Acorn Advert - January 1988

From Personal Computer World

Archimedes: 1987 Microcomputer of the year

Acorn's Archimedes - also known in at least some parts of the press as the ARM[1] - had been launched in 1987 and first started shipping to dealers in early Autumn. Acorn's Stephanie Newman noted that:

"[Acorn has] our dealer network and we have a number of retailers in the high street, who will be getting machines around the middle of September".

There had been some concern that the first machines released might still have their operating system supplied on disc - a sure sign that development was not yet complete - but this was also discounted, as Acorn confirmed that the OS would be shipping on actual ROM[2].

The Archimedes was officially launched in the week of the 19th June 1987, along with an Acorn claim that the four mips ARM RISC machines were the fastest microcomputers in the world.

Hyperbole aside, the Archimedes did achieve the significant milestone of being the first commercially-available RISC-based machine ever.

The idea for the RISC - Reduced Instruction Set Computing - architecture was first developed by John Cocke at IBM's Research Centre whilst he was looking into developing fast controllers for telephone switching systems.

The initial ideas were then developed at the University of Berkeley in California, and it was here that the name "RISC" was first coined.

The idea was the perfect antidote to the increasing complexity of mainstream chips, which since Intel's 4004 were becoming faster and larger, but also more complex.

Intel in particular was saddled with backwards compatibility - as each chip added new features and instructions, it also had to retain support for all the instructions that went before.

The entire architecture of Complex Instruction Set Computing became obvious example of Pareto's Law in action - 20% of the instructions accounted for 80% of operations.

Many in the trade had complained about Intel's x86 architecture, but Acorn's Hermann Hauser was particularly scathing, saying in an interview published in May 1993's Personal Computer World that:

"If you actually look at the Intel processor architectures before the Pentium - the 286, 386 and 486 - they're some of the worst that have ever been around in the history of the industry. If you ask an academic or anybody who understands anything about microprocessors, they just happen to be incredibly successful because IBM made it a standard"

RISC architecture was a chance to re-think this design by instead only supporting a small set of instructions, all of which were the same size and structure and which all executed in a single cycle.

Programs would generally be about 30% longer, as complex instructions needed to be assembled from many smaller ones, but the payback was that the running program would require only about a fifth the number of clock cycles, and so would run much faster[3].

Another advert for the Archimedes, mentioning the option of a PC emulator to run MS-DOS software, and the new tag-line "A British Broadcasting Corporation Microcomputer". From Acorn User, May 1988

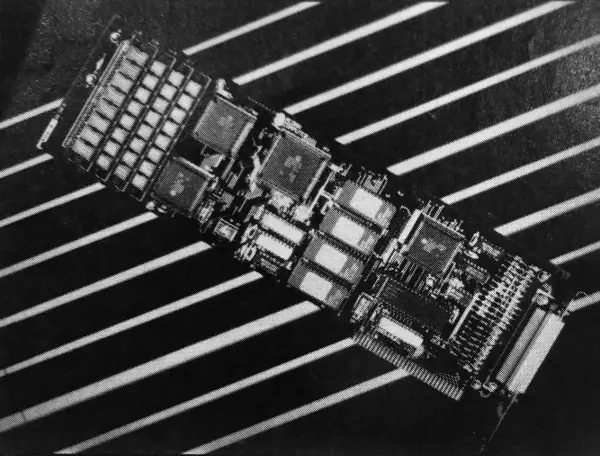

Acorn's RISC processor, the ARM, had been developed by the same team of Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson which had created Acorn's first ever product, the System 1, and much like the earlier board worked well enough the first time it was run, with further debugging done using the system itself.

The first version had 30,000 transistors on it, which according to Hauser was about the same as the Z80 or the 6502 that Acorn used in the BBC Micro. The difference was that it ran about twenty times faster.

Hauser also recounted one of the later versions of the ARM, which:

"Had the performance of a 486, consumed one twentieth of the power, had a million transistors instead of 300,000 [and took up] one third of the space[4]".

Acorn's Archimedes was provided in two ranges - the 400 series having more memory and more expansion, whilst the 300 series was cheaper with fewer options.

The 300-series machine was swiftly adopted as the official micro of the BBC, replacing the previous BBC Master and Master Compact, with which it retained compatibility, at least, as Acorn managing director Brian Long pointed out, for "legal" software, thanks to its Version 5 BBC BASIC.

Compatibility also included the new operating system - known as Arthur - which Acorn suggested would give "a high degree of familiarity to users with BBC Micro experience".

The BBC's endorsement of the machine might have seemed surprising as even the 300 series wasn't exactly affordable, weighing in at £940 for the no-monitor 512K model with a 3½" floppy - that's around £3,560 in 2026.

Also launched was a PC card known as SpringBoard, which provided the same ARM chip which could run machine code software at four times the speed of a DEC VAX 11/750 minicomputer.

Perhaps surprisingly, Acorn itself didn't expect its ARM chips to have a lifetime much more than 10 to 14 years, according to managing director Brian Long, although he wouldn't be drawn on actual sales targets[5].

Nearly forty years and countless billions of shipments later, ARM chips are still very much in existence, shipping in more than 90% of all mobile phones produced[6].

Acorn's legendary pricing and the Dawn of ARM

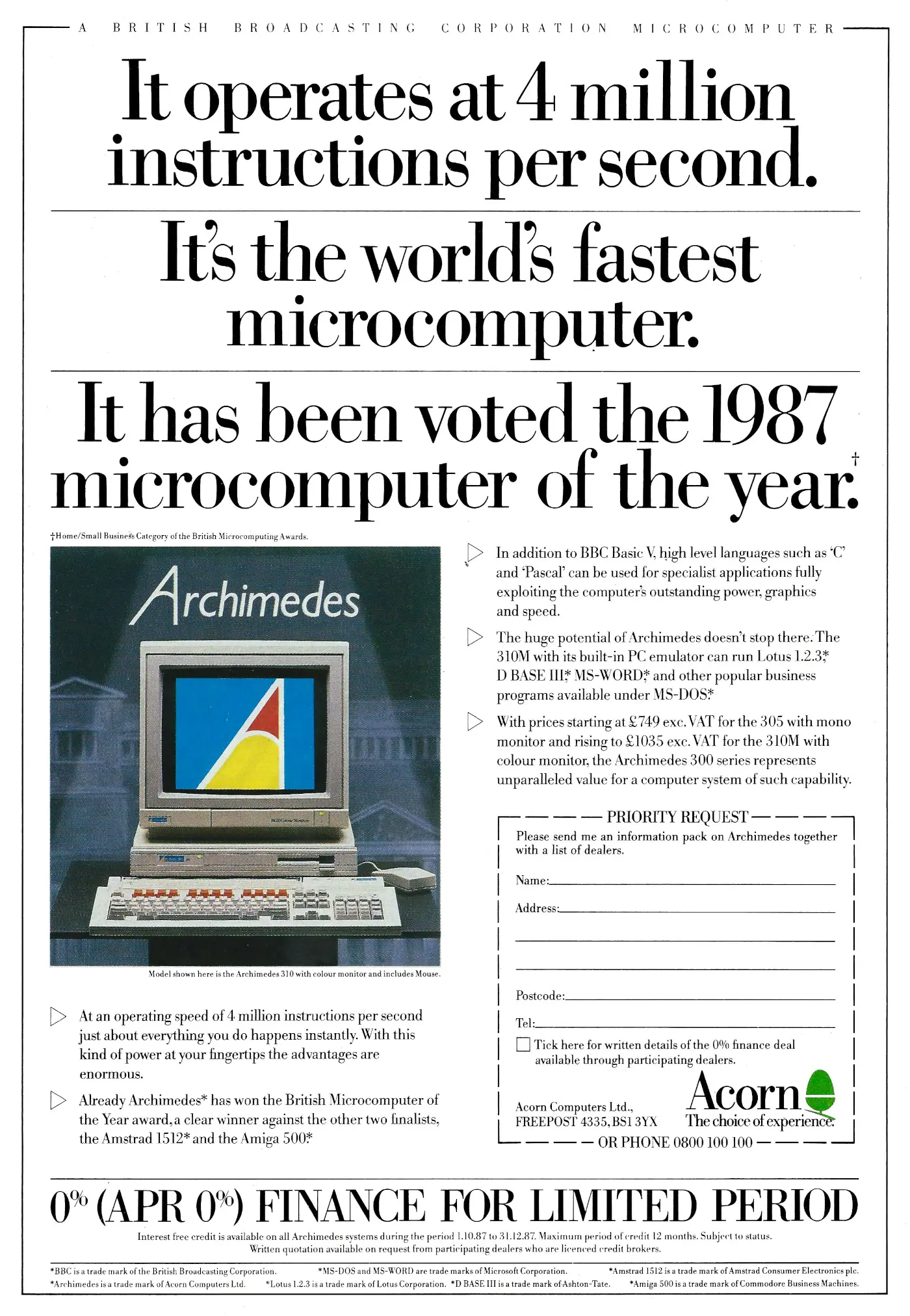

An ARM processor acting as a local printer controller, © Personal Computer World August 1988At the time of its release the Archimedes had been slated by some critics as "another overpriced Acorn product cynically underpinned by the authority of the BBC name".

Your Computer vigorously disagreed, citing the first Archimedes' 90-times increase in processing power over the BBC Master and the fact that it even outperformed both 68000 and 80386 machines whilst being radically cheaper[7].

Even though the processor might have been cheaper, a fully-specced A440 with 20MB hard disc, 4MB RAM and software still managed to weigh in at £2,644, or around £10,000 in 2026 money[8].

The Archimedes was the first machine to use Acorn's own Acorn RISC Machine chip, or ARM processor but, according to Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World in rumours reported in 1987 and rigorously denied by Acorn, it might not have happened if supposed plans by Olivetti to close down Acorn and run ARM itself had come to pass[9].

Acorn's original RISC CPU, containing 25,000 logic gates. The larger area to the bottom left is the chip's registers. The layout was optimised around this as most activity on a RISC chip is based on register transfers. From Practical Computing, October 1986

Luckily for Acorn, Olivetti continued with the project, and by 1988 the processor was, like the Inmos Transputer, being used in things other than high-end micros, on account of its low cost.

One such use included plug in cards cards to control a laser printer, which at the time were often hobbled by the slow speed of the computers attached to them.

However, the ARM processor, plus three more custom chips that Acorn had designed to go with it, were more than up to the task of generating graphics output for even the fastest laser printer.

They were reasonably popular, and even though complexity of set-up meant that Acorn wouldn't sell them to consumers, the company still managed to shift £500,000-worth of the things by the middle of summer[10].

"cheap PC clones were starting to make an impact, so Acorn needed to do something"

The Archimedes was also important for Acorn because the company had so far mostly been relying on its educational market, were there was a tradition of resistance to radical technological change and so where its 8-bit BBC Micro - in various revised forms - was still doing some business.

However, the rest of the industry had by this time left Acorn far behind, with the rest of the world on 16-bit or even 32-bit technology, such as Intel's 80386 or the quasi-32-bitness of the 68000.

Not only that, but in its native market cheap PC clones were starting to make an impact, so Acorn needed to do something.

Whilst launching anything that wasn't an IBM clone was risky, the Archimedes had a significant advantage in that it could still run much of the existing BBC Micro software that schools were using, plus it still had the BBC name attached to it.

It also had the advantage that it was also genuinely speedy, coming in at nearly four times faster than the Compaq 386 in integer and floating-point maths and ten times faster than an Atari ST at string handling[11].

A disadvantage was that, as Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World pointed out, "most programmers know the languages of Intel and Motorola, [but] relatively few can play with the likes of Sun Sparq, or the Transputer, or the ARM"[12].

A Domesday LaserDisc setup, running on a BBC Master, at the Centre for Computing History, Cambridge Not that Acorn's education market was completely dead, as in 1988 Acorn was still managing to secure the odd deal like the one with the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which took 40 BBC Master 128s as part of a system to teach English to diplomats.

The £40,000 deal had come about after the Ministry had been impressed with the Acorn language teaching system in use at the British Council, and was won against international competition. Acorn's Michael Page said of the deal that:

"To sell British technology in what is regarded as the major centre of hi-tech expertise and development is, in itself, a significant coup. It is an optimistic sign that Japan could once more become a lucrative export market for UK manufacturers, following [Japan's] recent trade differences with European companies[13].

The deal also included an information system about the UK, based upon the famous Domesday laserdisc archive project, launched in 1984.

Mixed fortunes

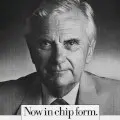

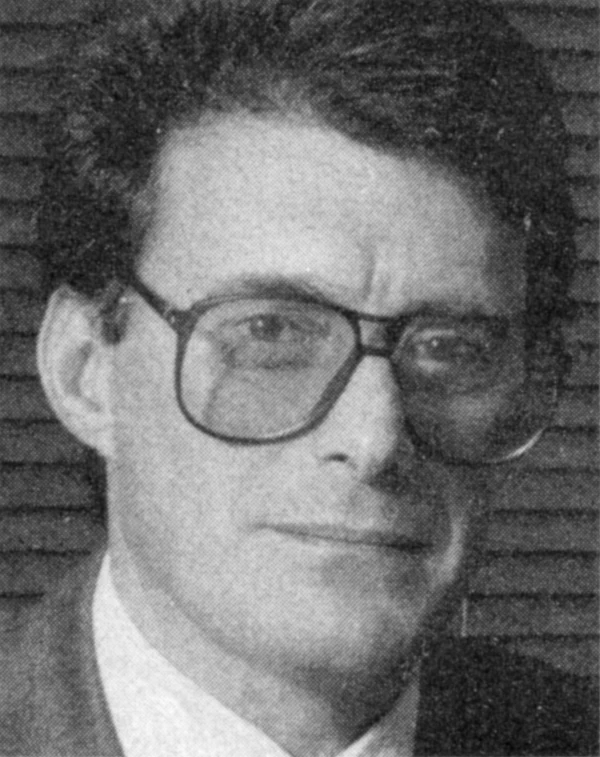

New managing director Harvey Coleman, from Acorn User, May 19881988 was if nothing else something of a year of mixed fortunes for Acorn and the Archie.

Sales had slipped from £46 million the year before to only £36 million, and profits had turned into a loss of £3.3 million, partly due to the expense of developing the RISC chip that the company's future perhaps depended upon.

However, that future had been guaranteed by Olivetti in a message sent to the secretary of state for education, Kenneth Baker[14], in order to allay fears about the company's long-term prospects.

Previous managing director Brian Long had also gone, to be replaced by Harvey Coleman, who said of the company's situation that:

"We've had some significant financial problems in the past but it has become clear that Olivetti's support for Acorn is a continuing element. They consider it a very important mission as part of their group".

The sales of the Archie weren't brilliant when compared to competitor machines, but Acorn had still managed to shift around 5,000 machines in the first three months of its life, and seemed to be heading for the magic 5,000 per month - a reasonable feat given that it was still hard to get hold of one.

There was also a morale boost when Sanyo announced that it was to build an ARM chip set, in a definite sign that the machine was getting some international recognition and perhaps a bit of traction.

Sanyo's licence from VLSI of California - the ARM's OEM manufacturer - had "no strings attached", so it could do what it liked with the chips it built, at a time when it seemed quite a few peripheral manufacturers were picking up the ARM chip for its very high speed and low cost.

There was also some movement in software, which was just as well as there was currently very little available.

Autodesk, authors of the high-end graphical AutoCAD system, was apparently so impressed with Acorn's C compiler that it had started converting all its applications for Acorn's machine[15].

The Archie reviewed well, with Kenn Garroch of Popular Computing Weekly suggesting that "[the Archimedes] is the most amazing micro I have ever used as far as speed goes" and that it was "faster than either the Mac or the ST and provides more windows and in colour".

Garroch's mostly-positive review concluded that

"As soon as I can afford it, I will buy one. Having had a BBC Model A micro as my first machine and then upgraded to STs and Macintoshes, the Archimedes is a dream come true"[16].

Even when Commodore dropped the price of its Amiga 500 to around £400, roughly the same as the Atari ST, Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World reckoned that potential buyers should check the Archimedes out first, suggesting:

"you may find many reasons not to buy an Archie, but you really don't want to see one for the first time after spending your cash on something else"[17].

Acorn's co-founder Hermann Hauser said of RISC machines, in something of a mangled metaphor of the kind he was portrayed as doing in the 2009 BBC film Micro Men[18], that they had an impact that was "similar to what happened in the aircraft industry" when jet engines arrived.

He also suggested that RISC chips "suck the power from the memory and blow it out at a speed that is unrivalled", before offering a put-down of IBM's newly-released PS/2 system as "a beautiful example of the previous design of computer".

The business model that would come to define ARM - that of selling the design and letting OEMs build the silicon - was set very early, as it was seen as a way of getting a quicker return on the significant investment that parent company Olivetti had made in Acorn's RISC R&D.

Acorn's Brian Long suggesting that he would like to see "up to 30%" share of the RISC market taken up by OEMs, and that the company was "already talking to OEM customers in both existing and new market areas and the depth of interest is very encouranging".

Whilst commentators like Robin Bradbeer foresaw a split in the market between the dominant, standard operating systems and "manufacturers who go their own way", Acorn's engineers were certainly doing their bit to make RISC desirable, with Long claiming that Acorn researchers were now running experimental RISC processors at 18 million instuctions per second.

That was over four time faster than Acorn's own Archimedes which itself was already 90 times faster than a BBC Master and even faster - and cheaper - than the state-of-the-art 68000 CISC processor. Bradbeer concluded:

"As far as Acorn has got it at the moment, for the education market and very specialist users, CAD, etc, [RISC] is the way to go.

Acorn eventually fizzled out in 1999, when the company was finally split into ARM, with the remainder going into a new company called Element 14.

Co-founder Hermann Hauser speculated that the company had not done enough to sell itself around the world or even talk to other companies, nor did it try to establish itself as an industry standard.

It had even refused an offer from Commodore to licence its Econet networking technology, at a time when it could have established it as a standard and when it was desperate to get into the US - a move which eventually caused its partial collapse in 1985 and which helped lead to its effective buy-out by Olivetti.

Stan Boland, who oversaw the break up of the company summed it all up saying:

"Acorn had unreal ideas of how business was done. It had no real model of how it was going to earn money. It had a larder full of amazing technologies that were not being sold. It was engaged in ‘Martini’ marketing. It would do anything, anytime, any place for anyone. It had no focus. The breakthrough for any company is when you achieve leadership in your particular space[19]"

Element 14 was eventually bought out by US chip-design company Broadcom in early 2001. In a neat bit of circular reference, the Raspberry Pi Foundation was founded by former Broadcom engineers, and the Pi - which uses Broadcom chips - was very much influenced by the legacy of the BBC Micro, right down to its choice of Model A and Model B product names.

Date created: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 08 February 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.