Amstrad Advert - April 1990

From Personal Computer World

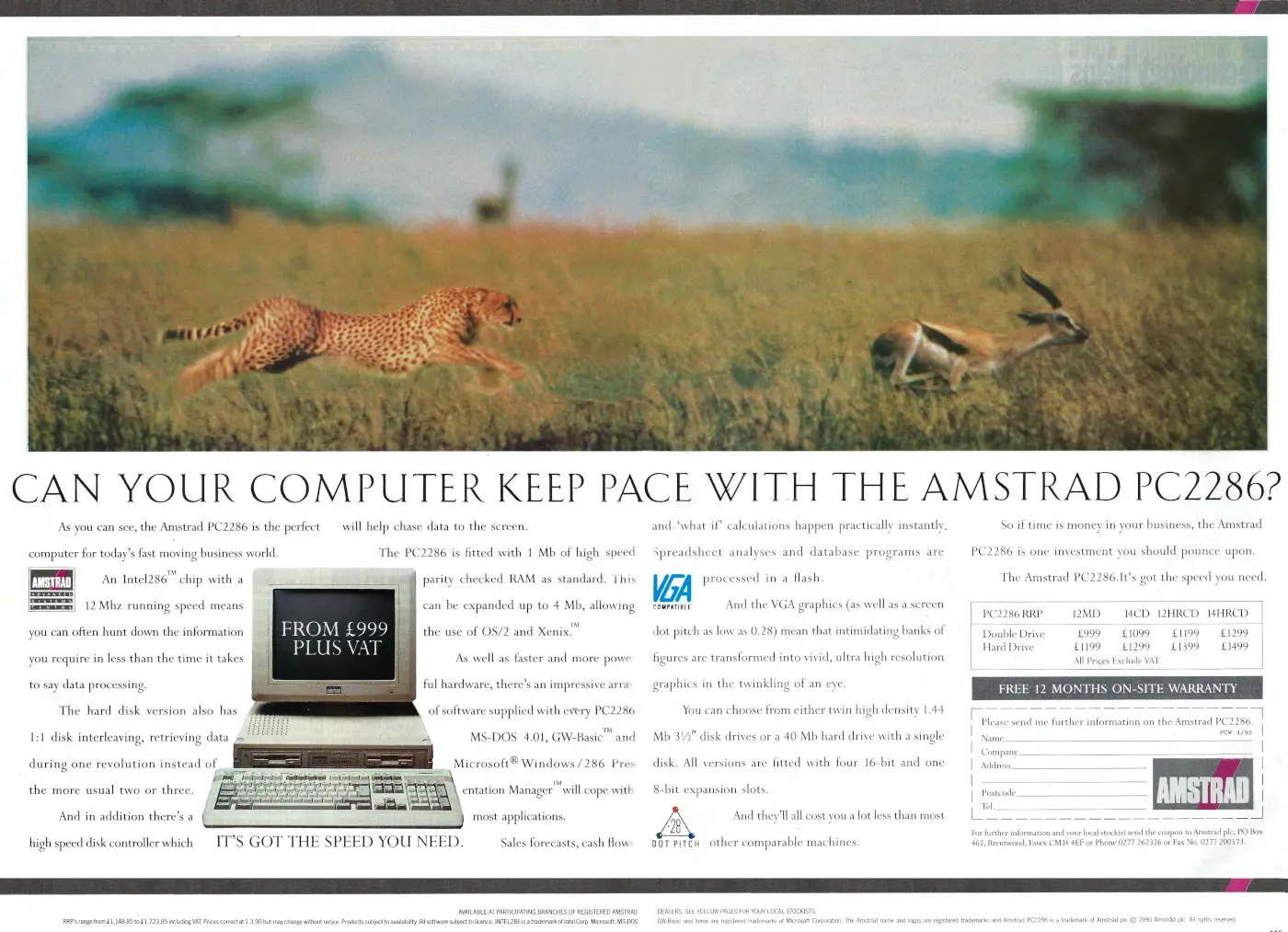

Can your computer keep pace with the Amstrad PC2286?

Several years after Amstrad had battered through the UK home and small-business microcomputer industry with its range of keenly-priced machines, it was still going, here offering an Intel 80286-based machine with double floppies or a single floppy plus hard drive.

In the intervening years, standard memory had gone from 128K to between one and four megabytes, video was up to the VGA standard (640x480 pixels) and hard disks were providing more like 40MB of storage.

Amstrad's top-of-the-range PC2286 was retailing for £1,700 - about £5,470 in 2026.

The previous year had been what Amstrad called "disastrous", as it marked the first time that the company had not posted a profits increase - making as it did a modest £75.3 million on sales of £348.7 million in the first half of 1989.

Alan Sugar said that this was "disappointing", attributing the fiscal failure to "a chain of events some outside our control and others the result of our own mistakes".

The company also announced that for the first time some of its manufacturing would be done in the UK.

A deal with GPT (GEC-Plessey Telecommunications) would see Amstrad's PC2286 and PC2386 base units and keyboards being manufactured at GPT's plant in Kircaldy, Scotland, where it was hoped that up to 10,000 machines a month would be produced.

That would mean around 20% of Amstrad's total output would be produced in the UK as long as, in the words of Alan Sugar, Amstrad's margins weren't affected[1].

Some sources were suggesting that each computer built in Kircaldy was actually costing Amstrad £10 more than one manufactured in Korea.

However, that seemed a reasonable cost to potentially side-step investigations by the European Commission into the dumping of goods made in the Far East into the European bloc. It was thought that this had triggered Amstrad's partial move back to the UK[2].

The commission's previous focus had been on printers, with tariffs up 40% or more being imposed, but the rumour from Amstrad's government contacts was that computers would be next[3].

Although some of Amstrad's financial failings had been lain at the door of a worldwide DRAM shortage and manufacturing problems in Germany, it was also said that Amstrad as a company seemed to be losing its way.

There were reports of machines not working, not shipping at the time they were supposed to launch (although this was pretty much the de-facto situation for micro companies in the early 1980s) or where various parts of bundles were simply missing.

As Computer Shopper said - "no longer is [Amstrad] made to look professional by the calamaties of rivals".

The other problem was that Amstrad was pitching its keenly-priced (a.k.a. cheap) machines against the likes of IBM, Compaq and even Olivetti - in a business market where being cheap almost seemed to be counter-productive.

Also, Amstrad wasn't even intending to bring out any new models during 1989, when competition was fierce and Amstrad didn't have much in the crucial [Intel] 286/386 market[4].

The shortage of RAM that contributed to increasing microcomputer prices and saw shortages of machines in shops came to a head during 1988 when Amstrad was forced to buy a share in a chip company just to ensure supplies and to avoid crippling spot-market prices when supplies became scarce.

By 1989 there was hope that such shortages might become a thing of the past when the idea of trading in RAM futures started to gain favour.

The idea, which came over from chip-market traders in the US, was simply that consumers like Amstrad or Atari would buy their chips in advance from the newly-set-up Memory Clearing Corporation at a set price.

Delivery would then be at a pre-arranged point in the future, thus smoothing out supplies and removing any advantage to manufacturers from stock-piling their output[5].

Date created: 28 November 2014

Last updated: 11 December 2024

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.