ACT/Apricot Advert - April 1985

From Personal Computer World

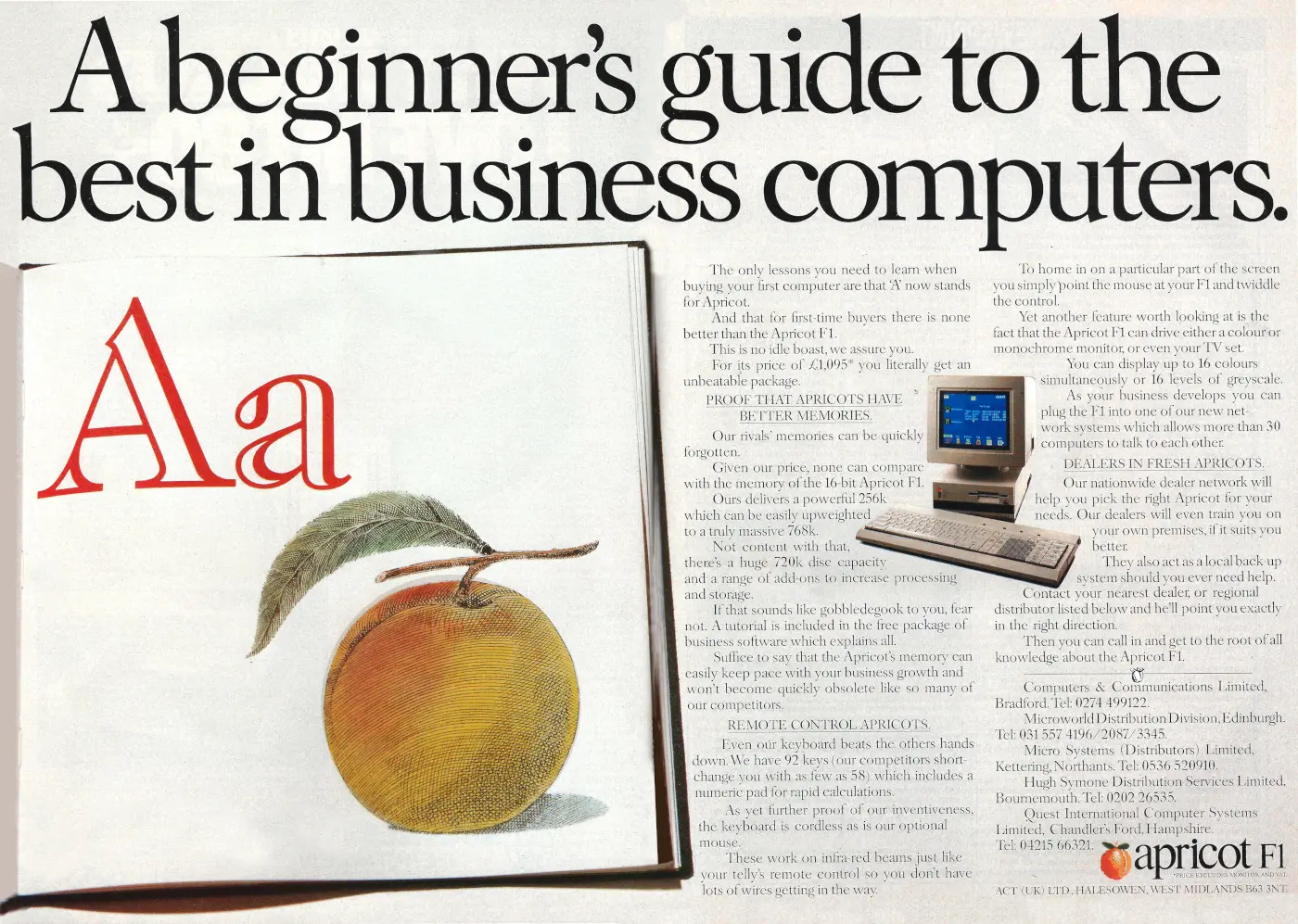

A beginner's guide to the best in business computers

ACT had carved out a briefly-successful niche in the UK with its Apricot range of micros, several of which touted their "Sirius" compatibility, rather than the usual IBM.

However, when the company launched in the US in early 1985 it appeared to incur the wrath of Apple, particularly as ACT's first advert in the States, which appeared in publications like the Wall Street Journal, featured a cheeky dig with a juicy apricot next to a dried out apple, as in the fruit, obviously.

Apricot even managed to steal some of Apple's US dealers, but the word from Cupertino - as reported in Personal Computer World - was that "there are to be no little apricots growing in the Apple orchard".

The first time ACT had tried to crack the US market, it sold only 110 machines - the US market simply couldn't imagine a UK computer and tended to consider, as Personal Computer News put it nicely, the US and Japan as being part of the Computer Age and the rest of the planet "as various grades of 'world', that is to say Communist, Free, Third, Post-Industrial, Developing, etc.

Apparently news of the UK's "large, turbulent micro scene" often came as a shock to those across the pond, or as a former resident of Canada and now Microsoft employee in the UK Bryan Miller put it, when referring to how machines like the ZX Spectrum had seemed alien:

"For me Sinclair was like Sea Monkey ads in the back of comic books, I wasn't entirely sure they existed, and if they did they wouldn't resemble the ads. I never knew a soul who owned one until I moved [to the UK], where [Sinclairs were] all people owned and my computer history was considered similarly exotic"[1].

Stung by its initial failure, the second time ACT tried to take on the US market it came armed with a reported $7 million in launch budget and a new line of MS-DOS-based micros to take on Apple.

It also had agreements with Ashton-Tate, the makers of dBase II, Microsoft and Software Publishing which gave it a good range of well-known software packages to offer the small business market[2].

As a result of the threat, Apple UK was given "more commercial freedom than the money-hungry parent normally gives subsidiaries" in order to destroy Apricot, with one dealer apparently telling Guy Kewney that "whatever they say to you officially, Apple UK doesn't have to make a profit until ACT is no longer a threat"[3].

Part of Apple's reaction involved targetting the educational market, where the F1E - the educational variant of the F1 - was was thought to be making headway.

Apple's "Our Kids Can't Wait" campaign involved dropping the price of its Apple IIe machine to only £400 for educational buyers - the same price as the schools' favourite BBC Micro - although Apple's discount wasn't limited to one-per-school, unlike the UK Government's Micro Education Programme (MEP)-funded scheme, which provided a 50% discount for Acorn, and later Research Machines' and Sinclair's micros.

However, since the Government's MEP had finished in 1984, the whole educational market had opened up - before then about 80% of schools were thought to have bought Acorn's machine[4].

When MEP finished, Commodore - which hadn't featured much in schools ite'>IT since the heady days of the late 1970s when the PET reigned supreme - even pitched in with a Commodore 64 bundle including the 1541 super-slow floppy disk drive, a copy of Logo and Simons BASIC for £300, a discount of £170[5].

It would be a theme that Apple would return to again, including in the spring of 1986 when it (presumably) sponsored the first Apple University Consortium, a three-day love-in held in Cambridge where 200 delegates from universities in 37 countries met to discuss the role of the Macintosh as an educational machine.

By then, the "threat" to Apple had moved on to Commodore's Amiga and Atari's ST, but John "Pepsi" Sculley, chairman of Apple since the acrimonious departure of Steve Jobs at the end of 1985, was dismissive of the upstarts suggesting - depressingly accurately as it turned out - that "the future of mainstream personal computing lay in two architectures - the IBM PC and the Macintosh".

Even the two renegade micro companies - Commodore and Atari - seemed complicit in this future, with both of them offering some form of PC compatibility - Commodore offering PC emulation for the Amiga as well as a range of PC-compatibles, and Atari offering CP/M emulation, which it ended up offering for free to anyone taking a blank 3½" floppy to an Atari dealer[6].

Meanwhile, Apple was feeling bullish - it would be another 10 years before the company almost went bankrupt for the second time - as its profits had trebled over the previous year to $32 million (£79 million in 2026).

Somewhat unexpectedly, the only other computer company around at the time making that sort of profit was Amstrad[7].

Meanwhile, back at the end of 1984, ACT had announced a new retail venture with Tandy which was to combine ACT's 20 Computerworld shops and Tandy's 49 Computer Centres in to a new European-wide retail chain known as TA Computerworld.

Tandy was also expected to sell some of Apricot's range in 140 of its general retail shops and 290 Tandy dealers in the US, although Tandy's finance director Andrew Barwood said "[we are] still undecided about the rest of the range, but we are definitely interested in the F1".

ACT had also taken over the German Beaugrand Datentechnik computer and office equipment company, which, combined with its wholly-owned French subsidiary, the recently formed Apricot Inc. in the US and a Far Eastern jointly-owned distributor, was giving the company something of a world-wide presence[8].

The first fruits of the ACT/Tandy tie-up appeared to be significant price drops from Tandy, which shaved £200 off the price of the Tandy 1000 and £500 off the hard-disk-based Tandy 2000, which was down to £2,700 (£10,800).

Personal Computer World reckoned that this "said nothing about [Tandy] not wanting to look overpriced next to the Apricot"[9].

Within a year, the two companies had hoped to increase the number of outlets from an initial 50 up to 150.

This was one of several changes in the industry that potentially spelled doom for the independent dealer, which could no longer hope to compete on price but had to rely on adding value through skills and services.

This was by no means a bad thing in and of itself but was highly precarious, at least compared to making steady revenue from margins on hardware until the next price war broke out.

Other big companies like Apple and Commodore had also made changes to dealer schemes which, in Apple's case, required an up-front purchase of £60,000 worth of gear, which is a not-inconsiderable £241,300 in 2026 money.

As Martin Banks wrote in April 1985's Personal Computer World, this sort of structural change left independents having to try to sell to people who didn't think they needed or wanted a computer, a process which required "careful nurturing" and cost time and money. The alternative was that such people would go with what seemed safest. Banks concluded:

"Over the next year or so, 'safest' is going to mean IBM. Big Blue wants all the business and means to get it. Then, I suppose, there won't be any choice at all"[10].

This was all part an ongoing part of a process which had been happening in the wider computer industry since at least 1982 as, even then when the industry was just starting to explode, there were worries that it was already coalescing around the major incumbents.

This left the "wings" of the industry - the very cheap, where Sinclair dominated, and the high-end, where companies were happy to sell a few machines a week but make thousands on software - pulling ahead of the body, where the mass of moderate-sized companies selling moderate micros at moderate prices existed.

The safety net that IBM offered, which appeared to explain why people would continue to buy their under-powered over-priced hardware, easily trumped the excitement of yet another new entrant.

Small micro companies simply lacked the volume to compete at the cheap end of the market, and didn't have the staffing or resources to compete with the massive dedicated customer-services teams of companies like IBM.

As the August 1982 editorial in Practical Computing concluded:

"There really will not be any room for anything but the most specialised small manufacturers. It will be like the car industry - at the turn of the [19th] century there were dozens of builders [in the UK]. Now there are two and a half. So it will be with us"[11].

At around the time this advert came out, arch-rival-in-the-education-market Acorn was in the process of being rescued by Italian company Olivetti.

The significance of a "foreign" company owning the manufacture of the flagship BBC Micro didn't go unnoticed and was a situation that ACT said was "untenable". ACT's Peter Oldershaw said that:

"People really must understand that Olivetti has control of the company".

Whilst Oldershaw's boss Roger Foster followed up with:

"We will certainly be getting in touch with the BBC to suggest, politely, that the time has come for a change".

Perhaps unexpectedly, Clive Sinclair, who remained bitter about losing the BBC contract for years, was a bit more sympathetic, saying of the Acorn buy-out that:

"It's a great relief - it would have been a tragedy if Acorn hadn't managed to re-structure"[12].

Meanwhile, in May of 1985, ACT announced that it was reducing the price of its F1E model by £200, bringing it down to £595.

This was within shouting distance of arch-rival Acorn's BBC, considering that the F1E included a 315K 3.5" floppy disk drive, as well as a whole load of free software.

Oh, and it was running a 16-bit 8086, rather than the BBC Micro's 1975-designed 6502.

A spokesman for ACT said:

"We are aiming the new-style machine at sixth-form and higher-education colleges, and the BBC machine is the main competitor".

The F1E at its previous price of £795 was thought to have sold only around 200 units[13].

The product becomes the company

Both the F1, and its education equivalent F1E were dropped entirely at the end of 1985, together with the company's portable business machine.

The move marked ACT/Apricot's shift to higher-end business machines, although Apricot's group MD John Leftwich pointed out that dropping the F1E didn't mean that the company was pulling out of the educational market. Leftwich continued:

"We felt that end of the market has become very competitive with ferocious pricing. We have made very little money with these products - the dealer margins were insufficient, and we were getting inadequately-supported users as a result".

As a replacement, Apricot was continuing with a 512K version of the F1, running the GEM GUI. It was expecting to sell out its remaining stocks of F1's and F1E's into 1986[14].

The move came at a time when the company announced that its profits had dropped from £3.8 million in the first half of 1984 to £1.27 million in the same period in 1985.

It was also when Apricot became the company's name, rather than just one of its products.

Apricot also ended up writing down £5.1 million of stock, mostly of its portable machine which had sold poorly, which combined to leave the company with a net loss of £4.6 million (£20 million) at the end of 1985.

It had also laid off 100 staff from its UK operations and a further 20 in West Germany[15].

Apricot's AT Computerworld chain crashed at the beginning of 1986, leading to a break up with former partner Tandy. One-time editor of Personal Computer World, Peter Rodwell, suggested to that magazine's Guy Kewney that he could write an article about it entitled the "Texas Chain Store Massacre", in a nod to Tandy's Forth Worth roots[16]

Date created: 08 December 2019

Last updated: 15 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.