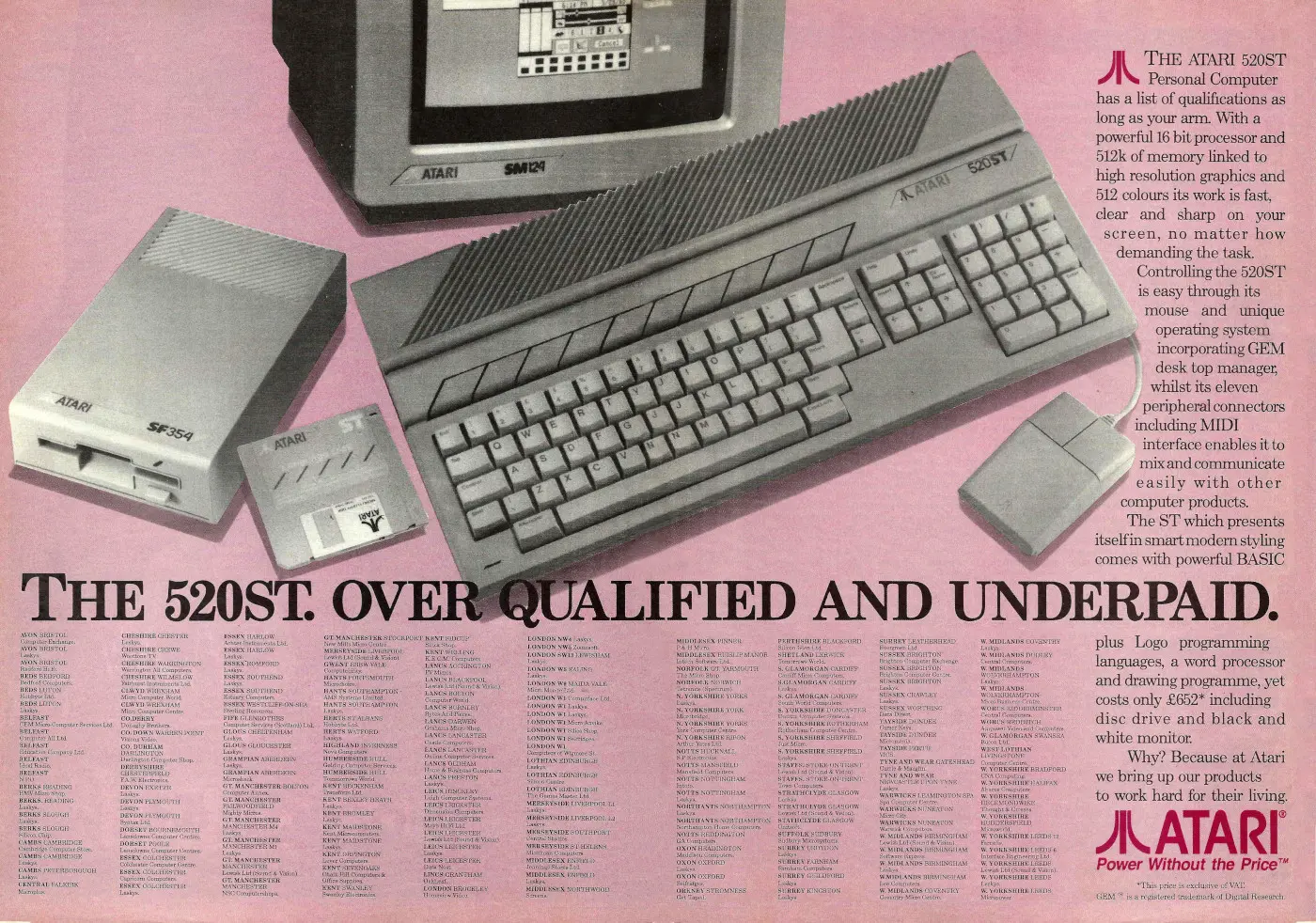

Atari Advert - April 1985

From Your Computer

The 520ST. Over-qualified and under-paid

After resigning from Commodore in January 1984 - the business he founded as a typewriter repair outfit in the 1950s, and the company that produced the world's first all-in-one "personal computer" the Commodore PET in 1977 - Jack Tramiel formed Tramel Technology Limited with his sons.

The missing "i" from the new company's name was an attempt to get the pronunciation of the name closer to that of its native Polish Trzmiel - something like Tsh'myEl.

For a while Tramiel dabbled around with various things, for example using $671,000 of his personal fortune in the summer of 1984 to buy 113,000 common shares of Adac Laboratories - a medical device company based in Silicon Valley, California[1].

This increased the Tramiel family holding to around 6.5%, with Tramiel Senior expressing "an intent to seek representation on the Adac board of directors and expect to be more than passive investors"[2].

Tramiel buys Atari

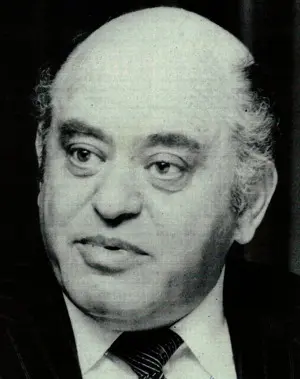

Jack Tramiel, © Home Computer Weekly, December 18 1984Shortly afterwards Tramiel surprised everyone when he purchased the struggling Atari Consumer Electronics division from Time Warner.

Atari, incorporated on June 27th 1972, got its first break when it launched the early and successful video game Pong.

It went on to launch the VCS/2600 console which was hugely succesful and came to define the video-game console industry during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

However the company had to be sold to Warner Communications in 1976 in order to raise the finance to produce it[3].

Atari suffered a catastrophic fall in the early 1980s after the market became saturated with me-too machines, poor-quality games, and increasingly-capable home computers, and it became a major financial headache for its parent company having lost nearly $540 million in 1983 alone[4].

The fire-sale of Atari enabled Tramiel to buy it by assuming its debt at below market rates, rather than paying any cash[5]. Warner was said to have "sold Atari to Jack and loaned him to money to buy it"[6].

This seemed even more true within a year following the sale, when Warner Communications wrote down the $240 million still owed by Tramiel down to $135 million, whilst also buying over $10 million of Atari's customer credit, loaning it $8 million and promising an additional $4.5 million later[7].

Speculation about an Atari sale had been going on since at least the end of 1983, when Australian media magnate Rupert Murdoch purchased a 6.7% stake in Time Warner, for $98 million.

Murdoch was said to be anxious to dump Atari, not just because of the obvious problem of its loss making, but also because Murdoch's interests were clearly elsewhere in Warner's film and TV operations.

It was thought that no US company would be interested either, having seen what happened to Texas Instruments, Mattel, Osborne and the rest. Popular Computing Weekly suggested that it was:

"Extremely unlikely that anyone will be able to turn Atari round and start making a profit - at least not in the short term".

It was even thought that Atari could be sold off to a European manufacturer keen to get access to the US market, with both Thorn EMI and MV Phillips being mentioned[8][9].

The plan to gain control of Warner Communications continued in to early 1984, when Murdoch indicated his intention to take his stake up to 49.9% - a move that required an additional $900 million[10].

Atari is restructured

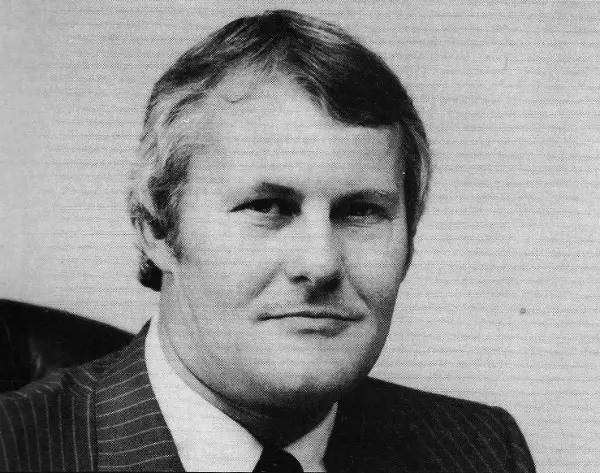

Graham Clark, former Atari UK managing director, © Popular Computing Weekly, 26th July 1984Upon taking on Atari, Tramiel declared that "too many people have become fat out of this business" before slashing the price of the then-current 800XL to £129.99 (£540).

He also scrapped the 7800 games machine - the heir to the 2600 and which had been launched only a few months before[11] - and laid off 9,000 of the 12,000 workforce.

The end result of closing factories and streamlining operations together with an investment of $150 million to turn Atari around was Tramiel's desire "to pass the savings on to the customers"[12].

The longer-term aim was to become a billion-dollar-profit company, with particular high hopes for the European market, whilst Tramiel derided the lack of competition in the market by saying that

"If someone is producing better computers than me at a lower price then people will buy them".

In the UK, the effect of the Tramiel take-over was felt within weeks, as first Atari UK's managing director Graham Clark resigned and was swiftly replaced by the company's financial controller, Simon Westbrook.

Many of Atari UK's sales and management staff were sacked - largely as Atari was shifting to selling through distributors rather than maintaining its own in-house sales force[13].

Enter the Jackintosh

Tramiel's defining project at Atari was the Atari ST - not apparently standing for the initials of son Sam Tramiel but Sixteen/Thirty-Two[14] - a reference to its CPU architecture.

It was also known, at least in the UK press, as the "Saint", and elswhere as the Jackintosh or Jacintosh[15], in homage to its perceived role as a competitor to the Apple Macintosh - a perception based solely on the fact that the two machines shared the same CPU and a similar-looking user interface.

The ST was a machine that caused considerable surprise on its UK unveiling during 1985's Personal Computer World show.

For a cynical market used to vapourware and over-optimistic promises, the ST seemed to arrive fully-formed, with 3.5" floppies, a massive (at the time) 1MB of memory and already over 50 software packages running[16].

This was a feat all the more impressive because Atari had designed, built, tested and got a working machine out of the door within only six months[17].

Tramiel himself spearheaded the launch on the show's opening day with the claim that the ST introduced another revolution in computing. He had said at the machine's US launch that

"We're in the business of People's Technology. And as Henry Ford said, for every dime you remove from the cost, a whole new stratum of buyers is revealed. I believe it, and that's how this business is going to be from now on"[18].

Tramiel had previously flown in to the UK at the beginning of December 1984 to outline Atari's forthcoming plans with its new machines, which as well as the ST included a re-vamp of its existing 8-bit line.

Echoing his famous Commodore catch-phrase of "for the masses, not the classes" he pointed out that the ST would not be compatible with either IBM or Apple and that TOS was a proprietary system before continuing:

"I do not compete with IBM. I make PCs for the masses, and leave the business side to IBM".

He also claimed that Atari was on course to break even by the end of December 84 - a remarkable turn-around from its recent $10 million-per-month losses - and that he had settled 85% of outstanding creditors' claims since the June '84 take-over[19].

Tramiel expanded on his point of view about the business market in an interview in April 1985's Practical Computing by saying:

"I will be selling it through individuals, and if any business is smart enough that they want to come and buy it from our dealer, they will be welcome. We will not have a business division, as such, trying to concentrate on the Fortune 500 [companies]"

He also expressed an interest in the educational market, which was largely owned by Apple in the US, where it offered discounts to schools and colleges for its hardware. Tramiel continued:

"We will definitely have special schemes for schools, but we don't need to do the same thing as Apple, because the Apple discounted price is twice as high as our normal price. It will be at all three levels of education[20]".

Power without the price

The "Saint", sold under the tag line "Power without the price", was a Motorola 68000-based machine (the 32-ish-bit CPU as used in the contemporary Apple Macintosh) with high-resolution graphics, a large 192K ROM and a whole load of ports.

Perhaps the most significant of these was the ST's MIDI port, a feature which ended up making this machine very popular with home musicians.

It also used the Graphics Environment Manager (GEM), developed by Gary Kildall's Digital Research[21], the company which had written the de-facto industry-standard business Operating System of the 1970s and early 1980s - CP/M - which was later "borrowed" by Microsoft[22].

GEM, which Tramiel said was "easier to use than explain", ran on top of an operating system based upon Digital Research's CP/M-68K and which was known as TOS, for "Tramiel Operating System".

However, by 1986 Atari was denying that this was what TOS meant, instead suggesting - perhaps implausibly - that it stood for "The Operating System"[23].

News that Atari might offer other operating systems, with one of the alternatives being called Jason, would normally have been considered as just another example that Jack Tramiel "had all the angles covered", but given the fragile nature of the micro industry at the time it caused some concern that TOS wasn't "as complete as they'd like you to believe"[24].

Even by May of 1985, GEM was still being debugged and refined on disk for the 520ST, with "no question of putting the operating system on ROM" which was seen to be vital for the success of the diskless 130ST.

It wasn't until March 1986 that the operating system was finally release on ROM - buyers since the beginning of the year had been getting ROM upgrade kits, whilst those who had bought their STs the year before could stump up £25 for the privelege of not having to load their operating system from disk every time they started up their machine[25]

There was also some concern that the relative rarity of 68000 programmers might affect the success of the machine. Popular Computing went as far as to say

"Quite simply, there aren't enough people who can program the 68000 to a high-enough standard to produce a software base that would compete with, say, that on a Spectrum".

The sentiment was directed towards the lack of software for Sinclair's QL, but the two machines shared the same processor, more or less.

An industry in crisis

The 520ST was launched during an era of industry crisis - Commodore had announced a drop in sales for the first time ever, Sinclair had delayed its flotation, Acorn had been bailed out by Olivetti in the summer, and many others, like Dragon and Oric, had already called in the receivers.

The industry gloom was summed up nicely in a review of Comdex Fall, held in Las Vegas in November 1985, in January 1986's Personal Computer World, which reported:

"Loss of confidence in the micro industry cast a shadow over the seventh annual Computer Dealers' Exposition and Conference - Comdex/Fall 85 - when it opened its doors in Las Vegas on 20 November. The number of exhibitors was down from last year's record, the number of visitors was down, and the main conference speech was called 'Surviving the Industry Downturn'".

Whilst there were a few Amigas to be seen around the show, Atari ended up being the sole home-computer manufacturer to exhibit, after Commodore had pulled out at the last minute.

However, its stand was full of third-party software houses, so at least some things were looking up[26].

That all helped the ST to buck the trend and be one of the last hurrahs of "independent" (as in not IBM PC-compatible or Apple) computers of the era, along with arch-rival Commodore's Amiga and Amstrad's PCW.

The machine trickled in slowly: at the beginning of May 1985 there was though to be only one machine in the UK and a dozen in West Germany, although 200 $4,500 (around £12,400) development machines were due by the end of the month.

Market-ready systems were expected before the end of summer, however these early machines, like Commodore's Amiga, would be supplied with disk versions of their software, including GEM, so that "last minute 'features' can be corrected".

They were so rare at the time that the machine Personal Computer News got for a benchtest had been previously used by none other than Sam Tramiel, son of Jack, and had the sticker to prove it[27].

Tramiel obviously expected to rectify this shortage, as on a trip to England in March he was said to have promised to:

"Manufacture a million computers this year, minimum. That may sound a lot, but at the last company I worked for we were making 400,000 a month"[28].

Atari cancels more models

There was, however, some confusion at first as to exactly which models were going to be launched.

Atari had announced eight potential models in the December of 1984, but by April 1985 it was confirmed that several of the models had been canned, including the 65XEP portable, which was cancelled in March.

Also gone was the 65XEM, as its only extra feature was MIDI and that was something the newer ST could do, and the 65XE, a 64K version.

The cancellations largely reflected the rapidly-changing market at the time, or as Atari UK's managing director Simon Westbrook stated:

"While the idea of an 8-bit portable seemed excellent in January [85], the 16-bit looks a better bet now. With chip prices tumbling and needs becoming more sophisticated, we reckon 130K and 16-bit will become the norm, and we don't need to be messing around with 64K in music machines and portables. At CES in January, however, the difference in cost between a 64K and 130K was far more substantial"[29].

By May it was thought that even the XE130 wouldn't appear, meaning that none of Atari's new 8-bit machines would actually be launched.

Also thought to be gone was the 128K model of the ST, the 130ST, which was shown at the winter CES in Las Vegas, as well as the 256K 260ST.

US product manager Richard Frick said that there would only be one model of the ST shipped "because it doesn't make any sense" to see a smaller version. In the UK, local sales and marketing manager Rob Harding said:

"We are still looking at possibilities for other ST machines. It depends on which machine we decide to put in the £400-£500 price bracket".

General manager Simon Westbrook pitched in with the observation that:

"It might just be that other models might come in above the 520ST".

Atari's dynamic approach to its range, and its willingness to drop models rapidly if they were no longer technologically viable, was very much a reflection of Tramiel's philosophy, where he said:

"I always believed that micro-computers were technology-driven not marketing-driven. You always have to be your biggest competitor. Try to make every time a better product to compete against yourself. Never fall in love with the product that you have right now, but if there is better stuff out there, make it[30]".

Meanwhile, the 520ST's launch had been delayed to July in the US, even though Atari had said at CES that the machine would be available from April.

The delay was not expected to affect the UK launch, although the package changed with Rob Harding saying that:

"The ST will now be available with both a disc drive and a monitor bundled with it in late May or early June".

Initially, supply was expected to be very restricted, with many of the few machines available going to software houses, with what was left going to retail.

By June Atari was claiming that over 100 UK software houses were developing on the ST, with a third of its machines going to business software companies including Psion, Precision and Triptych, a third to utilities and the remainder to entertainment software houses[31].

Atari was also having some issues with distributors, with several announcing that they were bailing out of Atari hardware.

Terry Blood of TBD blamed this on Atari's "unworkable formal distribution agreement" which Blood called "commercial suicide".

This agreement, according to Dave Woods of fellow distributor Lightning, included having to take on the entire range if a retailer wanted to sell just one model.

Atari's Harding justified the move by saying:

"We expect distributors to be our business partners and that means they take all our products - in depth. We do not want them to use Atari as a warehouse"[32].

The 520ST is launched in the UK

The 520ST was finally launched officially in the UK at the Personal Computer World Show, Olympia, between the 4th and 8th of September 1985.

The company took a large stand in particular to accommodate the 50 520STs (and one 260ST) it was showing as well as around 50 third-party software companies that were exhibiting software for the 520.

Atari was still suggesting that the 260ST would arrive in the shops before the end of the year, possibly even October.

The Atari CD-ROM player - shown at Summer CES in the US and the first ever for a home system - disappointed some by its non-appearance, but it was still hoped it might be in the shops in time for Christmas.

Atari UK's sales and marketing manager Bob Harding blamed its absence on the fact that it was "with software developers at the moment"[33].

The appearance of the 520 at the show marked the start of real availability in shops, as Atari was ramping up its production[34].

Also ramping up was third-party software, with Atari announcing a list in September of some 170 software titles currently under development for the 520ST, with many expected to run on the cut-down 260ST[35].

Also included in the list was Metacomco's series of programming languages.

Metacomco was the Bristol-based company that was instrumental in producing the AmigaDOS operating system for arch-rival Commodore's Amiga and which had won the prestigious Supreme Champion 1985 at the South West Export Awards, as sponsored by Bristol Chamber of Commerce and now-defunct Harlech TV amongst others[36].

Whilst Tramiel, a man said to be a symbol of US enterprise "not only because he's predatory and lacks hair"[37], had come from Commodore, Jay Miner, an engineer who had built the TIA (display chip) for the Atari 2600, had since left Atari to co-found Hi-Toro, which later became Amiga.

Atari had remained interested and had invested $500,000 dollars in return for access to the new chips that Hi-Toro was developing for its "Lorraine" machine, but when Hi-Toro/Amiga wanted more capital, it was Commodore which ended up buying the company and cancelling that contract with Atari[38], by now owned by Tramiel.

This led to a $100 million lawsuit against Commodore[39], which Chuck Peddle was quoted to have called "a great harassment lawsuit"[40] and which was filed partly as a response to a lawsuit Commodore had filed against Tramiel, alleging that several Commodore engineers that Tramiel had taken with him had "stolen secret material relating to Commodore's Z8000 chip project"[41].

The Amiga, formerly known as "Lorraine" was also a Motorola 68000-based machine, and the two computers were to become arch rivals. It was all incestuous stuff.

The 520ST was expected to be sold, with mouse, disc drive, printer and monitor for £1,000 (about £4,160 in 2026 money), which made it significantly cheaper than arch-rival Commodore's Amiga, even though the latter machine was generally considered technically superior.

Popular Computing Weekly commented:

"It is quite likely that Atari has better judged the market in the UK. Its 260ST offers a lot less but costs under half the price. The Amiga may be the machine you would love to own, but the ST may be the one you can afford"[42].

The threat of both machines was however enough for Apple to slash the price of its Apple IIc from £1,600 to £995, which included a 3.5" floppy, colour monitor, external floppy, mouse and software including AppleWorks.

It also reduced the price of the 512K Macintosh by £600 down to £1,795 (£7,460 in 2026).

At the same time Apple announced that co-founder Steve Jobs had left the company, and its income, although half the previous year, was better than expected at $12-$15 million[43].

Pricing for the 520ST was finally confirmed at the end of May 1985, at £899 for the basic model with a 1MB floppy and a monochrome monitor, as well as two other versions including a £700 version with no monitor but an RF modulator so it could be plugged in to a regular television and a third version with a lower-resolution colour monitor, although that wasn't expected until 1986.

Also confirmed was the rumour that neither the 130ST nor the 260ST would actually be released, a move which caused some disappointment as the more affordable £500 130ST seemed much better placed to bridge the gap between the home and business markets in the UK[44].

The 260ST did make an appearance in Germany, but the reason for its cancellation elsewhere was said to have been that by the time it came out, the cost of memory had fallen significantly, or as Atari UK's general manager Max Bambridge put it:

"We always said we would do a low-level machine and at the time we anticipated a 256K memory, but prices have degraded so much that we can now do 512K at the same price"[45].

At the time of the announcement, it was thought that there were still only around 40 520ST models in the UK, but that actual supplies should start reaching the shops in September[46].

Disk-drives come of age

Tramiel was also expecting 1985 to be the year when disk drives finally came of age and were cheap enough to replace cassette as the storage-medium-of-choice for home users.

At the 1985 Hanover Fair in Germany, Atari had already showed a 10MB disk, built in to their existing 1050 floppy disk drive unit, which was expected to retail for around £500[47] (£2,080 in 2026), trouncing the opposition.

Only a few months later, it was expecting to sell a 15MB hard drive which, as Tramiel pointed out, "could store the whole records of law for the last 200 years", for around £400 (£1,660) - a drop of £100 for 50% more storage.

This was a view backed up by Atari's software head Sig "Siggy" Hartmann - formerly president of Commodore Software[48] - who said in April 1985's Your Computer that:

"[cassettes] are gonna be a thing of the past. The whole market is shifting in to disk drives. Prices have to come down. Why should the consumer pay £200 for [floppy drives]?"[49].

The floppy format that came to dominate after it took over from the older 8" and 5.25" floppies - the 3.5" format launched by Sony - was initially rejected by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) as a standard in a vote that went 26 to 21 against.

Despite manufacturers trying other sizes like the briefly-popular 3" standard used by Amstrad, amongst others, Sony had already clubbed together with Shugart (the company that became Seagate and which was the inventor of the original 5.25" "microfloppy") and other manufacturers, and their standard eventually won out[50].

In the early spring of 1985, a brief rumour floated around that Jack Tramiel was going to personally head up Atari UK and leave the running of Atari US to one of his sons.

This caused some excitement in the Personal Computer News offices, which contacted Atari HQ in the UK to ask about the revelation.

Incumbent managing director Simon Westbrook said "it's news to me" and after a pause offered "it'll be news to Massimo Rosi [Atari's European marketing manager] as well"[51].

The video-games market wakes up

By 1986's Summer CES in Chicago, Atari was predicting the return of the video games market, the collapse of which it had largely caused and which nearly destroyed it, as it predicted it would sell two million consoles during 1986, despite competition from Sega and the new kid on the block Nintendo.

It was also suggested that this "unglamorous volume business" was "a good deal more lucrative than the ST", given plausibility to suggestions that Commodore's Amiga was matching or even outselling the ST in the US.

The slow take-up of the new 16-bit machines was also said to have highlighted the folly of the US software industry's early switch away from the established 8-bit market, which British companies were making the most of by filling in the gap.

However there was some concern that it wouldn't be long before traffic started to move back in to, rather than out of the UK, as Nintendo was planning to launch in the UK in 1987 with its Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and library of 37 games being imported by Mattel[52], and if its wildly successful test-marketing in Los Angeles and New York was repeated in the UK, it would sweep away everything before it.

Suddenly finding itself forced to write for Nintendo's consoles raised new issues for the UK industry as it now had to target cartridges and credit-card software, where - as Geoff Heath of Melbourne House pointed out - lead times were much longer and stock was harder to manage, but also that it closed off a huge source of amateur and freelance talent, as games consoles were essentially non-programmable.

However Herbie Wright of Firebird was more laid back about the risk, suggesting that Nintendo's arrogance in considering Europe as merely the 51st State of the US would keep it at bay, despite warning that success might yet come through a combination of "Japanese technology and American bullshit, which together is unbeatable"[53].

Atari and Commodore were still at it the following year, where the two companies both had "villages" at the 10th Personal Computer World Show.

Atari's had 30 seperate stands, which included a satellite weather station and a recording studio, whilst Commodore had taken an entire suite at the exhibition hotel to promote its new Amigas, but at least this year it was open to the public and not just invite-only trade.

Meanwhile, Amstrad had the next-biggest stand which was ironically right next to Cambridge Computer, whose boss Sir Clive was also the founder of Sinclair Research, which had been sold to Amstrad the previous year[54].

At around the same time, in something of a modern-day follow-up to the usage of a BBC Micro to cover the 1984 Israeli elections on television[55], the Atari ST was chosen by several newspapers and radio stations in the UK to provide election statistics for the 1987 General election.

It's fair to say that the forecasts of "The Election Program", as it was imaginitively called, were about par for the course for poll predictions, when managing director of software distributor Software Express reported "The latest projection gives a hung parliament with the Tories as the largest single party", with one forecast even predicting that the Ulster Unionist Party could hold the balance of power[56].

The actual result was a reduced-but-significant win for Thatcher's Tories, with 397 seats to Kinnock's 229[57].

Date created: 30 January 2014

Last updated: 30 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.