Amstrad Advert - January 1987

From Personal Computer World

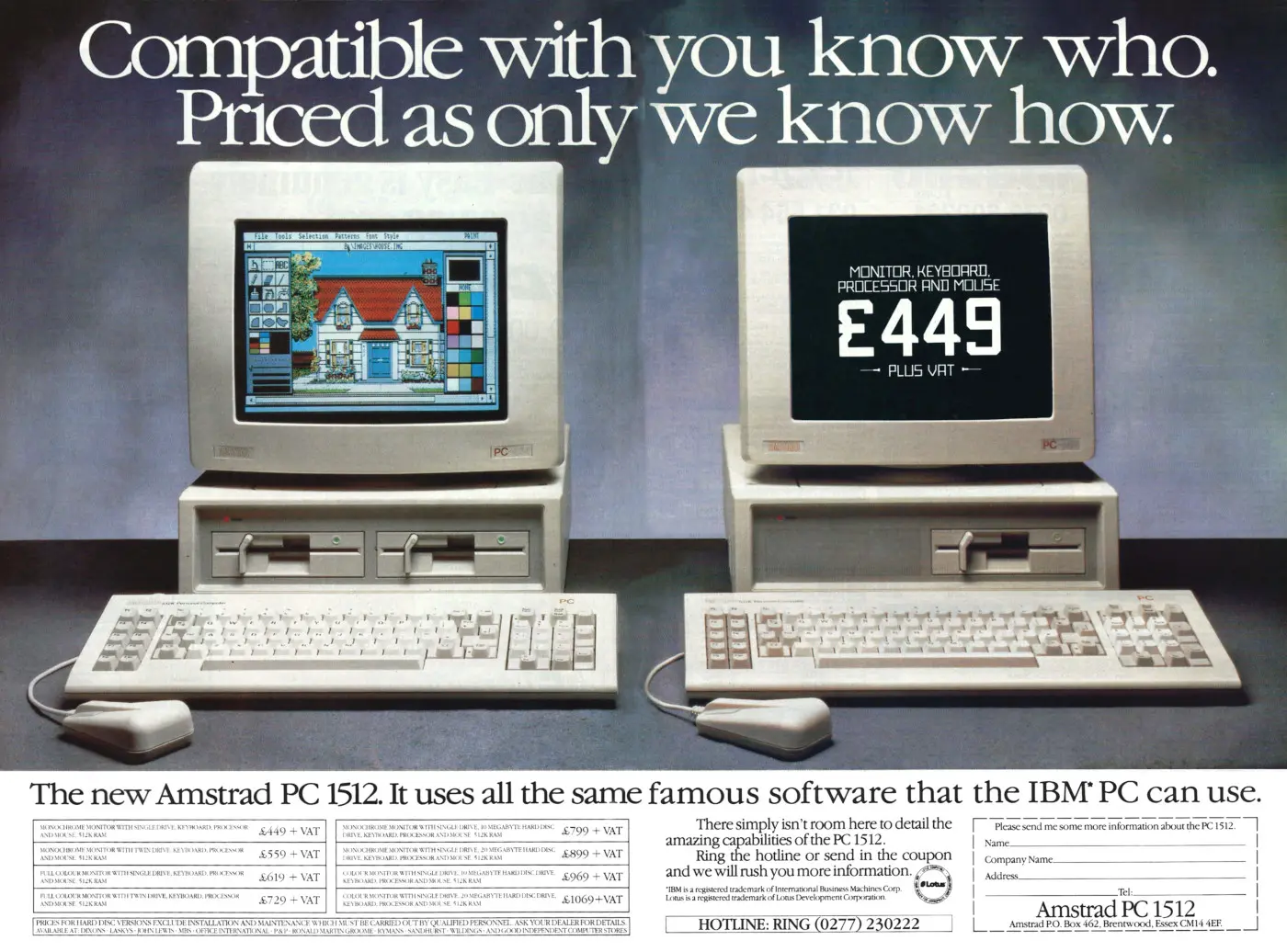

Compatible with you know who, priced as only we know how

At £449 (£1,640 in 2025) Amstrad wasn't wrong, although that was for the machine which only had a single floppy.

The more useful version with a 10MB hard disc drive retailed at only £920 including VAT (£3,370), which was still very cheap for the time and made the PC 1512 a popular machine, especially with home users.

As such is credited with being the first machine to really open up the PC market to consumers rather than business[1].

It all goes to show that even Amstrad was not immune to the IBM PC juggernaut.

Its previous CPC machines had featured the company's own Locomotive Basic and ran on an Z80A, whereas the PC 1512 was firmly in the IBM camp, running an Intel 8086 and MS-DOS 3.2 or Digital Research's DR-DOS.

Alan Sugar had previously put down some of the company's success to the fact that it didn't try to break in to Europe or the US.

However, after a year of consolidation in 1986 during which Sugar considered that Amstrad had "mopped up the vast majority of micro users he can get to in the UK", the company finally started on something of an expansion spree.

It added subsidiaries in Spain, Italy and the US, in the form of distributor Vidco, which Amstrad bought in the September of 1987 for $7.5 million.

The purchase of Spain's Indescomp set Amstrad back £21.6 million, or about four times the amount it had paid for Sinclair just a year before.

Things were a little trickier in Germany - the first international market that Amstrad entered. Its existing partner Schneider, which had been selling re-badged Amstrad machines, was keen to sell newer hardware, but Amstrad wanted control of distribution, so the two were set to part ways in the spring of 1988.

It was even thought that Schneider might even sell its machines in to the UK[2].

An Amstrad advert placed in a French magazine, showing the PC 1512 in a bundle offer with a printer for 1500F instead of 2290F, which is about a £79 discount, or £280 in 2025. The advert also claims that more than 800,000 1512s had been sold to businesses and home users.

In Italy, in a break from its previous form of subcontracting existing distributors to handle its machines in foreign markets, Amstrad actually set up its own subsidiary of Amstrad S.p.A, headed by Ettore Accenti and staffed entirely by Italians.

With a potential market thought to be around 600,000 units, Amstrad S.p.A was not only selling the parent company's micros, but also its consumer stuff, like Hi-Fi and video players[3].

Amstrad had been struggling selling into the US, not unlike pretty much every other UK retailer which had tried, and hadn't achieved much market penetration with its 1512s, PCWs and CPC machines.

To try and perk things up a bit it had moved over its distribution from mega-retailer Sears to Vidco earlier in 1987, a move which Alan Sugar suggested would "give Vidco the means to become highly competitive and at the same time capitalise on the market's potential".

He continued "We have learnt that the US market is very competitive and frankly there seems no room for a middle-man distributor"[4].

Jack Attack

Back in 1986, Amstrad had the UK micro market pretty much to itself with its newly-acquired Spectrum, on account of Commodore's financial chaos which saw it lose £25 million in the first quarter of the year.

It was doing well enough for founder Alan Sugar to sell 5,000,000 of his shares - the cash to be "for his own personal use" - for an estimated £26-28 million, valuing the company at around £500 million and with the offer being "considerably over-subscribed".

However, by 1987, Atari - now owned by ex-Commodore founder Jack Tramiel - was back as a serious competitive force.

Atari launched its XE games console - a version of the Atari 400 without a keyboard, although this was available as an extra - as a competitor to the Spectrum, but more significantly the Atari STFM had its price cut to only £299, which with its 16/32-bit 68000 compared to the 8-bit Spectrum Plus 3 at £249, looked the much better deal[5].

Amstrad wasn't sitting still though, and had just re-launched an update of its PCW - the 9512 - at an office equipment show in Atlanta.

To the bemusement of the US market, the PCW still used the niche 3" floppy disk format and also still ran CP/M, the operating system that was once dominant in the 1970s but which was by now very much fading away.

The previous launch of the PCW had failed in the US, but Amstrad was hoping that its new machine, with Locoscript 2 and a paper-white monitor for only $799 (£499 in the UK) would reverse its misfortune[6].

Locomotive Systems, from Dorking in Surrey, provided the LocoScript word processing package on the PCW8256 and later models. Here, it's offering the update LocoScript 2 - which was being supplied with the latest PCW9512. From Popular Computing Weekly, 7th August 1987

Meanwhile, The US launch of Amstrad's PC1512 "IBM Compatible" was somewhat overshadowed by a return to the offensive from Atari, which chose the same January 1987 Las Vegas CES show to launch its own PC compatible, together with three new STs and a radically-cheap laser printer, apparently stunning the crowds in the process.

Atari had been one of the few companies to take Amstrad seriously when it first appeared on the scene back in 1985.

Atari president Sam Tramiel, son of Commodore founder Jack, had said in the spring of 1986, as the company was launching its CP/M and IBM PC emulators, that he had been "amazed by what Amstrad has done in this [word processing] field" in the UK[7], but now it was aiming directly at Amstrad's market.

Whilst both companies' PCs were retailing at around $799 (£570 in the UK, or around £2,090 in 2025), Atari had the advantage of EGA graphics, switchable CPU speeds (the legendary "turbo" button of the 80s and 90s) and increasingly importantly, Microsoft mouse compatibility - all of which were said to make Atari's compatibility a lot more complete than Amstrad's.

However, the even bigger news was Atari's laser printer.

By stripping out the raster processing/imaging engine and running it in software on the Atari ST instead, the company managed to break the £2,000 barrier that laser printers had been languishing at by a long way, with an expected price of only £1,071[8] (£3,920 in 2025).

This placed Atari in a potentially Apple-Mac-busting position in the desktop publishing market.

Date created: 07 July 2014

Last updated: 11 December 2024

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2025. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.