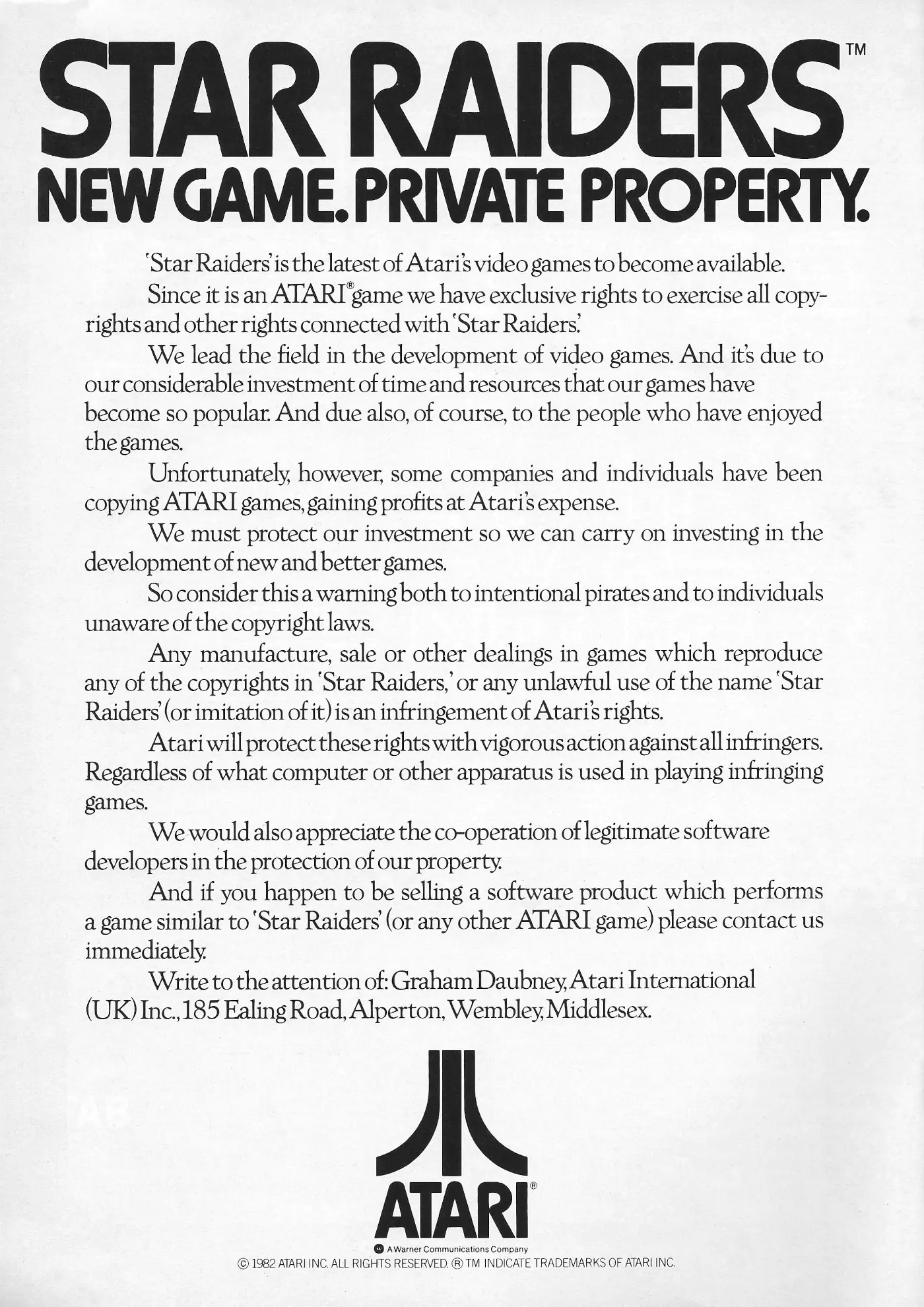

Atari Advert - December 1982

From Personal Computer World

Atari Star Raiders: New game, private property

This "advert", which appeared in the pre-Christmas edition of Personal Computer World and which encourages infringers to write to Graham Daubney - who would later become director of developments for Spectrum distributor Prism - is a legal nasty-gram from Atari showing that at least some things in the software industry have never really changed.

Although Atari had been fairly immune from pirating of its titles during the VCS/2600 era, when games were all cartridge-based, it was suffering a bit by 1983 thanks to things like the Mycard ROM copier manufactured in Taiwan[1].

However it was the advent of its 400 and 800 machines - which used cassette tape as a program/storage medium - coupled with the fact that its software was often considered overpriced which meant that it was now having its games regularly copied. And like Bill Gates before it, it was not happy about it.

Gates had written his famous open letter[2] in 1976 to the Homebrew Computer Club complaining about how Micro-Soft's Altair BASIC was being freely copied.

On one occasion, the "MITS Mobile", a converted camper van which was used to tour the U.S. and demonstrate MITS' products, like the famous Altair 8800, had visited the Homebrew Computer Club.

The paper tape that was used to store a pre-release version of Altair BASIC disappeared for a while, and at the following week's meeting 50 copies of it appeared in a cardboard box[3].

Atari was also vigorous in asserting its interests against fellow computer companies, stating that it would "continue to enforce its rights against those who would seek to misappropriate the fruits of Atari's labours"[4], by which it didn't just mean straight-up piracy but also the copying of "look and feel" or gameplay.

Pac Man eats the world

In particular, it took action against Commodore over its VIC-20 cartridge titles, which included Space Invaders, Pac Man and Midnight Drive.

Unfortunately for Atari, it turned out that only the name of Space Invaders was copyrighted, so all Commodore had to do was change the name of its version to "VIC Avengers", whilst keeping the actual game unchanged.

Pac Man, which was not even a game that Atari wrote but had bought from a Japanese company, ended up being sold in the UK by Commodore as Jelly Monsters, whilst Atari was also taking action against Philips over the same game[5]. Many of Commodore's other titles had to be changed too[6].

Atari had already dropped an interim injunction attempt against Commodore - to prevent it selling Pac Man/Jelly Monsters - in November 1982, after it had failed to secure injunctions against Hong Kong companies Video Technology and Soundic Electronics in the month before, for the same infringement.

The judge, whilst recognising that "the copyright of a computer program is not a clearly-defined area", had thrown the suit out because Atari had based its case on a "novel point of law".

The action to abandon the injunction was thought to be defensive - partly because of its failure in Hong Kong but also because of the risk that any failure to get an injunction against any particular Pac-Man clone would open the floodgates to all the other myriad look-alikes waiting for a chance to re-start their sales. At least bailing out on the legal action removed this particular risk.

Meanwhile, Commodore seemed to have been taken slightly by surprise by the move, with John Baxter commenting "Up until Tuesday we thought [Atari] was going ahead with the proceedings. We were ready to fight it", whilst an Atari spokesperson insisted that "Atari has not climbed down"[7].

Pricey software is blamed for piracy

One of the main drivers of the pirate or clone market was undoubtedly price, with continuous complaints that software prices were too high.

Atari really wasn't helping itself in this area when its new Atarisoft division, set up to develop software for non-Atari machines, started shipping its own version of some of these games - including Pac-Man - on ROM catridge towards the end of 1983.

An advert from Atarisoft, which features a dig at clones of the company's games, like Commodore's version of Pac-Man, which it called Jelly Monsters after legal pressure from Atari. From Personal Computer World, March 1984

Atari's prices were seriously un-competitive, with its cartridges going for £29.95 (around £130 in 2026) and tapes for £14.99 (£61).

This was at a time when Commodore's own cartridges were retailing for around £10, and Spectrum cassette games were available for around £6.

Atari UK's marketing manager Eric Salamon attempted to justify the price gouging by suggesting that "These are the best-selling games worldwide and at the end of the day you are paying for artistic input"[8].

Quite where the extra artistic input went on Pac Man to justify its £20 mark-up was not specified.

The issue of software prices never really went away, as even by 1986 a report by market-research company MORI was showing that 25% of children were using tape copying as their most favoured way of getting software - primarily games - partly because of the convenience, but largely on account of the cost.

The same report highlighted how only one in ten parents believed that they knew more about computers than their kids, with the natural conclusion being that the activities of these feral "computer kids" could "spawn a generation of software pirates"[9].

Guy Kewney of Personal Computer World also questioned the approach being taken, whilst disagreeing that piracy was quite the problem that software houses claimed it was.

In a lengthy piece entitled "Integrity", published in July 1983's issue of Personal Computer World, he referred to a case where a software producer had recently accused some children of "stealing" software because five of them had clubbed together to buy a program, presumably to share it as they otherwise wouldn't have been able to afford it.

Kewney came up with an analogy: "if everybody could get books from libraries without paying, what would happen to the book shops? And without bookshops, what would happen to books?"[10].

Tape-to-Tape software copying

Back in 1982, a software publisher - Julian Allason - had also complained about tape copying, saying that "it has destroyed the computer games software business".

His company was PETSoft, the Edgebaston-based subsidiary of ACT, which by June 1981 was producing only 20 software titles, down from a high point of 200.

Allason attributed this situation to the habitual sharing of software among friends, although he conceded that the shift to floppy disk may have contributed to the slump.

Allason also didn't believe that price was a factor, suggesting that it "did not seem to matter whether the program cost £3 or £150"[11].

Meanwhile, Personal Computer World's Kewney pointed out that all of PETSoft's programs were out of date anyway and that other software authors, in particular those of "totally copyable Spectrum games", were earning £35,000 a year (about £154,600 in 2026) at the age of 17 and were getting invited to dinner with Margaret Thatcher.

By 1983, the industry worried not just by increasing home taping but by the increase in "software libraries" and exchange clubs. Commodore's marketing manager John Baxter said of the issue that:

"Stopping individual libraries is very difficult. Industries much larger than our own - the record and video business for example - are trying hard to fight a similar sort of problem and are failing, so there is no easy solution".

Commodore was in an unusual position in that it was one of the few micro companies that only supported its own dedicate tape records, or "datasettes".

This gave it the ability - which it used throughout the tape era - of "changing the design of [its] cassette player to make it incompatible with a normal audio player", which went some way to reduce the scope for tape copying, or at least make it more of a chore.

Commodore, along with other companies, also had the option of moving software off cassette to ROM or floppy-disc, however these devices were more expensive and could alienate possibly millions of owners.

But it wasn't just unofficial software libraries that software houses were worried about, as even regular book libraries were getting in on the act, with Thanet public library offering a small scale software loan facility by the spring of 1983[12].

Just a week later, at the Spider's Web Motel in Watford, 28 members of the Computer Trade Association - micro builders, retailers and software companies - met to discuss the problem of software libraries, with Nick Alexander of Virgin games suggesting that even if home taping could be curtailed, software libraries would still be a "bad thing".

Computer magazine Popular Computing Weekly seemed to agree and had taken something of a stand by refusing to accept adverts from software libraries that "hired out tapes without the publisher's permission"[13].

Alexander continued "Because rental took off in the video market, dealers got involved in such cut-throat competition that they didn't have enough revenue to plough back to buy new releases - the same thing could happen with games".

Meanwhile Salamander's Nick Lambert was frustrated that the only apparent control the software companies had over their own software - that of first-party sale, i.e. how, when and to whom software could be re-sold, could not legally be written in to the terms of sale.

The CTA wrapped up its meeting with the somewhat obvious statement that "The CTA is opposed to any form of hiring or lending of tapes, discs or cassetts by direct or indirect means without the authority of the author of the program"[14].

The CTA had been set up only a few weeks before, and had formed out of the Society of Computer Manufacturers, Agents and Dealers, itself a micro-industry group which had been set up only a couple of months earlier in February 1983.

This earlier group counted Atari, Bug-Byte, Camputers and Tandy amongst its membership[15].

The CTA immediately set up a committee to investigate "questions of copyright and software lending", with a watchdog to monitor lending libraries and the option of trying to scare up a test case at law[16].

There was also concern about piracy within the ranks, or at least with some of the less-tied retailers within the group. In April 1983, software house Quicksilva and the retailer Software Centre resolved a dispute over the latter's buy-back scheme, in which customers had six months to try out software and return it, in return for an 80% discount on future purchases.

Under the terms of the agreement, Software Centre was forced to reduce its Buy 'n Try buy-back deadline to only one month, even though this wouldn't really have much of an impact.

Other software producers were looking closely at the case, with Sinclair suggesting that "The practical way of stopping [Software Centre's] actions is to stop them getting any product - and that is what we are now turning our attention to"[17].

The tax-man cometh

An early advert for Imagine, © Personal Computer News 1983Meanwhile, the sometime-excesses and overt successes of the microcomputer and software industry - epitomised by the crash of software house Imagine in 1984, with its fast cars and expensive office furniture - were starting to attract the attention of the Inland Revenue, which by the summer of 1983 had set up a special investigatory team.

The Revenue was particularly concerned that a "large number of new companies that [had] sprung up in the last couple of years [were] failing to fulfil their tax obligations", by which it generally meant that falling hardware and software prices would bankrupt these companies and the Revenue would not get any taxes.

Somewhat sinisterly, the IR was collecting evidence from adverts as well as from interviews with key participants in the industry, or as Tony Slater of the Revenue's Bristol Special Office said "I am interested in finding out as much as I can about the home computer business - hardware and software - from the top to the bottom".

Computer software was especially tricky and prone to loopholes as it was covered by at-the-time fuzzy laws governing "intellectual property". One loophole meant that even best-selling software was considered "worthless at the point of its creation", which left room for creative accountants to maximise profits with the minimum of tax liabilities[18].

The anti-piracy Arms Race

There were some early legal moves to combat piracy during the late summer 1983, as both the UK and EEC (EU) parliaments were looking to change copyright law to cover computer software, however things were going slowly.

In September the British Computer Society tried to set in motion a Private Members Bill to amend Copyright law, which at the time was a patchwork of amendments to the original Copyright Act of 1956. Bob Hart of the BCS said:

"we would like to amend the current Act to ensure that copyright would extend to software programs, making them alternative expressions of a literary work".

The stimulus behind this was a meeting of WIPO and UNESCO in June 1982, which concluded that "the problem should be couched in existing copyright law", although this was thought by some technocrats in the EU to be strange as it didn't address the problem, as posited by Personal Computer News, of translating software from, say, Fortran to Cobol - the equivalent of producing a pirate Spanish edition of an English book[19].

Throughout 1983, the arms race between software houses, pirates and mainstream companies offering ways around protection was hotting up. On releasing its "Copy II" program, Tony Riley, managing director of Orchard Software said:

"When I read yet another article about rampant piracy, I just have to yawn - our customers are mainly big business types who will happily pay for their software and who just won't risk using pirated copies - but they do need backup".

Version 4 of Orchard's program came with all the latest methods of circumventing copy-protection, including those based upon "self-synch bytes" and "synchronised tracks". Riley continued:

"we expect to be offering a bit-copier for the IBM PC soon, now that it is being marketed here in the UK. That will probably cause yet another round of indignation from people who refuse to face facts. Serious users need reliable backup"[20].

By the autumn of 1983, software publishers were getting more technical with counter-measures designed to prevent copying.

Recent Acornsoft programs had been modified to prevent copying to disk, and software from Imagine went as far as to use the system clock to stop copying.

Even Sinclair's new Microdrives also featured copy protection designed to stop easy saving from tape to "disk".

Guy Kewney was still raging about the whole situation, pointing out how users always found a way around such things and citing the "nibble copy" programs popular in the US. He continued:

"For every time that the software company wastes its time working out a new protection method, we can count one more game that the programmer could have written in the same time, which would have actually generated money".

Proposing that there should clearly be a law to prevent copying for sale, he concluded that this might make the industry less paranoid and "less prone to mindless vandalism of the sort which prevents me from running my programs on my diskettes[21]".

This came to a head towards the end of 1983 when the magazine Personal Computer World published details explaining how to break Acornsoft's copy protection so that users could save their cassette software onto disk.

Acornsoft was "furious" and took the publishers to court. It was asking for the removal of that month's edition from bookshops and newsagents, and was also seeking an injunction claiming that the article was "inviting others to infringe Acornsoft's copyright".

Personal Computer World settled out of court for £65,000 (about £274,500 in 2026), with the editor Jane Bird saying:

"One feels a little bit sad about it, but the situation was that it could have been a long battle and we would have lost the issue".

BBC Micro-focused magazine The Micro User approached Acorn to ask if, now that the procedure was public knowledge, it could also publish the details. Acorn replied:

"Yes, if you want. We'll add the money we get from you to the coffers - we're using it to find a new way of locking programs"[22]

The arms-race continued throughout 1984. In the spring, games company A&F Software - makers of Chuckie Egg and Cylon Attack - announced that it was offering a £5,000 (£21,100 in 2026) reward to anyone who could "beat the software pirates". Director Martin Hickling told Acorn User that:

"some computer club members spend hours every week duplicating tapes for their friends, thereby risking hefty fines or jail sentences".

The company stated that it intended to prosecute every pirate caught, and that it was planning to manufacture "copy-proof" tapes.

Meanwhile, A&F had had several replies to its offer, including one from a "mystery sixth-former who insisted on a midnight meeting in a car park"[23].

By the autumn of 1984 it was being reported that a group had been set up in the Netherlands specifically to help pirates organise.

The 'International Cracking Agency' was also circulating a cracking disc to recognised software pirates which contained details of how to circumvent the protection of much commercial software of the day. CRL's Clement Chambers said:

"it's getting so bad that you can't release a new title slowly through Europe - two weeks after the program is launched in the UK, pirated copies are available in a number of other countries and you haven't got any market left. If we could find out who is behind this International Cracking Agency they'd be in the Thames with a set of concrete wellies"[24].

Nick Alexander of Virgin, © Popular Computing Weekly 29th September 1983Also in 1984, the Guild of Software Houses (GOSH), which had been set up the previous year as a pro-software-copyright collective between several major games companies including Quicksilva, Softek, Salamander and Virgin, had established a special anti-piracy committee.

This came at a time when software companies were being criticised for their general lethargy in tackling pirates, although some had started to get more pro-active, with Software Projects and Microdeal in particular "taking the gloves off".

Software Projects' Alan Maton promised "if we know of someone who is breaking the law we'll take every step to make sure our investment is protected. We're fighting fire with fire".

Maton took particular issue with the pirating of popular Sinclair Spectrum game "Jet Set Willy", with several work-arounds for the game's print-based colour-coded protection chart (providing the codes needed to start the game) appearing in the press[25], even though there was actually more protection for this sort of piracy as at the time the law was much clearer on the copyright of printed material.

By the end of May, GOSH had ramped up its war as it set up a legal fund to be used to fight software piracy.

Over £50,000 had been pledged from 21 members companies at a meeting in the week of the 24th May, with GOSH chairman Nick Alexander saying "All we have to do now is find a suitable case to fight - and believe me there are plenty of deserving causes"[26].

Software piracy eats itself

In July 1984, Microdeal was in the news again for all the wrong reasons.

In the middle of the month it had taken two brothers from Blackburn to court to halt a commercial piracy operation, but only a week later found itself being sued by US company Activision over Microdeal's Cuthbert in the Jungle, which Activision was claiming was a copy of its game Pitfall. Geoff Heath, the UK managing director of Activision explained:

"We applied to the court for an injunction to prevent Microdeal selling Cuthbert. However, after reviewing the writ and our prosecution papers, Microdeal obviously felt our case was watertight because they didn't fight it"[27].

It was becoming something of a pattern for Microdeal, as the company had been hassled the previous year by Nintendo over Microdeal's suspiciously-named game "Donkey King", which was apparently in no way a knock-off of Nintendo's Donkey Kong.

That action was prevented when Microdeal announced it was changing the name to "The King". As David Kelly of Popular Computing Weekly pointed out

"It just isn't good enough for software houses to start kicking up a stink about piracy - forming themselves into groups GOSH and FAST, with the aim of fighting piracy - when their own house is in such disorder"[28].

The challenge from commercial-scale piracy ramped up towards the end of 1984 when it was discovered that Portuguese company Microbaite Software was copying Spectrum software.

However, this wasn't just the odd tape, but was the systematic copying of games from a variety of software houses which included full-colour printed cassette inserts and everything. There were around 54 different tapes available, each of which contained two different top-selling titles.

Not one of the 100 or more titles on offer had actually been authorised, and Quicksilva, which had at least eight of its titles on the pirate's tapes, didn't seem impressed, with the company's managing director Rod Cousens commenting "Portugal seems to be one of the main offenders for this type of organised piracy. It's not the kids copying stuff that worries us so much as this kind of professional outfit".

As well as Melbourne House and Beau Jolly, Psion had also been targetted by Microbaite.

The company's product director Peter Norman reckoned that Psion "[would] pursue this extremely vigorously. We always go to great lengths to stamp out professional piracy"[29].

The actual chances of any of the affected companies being able to realistically do anything about it, given lack of international cooperation - even though Portugal was a signatory of the Berne Convention on copyright - were however remote.

By the summer of 1986, GOSH had been disolved on account of its dwindling membership. Its last chairman, Mike Meek of Mikro-Gen bailed out stating that "there was little point in continuing"[30].

However, legal action from its members continued as the case that Microdeal had taken out in Blackburn back in 1984 finally bore fruit, with a judgment against Dr T. Mohamad, who had been selling a compilation of Microdeal's games for £30, coming in at the very end of 1986 after a "long and lengthy trek through the courts", with a win for the plaintiff of £9,262.98[31], or about £34,100 in 2026.

There was also a win for Pride Utilities, an Amstrad software supplier, in April 1987 against its former French distributor ESAT. ESAT had previously been a significant customer of Pride, but the latter company noticed that orders had been slowly dropping off towards the end of 1986.

After Pride sent in agents to investigate, it turned out that ESAT had been duplicating Pride's software "on a large scale".

As well as a settlement against ESAT for an outstanding bill of £9,000, the company also kicked off legal proceedings in the courts of Bordeaux over ESAT's rampant piracy, just before Christmas 1986, action which was still ongoing by the spring of 1987[32].

Copyright legislation finally appears

The root of the problem - in the UK at least - lay in the way the Copyright Act of 1956 had been framed.

The act was set up to protect written "literary works", which could also include "any written table or compilation", but where writing was defined as "any form of notation, whether by hand or by printing, typewriting or any similar process".

As Practical Computing pointed out in an article called "The copyright controversy" in August 1980's issue, this could be taken to mean that a program in ROM or on a magnetic medium is not "writing" because it was invisible to the eye[33].

It went on to point out that once a literary work had been copyrighted, it was protected from unauthorised publication in "any material form", which might mean that copyright could be obtained by listing the program out on paper.

This has shades of a court case in the US between Franklin - a builder of an Apple II clone - and Apple itself, where Franklin had defended its copying of Apple's software by stating that as software wasn't generally printed out it couldn't be copyrighted.

The Philadelphia Federal Appeals Court eventually disagreed and wrote that "The medium is not the message", a precedent which paved the way for the copyright protection of all software in whatever form in the US[34].

That was in 1983, but in the UK it was not until 1985 that actual legislation started to appear.

Before that, there had been sporadic legal action based upon existing law, including the £400 fining of a London council worker - who had taken several months to track down - under the Trade Description Act for selling fake copies of games at half the normal retail price, and a bigger case at the High Court involving Thorn EMI and MirrorSoft as plaintiffs.

The four defendents in this case got off lightly, with a promise not to do it again.

There were also some successes, with two men from Salford being charged in the spring of 1984 with possession of 13,000 professionally-copied tapes, complete with full-colour cassette inserts, including fake titles from major software houses Psion, Quicksilva, Ocean, Ultimate, Imagine and Durrell.

The pair were charged with criminal deception as well as offences under the 1956 Copyright act and were bailed, pending appearances in court, for £10,000[35].

By around April 1985, actual targetted legislation, in the form of the Copyright (Computer Software) Amendment Bill, had received an un-opposed third reading in the House of Commons[36].

It became law on the 16th of July. Penalties included unlimited fines or up to two years' imprisonment for manufacture, distribution or importing of "pirate" material, whilst selling or possession could incur fines of up to £2,000 - about £8,040 in 2026.

An enforcement unit to back the new law up had also been set up, which was headed by former Chief Superintendent Bob Hay. He was perhaps best-known for his work at the command centre during the Iranian Embassy hostage siege[37].

One unexpected result of the passing of the act came at the end of 1985 when MicroPro, retailers of the best-selling word-processor package at the time, WordStar, announced an amnesty for people using pirate copies.

At the time, there were thought to be around 1.5 million licenced copies of WordStar in use, with about 85,000 of those in the UK.

However, MicroProse believed that there were about four times that number - 340,000 - pirate copies in use, including in large corporations where it was thought that many people would have simply "backed up" their colleague's genuine copy.

The amended copyright act gave software companies a lot more "clout" in the anti-piracy fight, but it seemed that MicroPro was taking a pragmatic approach by giving users the chance to send in their illegal discs along with £40 in order to upgrade them for a legitimate version.

Instead of the cost of legal action, the move was considered to at least give MicroPro a chance to recoup some of its lost revenue, whilst still being sufficiently expensive to deter large-scale counterfeiters from trying to legitimise their own dodgy copies[38].

Meanwhile, the "William Powell Computer Copyright Bill" as it was also known, could also be used against several companies at the time which were producing hardware devices that could dump the contents of memory on to tape or disk, ostensibly for the purposes of "backing up".

One such company was Evesham Micros, which was selling the "Interface III", a small plug-in module which could dump a copy of any running program to tape at the touch of a button.

The worry was that "a new wave of piracy could be the last straw for the ailing software industry"[39].

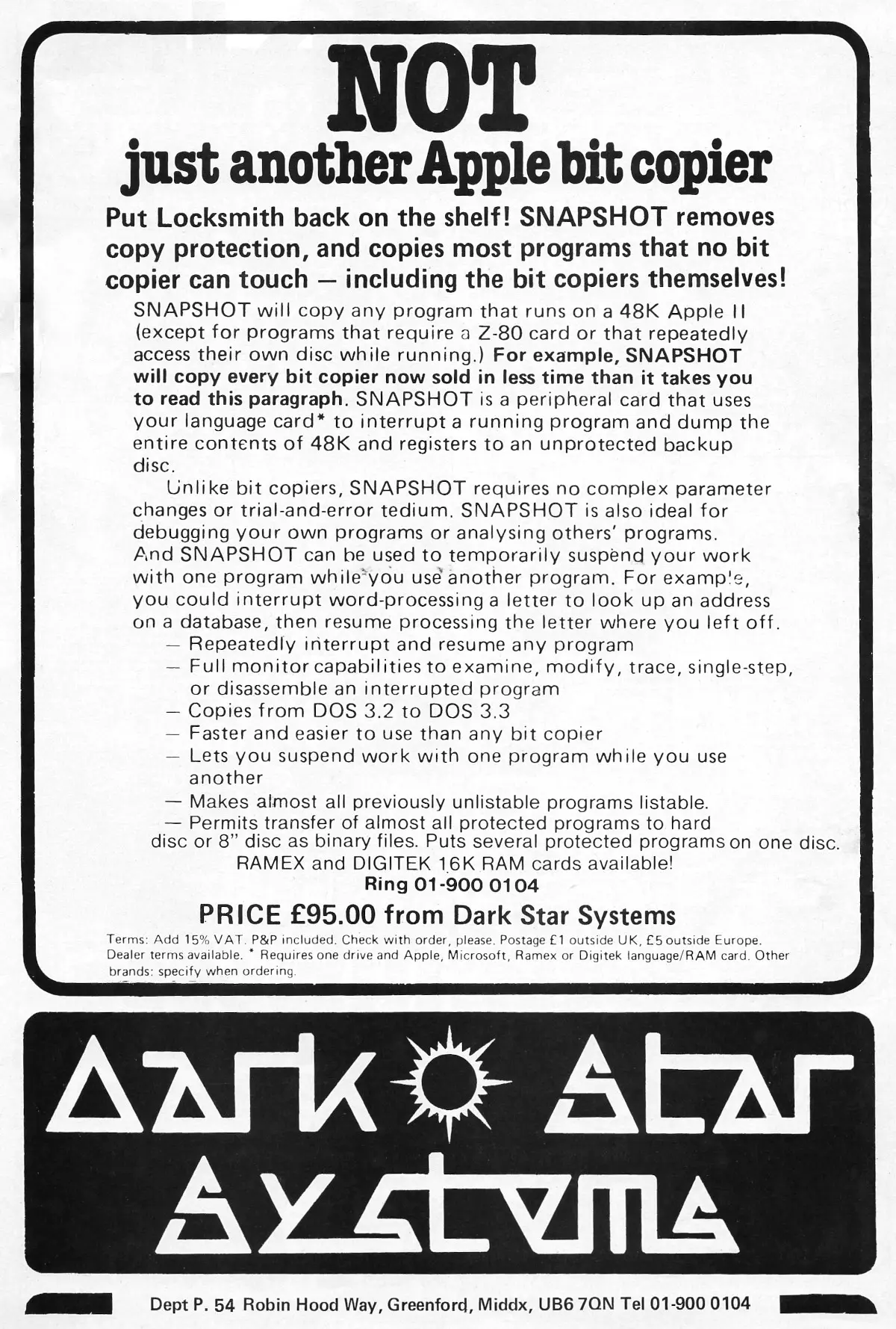

Such devices had been around in various forms for a few years, such as 1983's Dark Star "Snapshot", a plug-in card for the Apple II which was capable of dumping a running program to disk.

Called "not just another bit copier", it could "remove copy protection and copies most programs that no bit copier can touch - including the bit copiers themselves".

An advert for Dark Star's bit copier - possibly the pinnacle of copiers as it was able to operate at the hardware layer. The 6502 processor in the Apple II that this was aimed add did not implement things like protected memory, so anything that could read memory at the hardware layer had access to everything. From Personal Computer World, December 1982

The device, which retailed for £110, or about £480 in 2026, was also billed as a primitive multi-tasker, as it was possible to use it to effectively halt a running program, let the user run something else and then return to where they left off[40].

A couple of months later it was Commodore's turn to consider taking legal action against another bit-copier - the General Hardware Company - which was offering a device that could copy VIC-20 ROM cartridge software.

A Commodore spokesman said "We are very concerned and the matter has now been referred to our solicitors who are considering the next move"[41].

Amstrad suffered its fair share of embarrassment as it was taken to court in 1985 by the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) for its double-decker tape deck with high-speed copying.

Mr. Justice Whitford of the High Court stated that this was "an inducement to infringe copyright", with Amstrad's unique problem being that it was both a manufacturer of the double tape deck - which featured in its range of budget Hi-Fi - as well as a commercial software house trading as Amsoft.

The case cost Amstrad £100,000 (£402,300), plus further damages to be determined, although the company vowed to appeal against the ruling[42].

In his defence, Alan Sugar actually produced a bird watcher who used the Amstrad double tape deck to make copies of bird song for friends, as an example of "the typical tape-to-tape cassette user". The judge was "not impressed"[43].

It was all perhaps a little unfair as there were other tape duplicators around, albeit clearly aimed at business. For instance, Sound Electronics' CD 201 high-speed cassette duplicator was launched in May 1984 and could be had for a snip at £1,290 or about £5,440 in 2026.

Public domain software and shareware

The appearance of legislation more-or-less coincided with something of a shift in the software industry, as alternative business models were starting to appear in which copyright was willingly waived, in part or in full.

The first of these models was Public Domain software - programs that were offered for free with no strings attached by their authors, for the benefit of anyone and everyone.

Public Domain - like many things in computing - had been popular in the US for years, but that probably reflected the entirely different price structure for telecommunications as much as anything.

In the UK, even local calls were charged, whereas in the US they were largely free, which meant that over the pond it made perfect sense to dial up a bulletin board system and download some software.

That was not a cheap thing to do in the UK, as even off-peak calls were still relatively expensive.

So as an alternative, UK businesses like Workman and Associates were offering compilation disks with hand-picked public domain software programs on them.

For £32.50 per disk, users not only got sort-of instant software (allowing for postage) but perhaps more importantly they were getting programs that had been vetted and verified.

Slightly cheaper, at only $15 per disk - which included the media itself as well as the postage - was a collection of some 6,000 public domain programs from the US-based Folklife Terminal Club, available for many of Commodore's computers, including PETs, the VIC-20, C64 and the Plus/4[44].

It wasn't risk-free however, as whilst public domain software might have been free, it could also be a dangerous place as programs wouldn't always do what they advertised. Such software would frequently become the target of virus writers.

The idea of such compilation disks wasn't a million miles away from the approach of Adam Osborne - of the Osborne portable - who famously used to ship what the company reckoned was £800-worth of software with its luggable Osborne 1, for "nothing".

This approach was far removed from the usual concept of traditional "premium" software, the price of which seemed to be based more on the perceived value, or what companies thought users might pay - and maybe which machines they were running it on - rather than how much it actually cost to write or produce.

Osborne - referred to by Computing Age in its January 1986 edition as a free-market iconoclast of the computer business - was intending to plug the same gap in the market for the IBM PC, with a range of quality-but-cheap software under the Paperback Software brand.

Valued on what Osborne called a "cost related" basis, he was claiming to have actually worked out how much a package, for instance the word processor Paperback Writer, actually cost to write, and would sell it at that cost, with a modest mark-up to generate just a bit of profit.

The next step up, after public domain, was shareware. This was software that was still freely available and downloadable, but which was maybe missing something like documentation, support or software updates.

The idea was that potential customers could either copy their friends' software - with implied permission - or pay a small amount for a disk, but if they liked the program they could pay the "full price" - maybe £50 or something - and get all the extras.

If they didn't, then that was fine too, or as Computing Age suggested "no black Cadillacs containing teams of lawyers will draw up outside your house".

As Computing Age also pointed out, the way shareware worked was almost the same as the WordStar amnesty, except from completely the opposite direction: pirate the software and pay the amnesty versus copy the shareware and pay the upgrade. Same outcome, different point of view, except for the lawyer thing[45].

---

Following the dissolution of GOSH, the mantle of fighting piracy was taken up by a new trade association, the British Micro Federation, which had been set up in October 1986 and which held its first AGM on March 25th 1987.

With a wider remit, including anti-piracy and establishing codes of practice for members' own protection as well as that of the consumer, alongside a role as a lobby group to Government, the committee of the BMF comprised, amongst others, of Paul Welch of Atari UK, Geoff Heath of Mastertronic, Clive Booth of ComputerLand, the editor of Popular Computing Weekly - Christina Erskine - and Microsoft's David Fraser as chairman and the representative for "business software"[46].

Fraser would become vociferous in the ongoing war over the BBC's patronage of Acorn[47].

Date created: 19 November 2019

Last updated: 30 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.