Sinclair Advert - June 1984

From Your Computer

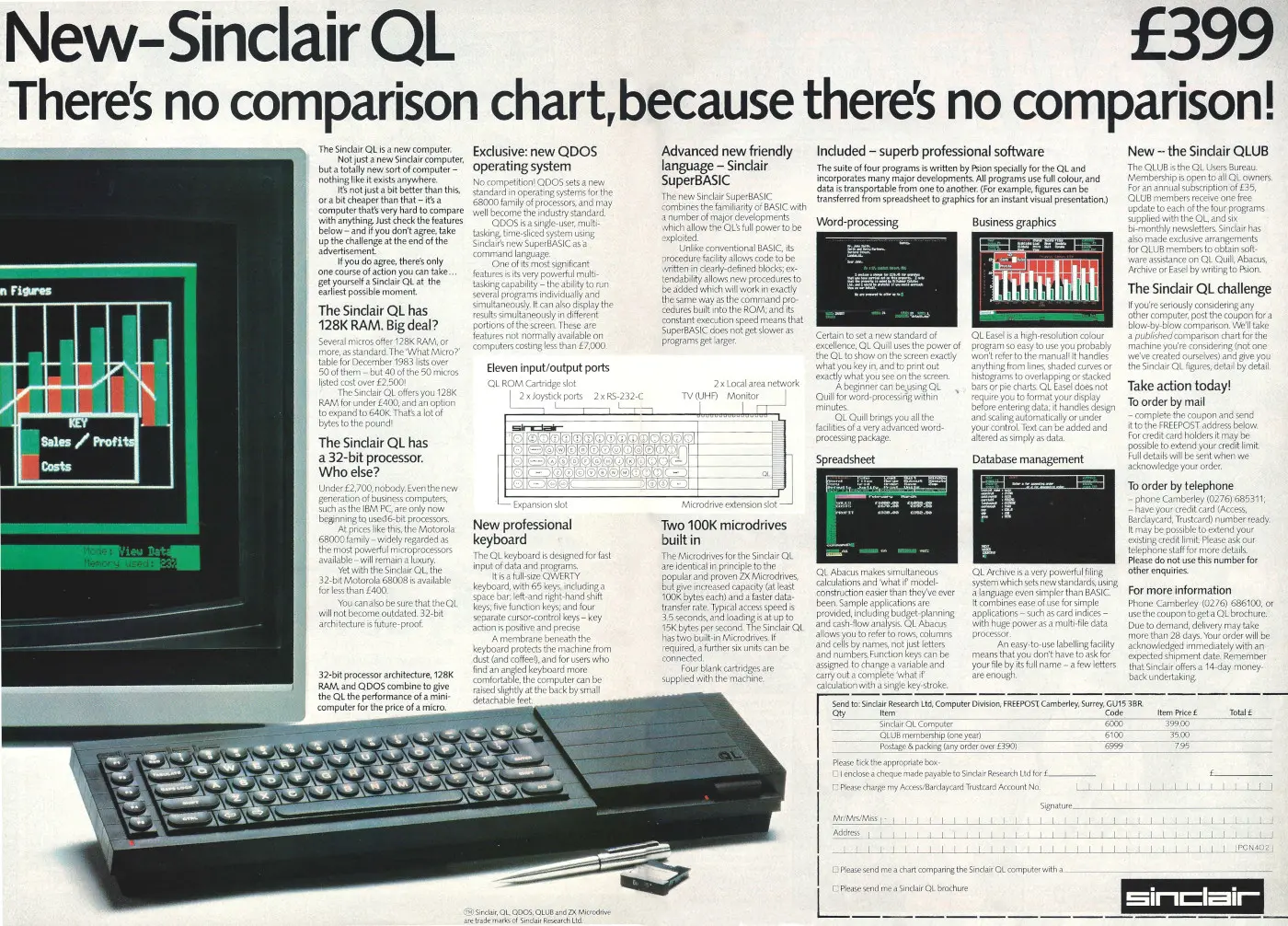

The New Sinclair QL - There's no comparison chart because there's no comparison!

The Sinclar QL, or "Quantum Leap", also known internally to Sinclair Research as the ZX83[1], was Sinclair's first and only computer based upon the Motorola 68008. The 68008 was a version of the 68000 processor with the same 32-bit architecture internally but with 16-bit addressing and only an 8-bit memory bus.

The 68008 was also physically smaller than the 68000, occupying a third of the space of its bigger sibling, and it had only 48 pins compared to the 68000's 68, all of which made it easier to build cheaper systems around[2].

However, the 8-bit memory bus also made it only half as fast as its big brother at accessing memory[3].

Towards the end of the development cycle Motorola - which had recently invested £65 million at its East Kilbride fabrication plant where it was hoping to produce 68008 chips for the QL - dropped the price of the "real" 68000 as it was now able to manufacturer it in plastic packaging, rather than the original ceramic, but Sinclair decided to stick to the original plan as the QL was already running late.

All of this meant that the advert's claim implying that the QL is a full 32-bit computer is therefore a little optimistic - if nothing else, the QL's BASIC interpreter was actually slower than the BBC Micro, a computer based on the 1975-designed 6502 and which was launched in 1981[4].

The original processor for the ZX83/QL was expected to have been the same Z80 as used in all the previous ZX micros. It was however changed to the 68008 late in 1982, apparently more for marketing reasons than for any particular benefits it offered. In a wide-ranging article published in January 1986's Your Computer, authors Ian Adamson, Richard Kennedy and Freda Trovato concluded:

"Apart from its capability to perform 32-bit arithmetic directly, this poor relation of the 68000 family has little going for it in computing terms. The restriction of the eight-bit address bus slows the whole thing down, and a Z80 could run faster. When Sinclair chose a new hip chip, more to create the capacity to claim innovation and a "32-bit chip" in the ads than to improve their machine, the price differential was a lot more - 68000s being five times the price of 68008s. Never one to spend a penny more on components than he has to, Clive took the 68008, despite being told by Motorola that the price [of the 68000] would drop. Effectively, this decision has lumbered the QL with an illusory advanced chip which renders it uncompetitive with Macinstosh 520STs and the like. Even if Digital Research can port the GEM system across to the QL, who's going to want it if it runs at half its original speed?[5]".

It wasn't just the change of processor that made it incompatible with all previous Sinclair micros, including the ZX Spectrum.

The machine's new BASIC - known as SuperBasic - could address 90K of RAM and for the first time included structured programming commands such as as procedures - something that had been available on Acorn's BBC Basic since the end of 1981.

The QL also had some multi-tasking ability thanks to its new "almost flawless" QDOS operating system[6], written by Tony Tebby.

Nigel Searle, Sinclair's managing director, © Popular Computing Weekly, 15th September 1983In order to encourage software houses to write software for what was at the time still referred to as the ZX83 or "professional computer", Sinclair announced a "low cost development system" in November 1983, with MD Nigel Searle suggesting that:

"It is our intention that there should be, for our next computer, a relatively low-cost development system available - priced at around £1,000 (£4,410 in 2025). Keeping the serious but small software house working on Sinclair products is very important to us".

Searle went on to suggest that a VAX development system was clearly outside the budget of a small software house and that developing software on the machine itself was "no fun" (notwithstanding that it was nearly six months out anyway), so Sinclair had put out a contract to develop such a system for "a reasonable sum of money".

However, the announcement also fuelled rumours that the new machine was no longer to be powered by the venerable Z80 processor that all previous Sinclair machines had used. Searle suggested that "[Sinclair] would use a processor other than the Z80 when we can get a good price. A 16-bit device might cost as much as £10".

The company had been known to be looking at National Semiconductor's 16032 CPU (later renamed 32016 as the former name sounded like a 16-bit chip), but didn't want to be stung by "choosing a processor which does not become a standard and is not supported by the industry", according to Searle[7].

The 16032/32016 did get chosen by arch-rival Acorn for a 16-bit second processor, but this was impressively late.

Meanwhile, Sinclair's decision to not provide a cassette port for the QL seemed to be actively deterring some software houses, as Imagine, CRL and Micromega had all switched to targetting arch-rival Amstrad's new Ambit-designed machine instead - helped as well, no doubt, because Amstrad was targetting the more-lucrative games market[8].

Sinclair had been famous for producing "highly novel, idiosyncratic products" and as Boris Allan wrote in Popular Computing Weekly in early 1984, it had been said that if Sinclair did not exist, then somebody would have to invent him.

Sinclair had added "a sense of the magical" to personal computing and his personality was very much the driving force behind the company's early success.

However, Sinclair was launching into a very different market, which was already well supplied with business machines and where Sinclair didn't have its "small, cheap computer" advantage that it was used to, and it remained to be seen whether Sinclair's rejection of the IBM market was a good move[9].

The company clearly believed it was, as back in 1983 MD Nigel Searle had said "We have been fairly successful by being different and we will most likely do the same for any new market"[10].

Let's do the time-warp again

The fact that it was code-named the ZX83 but wasn't actually announced for sale until January 1984 and didn't actually ship until late April of the same year hints at the controversy that surrounded its early announcement and late delivery - said by Popular Computing Weekly to be the worst delivery delays since the BBC Micro.

By the end of February, the first orders placed under an optimistic presumption of "28 days delivery" were starting to expire, with no sign of the QL.

These customers were sent a letter advising them that hopefully orders would be fulfilled by the end of April, which meant - for some - an additional wait of some nine weeks.

Nigel Searle said of this that "We realise that the time between now and then will be frustrating but we are confident that the QL will be worth waiting for and, of course, we will do everything possible to beat our target date for despatch"[11].

Sinclair had already blown out on a revised February delivery promise, made when production delays first surfaced, for the end of March - an estimate backed at the time by Sinclair's MD Nigel Searle[12].

By the very end of March, a QL had actually appeared at the Sinclair Education Exhibition, but even it had mysteriously disappeared by the second day of the show[13].

At the time there were thought to be no more than a handfull of production QLs in existence.

To really stick the boot in, when the first machines arrived with actual customers at the end of April 1984, they were greeted with a 1983 copyright message when the machine first booted up[14].

The delays also had an unintended and embarrassing side effect when Sinclair was finally forced to admit at the beginning of March that it was earning quite a bit of interest on customers' money and that this interest would "ultimately accrue to the company".

About half of the 9,000 orders so far were paid for by cheque and these cheques had been cashed.

It was expected that by the end of April Sinclair would be sitting on £1.8 million of customer money, which was held in a "Readers Trust Account" and would have earned about £32,000 in interest.

When quizzed by Popular Computing Weekly as to whether this was fair or not, a Sinclair spokesman commented "I do not think I am in a position to answer questions concerning ethics".

Meanwhile, all pending advertising had either been cancelled or quietly amended to remove the "28 days delivery" claims.

Sinclair said "Everyone is fully aware of the situation and has been given a full option to cancel their order"[15].

There had even been rumours floating around in the press that the cash from advanced orders was actually being used to finance the machine's development.

Sinclair was quick to refute this, suggesting that whilst Sinclair could not "afford to build thousands and thousands of machines and then launch six months later", it was nevertheless "a wealthy company" which didn't need to take in customers' money in advance to fund its operations, or as Sinclair put it "we are not in it to try and seize people's money".

He also seemed perplexed at the criticiscm, as the company had written to all of its pre-order customers offering to refund their money at any time, but apparently very few had chosen to do so.

As Sinclair went on to explain "what else are we going to do with the money? We have got to put it somewhere. We do get interest on it - what else should we do?"[16].

--

The ZX83 code-name seemed to have stuck around despite ZX Spectrum designer (and now ex-employee having left to start Jupiter Cantab) Richard Altwasser's assertion a couple of years before when the Spectrum was being designed that it was not going to be called the ZX82 because:

"calling the Spectrum a ZX82 creates the impression that the company will be producing a ZX83 in the spring of 1983"[17].

As it happened, some in the press thought April 1984 should have been its launch date all along, with the initial optimistic January date suspected of being a rushed Sinclair "pre-emptive strike" against Apple's new Macintosh[18].

Popular Computing Weekly suggested much the same when it said that the machine's release - despite the massive delays - was still six months too early[19].

Its price of £399 (£1,680 in 2025) put in competition with a raft of new £400-£1,000 business micros expected from Japan and also put it up against the venerable BBC Micro, however it also put it outside the price that gave Timex of the US the rights to any "personal computers" that Sinclair sold for under $500, as part of the two companies' distribution agreement.

This left Sinclair free to potentially exploit the lucrative North American market by itself[20].

The deal, which was quite far-reaching, according to Popular Computing Weekly, meant that Timex was free to either sell Sinclair's micros as they were, fiddle around with them, or to even produce entirely new micros based on the underlying Sinclair designs.

It also allowed Sinclair to sell its own machines in the US as long as Timex's sales remained under a certain threshold, however there was a catch: if any of Timex's variants exceeded this threshold then Sinclair wouldn't be able to sell any of its machines in the US, including the Spectrum, which it hoped to launch in the States early in 1983.

At the time though, Sinclair was more worried about production difficulties and meeting demand in its home market, as well as getting the Spectrum through rigorous FCC tests[21].

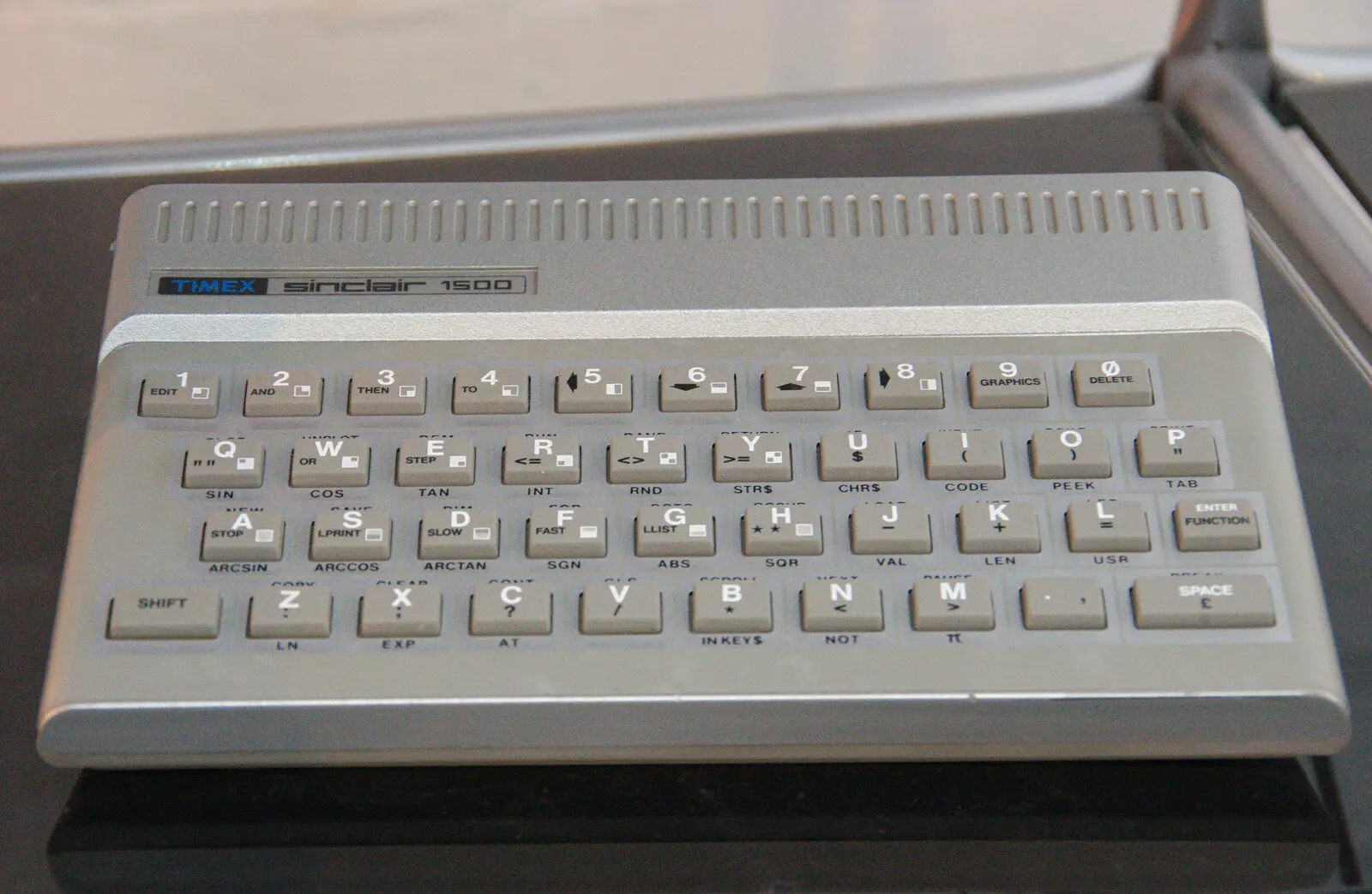

A Timex/Sinclair 1500 at the Centre for Computing History, Cambridge, in 2019

Timex times out

This issue became somewhat moot when Timex announced at the end of February 1984 that it was exiting the US home computer market entirely, and as a result would no longer be selling its Sinclair-designed TS1000 (ZX81), TS1500 (16K ZX81) and TS2068 (48K Spectrum) models.

This made it the third large micro manufacturer in the States, after Texas Instruments and Mattel, to succumb to the raging price-war that Commodore had kicked off the year before. Timex's VP Marketing and Sales C. Michael Jacobi said:

"We believe that the instability in the home computer market will cause prices to continue to fall during 1984, making it difficult to make a reasonable profit".

Sinclair's MD Nigel Searle had been in talks with Timex in the US the week before, but following the news announced that Sinclair was now not going to market the QL through Timex anyway, although this was less to do with Timex's performance than the fact that Sinclair itself was a lot bigger and more confident than it was a couple of years before, and seemed keen to have a go at cracking the US by itself.

Meanwhile, A Sinclair spokesman commented "The home computer marketplace is still very shaky over there".

The news also had a knock-on effect on software houses that were dependent on the Sinclair clones selling in the US, in particular Psion which had several packages for sale for the TS2068.

Less affected was Quicksilva, which also made software for the Commodore 64. Spokesman Mark Eyles said:

"It is sad that Timex has given up - lots of British companies spent a great deal of time and effort trying to support Sinclair out in the US and it looked like it was just beginning to take off. We will just have to hang on and wait for the QL".

Just like everyone else then.

Timex's Osborne moment

A Timex Sinclair 2068, © Popular Computing Weekly 15th September 1983It was revealed that Timex's difficulties went back to the beginning of 1983 when, in very much of an "Osborne moment", it showed off a Spectrum at the Winter CES in Las Vegas.

Sales of the TS1000 duly slumped and by April Timex had to drop the price to the equivalent of only £38 after a £10 rebate, or £160 in 2025, to try and revive sales until the now-delayed TS2000 range made an appearance.

Timex Computer Corp's VP Daniel Ross said:

"We are committed to remaining the price/value leader in personal computers ... No personal computer manufacturer offers more to the retailer in terms of profit potential"[22].

However it wasn't until the following November that the 2068 (Spectrum) appeared in US shops.

This was some 18 months after the launch of the Spectrum in the UK, as Timex had insisted on fiddling around trying to improve the Spectrum's design instead of releasing it as soon as it was available.

At the time of the launch of the 2068, Timex, of Waterbury, Connecticut, was expressing an interest in becoming a micro designer and manufacturer in its own right, in particular as it had a large workforce and a number of factories but was facing a shrinking market in its core wristwatch market[23].

Timex never released any sales figures for its Spectrum, but it was an open secret that very few of the machines were sold[24], with Popular Computing Weekly suggesting that Timex had sold only 40,000 2068s by the end of 1983.

The company was proving just too big to move quickly on anything - and agility was proving vital for survival in a fast-moving market[25].

Retailers had been stuck with surplus TS1000's for the duration and could not be persuaded to take the 2068 even when it was finally available.

It wasn't a total disaster though, as Timex did announce that despite exiting the micro market with its own machines, it was continuing to manufacture other companies' micros, which was handy as Timex's Dundee outpost was where Sinclair's machines were made.

Sinclair was hoping that the loss of Timex would not affect its plans for the QL in the US, stating with an admirable head-in-the-sand bravado that:

"We do not believe that the problems in the US home computer market affect products in the price range of the QL"[26].

Sinclair at the time had a presence in some 50 countries around the world with an impressive 40% of its turnover coming from foreign markets - something that was considered unparalleled even amongst its Japanese competition.

It was also still hoping that it could succeed with another crack at the "plum" US market, despite the failure with Timex, with Sinclair suggesting that:

"we are the only people who stand a hope in hell of getting into the American market [because] we are the only people outside America who have a lead over American technology".

This belief was based on a comparison of the QL to Apple's Macintosh, which Sinclair considered was very similar to the QL, albeit with "vastly different technology".

On the other hand, the QL was apparently a world leader because if you:

"open up a QL and open up a Macintosh they are just miles apart - in the QL it's all in a few custom chips, whereas the Mac is vast tons of standard chips"[27].

When the QL finally shipped, with the first few machines leaving Sinclair distributor GSI's Camberley warehouse via courier and first-class post on the evening of Monday April 30th[28], Sinclair offered those early down-payment-buyers a free RS-232 lead (worth £14.95, or about £63 in 2025 terms) as compensation, which given that nearly five months was just a little longer than the promised "28 days delivery" was perhaps a little cheeky.

Your Computer quipped that those waiting more than 28 days for their QL thought it must stand for "Quite Late"[29], whilst Popular Computing Weekly suggested "Queue Longer"[30], Quantum Libet (Latin for "as much as you please") or "Quick Lash-up" - rumoured to be its actual nickname within Sinclair Research itself[31].

Personal Computer World suggested that it meant "A long Q and an L of a wait", whilst positing that "the 28 days promised delivery time was not calculated using a QL"[32].

Blob of metal

Reasons for its late shipping, which Sinclair had originally claimed was because of "phenomenal demand", included the QL's custom ULA chip requiring last-minute modifications, as well as issues with integrating Intel's 8049 keyboard controller[33].

The keyboard itself wasn't considered appropriate for business use as it was essentially still a membrane keyboard underneath.

Sinclair had had samples of conventional keyboards produced, but chose to do it "his own way" as it was part of the QL's "innovation" - even though a real keyboard would have cost only a few pounds more[34].

The most significant reason for the delays was that Sinclair couldn't actually get all its BASIC and Operating System ROM software to fit in to the 16K of onboard chips set aside for it, rumours of which had been doing the rounds since February[35].

As a work-around, the first few thousand machines were sent out with a hacked-in "blob of metal", slightly larger than a matchbox sticking out of the expansion port at the back and which containing an overflowing 8K of BASIC ROM, which engineers were forced to commandeer as a temporary solution.

The expanded space requirements meant that even once the overflow was moved back in to the final ROMs, the machine would only be capable of supporting just 16K more of ROM via the expansion socket - half the intended amount[36] - thanks to the QL's design-limit of 64K ROM address space.

Explaining the engineering hack, a Sinclair spokesdroid said:

"As far as customers are concerned, they want the machine they thought they were buying as soon as possible - and this is a way of doing that".

There were 13,000 customers waiting for QLs at this point - up 4,000 since February[37].

Sinclair eventually had to break cover to speak out against ongoing criticiscm against the increasing delays in the QL's appearance, going as far as to suggest that Sinclair was actually better than other companies in meeting its promises.

Contacting Personal Computer News in order to "set the record straight" after its withering appraisal a couple of weeks before, he suggested that:

"we are not going to let people down. We will make sure of that. Criticism is inevitable I suppose, it is just that sometimes it is less fair than others".

Sinclaire went on to compare the company's delivery problems with Acorn, where the Electron was months late in a situation that, according to Uncle Clive, barely raised a grumble.

There was also the IBM PC, which was delivered three months late (or well over a year if you count the time before it reached the UK) and the situation at Commodore, which still hadn't shipped machines it had announced in June the year before.

He did however concede that there had actually been a delay, but claimed that the company was:

"now shipping and I think it has been unfair - or unbalanced - in that everyone is suggesting that it is some colossal catrastrophe. We are not proud of it and we don't like being in this position, but we are no worse and indeed are better than our competitors in this respect, despite the fact we are launching an enormously more radical machine".

On around the 9th of June, the end of the "metal blob" was in sight as the final version of the machine's software was announced as finally shipping, albeit first on EEPROM until actual ROMs were due to appear another six weeks later.

That definitely put shipping of anything like the final version of the QL well beyond the original "28 days".

In an interview with Personal Computer News in its June 16th 1984 edition, Sinclair attempted explain where the company had gone so wrong with its timing:

"A launch date had to be set quite a while ahead, and obviously you think you are going to get everything ready on time, but you can't always. You can't afford to veer too much to the side of caution because otherwise you have got no orders to ship against".

He went on to explain why the machine was also released with incomplete and not-fully-debugged software, claiming that it would have been surprising if there hadn't been any hiccups when shipping "very complicated machines [which were] such an enormous change from what was available previously".

Personal Computer News had suggested that the QL was "ludicrously easy to crash", to which Sinclair responded by suggesting that:

"no new computer with new software is totally free of bugs. All you can hope for is to be free of significant bugs".

Uncle Clive went on to say, clearly using some definition of "early" which allowed for a being a few months late, that:

"In a sense, by shipping the machines out to customers early we are getting them to find those bugs for us. We are telling them to let us know if they find any bugs - we are not talking major bugs here, just the detail".

Sinclair had shipped its brand-new operating system and software in what it reckoned was record time - 14 months from conception until it was actually debugged.

The "early" shipping of the interim version was apparently because Sinclair thought that it was better to do that than wait until it received the actual final software, and in a frankly surprising admission Sinclair even suggested that:

"the whole point about the software was that it wasn't final, and it wasn't final in the sense that it was crashable"[38].

So that's alright then.

Tonto and the ICL One Per Desk

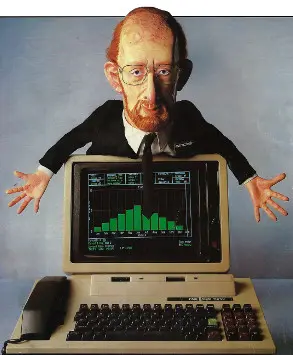

Front cover illustration of Clive Sinclair and an ICL "One per Desk", based on Sinclair tech. © Personal Computer World December 1984The QL project itself had originally been envisaged as something completely different, utilising Sinclair's flat-screen TV technology and the infamous Microdrives.

Interviewed back in November 1982's Your Computer, Clive Sinclair said of the rumoured Osborne-influenced ZX83:

"We have the flat-screen technology, we have the Microdrive technology. Late next year we'll have a machine which is not a replacement for anything we have now and which will have the display and the drives. It is for that reason that I don't think our opposition stands a heck of a chance, because we can do that and no-one else can".

It was also suggested it would have a built-in modem, similar to Sinclair's £50 (£230 in 2025) unit, with Clive saying:

"When you're linked to the telephone you can send a message from one computer to another, so you've got electronic mail".

A modem also gave access to Prestel, which Sinclair thought was:

"a good way to sell software, the sort of thing we're doing will probably be a great boost [to the service]"[39].

This portable version never materialised, but some of the same ideas did find their way into a project that Sinclair was doing for ICL - the desktop excecutive machine known as the "One per Desk".

Sinclair offered proof that the dream of the paperless office has been around for as long as computers, as he said of the OPD that:

"It will replace the paper that moves around at the moment. An executive can send data to anyone else in the net, receive messages on it, and his mail with come through there".

The ICL OPD - One Per Desk - from Personal Computer World, December 1984

The OPD had been developed by a team of around 50 in ICL, with the company having spent £10 million over 18 months up until the end of 1984 on tooling, design and research, the latter in conjunction with the University of Warwick.

Thanks to the black and white display used during its early development, it was apparently known as "Work Station Zebra"[40], a pun on the espionage film Ice Station Zebra.

It had originally been rumoured that it was going to be essentially a complete re-badged QL, however when the thing launched all that remained were the Microdrives, a couple of ULAs and a modified version of the QL's SuperBasic, plus the same 68008 CPU.

A the time there were thought to be 400,000 IBM PCs and 300,000 other micros already installed in British industry, with ICL targetting no fewer than 600,000 managing directors for its new machine.

It also had an extended version of the Archive/Quill/Abacus/Easel bundle that shipped with the QL, but in ROM so task switching was pretty instant.

Unfortunately, although the OPD's ICL operating system was capable of real multi-tasking, the Psion software didn't actually make use of it.

Instead, the running application could be halted at any time to switch over to the telephone - which included a computer-generated answering service thanks to the OPD's TI 5220 speech synthesis chip with its 152 word vocabulary - or the built-in modem and then switch back to where the previous program had left off[41].

Somewhat unexpectedly, the One per Desk actually won an award at the British Microcomputing Awards in May 1985, where it took the London Standard Hardware Awards of the Year top prize.

Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World was taken aback, citing that the OPD, although advertised as a CP/M machine, took four minutes to load CP/M over the network and worse, the Tonto, as it was also known, took 172 seconds to execute a 1,000-step for:next loop which the BBC Micro took eight seconds to do.

Kewney reckoned that the only reason the thing sold at all was because it was on ICL's approved products range so that every time ICL sold a mainframe, they also sold a load of the things that "went with it"[42].

The QL itself would also go on to win a gong, when it picked up the Personal Computer World-sponsored award for Home Micro of the Year in the summer of 1985[43].

The Tonto also reviewed quite well, with David Tebbutt writing in December 1984's Personal Computer World that:

"The ICL OPD is an excellent concept. It grabs a corner of the desk and, with the Xchange software, takes care of most of the professional's data processing and telephone needs. The price is simply amazing coming from ICL - I haven't seen anything like this machine at that price level and I suspect that, for a few months at least, ICL will have the field to itself".

In the same review, it was mentioned that ICL's Robb Wilmot was hoping to shift 250,000 OPDs during 1985[44].

Tried and tested

Back in the autumn of 1983 it was looking "likely" that along with the flat-screen built-in monitor and dual Microdrives, the new Sinclair machine would also be dual-processor, with an additional Z80 for Spectrum compatibility.

As Sinclair MD Nigel Searle said, in advice that in hindsight Sinclair should probably have listened to:

"You don't want to change all the variables at once. In order to be competitive you have to change, but you want to take tried and tested methods with you".

Searle continued to discuss how Sinclair was not planning on going with some off-the-shelf operating system, saying:

"I am very anxious not to appear negative about [Digital Research's] VIP or Personal CP/M, but we will continue to go on our own eccentric way".

In September, IBM's rumoured PC Jr, a.k.a. Peanut, was the current threat which Sinclair was monitoring closely. Searle concluded:

"It is not necessarily true that we will do well by making ours an IBM compatible product. We have been fairly successful by being different and we will most likely do the same for any new market"[45].

Not suitable for business or pleasure

The application software for the QL was written by Psion - a company which would later go on to produce both the famous Psion Organiser series and the EPOC operating system which led to Symbian, the operating system used on countless zillions of Nokia phones.

The company was already working on an application suite when it was first approached in the spring of 1983 to produce the software for what was then known as the ZX83 - a micro which Sinclair was pitching at the time as a kind of "people's computer, designed for real applications like word processing and so on".

David Potter of Psion suggested that the ZX83 was probably not powerful enough to run then software as a suite, but that it would work if split up into four separate components, an idea which Sinclair liked.

It was at this time that part-nationalised behemoth ICL also signed a deal with Psion for its software for use on its One Per Desk computer. Potter said of the deals involving two of the most-dominant companies in UK computing that:

"For little Psion to sign these huge contracts in which the software would be exclusively on every single unit, so we would be getting royalties on every single unit, was of huge potential to us, so that was exciting".

It would also be somewhat dangerous, as the company was now somewhat held hostage by the fates of both the QL and ICL's OPD. Neither computer fared well, although as Potter said:

"The concept was right, as Amstrad later showed with the [PCW 8256] word processor. It was the execution that was wrong".

As there was no hardware available, Psion had to invest in a development system based on a DEC VAX Minicomputer. This could emulate different processors, including the 68008 of the QL, which meant the company could develop its software before the QL was ready.

This was just as well as the QL itself was hideously late, finally shipping on the evening of Monday 30th April 1984, in the process making a mockery of its previous working title of ZX83.

Sinclair started supplying bits of the hardware and operating system to Psion around November of 1983, which was when Psion could finally start porting it and testing it for real. However, as Potter recalled in his Personal Computer World interview:

"I went away on holiday in December 1983, and while I was away I got a telephone call from Charles [Davies] saying 'They're absolutely mad, they say they're going to launch the ZX83 [in] January and they want all our software up and running'. I said they're daft, but I got on an aeroplane and came back because that's what they'd decided to do and it wasn't for us to stop them. Anyway, they had this huge launch, very impressive, and then nothing happened, and they started getting cheques, and no machines, nothing, and we were horrified. Time went by. Eventually they started getting slated in the press and on, I think, 31st March, they had to say they were going to ship. Then in April they came out in dribs and drabs and of course they weren't working properly and there were all kinds of problems[46]".

With the complete software suite from Psion and some good hardware specs, some reviewers quite liked the QL, once it had actually started shipping.

Tim Hartnell, writing in June 1984's "Your Computer" said:

"You're going to like the QL. As with all Sinclair products, it may display quirks and annoyances which are not immediately obvious, and the slow access times of the Microdrives may annoy you, but overall it is a fascinating package".

However, he also said, tellingly, that "...and yet I sense that the time for foisting unproven products on the market-place has gone".

Other reviews were less favourable. Writing in July's "Your Computer", Kathleen Peel said of the initially-released (the "FB ROM") machine that:

"it was not really suitable for business or pleasure as it had far too many faults and kept crashing. It was slow, had an unfriendly editor, the microdrives were prone to lose files and data, microdrive files in a well-used cartridge would take an age to load".

A test of program loading showed that even though the updated ROM (version "AH", delivered in June 1984 and which meant there was no longer a lump sticking out of the back of the QL[47]) knocked 30 seconds of a large program load, it was still taking around 40 seconds, whereas a 48K file on a Spectrum using Microdrives only took seven seconds.

That said, the updated review rounded off with:

"it must be conceded that the hardware repesents the ultimate in technical achievement in the under-£400 range and probably some way beyond"[48].

Phi Mag Systems' Phloopy - quite similar to Sinclair's Microdrive, but aimed at the BBC Micro. From Acorn User, September 1984

Microdrives, which had been promised over a year before they were available, were Sinclair's mass-storage device of choice and implied a resemblance to 3" or 3½" floppy drives, despite actually being just an endless loop of tape in a tiny plastic case - a format sometimes known as a "stringy floppy" and similar to other systems like Phi Mag's 9-track 100K Phloopy, available for the BBC Micro[49].

They were one of the factors why the QL failed to do well, as they were completely non-standard.

The QL was also launched as a business machine when the business market was becoming almost entirely IBM PC and it didn't help that the Sinclair machine was also considered a bit toy-like, which was perhaps not surprising given Sinclair's heritage.

Furthermore, existing Spectrum owners wouldn't upgrade to it as there were no games available.

Early Imagine advert for its Spectrum and VIC-20 games Arcadia, Schizoids and Wacky Waiters, © Personal Computer News April 1983

Sinclair had tried, at least briefly, to fix the lack of games by buying up the Bandersnatch "megagame" from the crashed Imagine Software.

After the Sinclair aquisition of Bandersnatch, which was confirmed during October 1984, several ex-Imagine staff - including former directors Dave Lawson and Ian Hetherington, as well as Evans, Tom Flannery, Michael Glover and Andrew Sinclair - set up new company Fire Iron in Liverpool to develop it and the various other Megagames on behalf of Sinclair.

However it was not as a ROM cartridge as had been originally planned[50], most likely because the QL could now only support 16K ROMs anyway following the "fix" for the overflowing-operating-system issue.

By April 1985 the game still wasn't ready, and so Sinclair pulled its funding and cancelled the contract. Bandersnatch eventually re-surfaced for the ST as the game Brataccas, produced by Psygnosis, which formed out of Fire Iron when the original game was dropped[51].

In the spring of 1985, Sinclair released Version 2 of the bundled QL software which had been developed by Psion, in a tacit admission that the original release was flawed.

The new versions loaded twice as fast, ran 20-30% faster and actually used "machine code", a claim which strongly implied that the original versions had been written in BASIC, albeit a compiled version.

At least it loaded quicker until a conflict with Sinclair's SOS - Sinclair Operating System - was revealed. The issue caused documents longer than 32,767 characters, or around five and a half thousand words, to hang the QL on a save.

Psion blamed that fact that QDOS wasn't behaving as the manual specified, but anyway released a patch fixing the issue but at the same time restoring the previous slow save speed.

Sinclair reckoned that this was clearly OK because "[Quill] was not designed to be a mega word processor"[52].

Sales disaster

It was reported that sales for the whole first year of the QL's life had been a "disastrous" 50,000 units, but that the company was still optimistically aiming for sales of 200,000 units in the UK alone during 1985.

At an all-day seminar said to have been "more like a religious rally", Strathclyde University's committment to take 7,000 QLs - one on the desk of every student - was announced, along with news that Sinclair's Nigel Searle was being dispatched to the US to head the mail-order operation over there.

Clive also said of Jack Tramiel's Atari:

"we are not impressed by the competition. I don't believe that Tramiel is in a position to compete. Realistically, he is at least a year behind us"[53].

The Baron of Beef in Cambridge - legendary, if mis-attributed - site of a punch up between Clive Sinclair and Chris CurryAtari UK's marketing director Robert Harding was quick to retaliate, accusing Sinclair of "sour grapes" and suggesting that "Sir Clive tried with the QL and it hasn't succeeded".

Whilst Sinclair did admit that 1984 had been "a tough year for the QL", he reiterated his optimistic forecast for the following year by saying that "85 is going to be the year of the QL", whereas Sir Clive reckoned that the ST would be "late and disappointing"[54].

Needless to say, the Atari ST was much more successful than the QL, selling about 2.1 million units over its life[55] versus the 150,000 of the QL.

At least the insult trading didn't end up with Your Computer's suggestion, which was that the two companies settled their differences over 15 rounds in the Baron of Beef - a reference to a punch up between Sinclair and Acorn's Chris Curry in a pub in Cambridge.

Meanwhile, games for the QL were still limited to only chess, backgammon and bridge[56].

The QL's version of chess was based on an algorithm by Richard Lang, winner of the World Microcomputer Chess Championship throughout most of the 1980s[57] and was written by Psion, who were thus claiming at the end of 1985 that it was still "world champion"[58].

Blackjack (which retailed for a price-gouging £19.95, or £80 in 2025 money), Quest (a game originally found on ACT's Apricot) and a Sprite editor were released in May.

There was also a bit of a splurge in the release of computer languages for the QL as Pascal, Forth, an assembler/monitor, APL, BCPL, Lisp and a C compiler were all released around March[59].

Curse of the Microdrive

One of the reasons for the lack of software was said to be the curse of the Microdrives - not just for the non-standardness that they presented, but also the trouble that publishers were finding in getting decent, reliable and cheap Microdrive duplication[60].

This was an issue which had been a problem since at least the end of 1983, when the eponymous owner of Richard Shepherd Software - the company that was thought to be the first to offer software specifically for the device - reporting that whilst it had been planning on offering Microdrive-based software straight away, there was "no easy way of duplicating large numbers of the micro cartridge".

The company got around the problem by shipping on cassette and offering a "save-to Microdrive" option[61].

Shepherd was by no means alone, and the problem was still as bad by the summer of 1986, with software companies like Softek still shipping programs primarily on cassette with the option to transfer to Microdrive[62].

By the summer of 1985, Sinclair seemed to have capitulated somewhat over its most vexatious issue by announcing, in what seemed like a major u-turn, that it was bringing out a 3.5" floppy disc drive under its own name.

The disc itself was manufactured by Microperipherals and had actually been available for a while, with Richard Miller of Microperipherals saying

"it's not a new disc drive, we've been shipping since March. Sinclair has been interested in badging a disc drive for about seven months now, so we were very pleased to get the contract".

Popular Computing reckoned that this meant that Sinclair had decided that a Sinclair-badged drive would boost sales, whilst a continued reliance on Microdrives would not[63].

During the summer, there were ongoing rumours about a proposed QL II, which it was thought was being (or at least should be) designed to take on Atari's 520ST.

This speculation was fuelled in the late summer of 1985 when it was confirmed that Sinclair was once again in talks with Digital Research over DR's GEM graphical operating system - as used on the Atari ST - although DR's Frank Iveson was somewhat cagey when he said

"We have always been having discussions with Sinclair, but as yet the outcome has not been decided. We'd certainly like to see GEM on the QL - it would help to stabilise the software industry. GEM could be ported straight across to the machine; it wouldn't even need to be compiled"[64].

The QL was discontinued in 1985 and Sinclair's name was bought by Amstrad in 1986. David Potter in his December 1991 Personal Computer World interview put Sinclair's failure down to the QL, but also to the company's enigmatic leader Clive.

With the lateness of the QL's delivery leaving the company's image in taters, Potter said of it that:

"the concept was right, as Amstrad later showed with the [PCW 8256] word processor. It was the execution that was wrong. Sinclair himself was interested in markets. He's got this boffin image and he husbands that himself, but the key to it is that he's got a great marketing nose. He knows a lot technically behind the thing but he's no engineer. He's a marketing boffin and an engineering buffoon. Even the Sinclair Spectrum, which was a hugely successful product, the production yields on that were always dreadful. It had to be re-engineered by Timex to be manufactured in volume, and the product never stood up in the field anyway. It's not just true of the Spectrum, it was true of the ZX81, it was true of the Black Watch, it was true of the calculators. You know, there were all these stories of these caluclators blowing up in ambassadors' pockets. I think this was a great weakness[65]."

Potter considered that such "inattention to detail, this over-excited undisciplined dash for new markets" was responsible for the downfall of not just Sinclair, but nearly all the companies born out of the micro boom of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

On a more positive note, Linus Torvalds attributed part of his developing the first Linux kernel to the fact he owned a QL and had to write a lot of his own software for it as no-one else was[66].

It had retailed for £400 - about £1,680 in 2025 money, which for a machine with 128K supplied as standard and a 68008 processor was actually pretty good value, but by the end of August 1985 it was down to half the price at £200 in a last-ditch attempt to shift units.

Some of the machine's failings were said to be down to its support chips, as machines like the Atari 520ST and Commodore's Amiga - based around what was largely the same processor - were far more stunning beasts.

David Kelly of Popular Computing Weekly said "The more you see of these [other] machines the more one realises how horribly wrong Sinclair went with the QL"[67].

Back to the C5 future

Clive Sinclair and his C5, © Your Computer, 1985In a surreal footnote, whilst the QL was crashing and burning, Clive Sinclair was talking about a trip from John O'Groats to Land's End in one of his other pet projects - a C5 - the infamous electric tricycle-cum-mobility-scooter produced by offshoot Sinclair Vehicles, a separate company which had been set up by the proceeds of the sale of 10% of Sinclair Research itself[68].

As outlined by managing director Barry Wills, the C5 had been designed as a personal transport with "lightweight materials, good aero-dynamics and conventional battery technology" in mind.

For some, the choice of lead-acetate battery was a bit of a let-down as back in 1983 it was "an open secret" that Sinclair had been working on other "advanced battery technology" for his then-nascent electric car.

Sinclair Vehicles was also planning a range of extras, including "booster pads" for smaller drivers and a high-visibility mast, like one of those bicycle trailer flags, so that other vehicles that were more than 80cm high could actually see you.

When the car which would become the C5 was just getting off the ground, after years of development, Sinclair even bought an option in the defunct De Lorean car factory in Dunmurry, Northern Ireland, as a factory location on account of it possessing one of the most "advanced plastic-moulding systems in Europe"[69], an option that for Back to the Future fans it sadly let lapse.

The C5's body was the result of two polypropelene mouldings which were electrically melted together, so having its own moulding production line would have come in handy.

The following year, in 1984, Sinclair Vehicles moved to the newly-opened University of Warwick Science Park, where it became one of the park's first occupants.

The site, which was close to the centre of what was then the UK's motor industry, became the centre of project management for the C5[70], which had been designed in conjunction with Lotus Engineering. Barrie Wills said of the early engineering phase that:

"Everyone that saw and drove the C5 during and after its engineering and development by Lotus Engineering was impressed".

Even Stirling Moss, former racing driver and now motoring journalist, was apparently "full of praise" for the electric tricycle.

Meanwhile, Wills continued in an interview celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Warwick Science Park in 2024, that:

"Had it been launched today in a slightly different form, benefitting from a change of legislation that has removed the strict 60kg weight limit, it could have been a success as the public is now familiar with electric vehicles, and cycle lanes on roads are commonplace[71]".

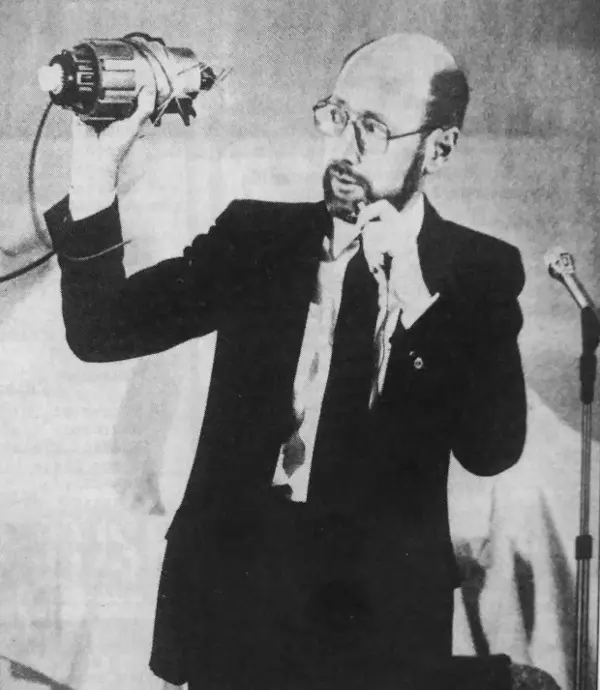

Clive Sinclair waves around a C5 motor, © Personal Computer World November 1988When it did appear, the C5 was said to have been somewhat compromised by having to comply with the "Electrically-Assisted Pedal-Cycle Regulations Act" of 1983.

These regulations limited the engine power to only 250 watts - with which it could do a maximum of 15mph - and a total weight of no more than 60 kilograms, but the trade-off was that anyone over 14 could drive one without insurance, tax or a crash helmet.

Its pedals also meant that if the battery ran out - the C5's range was 20 miles on an 8-hour charge - the owner could still pedal the thing home[72].

Perhaps its image wasn't helped by the fact that the C5 was made by Hoover in Merthyr Tydfil and that the Italian company Polymotor that made the engine also made washing-machine motors (as well as torpedo motors, a fact that Sinclair mysteriously mentioned to the press)[73].

This gave rise to the urban legend that the C5 was itself powered by a washing-machine motor.

At at least one point Hoover had to halt production of the C5 in order to replace a faulty part, with around 3,000 C5s being affected by a problem with plastic moulding on the machine's gearbox not being up to standard.

At the time, up to the third week in February 1985, it was estimated that 5,000 C5s had been sold[74].

Sinclair was planning "a family of pollution-free, economic, quiet electric vehicles" of which the C5 was "the baby of that family"[75] and had also been discussing his plans for additional models in the "C" range, including a 30mph, 40-mile-range two seater called the C10 and a 4-seater 80mph C15, available "by the end of the decade".

The C10, meanwhile, was expected to be available in 28 months[76], which would have been about July 1987.

Perhaps this oddly-specific number was an all-too-knowing in-joke at the expense of Sinclair's many famous "28 days delivery" claims which, in real-world time, was nearly always a lot longer.

A letter in Personal Computer World's August 1984 edition even attempted to calculate the scaling factor between "Sinclair time" and "real time", suggesting that a wait of 119 days for a QL meant that one Sinclair-day equalled six real days.

It wasn't just Sinclair that was notorious for delays, with Acorn being subjected to the same calculations with 42 BBC-days actually meaning 203 real days, or around five real days per Acorn-day[77].

The press launch for the C5, held in January 1985 at Alexandra Palace in North London, was a disaster.

Journalists who took their vehicles out from the nice, warm, exhibition hall for a spin in the great outdoors found themselves "hurtling out of control down icy slopes, almost disappearing under the wheels of lorries and having to pedal back up the hill after their motors overheated or the batteries failed". Your Computer even referred to it as the "bobsleigh".

In a 2010 interview with The Independent, Sinclair said of the launch day that:

"The ground was covered in snow and we hadn't realised that the batteries virtually packed up in freezing conditions. It was a crazy time to launch it. God knows why I did that"[78].

It didn't get much better after that: in the late summer of 1985, Hoover stopped production of the C5 over a financial dispute, then in the autumn, TPD - which Sinclair Vehicles had been renamed to - crashed with debts of £1 million. It went into voluntary liquidation on the 4th November[79].

In all, it was thought that Clive Sinclair had lost a total of about £8 million (about £32 million in 2025 terms) on the C5 and other electric vehicle project.

Perhaps it was not surprising that the press (although apparently not his official biographer, Rodney Dale, in the first offical biography that came out towards the end of 1985) was questioning how someone who had almost unilaterally created the UK computer industry could also create disasters like the C5, as well as the infamous "Black watch" and largely-failed flat-screen televisions[80].

Epitaph

In what in hindsight reads almost like an epitaph, at least for Clive of Sinclair Computers, since his company - which could trace its roots back to 1961 - was only months away from being bought by Amstrad, an editorial in Popular Computing Weekly, published in its 19th-25th September 1985 edition, picked up on Clive's influence:

"He created the whole micro boom in this country, starting with the ZX80 right up to the Spectrum. There is hardly a single UK software house - producing for the Amstrad, C64 or whatever - which doesn't owe its existance in some way to Sinclair. Without Sinclair there would have been no micro industry - at least not in its present form. He is responsible for putting Britain on the world micro map - let us not forget that"[81].

The QL itself was also subject of epitaph - or at least a post-mortem - some 18 months after its launch, in a retrospective published in March 1986's Personal Computer World. In it, Tony Ashford wrote:

"At the time of its premature launch, the QL must have taken the home computer industry by storm. Nobody could have anticipiated such high specifications for as little as £400. 128K of continuous user-accessible memory, multi-windowing, multi-tasking, two fast mass-storage media [devices] and four applications - another first - [and which were also being] sold for the IBM PC at £495. With perhaps the exception of the BBC, the other computers readily found in the major chain stores, such as the Commodore 64, Atari 800XL and Spectrum were still considered very much as toys, predominantly used for playing games".

The review continued with a test of the QL's Microdrives, which showed that they seemed to actually be quite reliable and could even be fast in the right circumstances, and that the Psion suite was actually quite good, but that it was inevitably compromised by the constraints of the QL - in particular that there was so little memory left over to optimise file-system management, making Microdrive access seem especially slow.

The retrospective concluded that:

"My main criticisms are directed towards the QL's poor press coverage. Beating the Japanese at their own game means producing better and cheaper products - not becoming literary kamikaze pilots with an (almost) inexplicable tendency to score own goals. Without any real competiion for over a year, the QL was ably suited to penetrate the US market in a big way; American reticence was understandable in view of the response given to the QL in the British press. I was happy to pay £400 for my QL. Price cutting is fairly standard in the face of competition but I doubt that the large drop in the price of a QL was not a consequence of its press coverage. If this is true, they have done no-one a favour - ask Amstrad. I have taken the press coverage given to the QL to date as an insult to my intelligence ... and at its new price of £200, it is more than capable of standing on its own three feet![82]".

Date created: 08 November 2013

Last updated: 05 April 2025

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2025. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.