Oric Advert - 18th August 1983

From Personal Computer News

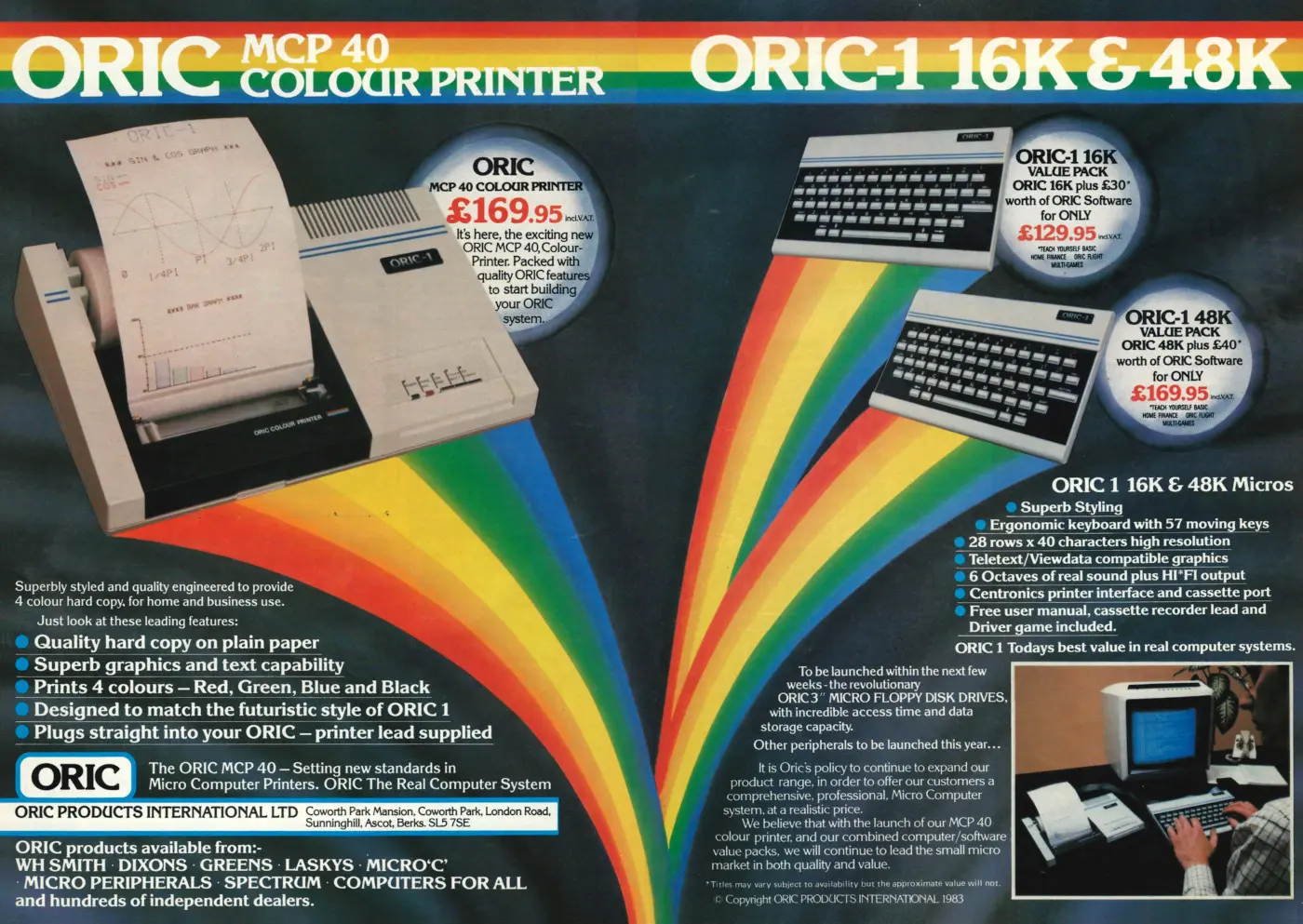

Oric-1 16K and 48K Micros

The Oric-1, designed by Tangerine and manufactured by Oric Products International, a company created by Tangerine to sell the Oric - was aimed at the Sinclair Spectrum market.

The models and prices were similar, and even the graphics in the advert alluded to the Spectrum's product design.

It's nearly a year after the Oric started trickling out, and not much has changed, although the prices for the two machines have actually increased, with the 16K model increasing from its December 1982 price of £99.95 (about £470 in 2026) to £129.95 (£570), although with £30 of free software included to soften the blow.

Oric was finding it too difficult to make any sort of profit on the 16K machine at its original price, although iit did drop eventually back under the magic £100.

This advert includes a reference to teletext/viewdata-compatible graphics. The Oric was an early pioneer of online usage in home computers and had been designed from the outset to be able to connect to bulletin boards and the UK's Prestel service.

This capability may have been down to the influence of Peter Harding - Tandata's former managing director and now at Oric - as Tandata, another spin-off from Tangerine, was already manufacturing the "Tantel" Prestel adapter.

Tandata was believed to be getting ready to sell a large number of adapters to the Halifax Building Society, just as Harding left the business.

The Tantel was built in association with Prestel, which also commissioned software for the Apple, ZX81, TRS-80 and Commodore PET. It cost a bargain £205 (about £980 in 2026 money)[1].

It was comforting to know that the UK's own Government seemed oblivious to the fact that Prestel adapters were even being made in the country at reasonable scale.

Kenneth Baker - the minister who had launched the "micros in schools" schemes in 1982 and who was also in charge of all things "videotex", including Prestel - had assumed that they were all imported, when the topic came up in an early 1982 interview with Your Computer. He said:

"You have drawn my attention to the Tantel and it sounds very interesting. I will look into it. This is the kind of thing I am looking at to see if I can give some assistance in one way or another - through trade not aid"[2].

Oric released its own modem in January 1983, which became the first affordable modem aimed at the home market, retailing for only £60 (£260).

It had even beaten Sinclair, which had intended to be first with a low-cost modem for the Spectrum but was delayed until the Spring of 1983, by which time both Oric and Micronet modems were available (the latter cost from £50-£100).

Oric also provided its own "dial-a-game" service called "Aladdin's Cave", from which a variety of programs could be downloaded "day or night".

Peter Harding said of this service "Telesoftware is going to be the medium of the future for software"[3].

The Oric didn't get off to a very good start when it was launched, late, despite OPI - just like its contemporary Camputers - claiming that it had learnt from Sinclair's mistake and wouldn't be announcing its machine as "available" when it actually wasn't, even though that's exactly what it did.

Dogged by delivery delays on the Oric's ROM chips, the company attempted to "preserve the illusion of delivery" by letting a few pre-production models trickle out for review in time for the Christmas of 1982, as well as announcing that it was going to give away a free cassette copy of Forth with every machine[4].

Guy Kewney, writing in Personal Computer World - one of the UK's biggest computer magazines - didn't even get one. "What magazine do you write for?" they asked, when questioned.

Colleagues at Personal Computer World, however, had churned through up to four machines each before getting one that worked fully, with the micros being unable to load and save programs, and the early ones not even being able to edit.

Apparently, when asked why the machines were all faulty, the response was that:

"the sample[s] sent were only functional in the hardware sense. Software would be supplied when it was working"[5].

Barry Muncaster of Oric, © Popular Computing Weekly September 1983Oric's 16K version of its machine - which would provide the magic sub-£100 model that Oric was after - was further delayed, partly by "technical difficulties" but also, apparently, by demand for its existing 48K model.

OPI's managing director (and co-founder of Tangerine) Barry Muncaster explained that both versions had originally used the same design but that:

"We would have had no problems if the specification for a particular chip had not changed just prior to manufacture. [We had to] completely change the 16K version's printed circuit board design - which, from start-up to production, has taken 12 weeks. From a manufacturing point of view, [the 16K machine is] a totally different product. This has caused a delay".

At least Oric was being a bit more pro-active than Sinclair with its delays as, rather than sitting on the cashed cheques of thousands of customers, it was instead providing extended loans of 48K machines which would be swapped out for the 16K model when they finally appeared.

This was the second of Oric's models to run into problems - an additional 32K model, which had been announced the year before in November 1982, had been shelved in January because of a "chip incompatibility problem"[6].

When the 16K machines became more freely available, the Oric was reviewed again in Personal Computer World. Steve Mann wrote that:

"let it be said that the Oric-1 represents extraordinarily good value for money. To produce a 16K colour and sound machine, with Centronics printer interface and RGB monitor socket fitted as standard, at a price of under £100 is quite an achievement".

He went on to reflect on the fact that the four models he'd looked at all had EPROMS instead of final ROM chips which meant that:

"it is impossible to recommend the Oric-1 unreservedly. When the final ROMs have been installed and bugs have been dealt with, and if Oric re-writes its manuals to a higher standard, then the Oric-1 should be a best-selling machine. It's just unfortunate that Oric should have set about marketing its product in this unprofessional and slap-dash way - it can do the company's reputation no good"[7].

The bugs referred to were in BASIC and didn't get fixed until the Oric-1 was updated and re-released as the Atmos in 1984.

By the spring of 1983, Oric was said to have "stopped making enemies of shopkeepers" and was starting to make friends by actually having machines available.

Software was starting to appear as well, with the first package to reach the offices of Personal Computer World being a business-aimed personnel records system retailing for £15[8].

However, software was still a problem and there was also, in some quarters, a feeling that Oric wasn't doing all it could to support games. Personal Computer News wrote in its September 22nd 1983 issue that:

"Hidden inside the Oric is a game machine struggling to get out. The problem for software writers is that Oric has been reluctant to reveal just how the insides work. The result is a challenge to the games writers to find out all the tricks and special effects for themselves"[9].

About a month later, Oric announced that it was to launch a new machine to go after IBM's rumoured low-cost Peanut - the PC Jr.

No-one quite knew what IBM's new machine would be, with Gartner's Tom Crotty suggesting that:

"It will be an Intel 8086-based machine - that is our best guess at this point. With IBM there is nothing sure until it is launched".

Meanwhile Oric's Barry Muncaster was convinced that:

"The IBM Peanut will be hugely successful and set a standard and we will be there with it. Oric will produce a product which the Peanut will be compatible with"[10].

The Peanut surprised many by being a failure and it never even made it to the UK, whilst Oric never launched a competitor machine.

In October 1983 Oric announced that 70% of its sales were going abroad, with 70% of those going to France, where Oric had shifted 35,000 units since February.

This actually made it France's top-selling micro, even beating Sinclair.

Back in the UK, things were less positive - 21,500 Orics had been sold since its launch[11].

The company received additional funding in early 1984 when it was acquired by Edenspring Investments, which gave it assets of nearly £5 million (about £21 million in 2026 terms) which were to be used to further develop Oric's products[12].

The targetting of Sinclair was such that Harding expected that:

"since [the Oric] offers more features than the Sinclair, the Spectrum will have its price reduced within a few months".

Sinclair wouldn't have been too worried though as at the time it was running a three-month order backlog and had already shifted 200,000 units.

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 15 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.