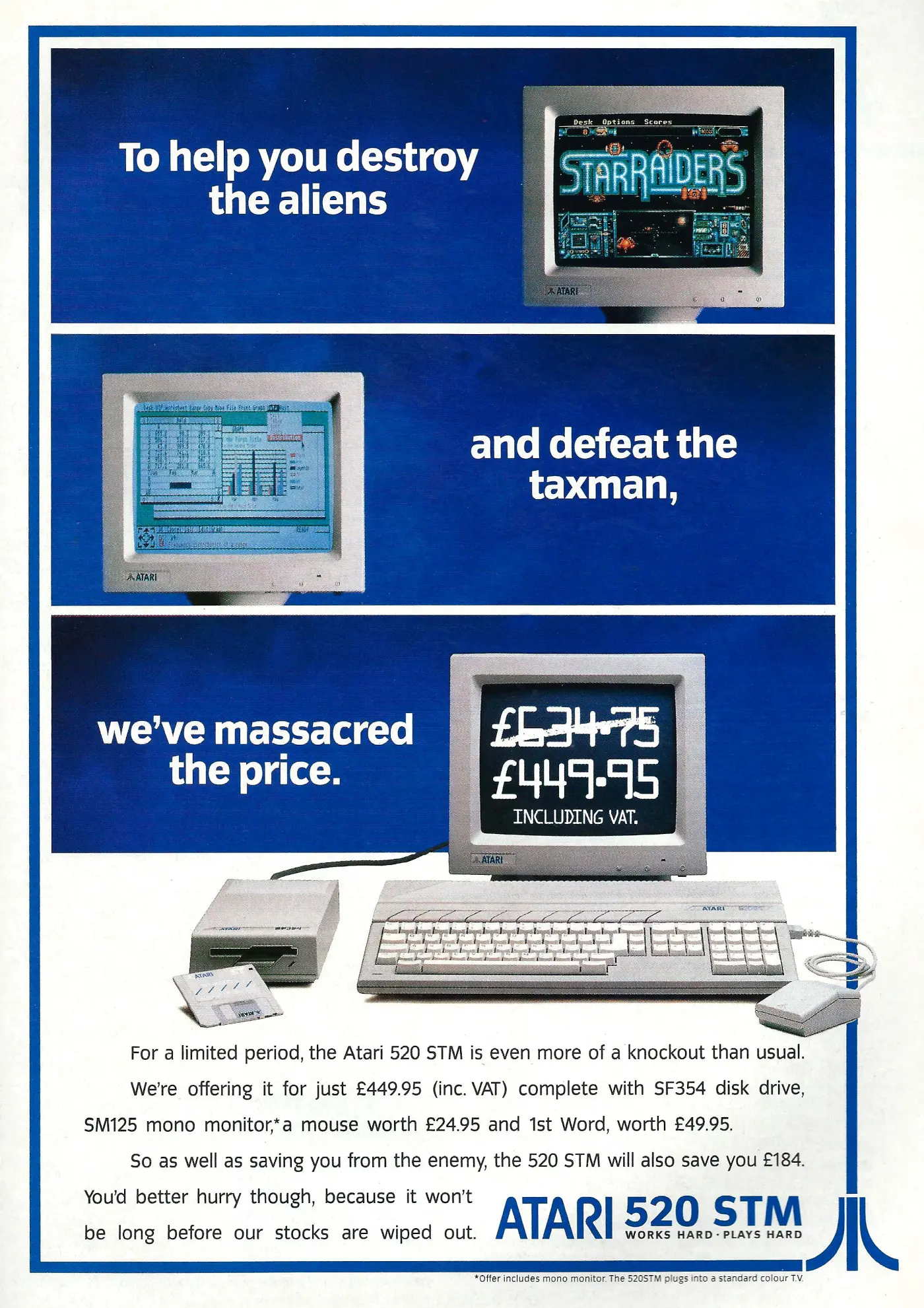

Atari Advert - June 1987

From Your Computer

Atari 520STM: To help you destroy the aliens, we've massacred the price

The Atari 520STM was fundamentally the same machine as the previous ST model, except that it came with a built-in TV modulator and had its OS and GEM graphics manager supplied in ROM.

The "special offer" retail price of £450 (around £1,650 in 2025) included the external floppy drive and mouse, together with the word-processor package "1st Word".

The use of a TV via a modulator as a monitor - without a TV licence - got a boost within a year of the STM's launch when the UK's Home Office clarified its position on the issue, stating that "If a television set is used solely as a monitor in conjunction with a home computer or video game machine, a [TV] licence is not required".

That was as long as anyone visited by the TV detector van could provide that they hadn't received broadcast television on it[1].

Jeff "yak" Minter, © Your Computer December 1987The STM had been launched in the UK at the first Atari Computer Show at the Novotel in London, along with Atari's return to games consoles in the shape of the £70 7800.

Also there was software legend Jeff Minter, once a Commodore stalwart until switching sides upon the advent of the original ST, who was there to show off his recent creation - a software lightshow called Colourspace[2].

However, within a year of its launch, the STM's future was already in doubt thanks to the release of the STFM ("ST, Floppy, Modulator), which with a planned price cut in September 1987 to £299 would take it to the same price as the non-floppy STM.

An advert for Yak's Progress - a collection featuring eight of Minter's ruminant-themed games, including Metagalactic Llamas Battle at the Edge of Time, and a version of Colourspace for the BBC Micro. From Commodore Horizons, December 1985

At this point it was thought that 45,000 STs had been sold in the UK, but this was set to increase with the signing of High-Street retailers Dixons and Comet[3].

This move came quite some time after Atari had announced that it was opening up its distribution to include mass market outlets in the US.

This particular move, in the spring of 1986, would however leave its previous speciality computer shops with the new 1040ST, whilst the 130ST and the 800XL were quietly dropped.

Also announced was the fact that Atari had sold over one million video game systems in 1985, and that it was resurrecting its plans for the 7800 - an Atari 800 in a different box - with an expected retail price of only $80.

The venerable 2600 was due to be updated with a more compact form-factor, and the company reckoned that it still had "several good years of life" left in it[4].

There were however worrying signs of complacency, as whilst the ST appeared to be taking over the world, it was also said that the company was in something of a deep sleep, especially when it came to its relations with software developers.

Commodore had been having severe financial problems, which led to it negotiating a $150 million overdraft in order to stay afloat. This contributed to the company failing to invest money in developing and selling its Amiga, and helped give Atari a head start.

However, Guy Kewney, writing in May 1986's Personal Computer World, sugested that Atari had "solved" many of Commodore's problems, not through money, but by ducking them. he wrote:

"The machine wasn't ready, so they shipped incomplete STs. The software was in pre-Beta release versions, but they shipped it anyway. And when you opened the box, you found that things that were supposedly included in the price (like BASIC) weren't there. If you asked Atari why not, it just lied. Atari said it was there, honestly".

This created enemies among software developers, with the situation leading to Sig Hartmann - Atari's head of software and formerly at Commodore - having to apologise to assembled programmers at the Atari Show in London earlier in 1986, saying:

"We'll try to improve communications with you, and we thank you for your patience".

Lack of early machines had led to programmers in the US developing on Apple's Macintosh - a "difficult beast to control" - whilst those in the UK had been practicing on Sinclair's QL. Both these machines used similar CPUs to the ST, but the QL was much cheaper and more accessible.

The head-start meant that there were lots of UK software houses on the Atari stand for 1985's Personal Computer World show, but by early 1986 Atari was suggesting that the proportion of US-written software far outweighed the UK stuff.

This seems to have boiled down to the lack of support from Atari in the UK for its developers, with one UK programmer saying:

"Our program is out, but we couldn't have done it through the UK support people, because there weren't any. We had a direct-line number of a systems writer in Sunnyvale, California[5]".

Towards the end of 1986 it had been rumoured that Atari's Jack Tramiel wanted to buy back his old company - Commodore - in order to secure access to the Amiga's follow-up chips, then currently in development.

Atari already had an active lawsuit attempting to establish that the Amiga's chips belonged to it, a position based on the fact that Atari (before Tramiel) had invested £500,000 in Hi-Toro, the company founded by former Atari employee and chip developer Jay Miner, in order to help it develop the chips for their new "Lorraine" machine - chips which Atari was interested in.

The "Lorraine" machine would become the Amiga but the company needed more investment to bring it to market.

This investment was supplied when Commodore unexpectedly bought the company, whereupon it almost immediately cancelled all existing contracts, included the one with Atari.

The worry, for Amiga fans at least, was that if Tramiel managed to oust Irving Gould, the enigmatic Canadian financier behind Commodore who toppled Tramiel in a boardroom coup, and buy back Commodore, he would kill off the Amiga and put the new chips in the Atari ST instead[6].

The 520STM had been around since the summer of 1986, where it was on special offer during June and July in four "cost-cutting bundles", for example with a disk drive down from £548 to £499 (£1,890 in 2025) or with a monochrome monitor at £699 (£2,650) down from £846.

Atari UK's marketing manager Rob Harding said of the deals, somewhat uninspiringly, that "the packages would appeal to a broad base of users"[7].

There were continuing rumours of prices cuts from the beginning of 1987, although perhaps not quite down to the £199 price point that some pundits were suggesting.

Atari UK Managing Director Bob Gleadow was denying such drastic cuts, but did point to competition from Amstrad as a reason for a price trim, saying that the Brentford Boys had "created a price perception at £399"[8].

The Inmos Transputer

Gleadow, former general manager of Commodore UK and who had not that long ago served time out at Commodore Electronics Limited - the Hong Kong branch of which was the Commodore equivalent of being exiled to Siberia - had his hands full by the end of 1987.

He was trying to dampen enthusiasm over the Atari CD-ROM unit and the next generation of Atari micros, which were rumoured to feature British Transputer "wonder" chips, both of which were announced at the Personal Computer World Show.

The Transputer - a portmanteau word combining Transistor and Computer - was a radical new parallel-processor architecture developed by Inmos of the UK, a company which had been set up in 1978 "to counter the drift of semiconductor technology away from the UK"[9].

It had been promoted by MP Tony Benn and funded by the National Enterprise Board - the same NEB that had part-nationalised Sinclair in the late 1970s.

Atari's Transputer machine, which was thought to have started under Gleadow's influence[10], ran the Inmos T800 which had a 32/64-bit architecture, ran at 15 million instructions per second (MIPS) and supported 16 million colours.

Atari's ST processor, the Motorola 68000, clocked in at around 1.4 MIPS when run at 8MHz[11].

Later on there were rumours that Atari was possibly in the market to buy Inmos outright, which by 1987 was owned by Thorn-EMI.

By 1988, Thorn - which never seemed happy with its acquisition and which had long been openly seeking a buyer or a major partner - was coming in for some flack as it didn't seem to be exploiting its world-beating Inmos subsidiary, even though more than half of the US' SDI "Star Wars" projects were apparently built around the processor.

Companies like Real World Graphics were also building graphics cards around the chip that could do unheard-of real-time full-colour 3D graphics manipulation[12].

It was perhaps unfortunate for Thorn that it announced that its "flagship" Transputer was finally coming into volume production in the same week as it announced that revision C of its T800 chip was faulty[13].

The news didn't get much better for Inmos, which by the end of 1988 was owned by SGS-Thomson[14], even though sales had improved on its bottom-of-the-line T400 processor following a price cut down to only $20 per chip.

The company seemed to have finally realised that it needed memory management built in to its chips in order that Unix could be more easily ported to it, at a time when there was suddenly a lot of competition for the Unix market in the form of HP, Intel, Mips, Sun, Pyramid and even Acorn's RISC chip - the ARM.

And, as Guy Kewney quipped in November 1989's Personal Computer World, the competition had the "significant advantage of not being Inmos".

Inmos's previous dabbling in the computer graphics market came in handy towards the end of 1989, when IBM launched the VGA graphics system in its PS/2 range of microcomputers.

This was based around a prototype built by an Inmos engineer as a design exercise to create a chip which could do fast colour look-up tables.

The sale of this chip, which the company itself didn't even really know it was developing, netted it several millions and gave it a much-needed boost of confidence[15].

Although there was a suggestion that a 50-Transputer system could theoretically run Unix, the big problem was that Inmos's potential new general-purpose processor - codenamed H1 or HUMPS 1 and announced in September[16] - which would really make it viable, was a full 18 months away.

This put any real availability into 1992 - and a lot was likely to have changed by then[17].

When the first Transputer was announced in 1984, it was said to have the speed of a VAX minicomputer, which was about ten times the speed of the average PC at the time, but by the end of 1989 the performance of chips like Intel's 80386 had more-or-less caught up with that of Inmos's T800.

Nevertheless, the Transputer's floating point performance was just ahead of a high-end maths co-processor at around 2 MFLOPS (2 million floating-point operations per second).

Despite the apparently narrowing performance gap, it was still true that in a multiple configuration it should still be possible to build the fastest supercomputer in the world.

Although the specs for Inmos's new H1 were still hazy, but Inmos was aiming at 20 MFLOPS and 10 million instructions per second, or ten times the performance of its T400[18].

Elsewhere, some other multi-transputer computers were making an appearance, including an Ethernet Transputer Server from Unsworth's U-Micro, a name previously associated with the 68000 world.

Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World was not too enthusiastic about the machine's "piffling" £20,000 price tag for an 8-Transputer system - that's roughly £70,300 in 2025 - although that was still good value compared to the "less feeble" 64-Transputer server, which could be had for a snip at £120,000, or around £422,300 now[19].

Customer un-support

Rumour and speculation aside, there was a lot of activity surrounding the transputer.

Unfortunately, Personal Computer World reckoned that Inmos was simply incapable of adjusting to this brave new world where it was actually popular and in demand, as it seemed unable to manage its end-user support.

The company had set up a conference on the US Compulink Information eXchange, or CIX, through which it was offering support to its customers - not just the then-best-known Transputer company MicroWay, with its MultiPuter, or Perihelion/Atari, but also hundreds of smaller projects said to be on the go around the world.

An advert for Compulink Information eXchange, or CIX, via its Surbiton, UK, office. From Personal Computer World, June 1989.

However, having to deal with fraught users facing difficult problems proved too much for the thin-skinned company, and so it pulled its CIX conference after a matter of weeks.

In that short time it had managed to accuse MicroWay of competing with it, claimed that the head of the Transputer User Group was encouraging users to subvert Inmos's copyright, and had told several users that "it wasn't there to be insulted"[20].

Date created: 06 November 2019

Last updated: 11 December 2024

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2025. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.