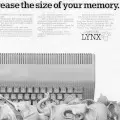

Camputers Advert - December 1982

From Personal Computer World

Camputers Lynx: How to increase the size of your memory

Camputers was formed in the winter of 1981 as Camtronic Circuits[1] - a spin-off from GW Design Services, a company that had already provided PCB design services to Acorn for the Proton[2], aka BBC Micro.

Camputers' machine - the Lynx - was initially expected to arrive in November 1982, but didn't actually make its debut until March 1983, which probably explains why this December 1982 advert isn't all "please rush me .... Lynx computers" and more "write to us and we'll tell you stuff".

The machine did, however, make its first public appearance on stand No. 269 at the Personal Computer World Show in September 1982, at a price of £150 plus VAT[3], or around £890 in 2026.

Even so, four months late was not too bad for a micro company, where being six to 18 months late was not unheard of.

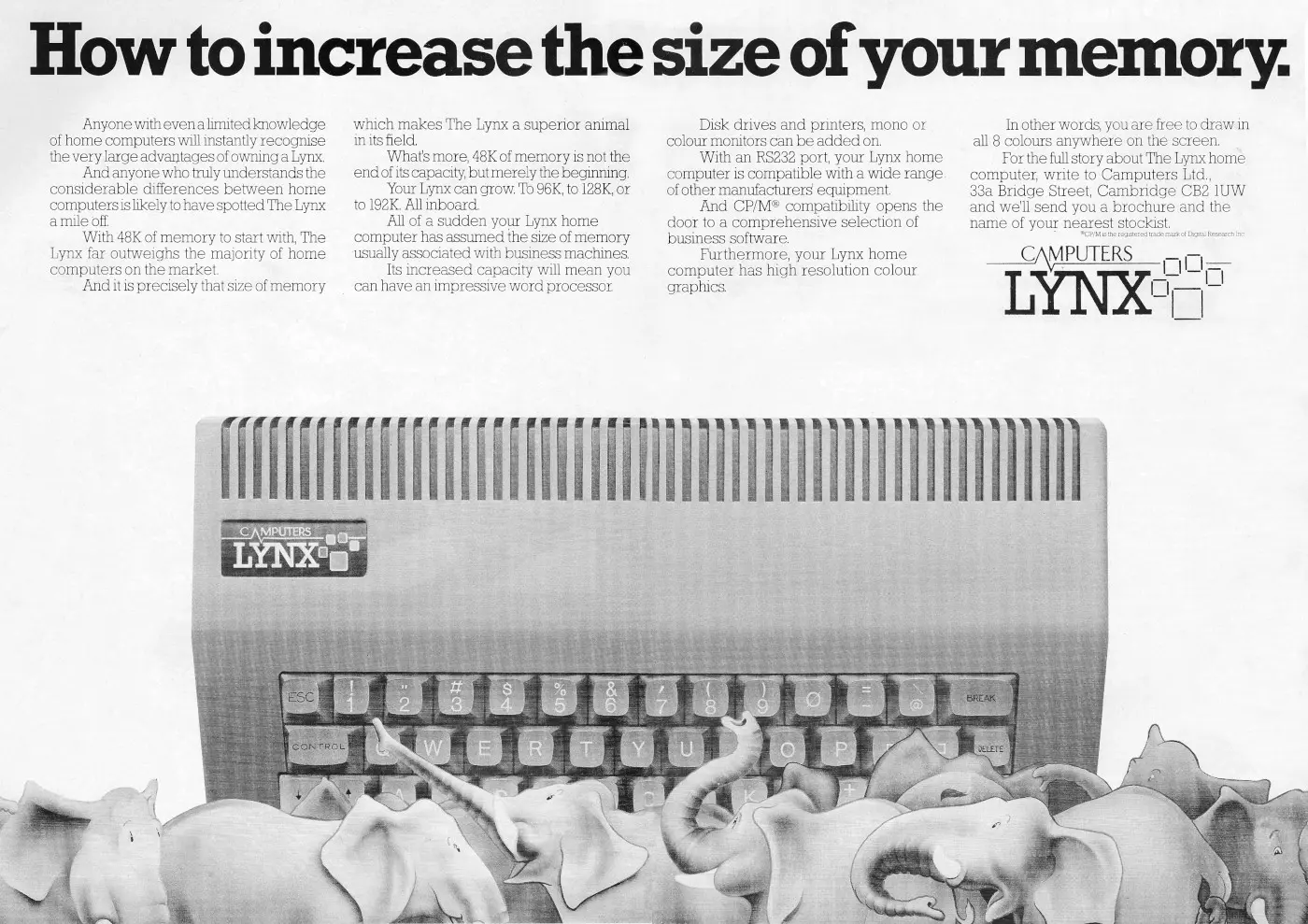

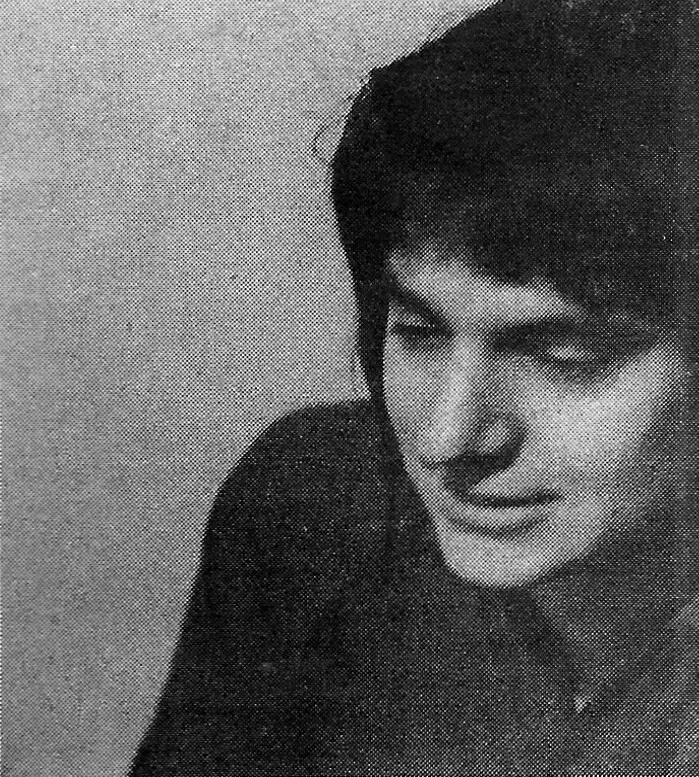

Davis Jansons, © Popular Computing Weekly, 30th September 1982The machine itself, designed by John Shirreff and Davis Jansons, was released as a competitor to the ZX Spectrum and had several unusual features, including a particularly large BASIC dialect, with the ability to run machine code in-line and an always-on high-res graphics mode.

This BASIC, written by Jansons, didn't allow multi-line statements but did have the unique and bizarre ability to use decimal points with line numbers:

10.275 print "hello"

11.666 goto 10.275

Shirreff - a self-confessed ageing hippie - had originally studied architecture before ending up at GW Design, where he had worked on a Z80-based business machine. Jansons, much the younger of the two, had previously studies mathematics before joining GW in the spring of 1982.

The director of GW, Dick Greenwood, had the idea for a low-cost micro in March 1982.

GW then conducted market research to find out where all the other micros at the time were failing, and once that had been distilled into a specification of the "ideal machine", Jansons and Shirreff were set to work in May 1982, with Shirreff on hardware. He said

"At first I sat in the garden and thought about the possibilities. Then I did a timing diagram to see if it would work. The whole design philosophy was linked to expandability - particularly now that memory is becoming so cheap. There are pros and cons with being a hardware person. I get the lead fumes from the solder, Davis gets to sit in front of the VDU all day".

The overall design process was rapid, as Shirreff said

"Once I thought it through, the actual design took about three weeks. The first prototype was completed in early July and we now have the finished product, ready for launch in late October. I suppose it has all gone quite smoothly. At least it does pretty much what I said it would".

Jansons, for his part, had been writing the machine's BASIC from scratch, with some extra contributions from Shane Voss and Fiona Miller, who provided the screen display driver. Jansons said:

"When I started I worked out I had 10 weeks to complete it - six weeks to write it and four weeks to debug it, tidy it up and make it consistent throughout. Both John and I have been working more than your standard 40-hour week - but never more than 90!"[4].

The Lynx came with a regular RS-232 port, which meant you could plug any old printer or modem in, and was also supposedly easy to expand.

After the 96K version had made its debut at the London Computer Fair and was starting to appear in the shops such as Lasky's during August 1983[5], owners could send their old 48K models back for an upgrade, although it took ages and sometimes broke backwards compatibility.

With a 4MHz-clocked Z80A, which would later be improved to a 6MHz Z80B in the 128K model, and thanks to its clever memory bank-switching system, it could run CP/M software, although the lack of available titles, especially games, was a big problem.

The promised upgrade to CP/M 2.2 never happened in the end and only around 30,000 units were ever sold, mostly into other parts of Europe.

John Shirreff, © Popular Computing Weekly, 30th September 1982One of the problems was the company's size: Camputers was very small. When it was founded it had nine employees, with GW Design Services adding a further sixteen. They had to seek out subcontractors to actually build the machine that they had designed.

The aspirations of Dick Greenwood - one of the other Lynx designers - that the company could sell 40,000 units in the following year alone[6] - proved to be a bit optimistic, not least as it would be nearly another year before the machine finally saw the light of day.

When the Lynx was finally made available to the press for review, Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World wrote that his first Lynx

"exhibited so many pre-production oddities that I suppose it wouldn't be fair to report them, because Camputers promptly took it back and produced another".

A spokesman for Camputers explained that

"The fact that it won't automatically switch your tape recorder on and off is due to the fact that the wires to the switching transistor from your tape are back to front. You will have to replace the transistor with a relay circuit"[7].

In the summer of 1983, Camputers set up a new company - Camputer Holdings PLC - offering some 25% of Camputer's share capital for sale to the public.

The intention was to raise £900,000 in order to fund the company's expansion and development of new models, with Camputers keen to encourage smaller investors, even though the minimum purchase of 3,000 shares at 17p per share worked out at £510, or around £2,330 in 2026.

At the time, Camputers was forecasting a profit before tax of around £750,000 for the year ending March 31st 1983[8].

Camputers Limited, based on Bridge Street in the heart of Cambridge, went bust only a year after that, in common with many others in the great computer-company shake-out of 1984/85.

"Your Computer" magazine predicted something along those lines when it said

"The Atari [800XL] and Commodore [64] machines ... have large libraries of quality software. If Commodore can quickly overcome the current reliability problems of one of its products and Acorn is able to manufacture the Electron in large numbers, life will be very difficult for the Lynx[9].

Commodore itself, sitting on assets of £330 million, was also forecasting the great shake-out when it predicted at the end of 1983 that "Eventually the number of computer producers will be reduced to a handful of companies"[10].

Not long before it went bust in the summer of 1984, Camputers had announced its next machine - the Laureate - but the company had been looking for additional sources of finance for some time, with no luck.

As reported in July's Your Computer: "it now appears [Camputers] have reached the end of the road with liquidation as the most likely outcome".

Dragon Data was in similar financial difficulties and the news of both companies' woes was said to have sent a tremor through the micro business.

The timing of this all seemed particularly unfortunate as figures released by market-research company AGB Home Audit showed that micro sales in general had increased 75% year-on-year in the first quarter of 1984, which represented shipments of about 200,000 units[11].

This success, however, would come back to haunt the micro industry as in hindsight this was simply a final surge as the market reached saturation.

Sales collapsed at the end of the year and the home computer boom was all but over.

Back in 1980, Practical Computing had predicted that there would be 300,000 computers in the UK by the end of 1983, but as it turned out by the spring of 1983 a million micros had been sold[12].

The problem was, as Boris Allan accurately posited in the Ziggurat column in Popular Computing Weekly in November 1983, that the growth curve would turn out to be a Logistic, or Sigmoid, curve - a type of curve often associated with populations or demographics.

The properties of this type of curve suggested that early on growth would be slow - which it was - as its curve was a function of "the more people there are with a computer, the more likely it is that a person without a computer will buy one", and early on there weren't that many.

Then, the graph steepens, and in the mid-point of the home micro industry's curve - around 1982 to early 1983 - growth looks explosive.

More micro manufacturers and those dependent on them, like software houses, peripheral manufacturers and magazines, pile in to exploit what looks like ever-increasing demand.

Unfortunately, any market reaches a point where "anyone who might want a thing has a thing", and all that is left is replacement and upgrading - it's still a market, but one with little or no growth. As Allan pointed out:

"the market for cheap introductory computers is about to decline. Any new manufacturer with a low-cost computer has no chance at all, and most of the later manufacturers of cheap computers seem to be on a knife-edge"

Allan also suggested that Sinclair and Commodore seemed somewhat safer, before continuing:

"Everyone seemed to behave as if the then-projected (and inaccurate) growth rate would continue indefinitely. Companies are now fighting, ever more fiercely, for a share of a smaller cake. And the number of casualties is rising"[13].

It's all very similar to how the tablet market flattened and then declined from 2015[14][15] - although it did pick up again after 2021[16].

An editorial in the same magazine the week before had also touched on this theme, suggesting that home computer manufacturers were running scared, noting Atari's $536 million three-quarter loss, TI's dropping of its TI-99/8 micro amidst massive losses, Mattel's dropping of its Aquarius and market exit and even Apple's problems with its ludicrously over-priced Lisa. As Brendon Gore wrote

"The image of the micro industry as a golden egg-laying goose is looking distinctly tarnished. It is no coincidence that the shares of Acorn were not exactly over-subscribed with the company joined the Unlisted Securities Market earlier this month".

Gore also suggested that City of London investors were "considerably more wary about the prospects for micro companies than they were a year ago" and that "it will be interesting to see which companies are still around in a year's time"[17].

Despite the death of Camputers, there were clearly enough interested users around to warrant a Lynx User show in Birmingham at the end of March, 1985.

There were even new peripherals on display, including an RS432 unit, trackball, "sideways" ROM, speech synthesizer and CP/M software.

A sort-of self help collective, the Lynx User Group had permission to develop the 48K and 96K models, whilst the newer 128K was being looked after by Anston Technology[18].

Plans were afoot to even update the ROM BASIC, improve manuals and work on the graphics, for which it was felt there was "enormous untapped potential buried in its depths".

Anyway, the 96K Lynx retailed for £299 (about £1,360 in 2026) whereas the upgrade, which included an extra 4K ROM, was available for £89.95 (£410 in 2026).

The 48K Lynx had been retailing at £225 (£1,020) since its launch in 1983.

At that time, the 48K Spectrum was on sale for £50 less than the Lynx, which was considered a reasonable difference given the better keyboard, graphics and built-in machine-code monitor included with the Lynx, but by 1984 the Speccy had dropped to £130 (£560) whilst the Lynx stayed the same.

This probably didn't help.

Date created: 01 March 2013

Last updated: 15 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.