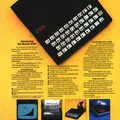

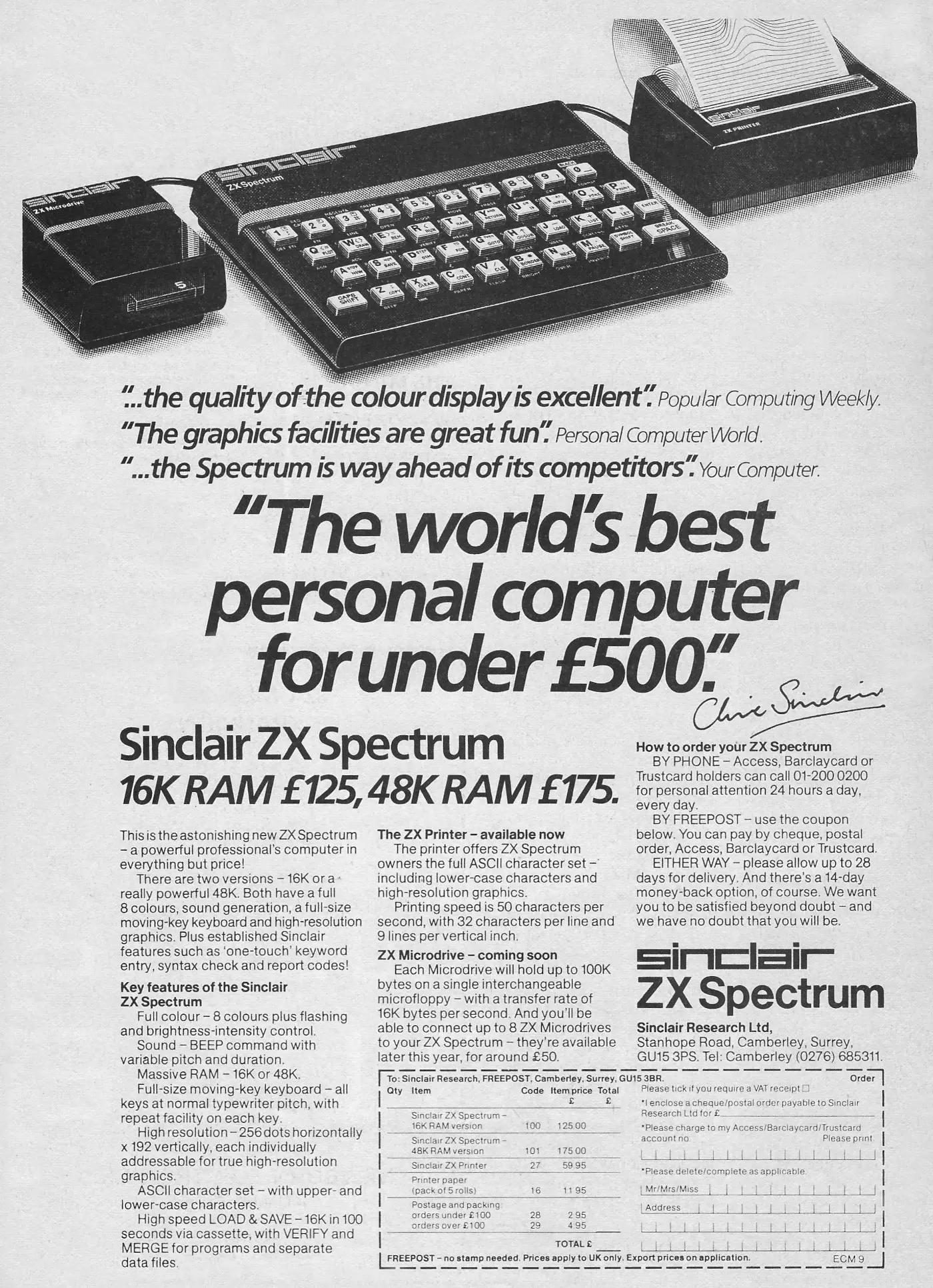

Sinclair Advert - September 1982

From Electronics and Computing

The world's best personal computer for under £500

Sinclair was nothing if not bold with its claims, including this one that the Spectrum - announced just a few months before at a press conference at the Churchill Hotel on Friday, 23rd April 1982 - was the best personal computer in the world for less than £500 (£2,480 in 2026).

This was a fairly wide range at the time which included Acorn's BBC Model B, Atari's 400 and 800 and the Commodore 64 - although that hadn't made it to the UK yet.

At launch, the 48K Spectrum retailed for £175 (£860), which was a breakthrough price for a colour computer with more than a few kilobytes of memory.

And despite its "dead flesh" keyboard, the Spectrum was certainly popular, going on to sell around five million units[1] in its various guises - right up to the Spectrum +3 with integrated floppy drive.

In its September 1982 issue, Electronics and Computing commented on the shape of the microcomputer industry in the UK, showing just how much competition the Spectrum was up against.

A market report revealed that there were some 112 different manufacturers selling micros in the UK, a number made up of 44 from the US, 38 from the UK, 14 from Europe, 12 from Japan and 4 from the rest of the Far East[2].

There was some optimisim that this would mean that the UK computer industry would "stay in the business", unlike the motobike and ship-building industries before it.

Sadly, this position did not last beyond the 1980s, with the exception of Acorn - Sinclair's arch rival.

Meanwhile, there was some confusion in the market between the ZX Spectrum and another Spectrum which had been launched the previous September.

This was perhaps surprising as the "other" Spectrum was produced by specialist company Micro APL and was a 16-bit multi-user multi-tasking machine with an entry-level price of some £10,000 - or £49,600 in 2026 - a mere 57 times more than its erstwhile competition.

Micro APL stated that whilst it had actually been getting enquiries from customers confusing the two machines, there "were no hard feelings" before noting that it hadn't bothered to register the name because it had been advised that the name was too common to be a trademark[3].

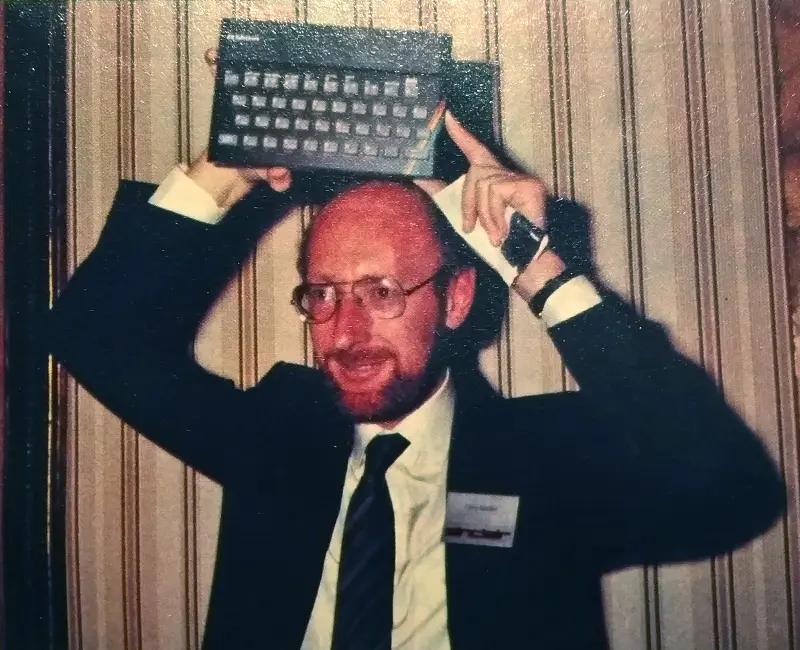

Uncle Clive triumphantly launches the Spectrum. © Sinclair User, 1983At the launch, where Clive was said to have announced the Spectrum's feature set with all the "aplomb of a conjuror pulling live rabbits out of a hat", the normally-cynical collection of assembled journalists apparently applauded, with one of them even ordering a machine on the spot.

However, although the machine had got off to a good start, things started rapidly going wrong, as the promised four week delivery period for orders placed in April rapidly turned into eight to ten weeks.

Orders placed later fared even worse, with months being not unheard of.

By August the lead time was up to 12 weeks, whilst the company came under fire from the Advertising Standards Authority for its continued claim of "28 days delivery" in its advertising.

Delays were being caused by sheer demand as well as circuit-board timing problems, which were discovered just before the first machines were due to be despatched, plus there were continuing problems with the subsequent re-design, as well as high failure rates in production.

Oh, and the Timex factory in Dundee where the machines were being built also closed down for its three-week annual leave in the midst of all the chaos, so by September 1982 only around 25,000 out of 40,000 orders had actually been completed.

None of this however seemed to deter the eco-system surrounding Sinclair, as new independent companies as well as those that had grown up around the ZX80 and ZX81 market were producing a wide range of software and hardware add-ons for the Speccy within two months of its launch[4]

The BBC Contract

An early 1982 mockup of Sinclair's pocket TV, © Practical Computing, August 1982Back in 1981, Sinclair had been one of the companies - alongside Acorn, Tangerine, Research Machines, Transam and Nascom - that had tendered for the BBC's microcomputer project, after the BBC had given up hope of ever seeing a machine produced by its original choice, Newbury.

Oddly enough, Newbury's machine - the NewBrain - had started as a Sinclair Radionics project in 1978, before a change in management at the National Enterprise Board, which had been brought in to help fund Sinclair's Microvision TV project.

The NEB's cash injection meant that Radionics was now essentially part-nationalised, which led to a shift in emphasis away from consumer electronics back to Radionics' old instruments market - largely because the NEB didn't think that Sinclair could hold its own in the electronics market against the perceived threat from the Japanese.

This triggered the exit of Clive in 1979 from the company he had founded, as well as the farming off of the NewBrain to Newbury (and eventually Grundy)[5].

The worry about the Japanese invasion was a common theme amongst government and the UK micro industry, so it was all the more ironic when Sinclair Research signed an agreement with Matsushita towards the end of 1981 to export micros to Japan[6].

One of the reasons that Sinclair didn't get the BBC contract was said to be because of the company's existing success, which had made it unwilling to adapt to the BBC's particular specification - in particular over the requirement for a structured BASIC; expansion, printer and network ports; state-of-the-art colour graphics and sound, and analogue inputs.

This inflexibility left the BBC feeling that it would end up with a "Sinclair machine in BBC colours" and contrasted significantly with Acorn which, as well as being far less secretive, was eager to adapt to the BBC's requirements.

"The BBC makes the best TV programmes - and Sinclair makes the world's best computers!"

As Acorn's Chris Curry put it in a 2008 interview:

"Clive was much less inclined to accept outside input. I mean we were being absolute tarts about it. We were doing just what the BBC wanted us to do and Clive certainly wasn't doing that"[7].

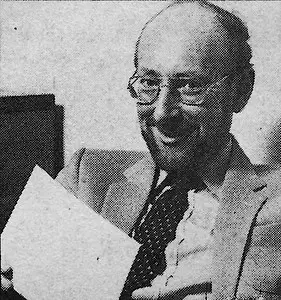

Clive Sinclair in happier times, © Popular Computing Weekly September 1983Clive was still furious about losing out, and got in several digs at the April launch of his might-have-been BBC Micro, which was now known as the ZX Spectrum. Comparing the Spectrum to the Model A BBC Micro, he said:

"It's obvious at a glance that the design of the Spectrum is more elegant. What may not be so obvious is that it also provides more power. [It] has more usable RAM and higher maximum RAM. It offers twice as many colours on the screen at any one time [and] also offers user-definable graphics. It employs a dialect of BASIC already in use in over 400,000 computers worldwide".

The latter comment was a reference to the BBC's decision to insist on its own custom BASIC rather than perhaps use Sinclair's "standard", which Sinclair reckoned was "sheer arrogance" on the BBC's part. He concluded that:

"The BBC makes the best TV programmes - and Sinclair makes the world's best computers!".

Elegant Design

Sinclair's particular obsession about "elegance" cropped up frequently, as it seemed to be a core component of the company belief system and appeared to be almost a shield of righteousness with which to fend off the competition.

Whilst some observers had suggested that elegance was merely a "self-serving concept fitted up to justify under-specification", Sinclair did seem to have considered it in the design of the Spectrum, which was apparently not just small simply in order to make it cheaper. He said:

"If you made [the Spectrum] any larger it would simply be more expensive. There would be no contra-benefit, so elegant design has led to a very compact shape compared with its competitors, not just because we wanted it to be tiny. If we wanted to make it really tiny we could have made it, I suppose, the size of a cigarette packet, but that would not have been functional, because the keyboard would not have been usable".

Continuing with the keyboard, which was one of the few areas in the Spectrum's design that Uncle Clive took a direct interest in, Sinclair suggested that:

"The Spectrum sacrifices nothing to size. The keyboard is exactly the same spacing and pitch as the IBM, which is why we went for that size. If we went down to the the size of a cigarette packet it would not be cheaper, it would be more expensive. That size is optimum"[8].

Meanwhile, Sinclair was not so much mad at Acorn but at what he saw as the BBC's arrogance in trying to set a new language standard, and even in making micros at all, suggesting that it was about as acceptable as a BBC car or BBC toothpaste.

In an extensive interview in July 1982's Practical Computing, he railed

"They were able to get away with making computers because none of us had sufficient power or pull with the Government to put over just what a damaging action that was. They had the unmitigated gall to think that they could set a standard - the BBC language. It is just sheer arrogance on their part".

Perhaps trading arrogance with arrogance, or at least a fair degree of hubris, Sinclair continued:

"We will win hands down because we know so much better what is needed and know so much better how to do it than the BBC does that our system, our machine and our language will completely win out in any competitive battle"[9].

Sinclair rolls its own BASIC

Whilst many companies of the day would pick an off-the-shelf BASIC such as Microsoft's, Sinclair went off and wrote its own for its first machine - the ZX80.

This was not only because of Clive's wish to create a "radically new BASIC interpreter" for the ZX80, but for the more prosaic reason that it was unlikely that a standard BASIC would fit into the tiny 4K of ROM that was available.

What Sinclair ended up with was a highly-compact, very structured (internally, if not in the programming sense) and almost totally bug-free integer-BASIC interpreter with just enough additional minimalist functions to manage the keyboard, display and cassette interface.

This well-regarded 4K program was re-written and extended into 8K for the ZX81, and included some extra routines such as the infamous slow/fast handler, a floating-point calculator and some more - but still rudimentary - cassette handlers.

However, after all this extra stuff was added, it was found that there wasn't enough room and so some functions had to be removed and others re-written to be more economical, even if in some cases it meant they would run slower.

It was also said that this version of the ROM looked like it had been written in a hurry as it featured several significant bugs, including one which gave the answer to 0.25**2 (the square of 0.25) as 3.1423844, when it should be 0.0625.

The faulty version was shipped on around 100,000 ZX81s, whilst 20,000 later ZX81s were shipped with a hardware add-on to fix the maths bugs in the summer of 1981.

The situation was clearly not ideal and Sinclair had the 8K ROM completely re-written, with around 400,000 of the updated machines shipping during 1982.

When the Spectrum eventually shipped in 1982, its 16K ROM apparently contained large chunks of un-modified code from the ZX81, complete with many of its bugs.

Sinclair User lamented that "the tidiness of the first [ZX80 4K] program is now almost completely lost and the present 16K program has only a token attempt at structure".

However, it also suggested that - at the time when Sinclair's micros had sold more than pretty much anything else - it was also perhaps the most successful machine-code program ever written[10].

This success was perhaps despite the fact that the early compromises made to make Sinclair BASIC work on the ZX80 and '81 lived on into the Spectrum, making it significantly slower than much of its competition, including the BBC Micro and even the memory-starved VIC-20.

Nigel Searle goes to school

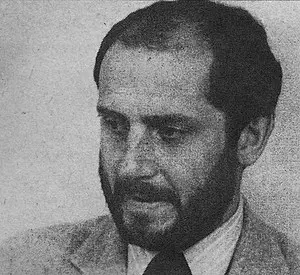

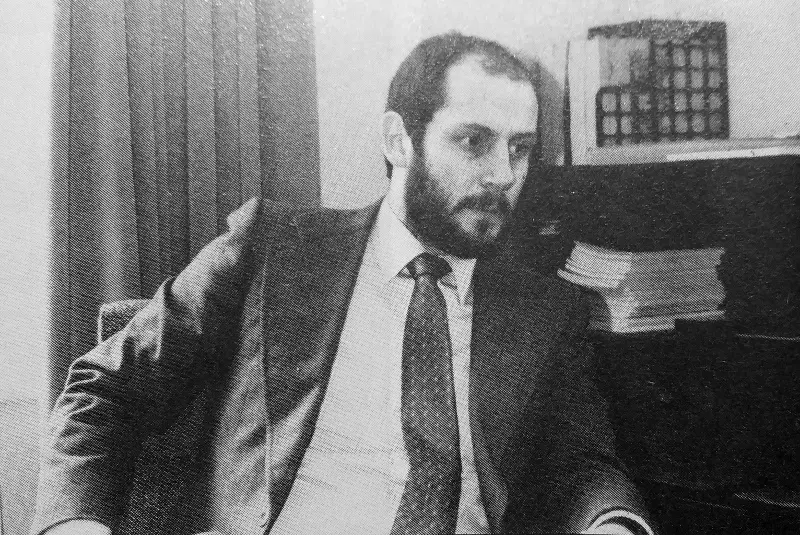

Nigel Searle of Sinclair, © Popular Computing Weekly September 1983Back in the summer of 1982, Sinclair got a crumb of comfort when the Department of Industry (DoI) was persuaded to accept the Spectrum as an alternative to the BBC Micro in the £9 million "Micros in Primaries" scheme.

The deal to include the Speccy had been largely brokered by Nigel Searle, a long-time Sinclair trustee who had ended up as Sinclair Research's managing director.

On his return to the UK from a trip to the US, he had picked up rumours of the primary-school scheme and got the DoI to add the Spectrum to its list, even though it had already chosen the micros it wanted for the scheme.

Definitely excluded was Commodore, largely on account of its non-British North-American-ness, which reacted by reducing the price of its PETs by between 20 and 33%, for a three-month period commencing in September[11].

Nigel Searle of Sinclair, © Sinclair User 1982Searle had first joined Sinclair in 1972 during the Radionics days, where he had been designing pocket calculators.

He then moved to California and then New York, were he looked after the promotion of Sinclair's calculators and watches in the US market.

He left the company when the National Enterprise Board came along, saying that "The calculator business was not doing too well and also it was not really the same company once the NEB was involved".

Not long after Clive started Sinclair Research and had launched the ZX80, Searle rejoined to run the US office in Boston, selling the '80 and '81, before moving back to the UK to head up the computer division of Sinclair Research.

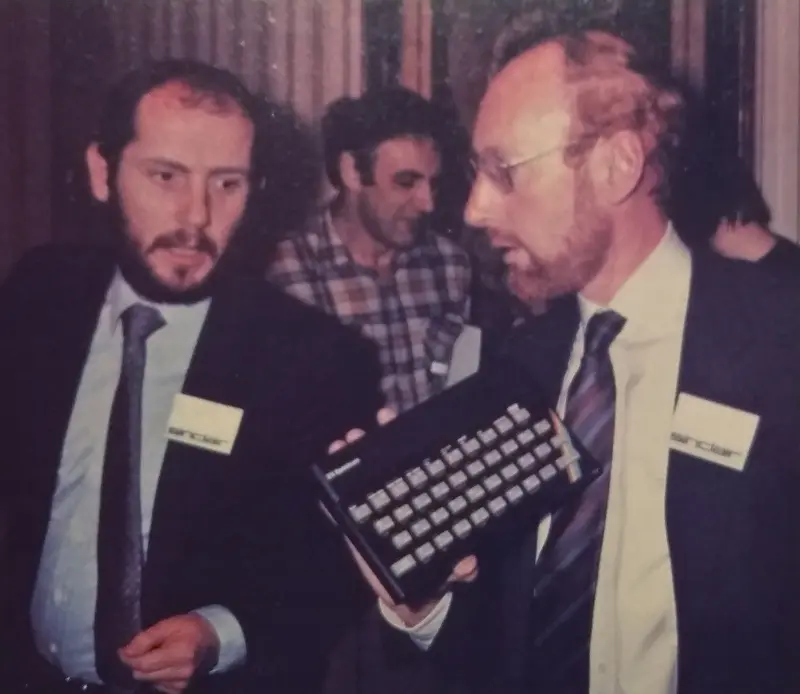

Nigel Searle with Clive Sinclair, who's waving a Spectrum around at the Spectrum's launch event at the Churchill Hotel, © Sinclair User 1983In an interview with Sinclair User, which appeared in the 1983's "The First Sinclair User Annual", Searle explained Sinclair's approach to selling its computers, which up to that point had been almost entirely mail order, even when the Spectrum had launched.

"There are no plans at present for putting the new [Spectrum] machine into WH Smith, which is Sinclair's only retailer".

He suggested that the reason for this approach was that "not many others are selling so many computers as we are" and that "we have sold far more computers by mail order than anyone who has sold through stores".

Sinclair's attachment to mail order was also explained by the fact that when the company started, there actually wasn't any obvious retail outlet for its new micros.

Searle stated "It did not occur to me, or anybody else, that Boots, Curry's or Rumbelow's would sell a computer".

Plus, there was also the unavoidable fact of economics that not selling through retailers meant higher profit margins. Or as Searle put it, when you sell through mail order, you "do not have to give a discount to retailers which you normally have to do" - a situation which could add up to 50% to the retail price.

Instead, Sinclair had no pre-determined limit to its advertising budget and would spend "as much on advertising as will produce a profitable number of sales".

This led to a spend of some £5 million in 1982, rising to a forecast for 1982 of more than £10 million[12].

It was certainly a profligate advertiser, and frequently published its glossy 4-page (or more) gate-fold "mini magazines" in popular computer magazines of the day.

Sinclair's crack at the BBC wasn't particularly successful, as the company was essentially shunned by the Local Education Authorities responsible for deciding which micros their schools bought.

This was not just because of the perceived toy-like properties of the Spectrum when compared to the all-metal case and proper keyboard of the BBC Micro, or RM's similarly-robust 380Z, but was also largely because many authorities were having to retain compatibility with the computers they had already installed in their secondary schools during the previous scheme, and of course Sinclair hadn't been an approved choice before.

By November 1982, some four months after MIP launched, only three out of 422 applications under the scheme had been for the ZX Spectrum[13].

Online software

In non-Spectrum news, it turned out that Searle was a fan of Prestel, the dial-up Viewdata system that had been launched by state monopoly the GPO in 1979. He thought it too expensive, but did offer the prediction:

"You have to consider not what benefit people get from [Prestel] now, but what they will get in the future. Kids will do more of their learning from computers and many people will work from home".

Sinclair had made some moves to support Prestel as it announced it was developing a Prestel adapter which was planned to cost "substantially less than £100", according to Searle.

That compared favourably to the winner of the British Telecom ZX81 Prestel Adapter competition, Martochoice Ltd, which was expecting to charge between £120 to £150 (£740 in 2026) for its adapter.

Searle remained convinced that the ability to download software, which provided the benefit of constantly updated software and less need to store everything, was crucial, suggesting that "the future of personal computing lies in communication"[14].

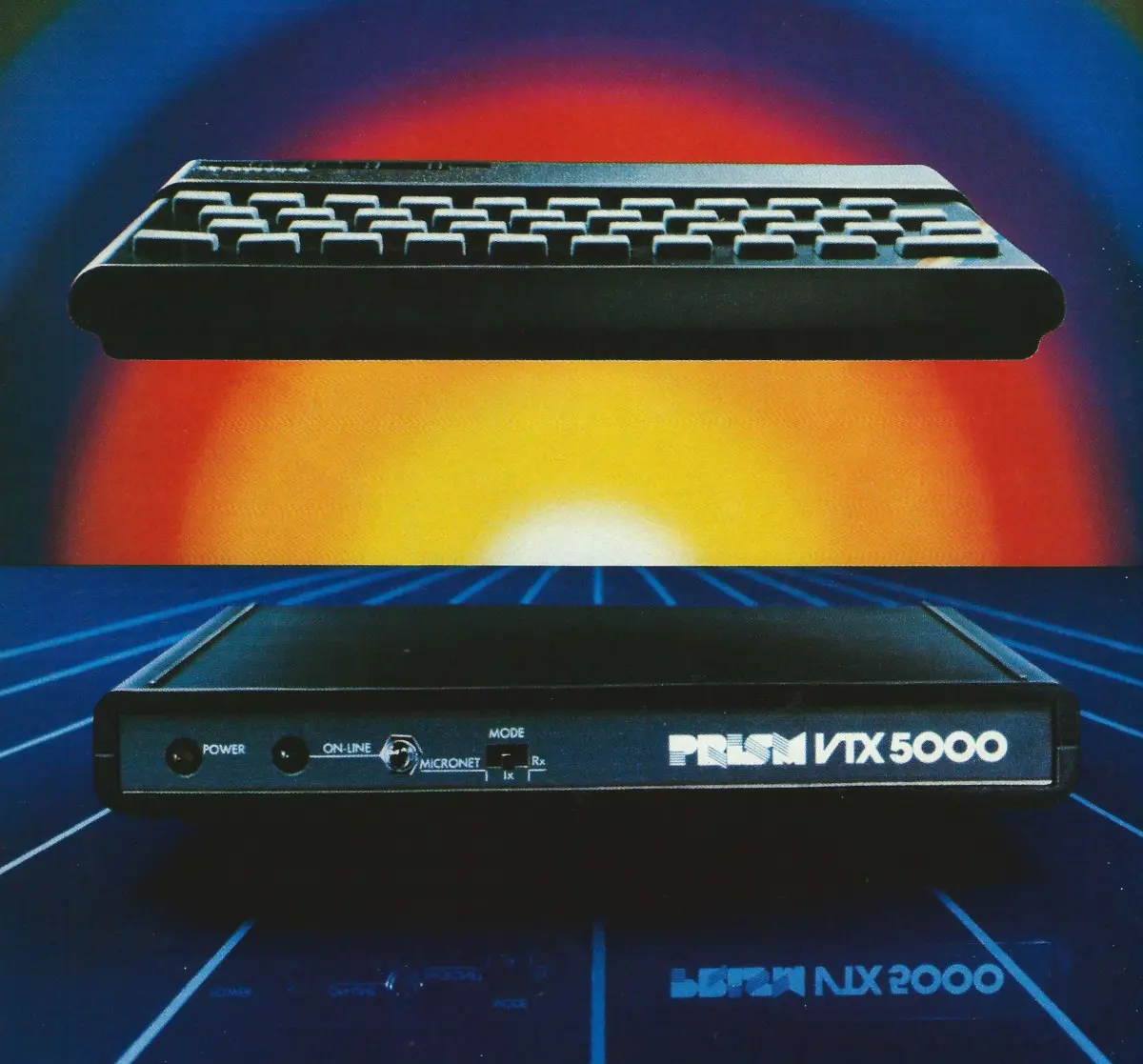

Prism's VTX 5000 Prestel/Micronet adapter, from Personal Computer News, 1st September 1983

Searle went on to explain Sinclair's wider move into software, which he had admitted was something that the company had neglected in the past[15], by pointing out that as machines were becoming more complex, they were becoming more useless without it.

It was also clear that there was much profit to be had in software, as its value was in its content and not in its physical form.

At the same time, Sinclair was also moving away from its early mail-order setup and exclusive arrangement with WH Smith as everyone else was now selling micros and they had become an accepted part of the High Street.

The transition to retail would however be easier as the company now had a number of outlets it had built up with the ZX81. Searle continued

"Sinclair Research is changing. It had always been a technology-driven company with no great emphasis laid on exploiting the market. We will now sell not just by the most profitable route but by any route that is sufficiently profitable"[16].

The arrival of the Spectrum certainly shook the market up, not least for Commodore, where the 48K Spectrum at £175 (£860 in 2026) was cheaper than the £199 3.5K VIC-20.

Respected PET and VIC software author and writer Nick Hampshire concluded in the first published review of the machine, in May 1982's Popular Computing Weekly, that despite finding the keyboard's cramped layout and red-on-grey text hard going, the "new computer from Sinclair clearly represents excellent value for money and will, no doubt, prove a great success"[17].

Somewhat unexpectedly, the 1977-designed PET was still around even in 1982 and was still seeing ongoing usage in schools and offices[18].

Date created: 05 August 2014

Last updated: 01 February 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.