Acorn Advert - August 1989

From The Micro User

The Archimedes A3000

The A3000 was an update of the original Archimedes - also known in at least some parts of the press as the ARM[1], or more simply the Arc - which had been launched in 1987 and which first started shipping to dealers in early Autumn.

The A3000 shipped with an 8MHz ARM2 with 1MB of RAM and ran new operating system - RISC OS - which replaced the previous "Arthur" OS of the original Archimedes.

It also shipped with a PC Emulator that was capable of running around 90% of the main MS-DOS software of the day, including MS Word, the legendary Word Perfect, Lotus 1-2-3 and Ashton-Tate's dBase III.

It was built more in the style of the original BBC Micro, or in particular the earlier Commodore Amiga and Atari ST, as an all-in-one, rather than the stand-alone box style of the other Archimedes models. It retailed for £1,000 - about £3,350 in 2025.

Although the advert suggests that the A3000 was ideal in the home, Acorn had mostly abandoned the domestic market in favour of education - its previous stronghold thanks to the BBC's Computer Literacy Project and various Micros into Schools schemes in the early 1980s.

Unfortunately for Acorn, education - like business - was very much moving towards the IBM PC, or rather clones of it, as budgets wouldn't really stretch to the real thing when it was often twice the price.

Martin Breffit of Opus (right) shakes hands with Andy Roberts of Skegness Grammar, the first school to opt out of Local Authority control. © Popular Computing Weekly 2nd March 1989One of the clone companies that was challenging Acorn in its education market was Opus, a fellow British firm which was at the time one of the country's leading PC suppliers.

Opus was very much taking advantage of the Education Act of 1988, which introduced "market capitalism", competition for funding and, crucially for micro companies, the chance for schools to opt out of local authority control and its restrictive purchasing guidelines.

Opus considered itself "well ingrained in the higher education and university market", and made the most of it when it signed a sponsorship deal with Skegness Grammar School - the first to opt out - which gave the school a new computer centre equipped with a total of twelve of its 286-based PC IV's.

Worryingly for Acorn, whilst its Archimedes could run BBC Basic software, which was still clearly widely used in schools, so too could Opus's machines, thanks to software supplied by M-Tec Ltd[2].

Other companies were also adding to the pressure as they piled in to the education market with renewed vigor, such as Commodore, which was punting its PC20 plus some DTP software for £800, or around £2,680 in 2025, to NUS members who were using the Midland Bank's "Futures Loan" financing scheme, which meant they would get favourable interest rates on computer-equipment purchases whilst still at college[3].

"We knew that the computer would be well-received, particularly by schools"

Despite the competition, and even though the A3000 was initially perceived as "not setting the world on fire", Acorn was bullish about its new model after a spate of 3,000 orders, including a large one from Durham Local Education Authority, in the first week of unofficial launch.

Acorn's managing director of the week, Harvey Coleman, said:

"We knew that the computer would be well-received, particularly by schools. The influx of orders so soon after launch is very encouraging"[4].

Margaret Thatcher with the UK general manager of IBM, © Personal Computer World June 1988This was no-doubt helped by the huge legacy that Acorn had built up in schools since the days of the BBC Micro, launched in 1981.

Acorn was also ensuring that developers would remain interested in the machine, by releasing of a range of Archimedes programming languages.

These included two versions of ANSI C, Fortran 77 and Pascal compilers, and an Archimedes assembler, which offered direct access to the ARM instruction set, for £228[5] (about £760 in 2025).

At around the same time, it was announced that Acorn's performance for 1988 was significantly better than the previous year, with turnover up from £36 million to £39.2 million - a "respectable, if not remarkable, 8.5% increase", according to Acorn User.

As Acorn's Custom Systems Division, which included Torch and its Communicator, had been shut down in 1987, the mainstream computer division had shown an even better improvement of 16% in its turnover. This had been helped by the relative success of the Master series - the replacement for the BBC Micro - which celebrated its 200,000th shipment in early 1989.

The figures also showed that over 50% of Acorn's business was still in education, with a recent Times Educational Supplement report showing that 62% of all computers sold into education were from Acorn.

Profits were also up, from a loss of nearly £2.25 million in 1987 to around £7.1 million (about £23 million in 2025) "net cash inflow". This allowed the company to pay of its £3 million overdraft, stash £2.5 million away and still have £1.6 million left as actual profit[6].

Micros in schools: misguided?

Research Machines Limited, like its fellow "token competition" compatriot in the BBC Micro contract gig - Sinclair - had something of a hissy-fit in 1987 when the BBC announced that it was to continue giving its name to Acorn products, this time to the Archimedes.

RM's particular beef was that it was "unfair for a state corporation such as the BBC to favour one company over all others", such as it would be equally unfair for the BBC to, say, favour only one brand of television or VCR. As Your Computer pointed out:

"the seal of the BBC on Acorn machines gives it an authority in this field which any other company would find hard to compete with, since much computer education is disseminated using BBC programmes and materials".

Another complaint levelled at the BBC was that it was endorsing:

"an alternative system to MS-DOS, thus differing from the chosen language of the business community and the system used in education in the rest of the world"

This was partly bogus as MS-DOS wasn't actually a language and in some ways the choice of OS was largely irrelevant, as any software could be made available on pretty much any platform if the developers could actually be arsed.

The BBC's Ian Duncan responded that the BBC's literacy project had been using BBC BASIC since 1982 and that it was virtually the standard language in education.

With what might be considered a fairly poor forecast of the future, he continued by saying that "MS-DOS will not necessarily be the computer lingua-franca in the business community in ten years" whilst pointing out that public criticism by newly-formed industry umbrella group British Microcomputer Federation was perhaps less-than impartial given that its chairman was a David Fraser from Microsoft.

In any case, as Duncan continued, the endorsment was from BBC Enterprises, which was a commercial undertaking and therefore not subject to the constraints put upon the parent company.

The new four-year agreement between Acorn and the BBC looked set for continued controversy[7], although Peter Worlock, writing in Popular Computing Weekly, also suggested that if nothing else the row was performing a valuable service as it was opening up a new debate about the use of computers in education.

Worlock continued by re-iterating the question that had been rattling around unanswered since the BBC first plunged into its Computer Literacy project: what was the point of putting computers into schools?

The received wisdom seemed to be that having a computer in every school was a Good Thing and that one computer was better than none - a suggestion that never seemed to have been fully proved, given the diversion of spending from more teachers, books or school trips.

Whilst the extra funding offered during the summer of 1987, which totalled £28 million, might have paid for 55,000 Atari STs or 28,000 Archimedes, it would also have paid for perhaps two million additional textbooks.

It was also pointed out that whilst the BBC was claiming that BBC BASIC was now an educational standard and that it would be "unthinkable" to abandon it now, the broadcaster had still failed to offer versions of the language for any other micro or operating system - although Clive Sinclair would release his Z88 portable the following year which ran BBC BASIC.

Approval will further impact adversely on computer education in both curriculum planning and long-term relevance to national and industrial need

Worlock concluded that computers, unless they could be offered as one per desk, should only belong in Computer Science class or in Business Studies running spreadsheets, and not in English, history or geography:

"If the BBC wants to take its literacy project [in the direction of high technology], fine. But it could spare us the blather about standards in BBC Basic"[8].

Whilst RML had been calling the BBC's endorsment of the Archimedes "unfair and inappropriate", the BMF was announcing an active campaign against the endorsment, with Fraser suggesting that:

"Approval will further impact adversely on computer education in both curriculum planning and long-term relevance to national and industrial needs. The result is poorly-prepared students and expensive time-consuming re-learning. To perpetuate this situation, in an industry already suffering from serious skills shortages, is very damaging".

Acorn retorted with a counter-attack on Fraser, as Michael Page, Acorn's PR director, suggested that "It's an indication of his lack of knowledge of what computers are used for in schools".

As it happened, the whole thing was under review anyway, as a spokesman for the Department of Education and Science revealed that talks were already under way with the DES, education minister Kenneth Baker - who had launched many of the micros-into-schools schemes previously - and local education authorities, to determine the future prospects for computers in schools.

Despite the numerous schemes, like MISS or various manufacturer "incentives", schools had actually been free, since 1988, to purchase whatever equipment - including micros - they wanted, which they often did, leading to a wide variety of micros in schools.

In an attempt to tame this chaos, the current discussions focused on whether the government should actually issue specific purchasing guidelines, as a new £19 million Educational Support Grant, to be spent on computers, was on the table[9].

The BMF seemed to be having its own issues when Fraser appeared to dismiss half of its members - those in the games industry - as "too volatile", suggsting that games companies were failing to contribute towards "establishing credibility" for the software industry". Fraser said:

"All companies want credibility to be achieved through people who can put in hard work, and the entertainment end of the market has too few people with a long enough perspective".

Paula Byrne, general manager of Telecomsoft responded by saying "I'd dispute the fact that we're a scummy bunch of people who can't see beyond tomorrow".

She didn't seemed too impressed with the mechanics of the BMF, suggesting that "There [are] all these committees which never achieve anything unless you've got someone working at it full time"[10].

Meanwhile, despite RML's protestations, Acorn was still number on in the UK market at least up to the end of 1988, when it was reported that it had shifted 60,000 computers by November of that year and that it had sold 200,000 of its BBC Master micros.

Managing director of the week Harvey Coleman said that "while we predicted level demand for this year, the real demand currently outstrips our ability to supply" - a reference to the 10,000-order backlog Acorn was running at the time.

Coleman also had a beef with RM when the latter company claimed that its Nimbus system was market leader, despite having shifted only 33,000 machines, of which only 19,000 had gone to schools.

Whilst considering whether or not to shop RM to the Advertising Standards Authority, Coleman drily pointed out that "these figures hardly justify RM's present misleading claims"[11].

Away from the politics, the A3000 reviewed well, with Mike Redbridge of The Micro User writing about his explorations of RISC OS and concluding that:

"I doubt I covered even one-hundredth of the options available to me. However, I'd seen enough to be convinced that this new BBC Micro is a superb product. Incredibly sophisticated but utterly simple to use, it's a brilliant successor to the old BBC B. Well done Acorn[12]".

The Year of Unix, again

The arrival of Acorn's RISC OS, as featured on the Archimedes 3000 (or "Archie") seemed to mark something of a milestone, at least according to Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World, who considered the new operating system to be the first serious rival to Apple's Macintosh.

It also broadly coincided with Acorn's release of its R140 "low cost" Unix workstation, at the bargain price (apparently it actually was) of £3,500, or around £11,700 in 2025, for the basic box with no monitor.

Although the R140 looked much like an Archimedes with a bigger disk, there was to be no upgrade for Archie owners, as Acorn reckoned that it had built in too much support cost in the R140 price to be able to offer the same package on a cheapo upgrade.

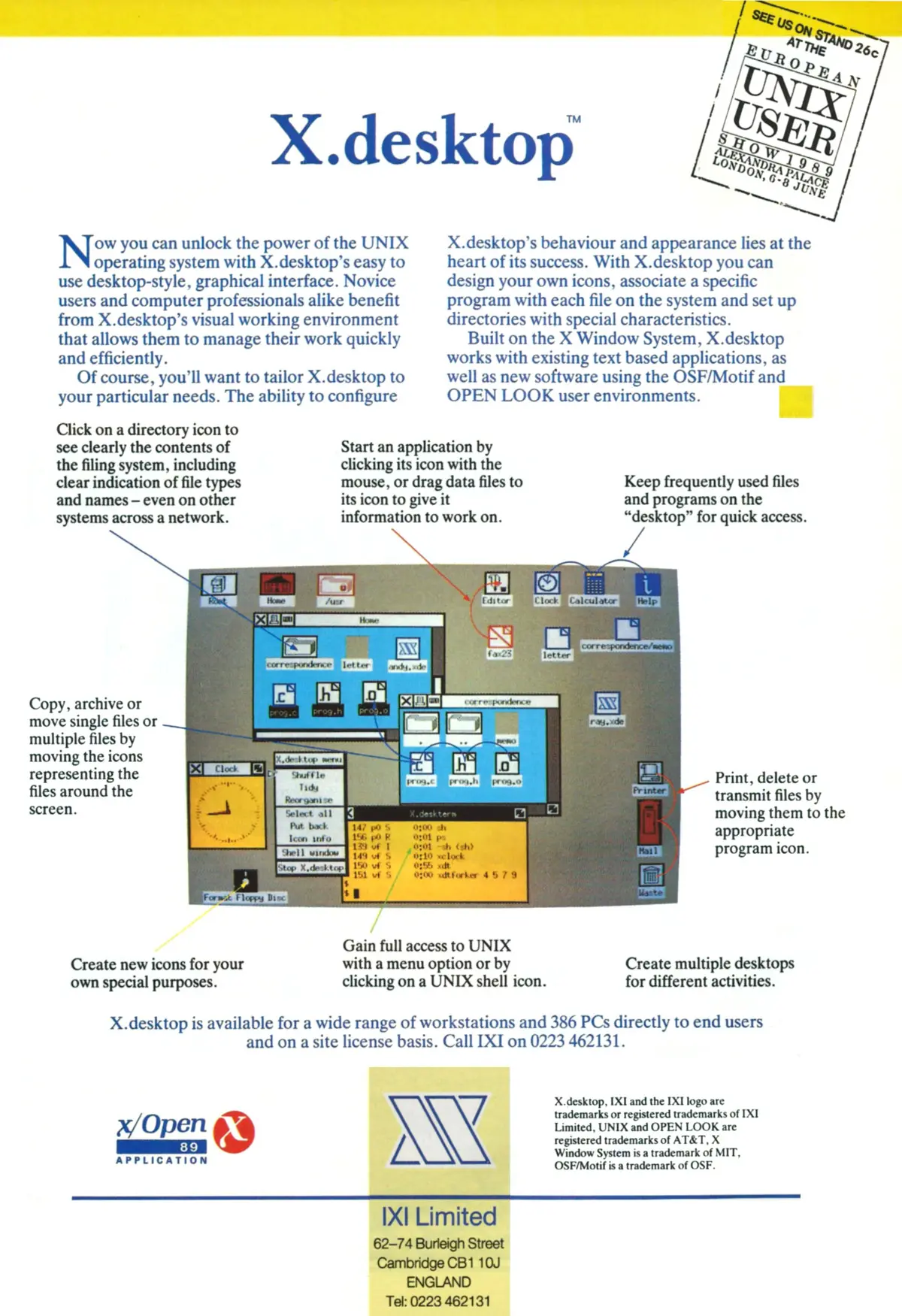

However, the machine did look like it could take on the other high-end workstations from DEC and the current market owner Sun, especially as it used a standard X11-based window manager when running in its Unix flavour - IXI's X-Desktop, the window manager rumoured to have been in the running to provide the desktop environment for Steve Jobs' NeXT project[13].

The machine's secret weapon was its Pixar card-based graphics accelerator

Jobs's NeXT machine, based on the Motorla 68030, had been delayed somewhat from its originally-scheduled release date of February 1988, and ongoing problems with both the hardware and the software meant that it wasn't going to appear until the summer.

The machine's secret weapon was its Pixar card-based graphics accelerator, which was said to have given it graphical power previously only found on machines that cost $55,000 and up - all for less than $10,000.

Jobs was intending to position the NeXT in the educational market, however NeXT board member and billionaire investor H Ross Perot - who would go on to become a two-time US presidential candidate[14], and who had once turned down an opportunity to invest in Microsoft - reckoned he could use his influence to lobby for military and government contracts.

There was also the prospect that the NeXT might become the next power-user machine in the business market, going up against Sun and Apollo, both of which were building low-cost versions of their Unix workstations[15].

NeXT, the company, came over to the UK on the machine's launch in August, for what Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World dubbed the "Steve Jobs Media Hype" event.

The company was being tight-lipped about exactly how many of its machines were being sold, with the only significant examples being Robert Maxell and Queen's University, Belfast.

However, it did admit to selling "hundreds" of machines throughout Europe each month.

Meanwhile, there was some new software available, and the UK branch, based in Windsor to be near the Queen, probably, had a new managing director in the shape of Richard Strong, formerly of Adobe UK[16].

X-Windows and the Thin Client

Ray Anderson, formerly of Torch and now managing director of IXI, © Practical Computing, January 1989Ray Anderson - once of Torch, the BBC Micro add-on specialists, and now managing director of IXI - was predicting that 1990 would be the year that X-Windows terminals would really take off as an alternative to PC networked systems.

This idea pre-dated Larry Ellison of Oracle's popularisation of the term "Thin Client" and was essentially the bridge between dumb text-only terminals and full-blown PCs.

X-Windows was ideally suited to this purpose, as the heavy processing could be done at the server end whilst the "client" would still have enough processing power to handle all the fancy graphics.

A rare consumer advert for IXI's X.desktop, which featured in the June 1989 edition of Personal Computer World. It shows the Mac-like environment - albeit in colour rather than the Mac's monochrome - and mentions support for both OSF/Motif and Open Look. The advert also shows that Unix had apparently become big enough to warrant a trade show, in the shape of the European Unix User show at Alexandra Palace in London, on the 6th to the 8th of June 1989.

X-Windows-based "intelligent terminal" machines like the Xebra, built by Taiwanese company Acer - previously known as Multitec - were fully supported by IXI, with Anderson suggesting that "it [was] positioned well and was a good alternative to a full-blown Sun or Apollo workstation", whilst reckoning that 1990 would see the installation of some 30,000 X-Windows intelligent terminals[17].

Processors had been developing rapidly during the latter half of the 1980s, but software - especially operating systems - had been failing to keep up, not least because Intel was going through a rapid period of development and was releasing new and faster processors with alarming regularity, a situation which caused significant issues for PC manufacturers - the release of a new faster processor suddenly rendering already-assembled stock that was only a few months old obsolete - and which was said to be like Intel "eating its own children".

The Tower of Babel

As something which could actually make use of this new-found processor power, Unix had been predicted as the next operating system of the future for several years by this point, but was held back by its serious fragmentation, with two major camps - the Open Software Foundation, based upon IBM's AIX and also backed by DEC and HP, with a committed spend of $90 million into the new project over the next three years [18] - and the rival System V Release 4 (SVR4) from AT&T, Sun and others, which were together known as the Archer Group.

the split in the Unix world remains unresolved and grows increasingly complex

However, these were both split even further by the provision of different interfaces, like Open Look or PMX, and added to this were other variations like NeXT's NextStep.

The latter was interesting as IBM had approached NeXT, run by Steve Jobs, to develop the windowing system for its own AIX.

What was not known at the time though was whether or not IBM would give the OSF - which had already chosen X-Windows - access to this front end, or keep it proprietary[19].

As Tim Bajarin wrote in March 1989's Personal Computer World, it was a real Tower Of Babel in operating systems[20].

The Archer Group had re-branded itself as Unix International a few months before at the end of 1988, whilst it was revealed that earlier talks between it and the OSF had "broken down".

OSF for its part branded the same talks "unproductive".

As Practical Computing summarised the situation: "the split in the Unix world remains unresolved and grows increasingly complex"[21].

X11, which had evolved out of MIT's 1984 Project Athena [22], looked like it might become the unifying saviour of Unix, and help machines like the Archimedes and R140 become the next standard, instead of Microsoft's OS/2 with its Presentation Manager.

Apple's turf war

This was seen as especially true by the end of 1989 as alternative Unix window challengers like HP's New Wave graphical front-end were either being held up by lawsuits from Apple, or, in the case of AT&T's Open Look, were yet to get off the ground.

Up against this chaos, X-Windows had the advantage of having support from all the major Unix vendors - a situation which crucially meant that X-Windows could be truly portable[23].

By as early as the summer of 1988 it seemed clear that Apple's lawsuit was not really targetted at HP, but was actually aimed at Microsoft, given that the rumours around Silicon Valley were that Bill Gates had already started discussions about badging New Wave as a Microsoft product.

Apple's fear was not really about HP bringing New Wave out, although that was a threat, but that if Microsoft released it as its own it really would find its way into every part of the business computer world, leaving Apple with nothing to differentiate itself.

It was suggested by Tim Bajarin of Personal Computer World that Apple's move was an attempt to both stop New Wave and to give it "time through the courts system to add new features to its own operating system"[24].

A few months before, Derek Cohen of Personal Computer World was similarly speculating that the whole thing was smoke and mirrors, and that Apple was trying to clear away barriers to positioning the Mac as a serious business machine.

A problem for Apple was that it had deliberately priced the Mac to be an aspirational product, but this meant that not only were there very few possibly-influential home users with Macs, but that the machine might be seen as some sort of expensive toy which would be shunned by corporate buyers.

Not only that, but despite its involvement with open-architecture initiatives like OASIS, and desire to see easy-to-use graphical interfaces on mainframe terminals, it also didn't want others to get too close to its own standards.

Whilst it wasn't actually worried about similarities with icons or resizeable windows, it was worried about competing against IBM, if Big Blue ended up with software that looked and felt like its own interfaces, or against HP and its icons-based New Wave.

That really would would spell the end of Apple's desire to capture the business market.

Bill and I talked about it and we agreed that we should not let this complaint escalate to the point that it affects our other relationships

The irony of it all was not lost on Derek Cohen of Personal Computer World, who pointed out that all of these desktop systems were copied from Xerox PARC's Smalltalk ideas.

However, Xerox wasn't sueing Apple because it wasn't a threat, whilst HP and the IBM/Microsoft alliance was definitely a threat to Apple.

Apple had to tread a fine line with its legal actions, as one of its major hooks to get business users onto Macs was Microsoft's Mac version of Excel, and so Apple's John Sculley couldn't risk severing his relationship with Bill Gates.

Sculley was reported to have said "Bill and I talked about it and we agreed that we should not let this complaint escalate to the point that it affects our other relationships", whilst Gates on the other hand had said that the lawsuit had come "as a complete shock"[25].

Microsoft does Unix

A few months later, Microsoft was once again trying to show that Unix wasn't actually a competitor to OS/2, which it maintained was aimed at the multi-tasking single user, whilst Unix was for multiple multi-tasking users.

It got more confusing when Microsoft, which was itself a seller of a version of Unix, known as Xenix, bought 20% of what was the fastest-growing Unix supplier at the time, the Santa Cruz Operation, or SCO - referred to as Eric S. Raymond, author of "The Art of Unix Programming", as the first Unix company[26].

Even Larry Michels of SCO was trying to explain that OS/2 was a "genuine contender" in a completely different market segment. SCO itself was about to launch a development toolkit for its OSF-based windowing system, known as Motif.

Michels reckoned that "with OS/2 it was clear that nobody would design anything serious for it until [Microsoft] had Presentation Manager" and that the same was true of Unix windowing environments.

Michels continued "if the software vendor becomes convinced that it's enough of a standard that he can hang his investments on it, it will start to attract serious developers"[27].

NeXT steps

Jobs's NeXT machine was launched in the US in the spring of 1989, and by the early summer of 1990 it was clear that user feedback generally agreed that the machine was "user friendly".

However that wasn't translating into a move away from traditional platforms for applications, although Lotus was planning to release its 1-2-3 spreadhseet for the machine later in 1990.

The reason for this seemed to be Jobs' "blatant disregard for standards", according to Merlyn Skye, writing in June 1990's Personal Computer World.

Although IBM had licenced NextStep - the NeXT's Unix-based operating system - for use on its own RS/6000 workstations, sales figures were showing that less than 1% of these were actually shipping with NextStep installed.

Meanwhile, the OSF was considering NeXT as an option, but it was not regarded as being anything like a standard, especially compared to AT&T's SVR4 or IBM's AIX.

All of this meant that NeXT's revenues, because it largely relied on royalties from NextStep to generate a return for its investors, weren't what they could have been.

Another problem for NeXT was that by the time the machine was widely available, its 68030 processor was slow compared to the latest SPARC/RISC workstations from the likes of HP and Sun.

This was even more so because of the overheads of running NeXT's desktop system, in which everything was rendered as Display Postcript, rather than as just plain characters.

many previous US and European manufacturers, armed with what were "ergonomically superior" machines, had already failed to conquer a market where businesses were quite happy to buy Amstrad instead of Compaq

NeXT reseller Businessland reckoned that this like the situation with the original Apple Mac, which was also exceedingly slow but where the productivity of the user interface was said to compensate for the machine's lack of performance.

Apparently users agreed that whilst the DTP package Frame ran more slowly on the NeXT, projects were still being completed faster because of the ease in which the software worked.

That trade off might have worked in the US, but the UK market though was said to be the most demanding anywhere in terms of value for money, and many previous US and European manufacturers, armed with what were "ergonomically superior" machines, had already failed to conquer a market where businesses were quite happy to buy Amstrad instead of Compaq.

Jobs however dismissed the price/performance issue and made it clear that an upgrade to the 68040 CPU for his expensive machine would be sufficient to provide all the processing power required, and that there were no plans to move to RISC for at least five years[28].

Market analysts International Data Corporation was forecasting sale of only 15,000 for the year 1990, which was less than it was predicting for IBM's rival RS/6000 workstation.

The figure seemed about right, as around 50,000 machines in total had been sold by the time NeXT exited the hardware business in 1993.

After NeXT was bought by Apple, its operating and windowing system - NeXTSTEP and OpenStep - were rolled in to macOS[29], which would eventually be based on the Unix-like BSD.

Nearly there

By the time 1990 rolled around, it looked like Unix might actually happen as a raft of major software companies started releasing Unix versions of their products.

These included Lotus's 1-2-3 and a promise from Ashton-Tate of a Unix version of its dBase IV product on three of Sun's systems - SPARC, 386 and 68000.

But perhaps the biggest news was Microsoft's announcement of Word version 5.0 for Unix, available from the beginning of 1990, alongside the more prosaic release of Xenix for Amstrad's 386 machine.

January's Uniforum conference in Washington DC was now populated by more suits than propellor-heads

It had also been noticed that January's Uniforum conference in Washington DC was now populated by more suits than propellor-heads, a sure sign, according to Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World, that the "argument about technicalities is no longer what counts" and that the marketing and finance types, after a slice of a potentially big new market, were now running the show.

However, there were still some unresolved issues in the Unix world, including basics like which version of Unix to settle on or which windowing system to use.

The OSF was still trying to sell the idea of its open system, but continuing delays meant that OSF-1, previously expected to be available by December 1989, was still not out.

Apparently, the OSF actually meant December 1990.

The OSF had offered to provide snapshots of the current version, so that developers had something to target, but this didn't look promising as it had already tried this strategy with its windowing system Motif, and that had required eight snapshots before the thing even worked enough to look at.

As Tom Yager of BIX put it "Motif is complex in itself but doesn't hold a candle to the intricacy of the operating system".

Shattered dreams

Thoughts of a Unix takeover turned out to be a bit optimistic, as the challenging operating system never achieved anything like an acceptance on the desktop, at least for "normal" users.

Its indirect spin-off Linux, which would be released a year later in 1991[30], did become successful enough - at least in servers and the infrastructure that runs the internet - whilst also managing to stretch out its own "Year of the Linux desktop" thing for at least two decades[31].

However Linux also suffers from the Unix curse of too many variations (OpenSuse, Mint, Ubuntu, SlackWare, Centos, Kubuntu, Mandriva, Debian, etc, etc) coupled with multiple window managers - mostly Gnome versus KDE, but with a host of others - and so has also resolutely failed to capture the desktop.

As sales of regular PCs decline, that battle is all but over, with the closest to anything approaching a mass-market win being Apple's OSX, which is based on Unix breakaway BSD with added chunks of Jobs's NextStep - but even that has never managed more than 10-15% of the market.

So as computing moves to mobile, maybe it's Linux that finally passes the winning post, albeit via the back door, as it provides the kernel of a certain dominant mobile platform called Android.

---

The partnership between SCO and Microsoft turned somewhat dark at the beginning of the 21st Century, as Microsoft would end up using SCO as a "sock puppet" in a proxy war against the Linux upstart, which was starting to make inroads into Microsoft's server market.

In 2003, SCO sued IBM, part of the original OSF foundation, over copyrights to Linux, in a fatally-flawed and long-drawn-out case that eventually fizzled out in 2016[32].

It was an ignominious end to what had been one of Unix's leading lights, but in a strange twist of fate, Microsoft would eventually move away from the time of Steve Ballmer when Linux was notiously declared a "cancer", to the point where the company now, apparently, "loves Linux"[33].

Date created: 17 December 2019

Last updated: 11 March 2025

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2025. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.