopting Japanese methods, which mostly meant maintaining the same output whilst shedding 50% of staff[39].

Only a couple of years later, Jack Tramiel of Commodore said that his company must also "become Japanese" as a way to fend off the much-feared onslaught of computers into the US market from the Far East.

The television-set industry was highlighted as being particularly interesting by Jenkins and Sherman as it revealed an endemic problem in the UK - the ability to consistently under-estimate the impact of new technology and the speed at which these new technologies would be adopted.

In 1965, both the BBC and ITV had been asked to estimate how many new colour TV sets would be required in the next ten years.

Andy Grove, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore of IntelThe BBC guessed at 750,000 whilst ITV, worried that it was madly over-estimating, came in with 2 million. The actual figure was 8 million[40].

Because of the recent bitter experience of having lost entire industries to international competition, it was seen as crucially important to try and keep a hand in the new wave of microelectronics.

Quoting Robert Noyce, the inventor of the first monolithic integrated circuit, in an essay written in 1979 and published in January 1980's Computer Age, MP David Mitchell wrote

"It is in the exponential proliferation of products and services dependent upon microelectronics that the real microelectronics revolution will be manifested. If we are to increase our competetiveness in world markets or to hold our own in our own markets, we shall have to learn how to exploit every benefit of the new technology in developing our industry and commerce - and we shall have to do it more quickly and to better effect than our overseas competitors".

Referring back to the Government's on-the-road awareness project, Mitchell concluded that:

"MAP has made an encouraging start, but there is still a long road ahead. In the end, it is only industry - and of course I mean both sides of industry - who can close the technology gap at present existing between us and our competitors and which underlies the diminishing wealth available to our people"[41].

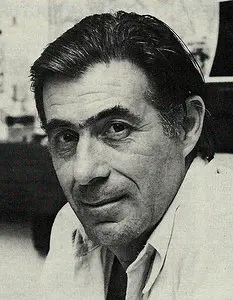

Christopher Evans, the time capsule, and Medical Mickie

Dr. Christopher Evans, © Personal Computer World, January 1980Shortly before all of this doom, in 1978, a time capsule containing various mementos of Britain at the time had been sealed and put on display at the London Planetarium by noted computer scientist and visionary Dr. Christopher Evans, author of the influential "The Mighty Micro".

The influential book, published in 1979, led to an ITV TV series of the same name and was said to have inspired the BBC's Computer Literacy programme, although planning for that had already started.

In it, Evans offered several predictions for the future, which were summarised in the book's jacket blurb as:

"A twenty-hour working week and retirement at fifty… A front door that opens only for you and a car that anticipates danger on the roads… a “wristwatch” which monitors your heart and blood pressure… an entire library stored in the space occupied by just one of today’s books… science fiction? No, for by the year 2000 Dr. Christopher Evans predicts, all this will be part of our everyday lives[42]".

Apart from retirement age and the working week, many of these are now a reality: collision avoidance and driving assistance in cars, video doorbells, fitness watches and Wikipedia. English Wikipedia's compressed text size as of 2024 was around 24GB[43], which would comfortably fit on even the smallest hard drive or tiny memory card.

Meanwhile, the time capsule was due to be opened in the year 2000, although no trace of it now appears to exist[44], but it was noted that it contained much about the "general gloomy depression about the future" prevalent at the time.

Christopher Evans, on the other hand, was concerned enough to send a message to the 21st Century looking forward with enthusiasm to the expanding horizons of the coming micro generations"[45].

Evans started off as a psychologist before becoming a computer scientist when he moved to the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington in around 1974.

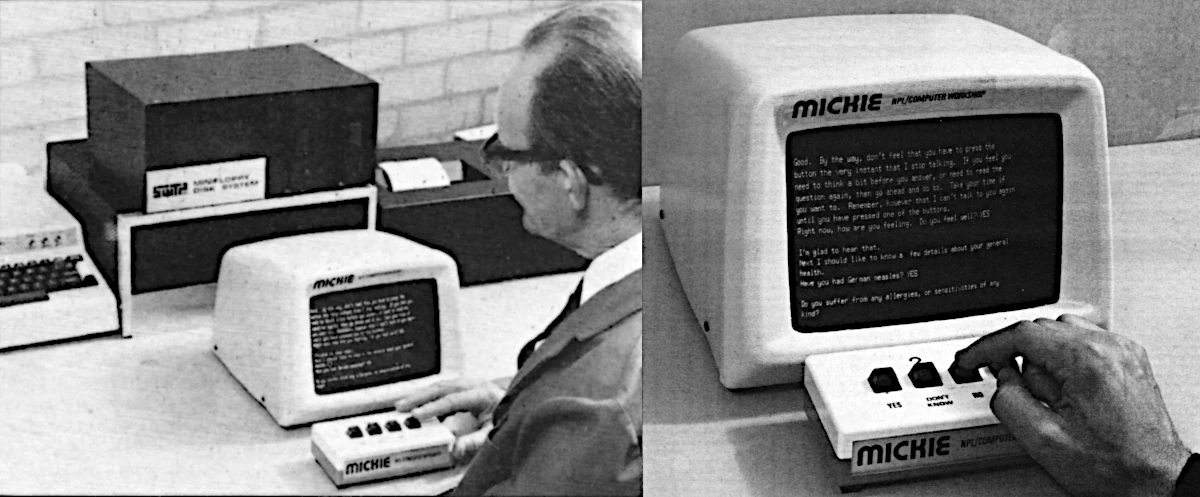

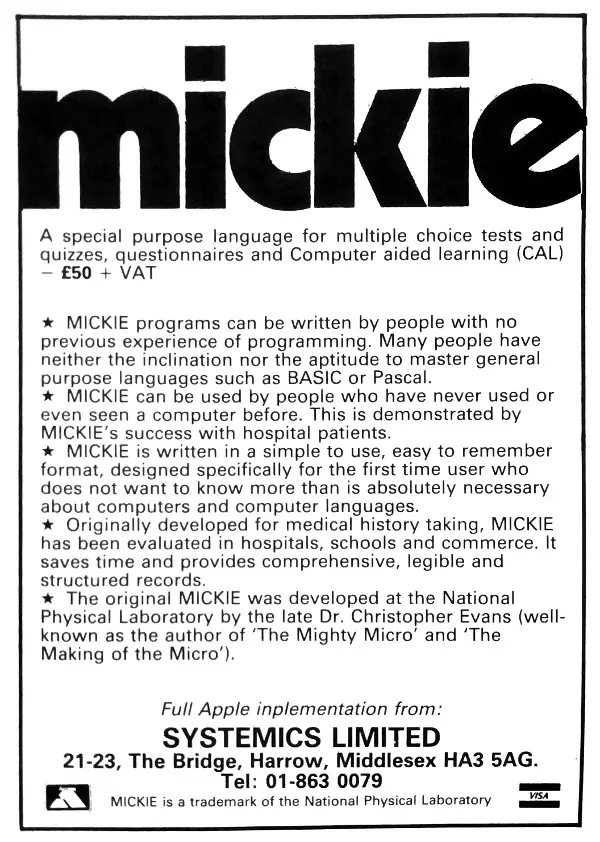

Whilst at the NPL he became famous for writing a medical interview program called "Mickie" (after Medical Interviewing Computer), which NPL went on to release, after Evans' early death at the age of 48, for the Apple II in 1982[46].

Mickie had started out in the early 1970s as a project running on a Honeywell time-sharing mainframe, actually hosted in Cleveland in the US and accessed via dial-up.

As computer power improved and reduced in size, it was moved onto a DEC PDP-11/10 running at the NPL with the BASIC program transferring between the two machines with relatively few changes.

By the 1978, it was running on SWTPC's 6800 machine with 20K of memory and two 5¼" floppy disk drives, with the whole lot - including a VDU, printer and the yes/no buttons - coming from Computer Workshop for only £2,700 - about £21,700 in 2026.

Mickie, connected to a SWTPC 6800 micro, undergoes testing at the NPL. From Personal Computer World, December 1978

At the end of 1979, in an in-depth interview published posthumously in Computer Age in January 1980, Evans continued to expand upon his ideas for the future, suggesting:

"What I think is going to happen is that with the computer revolution, which will have a tremendous effect in increasing prosperity and removing drudgery, these so-called intellectual differences between people will be ironed out. I think the course of human development is largely dictated by technological developments, by market forces, and that human beings have very little option but to go along with them. And this means that though we instigate the computer, the course of the future is really out of our hands, because we cannot have a world without computers, in the same way as we could not any longer have a world without machines. Like it or not, the technology is going to overwhelm us. So, as for some of the eerie futures that seem possible, I don't think we've got much option. Take the case of machine intelligence. It's going to be just too useful for us not to develop it"[47].

This point of view was not too dissimilar to that of another well-known futurologist - Alvin Toffler - who had become famous for his sequence of "Future Shock" books.

Advert for the Apple version of Mickie from 1982. By then it had become a general-purpose framework for building questionnaires and Computer-Aided Learning © Practical Computing September 1982Published in 1980, Toffler's "Third Wave" - which was said to encompass molecular biology, space science and oceanics - also included information technology and microcomputers, which Toffler suggested were "among the most amazing and unsettling of all human achievements". He concluded that:

"[computers] enhance our mind-power as Second Wave technology enhanced our muscle power, and we do not know where our minds will ultimately lead us".

In a review of the book, Personal Computer World's Malcolm Peltu summed up Toffler as a "wide-eyed technology enthusiast"[48].

Evans' sense of being overwhelmed by machine intelligence, or AI, cropped up in the news again at the end of 2014 when pre-eminent scientist Stephen Hawking - once Ray Anderson of Torch Computer's Physics teacher - was interviewed about the upgrade to his communication system by Intel and UK company SwiftKey. He warned that:

"The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race. It could take off on its own and re-design itself at an ever-increasing rate. Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution couldn't compete and would be superseded"[49]

The Leisure Society: next time, maybe

So what happened in the end? Philips, the company that feared a halving of its workforce was probably right to do so. By 2011, it was down to 120,000 employees[50].

Employment in the US car industry was already in free-fall at the end of the 1970s - thanks largely to a recession - going from over 1 million to 630,000 by the end of 1982, so a 128,000 loss was a significant underestimate.

However, employment recovered and remained at around 900,000 for the rest of the decade[51].

There was however no collapse of society in to a rareified strata of über-nerds lording over a great mass of unemployed plebs, just as there was no leisure society and definitely no two-day week.

Computers just became a tool and, if anything, opened up a whole new industry of software, services and media, an impact much like Gutenberg's printing press had had in the 15th Century, where the jobs of woodcutters and illustrators were destroyed overnight but new jobs in print and news replaced them, even if they were not always filled with the people now out of work.

In 1981, 23% of the working population was in manufacturing, but by 2011 this was down to only 9%, thanks partly to the increase in automation using robots and computer control that had been going on since the 1960s, whilst 81% of employment was now in services[52].

Give or take the odd recession, unemployment hasn't increased much overall despite a significant increase in population - some other drudgery will always be found to fill the void left by the removal of another, like how data entry replaced typing pools.

The UK, did however lose much of its ground in software, an industry where at the end of the 1970s it was considered a world leader and where it could still export software trading systems to American banks or develop revolutionary systems like the EMI body scanner, which EMI sold £200 million-worth of in a couple of years.

Computers largely failed to change household management, as throughout the PC era they would normally be found in a box room or a study, and so were far too "off line" to be that influential over daily life.

Instead, they became mostly a tool for the consumption of music and video - their runaway success, ubiquity and cheapness as mobile phones and tablets has meant that they are now mostly just throw-away consumer electronics.

The idea that computers can control heating - a technology Holy Grail which the great Magnus Magnusson was forecasting even in 1978 - is broadly true, with smart electronic thermostats and programmers, but Google's 2014 purchase of thermostat company Nest was less about central heating and far more about technology to enable the next great fad - the Internet of Things[53].

The start of the 1980s marked a real transition.

Even by the end of the first year of the new decade, the fears of the previous few years already seemed quaint, and Malcolm Peltu was quick to point out that in hindsight no-one actually seemed particularly sure about what the revolution was exactly: was it microelectronics, information, the second or third industrial, communications or telecomms? Whatever it was, the revolution had happened.

Fear of computers would - at least until the second coming of Machine Learning and "AI" in the late 2010s and beyond - give way to optimism and acceptance as micros were about to make the jump from expensive tools of the controlling elite to mass-market items, thanks to two things.

One was price: Commodore and Sinclair would transform the market by offering computers that far more people could afford.

The other was more subtle: the new wave of small computers about to be unleashed and aimed at the home were seen to be a lot friendlier and non-threatening because they connected directly to and were thus part of the thing that was already at the very heart of the modern home's social life: the television.

The real computer revolution was about to begin.

-------

The National Computing Centre produced figures from a survey of 1980 school leavers who had been trained as programmers, in an attempt to establish whether the "truths" widely held at the time that programmers must be either good at maths, bridge, chess or crosswords, had any merit.

Apparently not, as it was revealed that the best indicator of a potential programmer was "good grasp of English", followed by "general thinking ability" (think IQ tests).

Maths actually turned out to be no guide whatsoever.

Guy Kewney, writing about this revelation in Personal Computer World suggested that "the average Data Processing manager [likely to be the one employing these school-leavers] remains convinced that home micros are a dream because ordinary people will never be able to program them".

The NCC noted drily that "Data Processing managers are exhibiting 'resistance to change'"[54].

Date created: 21 February 2020

Last updated: 28 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.