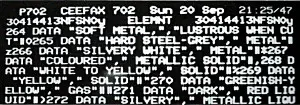

Acorn Advert - 1983

From sales brochure

Acorn Electron

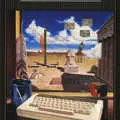

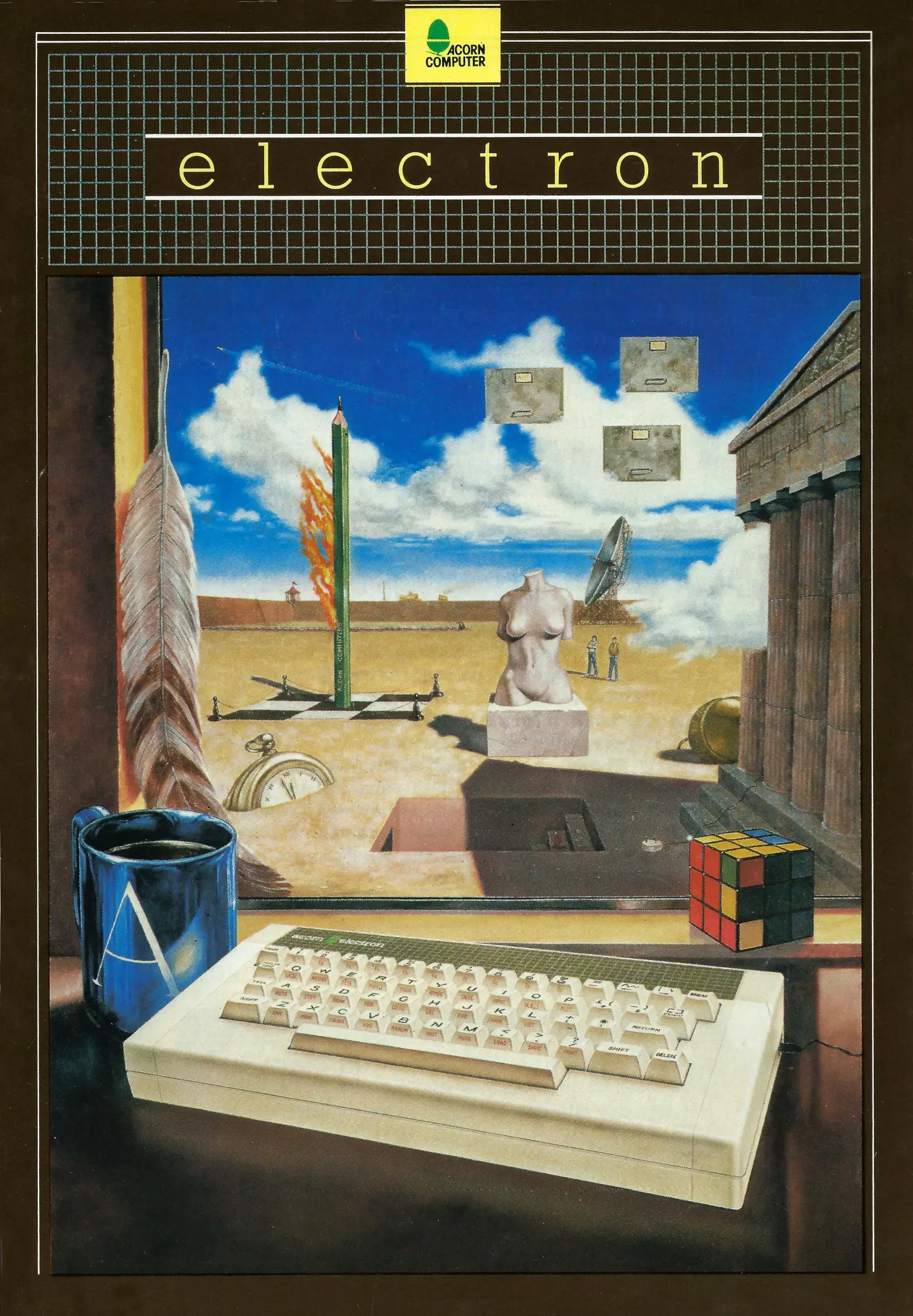

This sales brochure, featuring a very Salvador Dali-esque painting including a Rubik's Cube - one of the defining icon of the 1980s - was for the Acorn Electron, sometimes known as the Elk - a machine first announced in 1982 and intended as a cut-down version of the BBC Micro.

It offered the same 32K as its bigger sibling but had only one channel of sound, slightly reduced graphics and much less in the way of expansion and interfacing.

Despite co-managing-director Chris Curry's claims that the Electron would not befall the production problems that its elder sibling had, the company was running into serious problems by the November of 1983.

Retail orders, at least according to Acorn itself, were over the 150,000 mark but the company had been unable to ship more than a few review machines since it had officially launched the Electron some two months before.

The twelve software packages meant to be available for it were also nowhere to be seen.

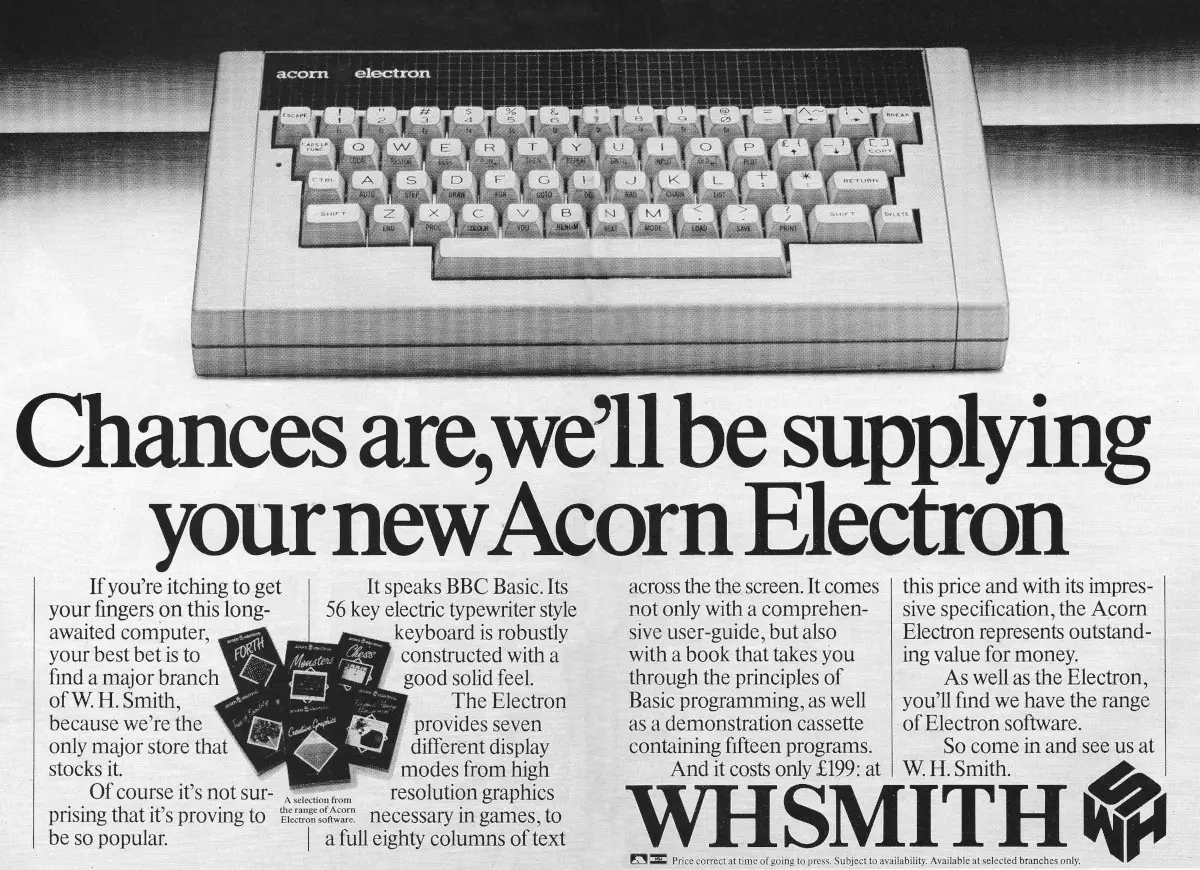

WH Smith, which was initially the only High Street retailer to offer the Elk said:

"We are having to disappoint customers - we are not able to supply demand. What we have had has sold out and while we are expecting more deliveries, the amount will still be well below demand".

WHSmith's advert as the sole High Street retailer for the Acorn Electron. From Personal Computer News, 10th November 1983

The problem was at Malaysian manufacturer Astec and, despite Acorn suggesting that "there isn't a problem with manufacture - they just can't make enough", the company was on the lookout for additional or alternative manufacturing sources, including Wongs of Hong Kong and South Wales' AB Electronics, where BBC Micros were made.

The problem was that Wongs wasn't due on-stream until the end of November and AB wasn't able to start until early 1984.

Acorn would also soon regret that many of its orders were not conditional on them being fulfilled before Christmas, because that's exactly what didn't happen and the warehouses in the New Year were soon full of Electrons that had already been committed to but which were only just started rolling in, having missed the crucial Christmas sales period.

As one industry observer drily noted "Acorn has shot itself in the foot"[1].

It was all a bit ironic as Acorn's Chris Curry had said at the beginning of 1983 that:

"We will not do any advertising until we are completely confident that stocks are available. More than almost anybody else we have suffered in the past from problems of lack of product when the demand is high, and we are not going to let it happen again"[2].

The Electron did eventually sell reasonably well, although this was thought to be largely that first-run production stock, much of which, after the bottom dropped out of the UK home computer market, had been languishing in warehouses for months.

Even by Christmas 1984, when Acorn was already over-stocked with Electrons, the company was still producing extra machines which just added to the stockpile[3].

It was this failure to release on time and Acorn's inability to drop the price of the BBC Micro at a time of all-out price wars (it had an agreement with the BBC preventing any significant price cutting[4]), plus an £8 million write-off trying to break the American market that led to a financial crisis which required a bail-out from Olivetti.

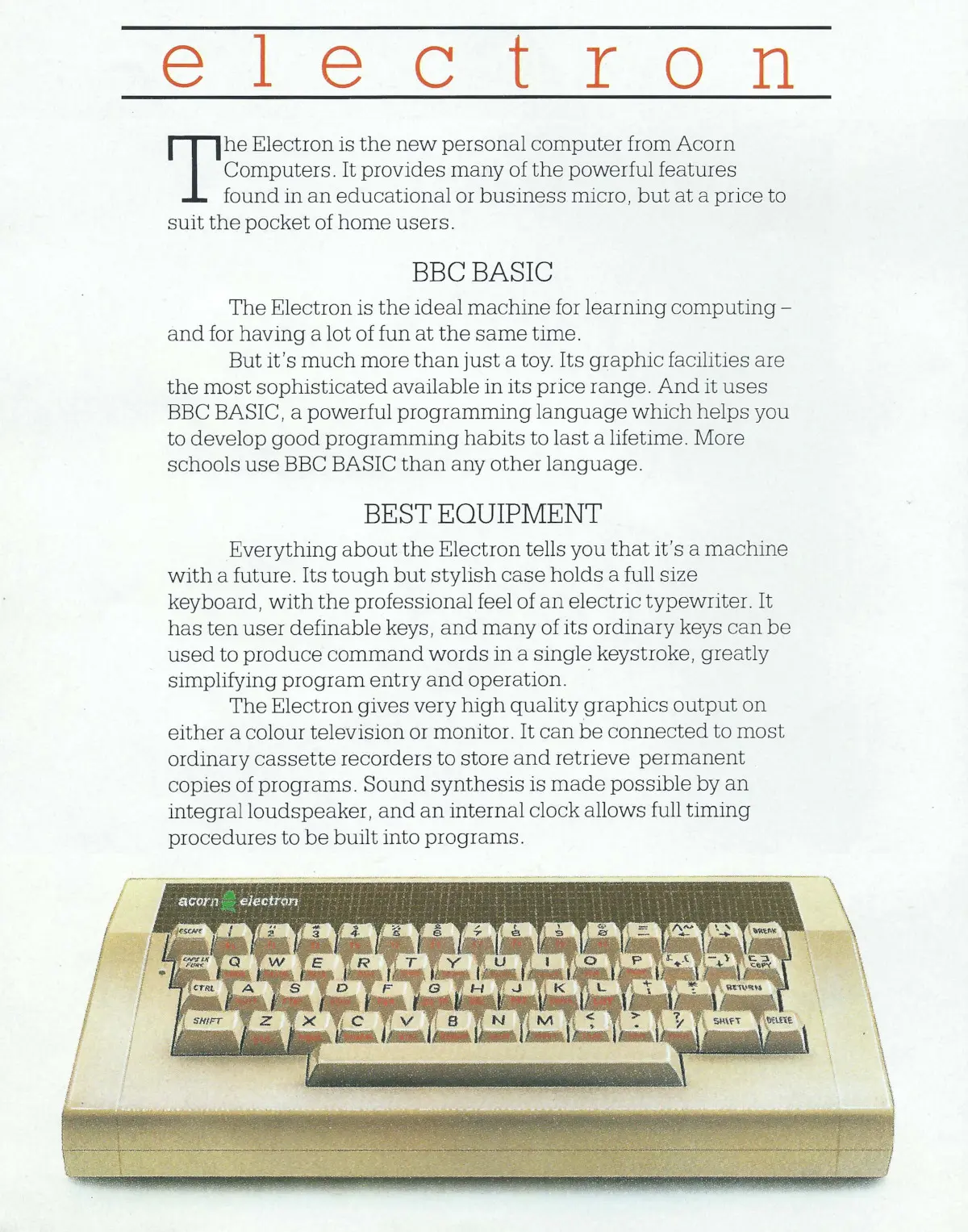

The inside-front page from the A5 Electron sales booklet, describing its BASIC language and equipment features

The cut-down BBC Micro

The launch of the Electron itself caused a few upsets[5], not least with Personal Computer World's Guy Kewney who wrote "I find the question of 'who should buy one' impossible to answer"[6].

This was partly because some of the cost-cutting had involved removing the BBC Micro's "Mode 7" graphics mode, which had been popular in games programs as it required only 1KB memory to use, instead of the 20K needed for hi res.

It also provided simple access to a range of text colours and features like double-height characters, as used frequently in Teletext.

Mode 7's removal meant that some existing BBC Micro software - especially text-based applications and some games, which were seen as crucial to the machine's survival - was incompatible with the new Electron.

Third-party companies like Sir Computers were quick to fill in the gap with products like a teletext adapter, which not only gave download access to the BBC's telesoftware service, but provided the crucial missing Mode 7[7].

Also missing was the BBC's ability to support horizontal scrolling, which was something else useful in games like "Defender".

Kewney was also annoyed that the joystick port had been removed, whilst there were two extra monitor ports. Dedicated monitor ports seemed pointless on a budget machine, whereas cheap computers needed to be able to do games, and the only way the Electron could do these properly was with an additional £60 (£230 in 2024) expansion slot.

However, there were good reviews too. Writing in October 1983's Personal Computer World, Steve Mann said:

"Overall though the Electron is one of the most impressive machines I have seen. The Electron positively oozes quality and there is a wide range of software currently available for the BBC Micro that will run with little or no adaptation on the new machine. I'd plump for a BBC Model B, but if I couldn't raise the readies for that I'd be more than happy to settle for an Electron"[8].

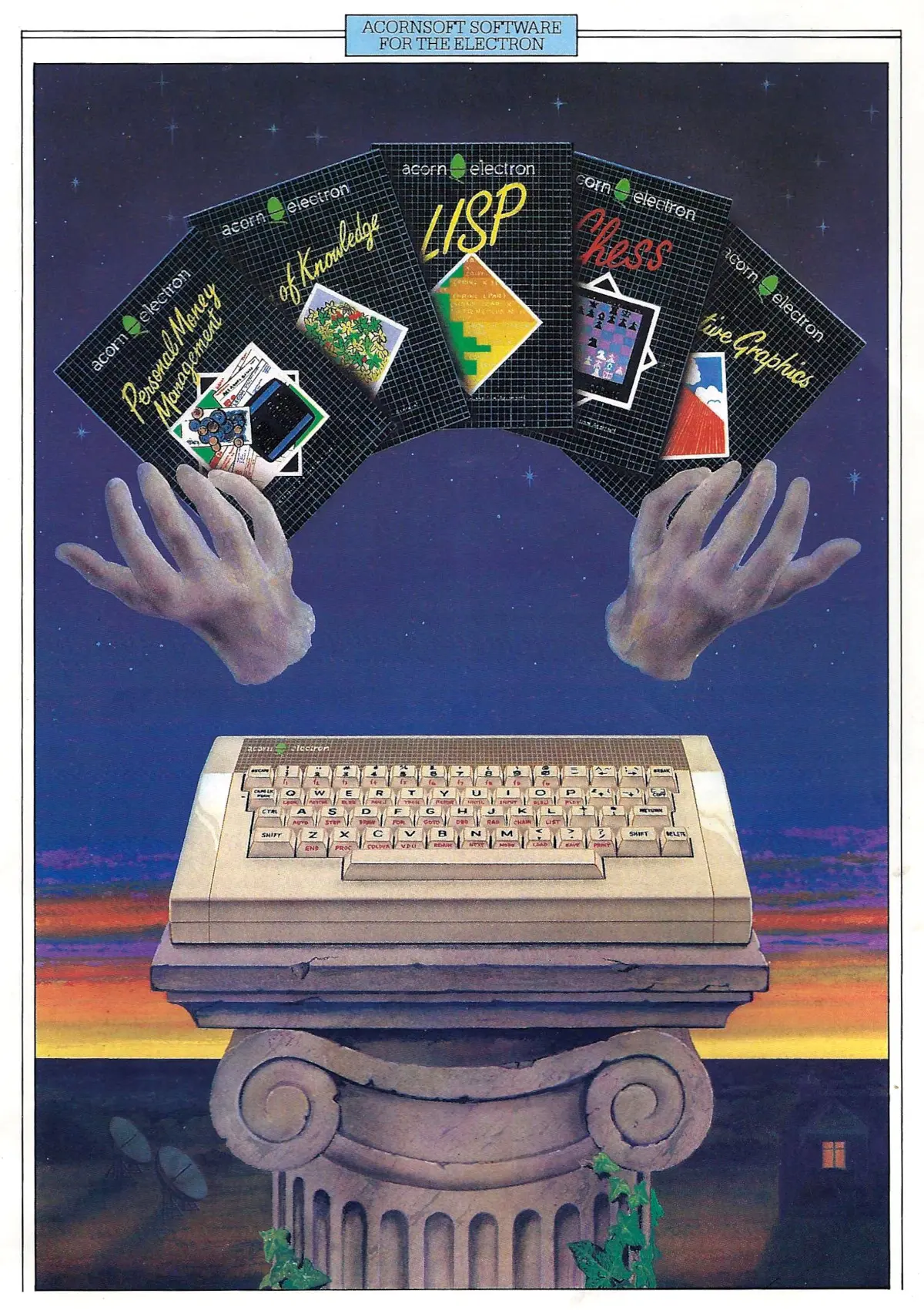

Some Basicode, as broadcast over Ceefax. From "The Computer Book", © BBC Publications, 1982Not content with an Electron crisis, Acorn was having other problems too. It was in the process of providing adapters for the BBC's new Ceefax (teletext) tele-software service, which had originally been intended to launch in May but was still in testing - three months late - in August 1983[9].

The adapters - and the service - were finally launched at the end of September - some two years after they were first advertised.

Even then some of the units leaving manufacturer AB Electronics' factory were shipped without the software needed to actually download broadcast software[10].

Over-the-air software

The Teletext adapters provided similar functionality to those for Prestel, but would allow users to download computer software via their televisions.

It was mostly educational and utility software, some of which was co-produced with the IBA and electronics company Mullard, and which was broadcast and updated in fortnightly cycles[11].

A similar, but radio-based, service was also offered by Dutch broadcasting organisation NOS. It broadcast programs written in an Esperanto-like "Basicode", which would run on 17 different systems, including the BBC Micro.

Software was transmitted at 1,200 baud on a frequency of 747kHz (AM Medium Wave) during a five minute slot at the end of each Sunday evening's "Hobbyscoop" radio program[12].

Radio data was clearly a popular thing in The Netherlands, as the year before Holland's Computer World had announced its TDK 20 Ham-radio interface for the humble VIC-20. At £90, or £380 in 2024, the plug-in cartridge could handle Morse code, CW (Continuous Wave) and RTTY (Radio Teletype) transmissions. According to Commodore Computing International, it was quite the "nifty little unit"[13].

Radio-based software services were expanding in the UK as well, with Bristol Radio West being the first to broadcast data over radio in the early summer of 1983, although this didn't stop Radio Wales from claiming the crown of "the first time that programs have been transmitted directly on a regular basis by any broadcasting organisation in Britain" when they started broadscasting programs using regular FSK for the BBC Micro and the Spectrum on Fridays in October[14].

Conventional non-radio-based software for the Electron, as published by Acornsoft

Meanwhile, Radio West was followed by Portsmouth's Radio Victory in July 1983, which ran a competition in the form of a Spectrum program sent over the air and which contained a line from a song, with the listener/micro-owner identifying the song from the downloaded program winning a £5 gift voucher.

The competition was broadcast for 6 weeks in summer at 1.30pm Saturdays, on 95MHz VHF, and was apparently successful enough that Dave Carson, DJ, said "the response has been so amazing that we are looking at ways of making the competition available on other micros as well"[15].

The first regular radio programme dedicated to microcomputers, albeit without data, was thought to have been a slot aired in the spring of 1982 on Radio WM's "Great! It's Saturday" programmes, as broadcast by BBC local radio in the West Midlands[16].

The BBC followed up in early 1984 with a new regular computer programme called The Chip Shop, hosted by Barry Norman and broadcast on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 5pm, with a "pop" version of the programme broadcast on Radio 1 at 7.33 in the morning, with software broadcast earlier in the morning at 5.55am.

Part of the Radio 4 programming included an additional four nights of over-the-air software broadcast, using the same Basicode as the NOS service, at 12.23am after the shipping forecast.

The BBC's commercial arm was also selling Basicode tapes, but the arrangement with the Dutch included, as well as a conventional royalty agreement, a clause that it could not make a profit from sales[17].

The BBC Micro's rival - the Sinclair Spectrum - was not initially on the list of supported machines, as the Speccy wasn't that popular in the Netherlands and so a translation from Basicode to native BASIC was not initially available for it, however the BBC expected to have one ready shortly after the programme started[18].

The Tomorrow's World team of early 1982, in what looks suspiciously like the Blue Peter garden: Judith Hann, Kieran Prendiville, Michael Rodd and Su Ingle, © Your Computer, February 1982The BBC had actually experimented with over-the-air software two years before, when flagship TV science programme Tomorrow's World had broadcast a couple of minutes of white noise containing software for Sinclair's ZX81 and the Apple II in January 1982.

The programme hadn't expected much in the way of response as it assumed that only a few über-nerds with decent hifi would be able to record the broadcast and get it on to a computer, however a whole mailbag-full of letters turned up.

The programme's producer Trevor Taylor reported:

"Nobody had much faith that it would work - maybe a few people able to take the sound directly to a quality recorder, but in fact we got letters from people who'd got a usable program just by putting a microphone near the speaker; even on the ZX81!".

The software itself didn't do much apart from show the Tomorrow's World end credits, including the recipient as one of the presenters, but according to Popular Computing Weekly it "Delighted the hundreds who successfully ran it and proved that the demand existed"[19].

The actual XZ81 Basic program, as broadcast by Tomorrow's World, © Your Computer, February 1982One of the most unexpected things to come out of the test broadcast was the number of people who had used VCRs - which in 1982 were still expensive and fairly rare - to record the program in order to "dub off the audio" in order to run the software.

It was also revealed that more than 2,000 people, from the Shetland Isles to France and apparently including two six-year-olds plus a bloke who had claimed to have seen the first-ever TV broadcast some 50 years before, had written in to say that they had succeeded in getting the over-the-air program to run.

The response was such that the Tomorrow's World team was considering running a follow-up experiment with longer broadcasts, to be shown at night[20] after "closedown" - that thing back in the day before 24-hour TV when telly stations would play the national anthem and actually stop broadcasting for a few hours overnight.

The Electron comes home

Back in the September of 1983 - at the height of Acorn's Electron manufacturing and delivery crisis - the company announced that it was bringing production of the machine back to the UK.

The company's current production of 20,000-25,000 units per month was being manufactured in Malaysia, but the plan was to bring some production back to one of the firms which had been producing the BBC Model B - either AB Electronics, Race Electronics or Keltek.

This would have freed up some capacity in order to back up a "Cambridge-based assult on the American market"[21].

As it happened, BBC Micros for the American market ended up being built by Wongs, a Hong Kong-based assembly specialist that started out in 1965 making transistor radios. The US version, which Raymond Yap of Wongs said was "a damn good machine" comprised a BBC B with built-in Econet, View word-processor and "an American version of Kenneth Kendall" - a reference to the speech-synthesis chip with the voice of the famous BBC newsreader, which was available in the UK.

Wongs also built machines for IBM, Atari, Coleco, Apple, Camputers, Torch and Osborne, some of which - like Atari - had moved production to the Far East in order to try and improve lost profit margins.

The reason for this, according to Yap - somewhat darkly - was that "Overhead costs in the Far East can be manipulated more than in other parts of the world - there are no pension schemes, National Insurance payments or other social committments to be fulfilled"[22].

"We would obviously prefer to be manufacturing in the UK"

Chris Curry of Acorn had previously discussed in a February 1983 interview in Popular Computing Weekly why Acorn had chosen to off-shore its manufacture of the Electron. "One reason is that duty on components in the UK is thoroughly unacceptable - notwithstanding the fact that overseas suppliers have to a certain extent adjusted their prices to take account of it".

This was a reference to the situation that Sinclair had also been grumbling about where assembled systems could be imported with only a 7% levy but components attracted a 17% tax[23].

Curry continued:

"The main reason we will be manufacturing the Electron overseas is that we wanted to apply some fairly radical production techniques. We find there is less resistance to change in countries like Hong Kong and Singapore - they go straight in with capital expenditure. British companies find this difficult to do and there wasn't anyone in the UK who was already set up for it. We would obviously prefer to be manufacturing in the UK, but the first run, at least, will be in Singapore"[24].

Obviously this was before the machines ended up being manufactured in Malaysia instead.

In early 1984, it was confirmed that AB Electronics was getting the order for the next 100,000 Electrons, providing 100 new jobs at their new Rogerstone, Gwent factory, which was said to have the most advanced electronics production equipment in the UK[25].

There was some urgency in getting the Welsh factory going as the Malaysian assembly line had not been able to produce anywhere near sufficient quantities, and by March of 1984 the total order backlog was standing at nearly 250,000 machines, whilst the limited supply in the UK had virtually dried up.

At the time of the original announcement, it was expected that the Gwent factory would be churning out 4,000 Electrons a week from the start of the year, but it was looking like it wouldn't be until April at the earliest.

Wongs' new Electron production line in Hong Kong was also not expected to come on stream until May[26].

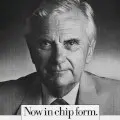

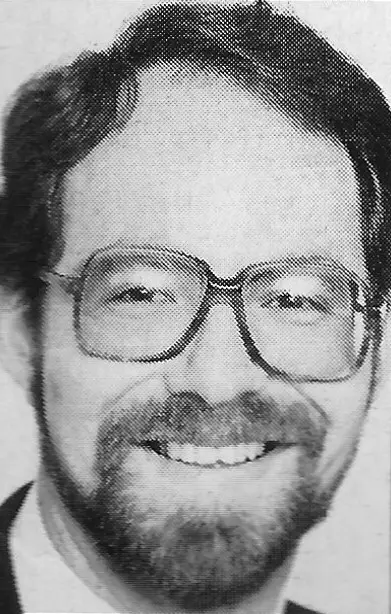

Tom Hohenburg, Acorn's Marketing Manager, © Acorn User, April 1984The problems of supply were also compounded by what was thought to be an unusually high failure rate for those Electrons that had actually been shipped to buyers, with returns due to faults running at between 8% and 25%[27], compared to 5% for the other Cambridge companies like Jupiter and Sinclair and only 1% for Commodore and Apple[28]. Acorn was committed to replacing defective machines as a matter of priority.

A month later, Acorn's marketing manager Tom Hohenburg confessed that the problems had been down to the ULA - a custom-made chip from Ferranti, made in Chadderton and which contained much of the Electron's functionality - but that finally deliveries to dealers were slowly increasing[29].

Meanwhile, Acorn was having to deny reports that the Malaysian production line had been forcibly "closed down" because of production difficulties. Instead, an Acorn spokesman suggested that "all that has happened is that they have produced the number of Electrons they were under contract to produced" and so the contract had come to a natural end[30].

The BBC Micro Model B's Hong Kong production was then to be directed at the American market, but Acorn ultimately failed to make much of an impact in the US - the £8 million it cost to try almost led to the company's collapse.

For more information, The Register has one of its excellent in-depth articles on the Electron, including observations from the one of the Electron's designers, Steve Furber.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2024. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.