Oric Advert - March 1984

From Your Computer

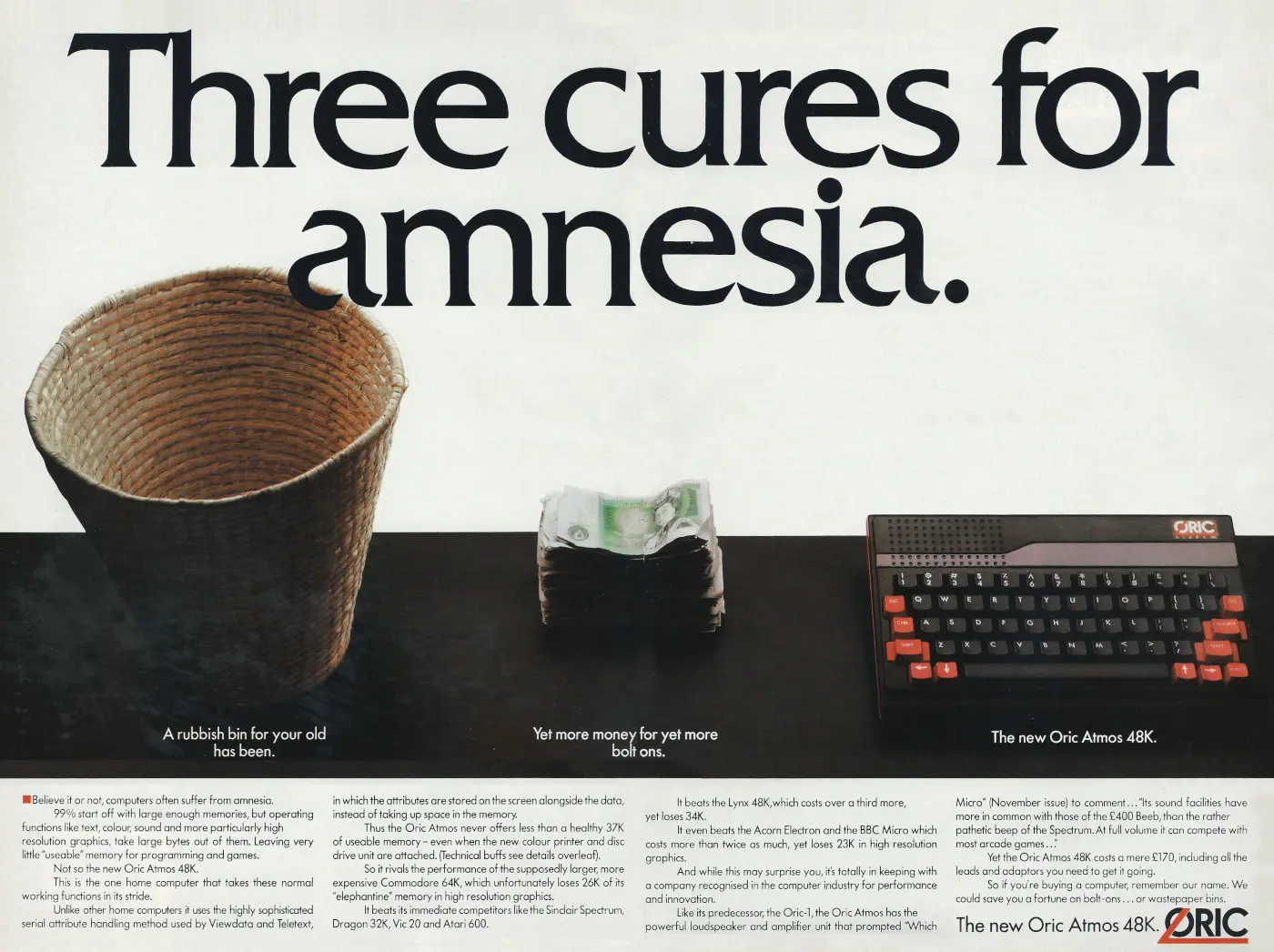

Three cures for amnesia: The new Oric Atmos 48K

Billed as a new computer when it was launched at the Which Computer? Show at the NEC in Birmingham between the 17th and 20th January 1984[1], the Atmos was in reality just an update of the original Oric-1 in a new case with an improved keyboard, an updated ROM - which removed most, but not all, of the previous bugs - and a better manual.

Oric's Peter Harding claimed that "all those bugs in the old operating system have been ironed out and cassette loading has been much improved"[2].

Harding also hoped to offer buyers of the original Oric the chance to upgrade for about £50 (£210 in 2026).

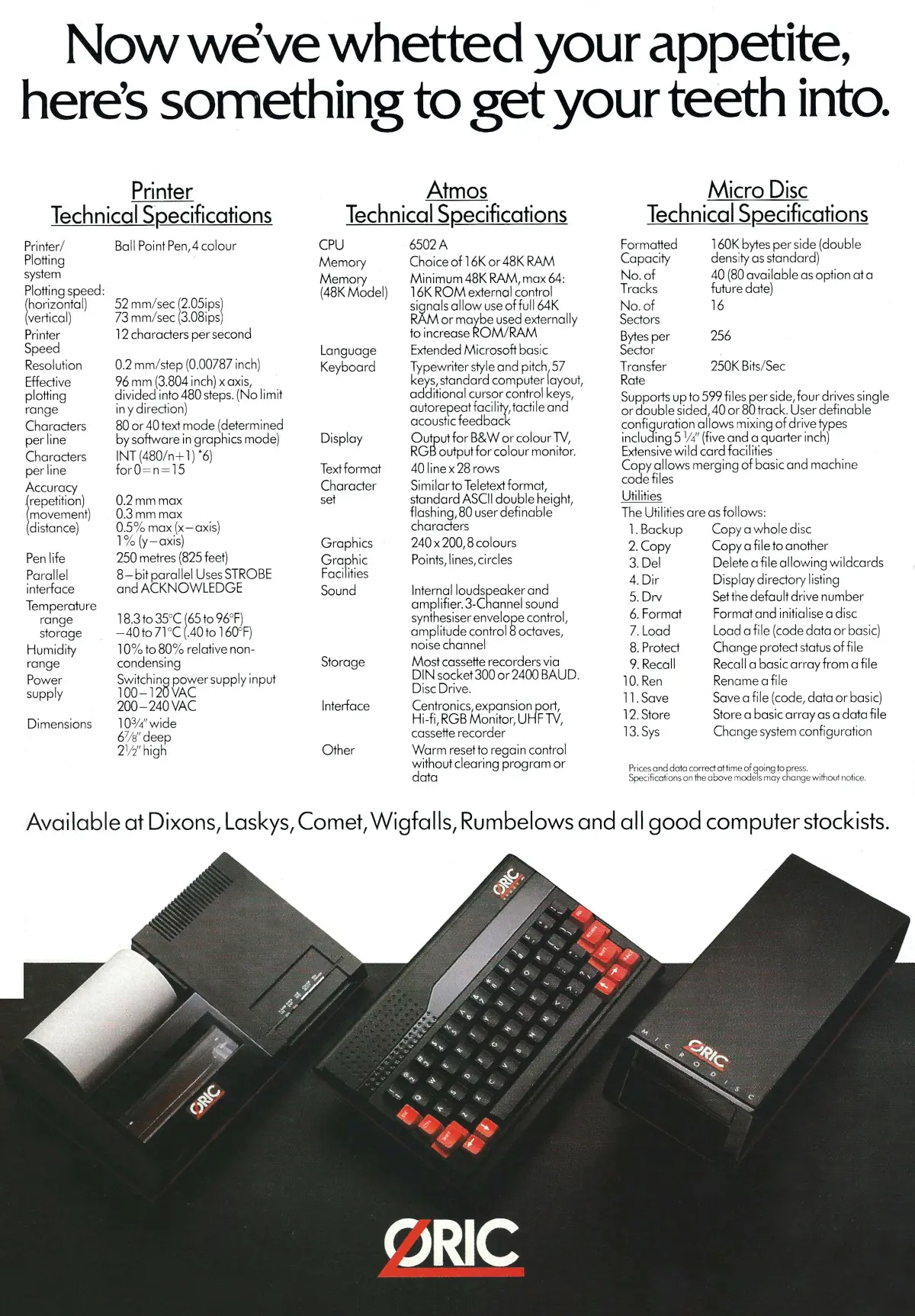

A supplement to this advert showing Oric's printer and floppy disk unit. From Personal Computer World, March 1984

Although it had poorer resolution and sound than its competitors - the Commodore 64 and the BBC Micro - it had more available memory than both.

Some of the Commodore's 64K was eaten by the system and the BBC only had 32K to start with, a full 20K of which was used as graphics memory in the highest-resolution mode.

It was quite a bit cheaper too, coming in at £170 (£740) for the Atmos compared to £400 (£1,740) for the BBC.

Oric was hoping that the Atmos would help build on the 170,000 sales of the original Oric made during 1983/84, a plan which at least worked for a while - in the summer of 1984 it was France's most popular home computer[3].

The company, did however, have a bit of an issue with a shortage of software to run on its non-standard disk operating system, which was based on Hitachi's 3" system and not the emerging-as-a-new-standard Sony 3½" format.

To counter this, Tansoft - its software arm and another reference to the old Tangerine connection - transferred several tape-based programs to disk, including business software like Oric Base and Oric Calc as well as games such as Frog Hop[4].

Tansoft advert, featuring Oric CAD and Oric Calc. From Your Computer, May 1984

Prism becomes Oric's distributor

At the same time, Prism Microsystems was announced as the primary distributor of Oric's products, which was thought to be good news at it should "ensure healthier sales of the Atmos and [encourage] a better flow of new software".

Prism had built up a good reputation for after-sales support to its suppliers and dealers, which included Sinclair, even though it had suffered a theft of 3,000 Spectrums in the previous year[5] and had lost its exclusive right to distribute Sinclair's products earlier in 1984[6].

Along with the new Oric deal, Prism also managed to secure the distribution rights for Enterprise's eponymous new computer, which was expected at the time to launch in the September of 1984[7].

The news of Prism's Oric deal coincided with an unfortunate increase in the price of the Atmos, which went up nearly £20 to £189.95, a move which it blamed on changes in the dollar exchange rate. A company spokesman explained:

"At present Oric is building up stock levels quickly in time for Christmas but the strong dollar makes the price of components high, and we have to raise the price accordingly".

Oric also reported record June sales of £2.5 million, of which £1.5 million was from France.

Only 30% of this figure, representing around 4,500 units, was thought to be accounted for by the UK"[8].

Oric sold to Edenspring

John Tullis of Oric, © Popular Computing Weekly 13th October 1983Back at the beginning of 1984, shareholders of Edenspring Investments, the property and travel investment group, had approved the purchase of Oric Products International Limited, in a take-over bid which started in November 1983.

This gave the new company net assets of £5 million to use on further development of the Oric[9] and valued Oric at just over £8 million, with Oric holding an 18% stake in the combined group, increasing to 44.2% in the event that Oric made more than £2 million in pre-tax profits in the two years ending June 1985.

The deal paid off Oric's outstanding £1 million debts and provided £750,000 in cash. Oric's chairman John Tullis said of it:

"Because we are increasing our trade so rapidly, and are going in to a number of new products in 1984 we have to widen our capital base to finance the development - we would not have been able to fund that ourselves. We have new computers and peripherals and we also have products which are not in the computer field, particularly in the area of electronic optics".

This was all part of a move to try and shift Oric's output such that computers and peripherals would form no more than 50% of its product base[10].

By April 1984, Edenspring had completed its internal reorganisation, with John Tullis stepping down as chairman "to devote more time to his other business interests", with his role being taken over by Edenspring's chairman David Duguid.

Barry Muncaster, meanwhile, became a joint managing director of Edenspring, although he was now also having to share his managing director role in Oric with the former's Peter Jones[11].

The take-over by Edenspring also meant that an Oric project to build an IBM-compatible micro was put on hold, in favour of the Atmos, at the time known as the Oric 2[12].

Financial woes at Oric

The IQ164, aka Stratos. © Popular Computing Weekly, December 1984By the end of the year there were rumours that the company had gone bust.

It hadn't yet, but its largest suppliers had become major creditors.

These including Jermyn and Hitachi (semiconductors) and Stackpole - debts at the time were thought to be around £3.5 million (£17 million in 2026).

The three suppliers were pursuaded to support Oric for at least another three months over the Christmas period with promises that sales of the Atmos would take off "like a stratocruiser" and that the Stratos - also known as the IQ164[13] - would do great things in France, despite Oric having to explain a shortage of cash and declining UK sales.

They announced in a canned statement that "the future of Oric deserves our total support, particularly in French, German, Austrian, Swiss and Italian markets" in a tacit admission that the UK market had tanked, or as Barry Muncaster put it:

"We're not very interested in the UK market at now - we don't sell in the UK, while our French market is still very strong. Our new Stratos micro is being launched in France this week [end of January 1985]. If it sells well on the continent, it will be launched here in March".

Muncaster and fellow director Paul Johnson were at the time attempting to buy Oric back from Edenspring, following their buy-back of software tentacle Tansoft in the Autumn of 1984.

Acknowledging that Oric was in a bit of a state, Muncaster reported at the end of January '85 that:

"There is a long way to go in our discussions, but we are talking to investors with the idea of putting a consortium together. We would like to tighten up Oric quite a bit. The industry is in a sticky position and we have had difficulty retaining our market share"[14].

To add to the fun, whilst this was going on Oric was also threatening former distributor Prism with a £300,000 lawsuit, presumably to get some sort of revenue coming in[15].

By the spring of 1985, Oric was really on the edge, with Bruce Everiss - Oric's marketing consultant - admitting that sales in the company's core French market had collapsed over the previous few months because, as he put it, "the Amstrad is the cult machine in France at the moment".

As well as the loss of its important Gallic sales, Oric's machines were by now being sold for £50 or less (about £200 in 2026 money)[16], whilst the company was also blaming Prism for "failing to distribute properly"[17].

The axe man cometh

After suffering repeated financial crises, the receiver was called in.

The rights for all of Oric's future machines, including the Stratos and an as-yet-unnamed Motorola 68000-based machine, as well as all existing (including partially-finished) Atmoses, were eventually sold for "several hundred thousand pounds" to French distributor Eureka Informatique, formerly known as SPID[18].

Eureka planned to continue assembling Atmoses in its newly-purchased factory in Normandy, until the stock of components was exhausted, and sell them in France because, as the company's president Jean-Claude Talar stated, the Oric still "enjoyed a good reputation [there]"[19].

It had taken several months to get to this point and there had been several companies in the frame, including the original "hot favourite" of Oric's French distributor ASN.

In any event it was expected that whoever eventually bought the remains of Oric would be paying a lot less than the £6 million of debt the company had accrued.

Barry Muncaster - geezer, © Popular Computing Weekly, September 1984Barry Muncaster, Oric's founder, had even been part of the ASN-backed £1 million bid to rescue his own company[20]. He was quoted as saying:

"You've got to be something of a lunatic talking big money. We founded Oric on £250 and we could do it all over again for £500".

Perhaps these were not the best words to fling around in the press when trying to sell a bankrupt company - even the receiver, Dennis Cross, had gone on record as being "perplexed" as to what Muncaster's status was exactly[21].

Cross had seen Olivetti's bail-out of Acorn at about the same time as Oric's crisis as evidence that "he could get a better offer for Oric", to which end he placed a new "for sale" advert in the Financial Times.

Muncaster had also caused a bit of a stir in the autumn of 1983 when he was said to have rocked up at a garage and purchased a £46,500 (£212,400) Ferrari on his American Express Gold Card - about the most expensive thing it was possible to actually put on a card, according to Amex[22].

The lawsuit against Prism never happened, and the distributor of Orics ended up as simply one of several reasons put forward by Oric for its collapse, the others being its advertising agency as well as "the stupidity of British micro buyers" - something of a bridge-burning statement if ever there was one.

As Guy Kewney wrote in April 1985's Personal Computer World, the sole function of Oric's 6502 machines - since the days of Tangerine - had been "to make other micros look better". He continued

"it was cheaper than the BBC, but what wasn't? It was better quality than the Spectrum, but everything was. It had more software than the NewBrain, a better disk system that the Commodore 64 (which wasn't hard), a friendlier BASIC than Atari, faster graphics than a TRS-80 Model 1 and better sound than an Apple".

But perhaps the biggest issue for Oric was that when other companies like Acorn and Sinclair, with its QL, were moving on to 16-bit machines, Oric had just announce a new 8-bit machine, the IQ 164[23].

Bruce Everiss of Microdigital, from Practical Computing, September 1979It was said that staff at Oric were surprised at how little fuss was being made of the company's collapse, whereas by the time it happened, most people had "taken it for granted that it would".

Before it was sold, it had amassed somewhere between £3 million and £4.5 million of debt and the future of its Tansoft subsidiary, currently in rescue talks with Bruce Everiss, was also in doubt.

Everiss, formerly of over-hyped-and-over-funded Imagine Software and before that the founder and managing director of Microdigital[24], both also of Liverpool, had left Oric - where he acted as marketing consultant - and Tansoft by March 1985[25].

Collateral Damage: the collapse of Prism

Prism, Oric's former distributor, also collapsed at about the same time.

Originally, the sole distributor of Sinclair's Spectrum (aside from a High Street deal with WHSmith), Prism had become a prominent company in the micro world as distributors, manufacturers of modems and, in partnership with Transam, manufacturers of 1984's ill-fated Wren Micro.

Only six months before its collapse, the head of one of the UK's biggest computer companies, Scicon, was even rumoured to be in the frame to take over as managing director.

Bob Denton, © Popular Computing Weekly, 15th September 1983The primary reason for Prism's collapse, as given by founder Richard Hease, was one of over-stocking in software and modems, caused in part by Sinclair's shift to direct sales.

Another ex-director of Prism also said:

"I think what went wrong was just that Bob Denton and Richard Hease had one profitable activity, which was Spectrum distribution, [but] I think they kept trying other daft ideas like the Romox software distribution scheme and the merchandising of software and robots, which didn't make money".

The robots in question included the $1,595 Topo which retailed in the UK at the same face value - £1,500, or around £6,550 in 2026 - and which was built by Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell's company Androbot[26].

At the other end of the range, Prism was also selling Movits at a far-more realistic £9.99 to £34.99.

Prism's director of developments described Movits as "The modern guy's Lego" before going on to say that "This is really a 'fun' range of robots and a lot of the entertainment and educational value comes from assembling the kit"[27].

Romox, which had been tried in the US, was similar to a scheme being trialled by John Menzies and developed by distribution companies Program Express and Micro Dealer UK.

It involved a terminal hooked up to a central computer on which customers could download any possible game on to a cassette, floppy disc or even cartridge[28].

It was also said by Hearse that he should have "stuck his nose in earlier" and not have spent all his time attending to Wren.

Wren itself had also failed to achieve success, with one of its directors giving an example of its poor financial planning:

"We bought the cheaper moulding tool and then had such problems with it that we ended up buying the expensive one too and being several months late"[29].

Prism was also faced with having to drop the price of its flagship VTX5000 modem as well as cutting staff in order to improve its cash flow.

It was also negotiating to extend its credit limit with Sinclair, with speculation floating around that Sinclair might take away its distribution deal[30] - which it eventually did when it moved to direct sales.

A month after Prism's collapse in the February of 1985, business network suppliers Modem House bought up the existing stocks of Prism's modems, including the VTX5000 - winner of Peripheral of the Year at the British Microcomputing Awards in 1984 - which it planned to sell "at special-offer prices for about twelve weeks", according to Modem House's marketing director Keith Rose.

The company, which had been a supplier of network and Viewdata systems to business, seemed keen on moving in to the home market and was undertaking to "fully support the Prism label".

It was also hoping the resume production of the VTX range beyond the point that existing stocks ran out if the current manufacturer and designer, OE Limited, was "receptive"[31].

Domino effect: OEL falls too

Unfortunately for Modem House, the near-simultaneous failure of both Prism and Oric, with which OEL was also a creditor, forced OEL in to receivership as well. OEL's managing director Martin Amsell said:

"We had a loss of revenue due to the Prism contract being withdrawn and there were bad debts from that and Oric. The company has a lot of potential but it has no time. If we had weeks rather than days we'd have a chance. [Our] existing shareholders got the jitters at the crucial moment[32]. ".

Personal Computer News pointed out that, once again, companies like OEL needed "financial backers who understand the industry".

As well as the bad debts from Prism and Oric, it was also said that a failure of a chip maker to produce a modem chip for OEL in time contributed to the company's failure.

OEL had already launched a Teletext adapter, which was being publicised on Channel Four's Oracle-based 4-Tel service.

However, there was no software available yet and so the adapter was only really useful to view, er, Oracle.

The company had also finished a QL modem, which had even been BABT approved, however General Instrument had failed to deliver the modem's central-processor chip on time, so OEL had switched to Texas Instruments for a replacement, which it delivered, but it took extra time to design which meant that OEL was bearing significant development costs with no revenue for longer than expected.

This led to lay-offs, although factory staff continued to work for two weeks without pay to help keep the company going, however one of OEL's biggest backers, a flour-making group, chose this moment to bail out, triggering the calling-in of the receiver[33].

Just before OEL collapsed, it was suggested that the company might work alongside Modem House, which was continuing to sell remaining stocks of the VTX5000 and which was "after purchasing the name and the rights to manufacture", according to managing director Keith Rose.

Whilst OEL said "no comment" to the proposed deal, the rights to Prism's assets were under discussion with Steven Adamson of Arthur Young, the company's receivers, although the possibility of a management buy-out of the Wren portable micro - a joint-venture between Prism and Transam - was "now looking pretty doubtful"[34].

The remains of Oric, with its new owners, returned just over a year later as its new Telestrat machine was launched into the UK by We Software Ltd.

The new machine - in development since the acquisition - was Atmos compatible and was specifically aimed at the communications market.

Shortly afterwards, as if to prove that the original Oric machines were still around, We Software also announced that it was running a promotion on Oric peripherals, such as the 3" disk drive for £240 (£940), a Cosmos printer for £270 (a snip at £1,050) and a V.23 modem down to £50 (£190)[35].

Oric had planned its own modem and had first advertised the £80 device in December 1982.

However, despite having claimed that it was having the finishing touches applied to it by or that it was waiting on BABT approval, the company finally admitted in the middle of March 1985 that in fact its plans to produce it had finally been shelved.

The company claimed that insufficient demand and the commitment involved in manufacture meant that it was simply not worth pursuing, but that all monies it had received so far had been refunded[36].

As if clearing up loose ends, Modem House - the company that had taken on Prism's surplus modems and which had wanted to work with the manufacturer OEL - had itself ceased trading by the beginning of 1987.

Apparently triggered by various disputes with other modem manufacturers over hardware copying, the situation was still unresolved by July, with at one point Devon CID being called in to investigate a complaint of thefts from the company made by director Keith Rose, and another against Rose himself.

The latter complaint was completed with no charges being made, whilst investigations were ongoing into the theft allegations.

Meanwhile, Rose had moved on and was now working on a "confidential communications project"[37] before apparently ending up in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight for murder and kidnap[38].

See also Tangerine.

Date created: 19 November 2013

Last updated: 28 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.