Acorn Advert - September 1984

From The Micro User

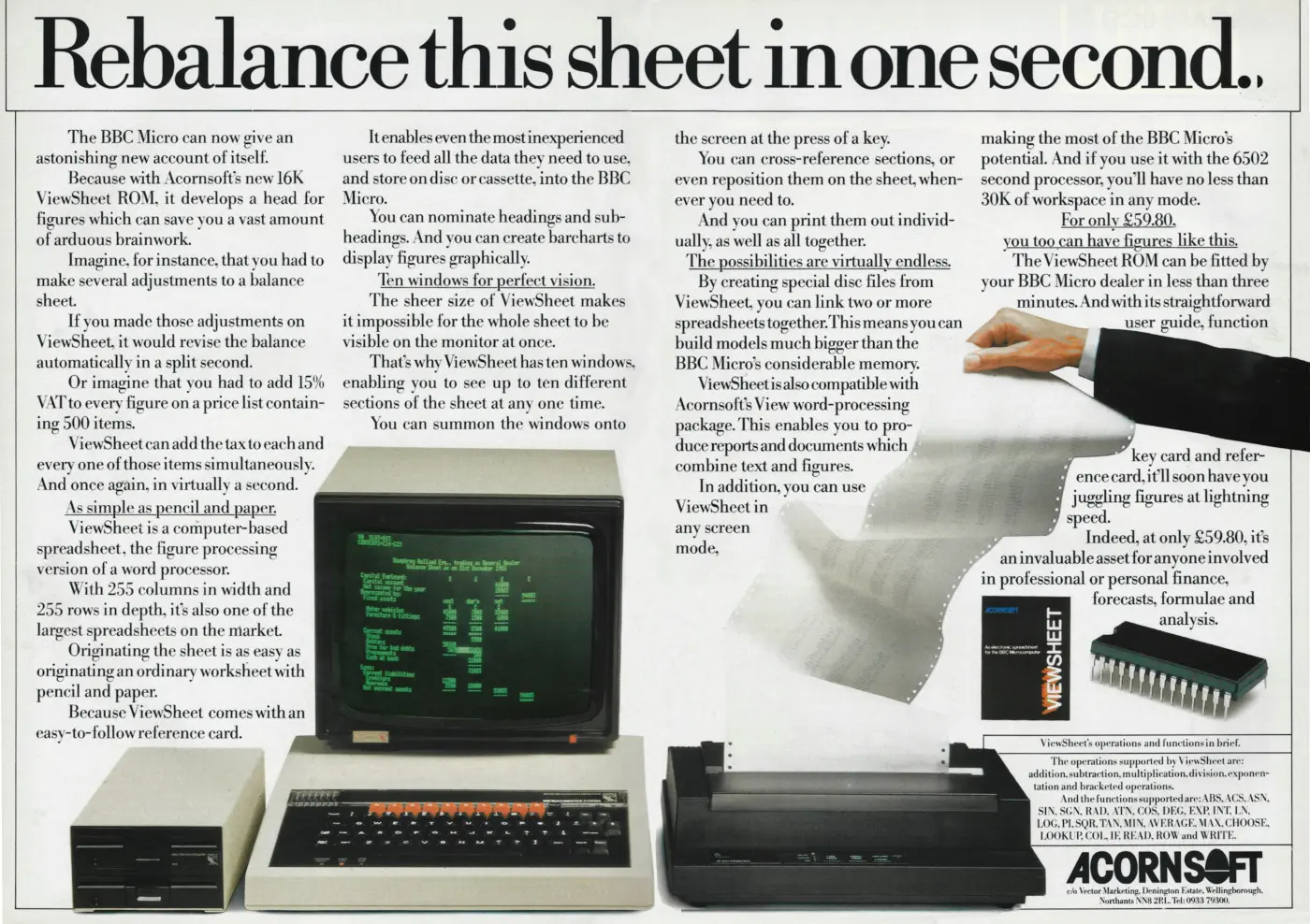

Re-balance This Sheet in One Second

Like several computers of the day, Acorn's BBC Micro could take software in the form of PROM - programmable read-only memory.

Some, like the VIC-20, could take it one-program-at-a-time in the form of a plug-in cartridge, whilst the BBC - like the Commodore PET - could accept a certain number of additional chips inserted directly on to the actual motherboard of the computer itself. These would then be permanently and instantly accessible.

This particular advert is of a plug-in spreadhseet called ViewSheet, likely modelled on VisiCalc - the first "killer app" that saved the Apple II back in 1979.

It retailed for £60 - about £250 in 2026 terms, or not totally disimilar to a fully-licenced copy of MS Office.

The BBC had four spare slots available, although access to most of these required removing the case.

However, at the July Electron and BBC Micro User Show, held at Alexandra Palace, Watford Electronics revealed its new Apex system, which allowed a total of 128 sideways ROMs to be added externally and 15 internally[1].

If filled entirely with RAM, it could support over 1MB - a huge amount for a computer whose base memory was only 32K.

Sideways ROM was a method of "bank switching" or paging memory. Each chip would co-exist in the same 16K block of reserved address space, but only one could be active at a time.

When questioned why anyone would want 128 ROMs resident at once, Kevin Edwards of Micro User's technical support team quipped "Easy. It's so you can have all the versions of the Watford DFS [Disk Filing System] in one micro".

An alternative, also at the show, was Viglen's sideways ROM cartridge system, which allowed "hot swapping" of sideways ROMs without having to open the case.

It provided a socket in the "ashtray" to the left of the BBC's keyboard - a pre-perforated chip-shaped cutout which could be removed to reveal a space in the case[2] under which was a single ROM socket.

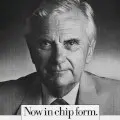

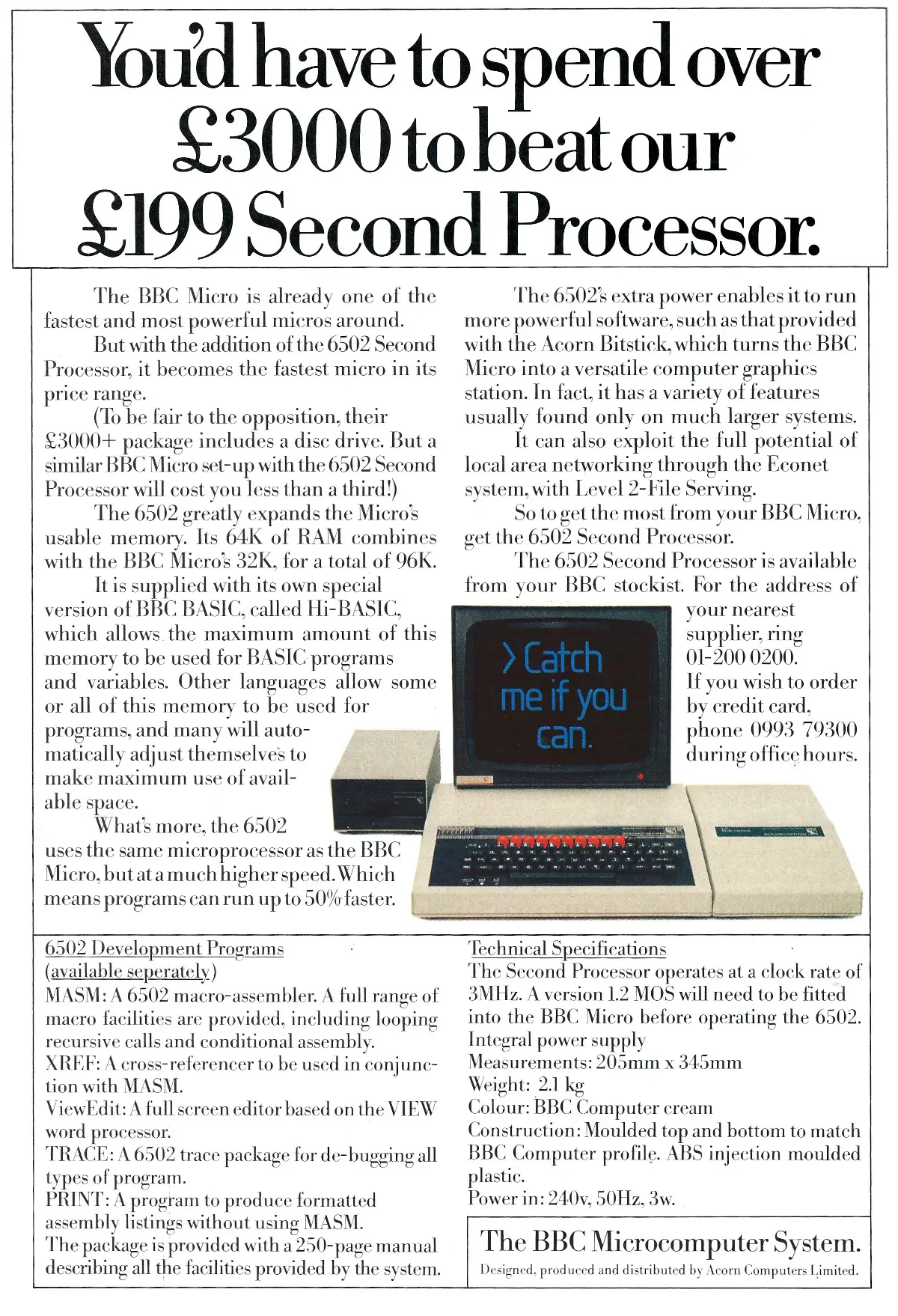

Catch me if you can: an advert for Acorn's 6502 second processor, retailing for £199, which is about £840 in 2026. From Acorn User, September 1984

In other chip-related news, Acorn had finally released its long-awaited second 6502 processor unit for the BBC a few months before in May 1984.

This turned the BBC into a "high-speed dual-processor system" and was attached to the host micro using the fast "Tube" interface.

The original 1975-designed 6502 ran at around 1MHz, whereas the BBC used the Synertek 6502A variant at about 2MHz.

The plug-in used the G65SC02 [3] CMOS variant at 3MHz, which because it didn't have to deal with I/O interrupts and had an extra 64K of memory meant it ran even more than 50% faster than the BBC it was attached to[4].

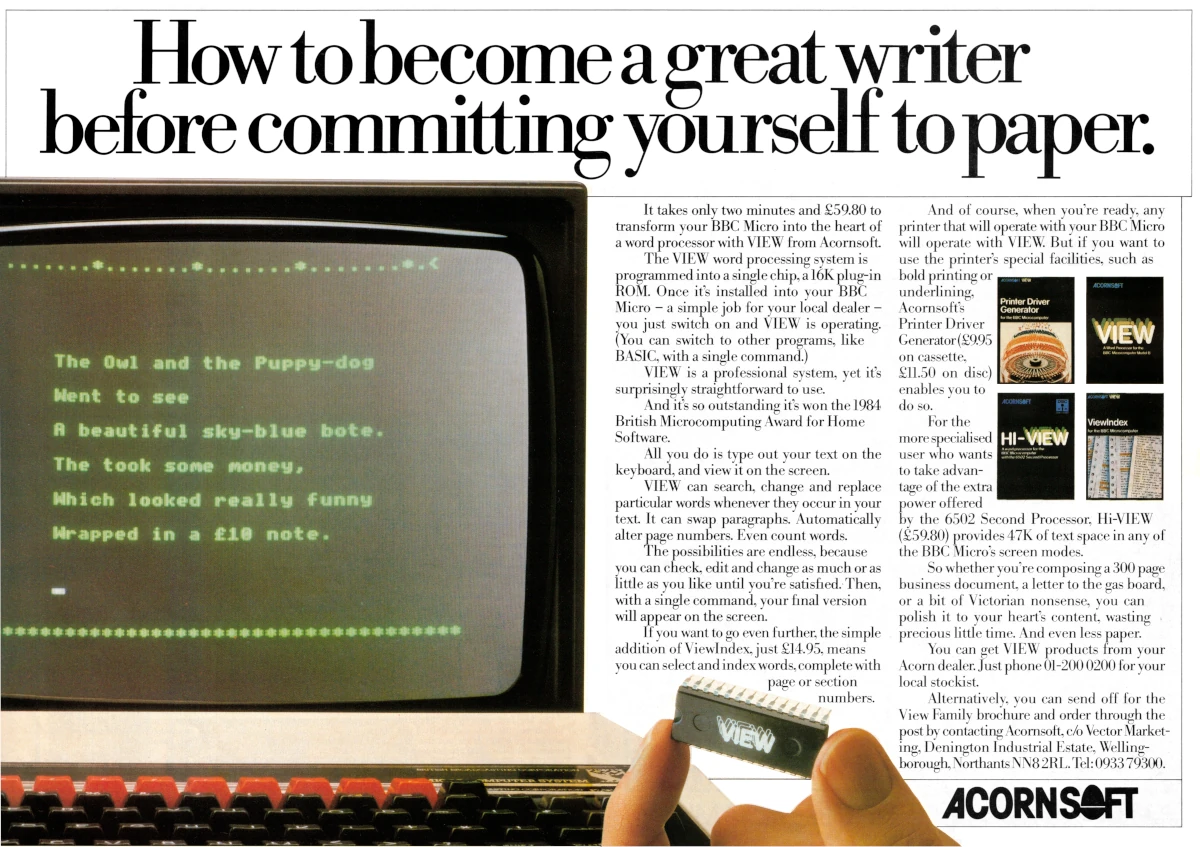

Another of Acornsoft's programs-on-a-chip, in this case the word processor View, available for £59.80, or about £250 in 2026. Also mentioned in the advert is a specific version of View called Hi-VIEW, which was aimed at users of the 6502 second processor, giving additional access to 47K of text storage space thanks to the extra memory available. From Practical Computing, November 1984

The BBC Micro contract is renewed

Also in this month, Acorn signed a new contract with the BBC which secured the micro's production and distribution for another four years.

This was clearly a setback for Clive Sinclair, who had often grumbled about losing out to Acorn on the lucrative contract back in 1981 and who had expressed hopes on several occasions of increasing his share of the education market. Acorn's Chris Curry said of the deal:

"The BBC Micro is, and will remain, the keystone of an expanding system, capable of meeting the needs of a wide range of users. Acorn, in association with the BBC, will be developing the system further to ensure it benefits from future technology, while retaining its unique core of compatibility"[5].

A Research Machine 380Z - 3rd place in the schools micro race - at the Centre for Computing History, CambridgeAccording to a survey published in September 1984's Micro User, 46% of teachers owned a BBC Micro - twice as many as owned the next-most popular Sinclair Spectrum, and of 35,700 schools surveyed, nearly two thirds were planning on buying the Acorn machine during 1984.

Three quarters of schools and 84% of colleges had at least one BBC, with Research Machine's 380Z coming in at 18% with the ZX81 at 16%, whilst the same survey also confirmed a Department of Trade and Industry report which said that 83% of orders under the subsidised "Micros in Primary Schools" scheme were Acorns[6].

No wonder Uncle Clive was still grumbling about it three years later, when he was quoted as saying the whole situation was "outrageous" and that his company was "the most successful company at the time" and that "losing the BBC contract was very damaging"[7].

Sinclair's mistrust was no doubt fuelled by the fact that in the autumn of 1983, John Coll, former teacher from Oundle School near Peterborough and the man "who took the Acorn Proton to fame and fortune as the BBC Micro", left Acorn to become the head of software for the Government's Micro Education Project at the Department for Education and Science.

According to Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World, this would have clearly come across to companies like Sinclair and Research Machines - both with a keen eye on the education market - as some sort of "Fifth Column" movement by Acorn[8].

When the MEP programme came to an end at the end of 1984, Apple made a move on to Acorn's turf by reducing the price of the Apple IIe to just over £400 for school purchasers, which was about the same as the BBC.

However, unlike MEP-discounted BBC Micros, Apple's discount wasn't limited to one machine per school, with Apple publicising its "Our Kids Can't Wait" programme as stepping in where the Government had left off[9].

MEP appeared to be replaced by the very-similarly-named Micro-Electronics Program for Schools, also known as MEP, which ran until 1986.

When this in turn finished, it was replaced by a scheme that tacitly recognised that the hardware - in the era of IBM PC uniformity - had become largely irrelevant and that software was now the thing.

The Software Support Scheme, which had actually launched on the 1st October 1985, operated for three years.

It was intended to enable local education authorities (LEAs) to buy subsidised software in order to "make best use of [their] hardware", thanks to the £3.5 million cash that the DTI was putting up.

The conditions of the scheme required that only "serious" educational software could be bought, and that it couldn't be spent on admin software for schools, nor on anything that wasn't commercially available.

Further requirements included schools having to stump up their own money to match in the second and third year of the scheme, with the overall intention being that the bigger spend from schools would make it worthwhile for companies to invest in the educational software market.

Unsurprisingly, the DTI was claiming that the scheme had been met with "acclaim by the software industry", and that it would go far in helping small companies to enter the serious software market.

However, MP Shirley Williams, once a minister for education in Harold Wilson's cabinet, pointed out that merely encouranging general sales wasn't nearly as useful as funding specific educational software, whilst some software producers were questioning whether £3.5 million, spread over three years and carved up between over 150 LEAs was going to make any difference at all[10].

Back in 1984, Sinclair was also redoubling its efforts to take over Acorn's education market with the delayed release of its QL machine. Uncle Clive reckoned that:

"the time comes for something to be replaced and the BBC machine was an excellent machine in its time. It was designed some years ago and clearly we are able to offer an enormously more powerful machine, so it seems right for a change".

Sinclair's plan to topple Acorn was based on a top-down approach, which Sinclair thought wouldn't be any more difficult than replacing one text-book with another.

Pre-empting Strathclyde University's purchase of 7,000 QLs in the following year[11], Sinclair thought that the QL - even though it sported a slightly-hobbled 68008 processor - would be:

"used pretty swiftly and become a standard in universities. They need the 68000 - they need a much more powerful machine"

Sinclair considered it to be a small step from this to seeing how the QL would grow, encouraged along by the promised hard disk and a series of languages - including, apparently, Unix, which wasn't a language but an operating system. Accordingly:

"once universities have amassed QLs, schools will follow. They are not going to throw the BBC machine [out] overnight, but as they replace them, or buy new machines, they will go for the QL".

This was also apparently manifest because not only would the QL would become some sort of university standard, but it was also "so much better value"[12].

Acorn walks the corridors of power

The Houses of Parliament and Westminster Bridge, LondonElsewhere in government, it was becoming apparent that the BBC Micro might even become the standard computer in Parliament.

As part of an initiative sponsored by Labour MP Dr. Jeremy Bray, the Computer Sub-Committee of the House of Commons Services Committee was investigating various options to provide computer systems to MPs.

It seemed to be coming round to the idea that instead of some behemoth Mainframe installation with terminals, MPs would be better served by having their own micro - as long as all MPs, at least within one particular party, used the same system.

Four fundamental requirements had been identified in a report produced by Bray - the chosen machine should have a large number of established users, have good communications including Prestel, should be cheap and must be capable of running CP/M - which the BBC complied with following the release of Torch's ZEP processor/disk pack or Acorn's own Z80 card.

Perhaps the thing that sealed the deal was tucked away deeper in Dr. Bray's report.

This was the fact that Acorn was willing to do a deal whereby Labour MPs got BBC Micros complete with disc interfaces or a complete package with disc drives at significant discounts, a situation showing that Acorn was nothing if not pragmatic, given managing director Chris Curry's staunch support for Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

There was other support for the initiative amongst MPs, including Redcar MP and former steel-worker Jim Tinn, who it was reported was able to address 400 Christmas cards in 15 minutes thanks to his BBC Micro.

It was also thought that the House of Commons was close to having its own BBC user group, especially as an additional surge of micros was expected with the March 1984 secretarial and office-facilities budget[13].

Russian roulette

When the United States eased its grip on COCOM - the co-ordinating committee controlling trade with Eastern Europe, it became possible to trade with the Soviet Bloc.

Acorn was keen to get a part of the 8-bit Russian market, which was estimated at a potential worth of $180 million US (about £500 million in 2026), and so bunged a somewhat-underwhelming £50,000 at developing a Russian keyboard and getting its manuals translated.

However, as well as competition from Sinclair's ZX81 and Spectrum machines, which had been cleared as being "small" computers and which were thus allowed through the security net, the US was still holding its line that bigger computers were still not allowed as they had military applications, which included the claim that an Apple II could control a Minuteman ICBM.

For this reason the US insisted that such machines could not be sold with any networking ability.

At the same time, Acorn International was on the verge of signing a manufacturing and distribution deal in mainland China[14] whilst in Israel, BBC Micros had been selected to drive the computer graphics used in Israel's 1984 general election, after TV producer Rafi Ginat had toured Europe and the US looking for hardware.

It turned out that the BBC Micro's output could be plugged straight in to the broadcast system thanks to a device that BBC and Acorn engineers had already produced for TV series "Making the most of your micro" at the beginning of 1982[15].

This meant that the BBC-generated pie charts and other graphs fed straight in to the election results programme and broadcast nationwide, plus the whole setup came in about at about a tenth the cost of the nearest competition.

It also helped that Hebrew software was already available as the micro was already widely used in Israeli schools as well as Jewish schools in the UK[16].

Further afield, and inspired by the Queen's visit to India in 1983, which included a gift of 36 BBC Micros in the form of six 6-station Econet systems which was presented to the Indian prime minister Zail Singh, the Overseas Development Association, as part of a British aid programme, followed up in the autumn of 1984 with a further gift of £1.2 million worth of technology to India.

This included 900 BBC Micros with Microvitec monitors, disc drives, printers and software, as well as a few hundred copies of Acorn User magazine, as subscriptions were seen as a useful way of providing remote support.

The micros were expected to be used to contribute towards Indian computer literacy, rather than as teaching aids for other subjects[17].

It was also hoped that a seperate deal struck with the Indian Government could lead to 250,000 BBC Micros appearing in Indian schools by the end of 1990, in what would have been a significant extension to the lifespan of the venerable 1981 micro.

It was intended that the machines would be made locally by the state-owned Semiconductor Complex Limited of Punjab, initially from kits sent over from Acorn, but later from scratch, including second-sourcing the 6502 processor from MOS Technology/Commodore via Rockwell - a move which would have potentially provided Acorn itself with a source of cheaper processors for its own machines.

The only thing that would need to be supplied by Acorn were the custom-made ULA chips, which were manufactured by Ferranti.

The deal was similar to another with Mexican computer company Harry Mazal, which was to produce machines, including custom power supply, television output and keyboard, for the entire South American market[18].

At the time, some 30 countries had already sent over delegations to see how the computer education programme had been set up, with the result, according to Information Technology Minister Kenneth Baker, being that Acorn and the other companies in the school scheme - Sinclair and Research Machines - were selling abroad "in substantial quantities". Baker continued:

"The scheme has undoubtedly been a success and we can rightly boast that we are, in terms of education, the most advanced in the use of computers".

However, the Microcomputers in Schools scheme, which was itself a follow-up to a previous scheme, was due to end in December and the DTI had yet to decide whether further support schemes were necessary[19].

Acorn's US mis-adventure

This all came at a time when the first signs of Acorn's impending financial crisis were showing, heralded by a share slump from the debut price of 120p down to 107p on London's Unlisted Securities Market.

The slump had been triggered following the publishing of Acorn's annual results for its first full year as a public company, which showed only a modest increase in profits of 20% - up from £8.6 million to £10.8 million - despite a doubling of turnover up to £93 million (£390 million in 2026).

The increase in profits was significantly less than the trebling of profits between the two half-year positions the year before[20].

By this time (October 1984) Acorn had shifted 370,000 BBC Micros and 90,000 Electrons but losses caused by the ultimately-doomed attempt to break the US market had stunted overall profits causing Acorn to send over one of its sales bosses - Joe Black - to try and sort things out.

Hermann Hauser however was convinced that the company was on the right track, saying:

"We've a sound foundation in the US and overseas and have established a name and reputation for quality and design".

He was confident that this would pay back in terms of a good share of the US market in "an acceptable timescale".

As part of the expansion, Acorn had invested in the Acorn Research Centre, otherwise known as "Acorn West" - a research building in Palo Alto, on the edge of Silicon Valley.

The venture was connected with Hong Kong turntable manufacturer BSR and was an attempt to produce a small laser disc "essential for the office of the future" according to Chris Curry[21].

The doom in the US contrasted with the first half of the year, where it was reported that Boston-based Acorn Computer Corporation had taken orders worth $50 million, with the Washington District School Board of Phoenix, Arizona, putting in a $175,000 order.

More than 1,000 dealers had been appointed to sell the American version of the BBC Micro[22].

When Acorn launched in the US, it opened a warehouse and an office with a staff of about 40 with the intention of taking 10% of the US education market, which was largely dominated by Apple.

It had even bought the US rights to the BBC's TV series like "Making the most of the micro", as hosted by Ian McNaught-Davis.

However, as an Acorn spokesman later admitted, the company's optimism "wasn't justified and the market impact turned out to be far less than 10%".

This resulted in the trimming of its US staff by 80% which brought it "more in level with its US sales", although that still left "a small office to deal with software support for schools which have taken the BBC".

It was this news of the "down-sizing" that triggered a 14p drop in Acorn's share price, taking it down to 61p - about half what it had been when Acorn first joined the Unlisted Securities Market back in October 1983[23].

Acorn's financial disquiet wasn't preventing its founders from investing in other companies.

In November 1984 it was announced that Chris Curry and Hermann Hauser had each taken a private 20% stake in Meridian, a company already famous for its high-end hi-fi and which had been founded by Allen Boothroyd, the industrial designer of the BBC Micro and an alumnus of Cambridge Consultants Ltd.

One of the unique features of Meridian's well-regarded hi-fi separates was that they could all be interfaced together over a digital link, using Acorn's own Econet network[24].

At about this time, Acorn announced that it was reorganising its Computer Education Service (CES) education arm.

Initially a part of semi-nationalised ICL, CES had been acquired by Acorn in October 1983 for a reported price of less than £100,000.

The six-strong staff of software designers - the actual writing of the software was contracted out - was made up of former teachers and headed up by Dave Roberts[25].

After the buy-out, the staff all transferred from ICL to Acorn's new Maidenhead office, however in July of 1984 Acorn announced that it was moving the staff again from Maidenhead to Cambridge. Chris Curry said of the change:

"Educational software will continue to be the responsibility of CES, but the group will come under the aegis of Acornsoft management. We are going to increase the scale of CES operations and put more people and more money into CES. It must be closer to the body of the company to prevent duplication".

The move wasn't without its critics as CES had built up a good reputation with the schools it had worked with. Howard Curtis, examiner for the Joint Matriculation Board said:

"Schools and advisers are crying out for help and CES is one of the bodies they look to. CES gives Acorn a friendlier face than exists within the rest of the company".

Berkshire-based schools adviser Colin Monson echoed this theme when he stated:

"Our contact with Acorn is through CES, as we have found it difficult to go to Acorn, and [their] dealers know little more than we do"[26].

Acorn's late-1984 attempts to woo the Soviets were snubbed in the summer of 1985 when Russia placed its first major order for micros with the Japanese MSX consortium, paying about £2 million for 10,000 MSX machines.

Acorn International's Joe Black said as COCOM restrictions were close to being finally lifted that:

"While the timing of this order is not surprising, it is a little surprising it went to MSX".

However he continued optimistically:

"This order looks like a short-term contract and I would think there would be a number of short term purchases made for different machines".

Jeff Wakeford of Memotech, a manufacturer of almost-MSX machines that also wanted some of the action in Russia continued:

"The Russians did say they wanted 10,000 machines for this year to get their educational programme going, so this deals means Memotech did not get the initial order. However, they have asked us to go back to the Soviet Union with the Memotech micros in August"[27].

Date created: 23 November 2019

Last updated: 23 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.