Intel Advert - December 1993

From PC Review

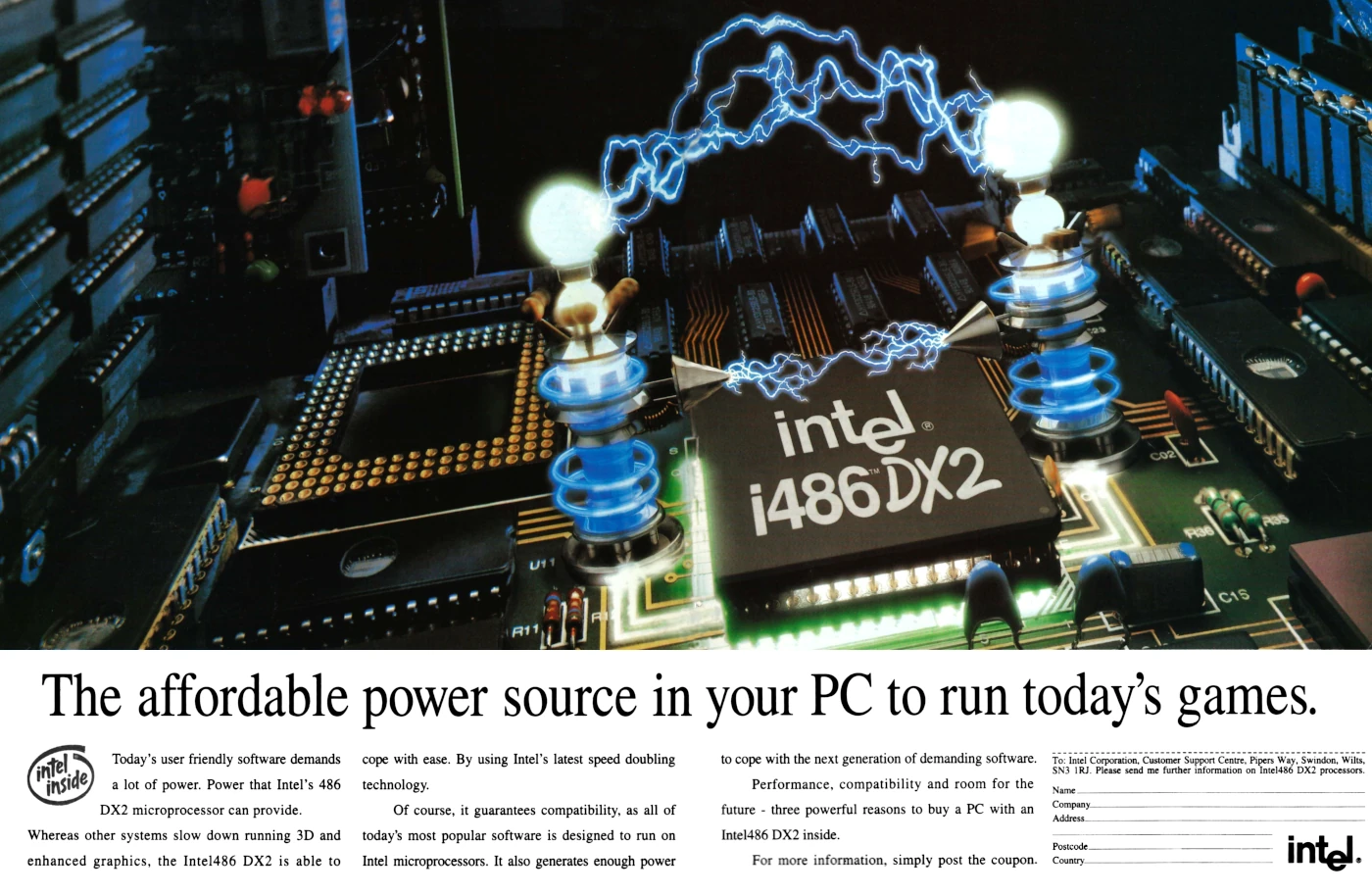

The affordable power source in your PC to run today's games.

Intel didn't do a huge amount of advertising, seeming to prefer to allow word-of-mouth, or inertia, to do its selling.

In the early 1970s, it had the hobbyist and microcomputer market - such as it was - mostly to itself, which was perhaps fair enough as it was credited with inventing the first commercial microprocessors - the 4004 and the 8008.

However Chuck Peddle, co-designer of the 6502 and sometimes referred to as the "father of the PC", disagrees with this as he considered the 4004 and 8008 as nothing more than calculator chips, suggesting that Motorola's 6800 was the first true microprocessor[1].

However, Intel continued with updated models and ended up setting an early standard with its 8080, then 8085 - a 5 volt version which was cheaper and easier to build around.

Then, in 1974, Intel employee - and co-designer of the 8080 - Frederico Faggin left to start rival chip company Zilog, which launched its 8080-compatible-but-much-cheaper Z80 in 1976.

The Z80 was one of two processors, along with MOS Technology's 6502, which came to dominate the home computer market through to the mid 1980s, however whilst the Z80 was also popular in business machines, at least at the budget end of the market, Intel remained a constant presence.

That presence became more of a dominance after IBM chose the Intel 8088 - a version of Intel's latest 16-bit 8086 chip which only had an 8-bit data bus - for its 5150 PC, launched in 1981.

This machine - better known as the IBM PC - defined the industry for a couple of generations, with various iterations of the same x86 architecture - the 80186, 80286, '386 and the chip of the advert - the 80486 - appearing in not just IBM's PCs, but more significantly the millions of clones of it that followed.

Meanwhile, AMD - a company founded in 1969 as one of several spin-off "Fairchildren" to come out of Fairchild Semiconductor - had been quietly manufacturing memory chips and working as a second-sourcer for companies like National Semiconductor and, later on, Intel itself.

This came about because IBM required that there was a second source of chips for its 5150 PC, and so a contract was signed in 1982 between the two companies, with AMD going on to produce 8086, 8088, 80186 and 80286 chips under licence.

At some point, AMD started branding its 80286 copy as the Am286, but annoyingly for Intel it was producing them with higher clock speeds than the original, a situation which started to affect Intel's bottom line.

So by the time the 80386 rolled around, Intel decided to exclude AMD from its latest design, with AMD taking over five years to reverse engineer it. When it did finally release the Am386, it once again showed it could produce chips with faster speeds[2].

The pattern continued right through to the release of AMD's Athlon processor at the end of the 1990s - considered as AMD's zenith - matched all the while by a declining market share for Intel.

Intel was annoyed enough about the situation that it started asserting one of its little-known patents towards the end of 1992.

In a move targetted primarily at chip cloner Cyrix, as well as AMD, and branded as an illegal "extortion scheme", the 1990 patent covered any PC which used Intel's microprocessor design in conjunction with any multi-tasking operating system - potentially affecting all the one million Windows PCs shipping per month at the time.

Intel was asking $25 royalty per 486 computer shipped, or $15 per 386, with the royalty unsurprisingly waived if the computer was using an Intel chip.

AMD UK's managing director David Brand considered that AMD's existing cross-licencing deal was enough to cover it, whilst Cyrix claimed that as it had an agreement with SGS-Thomson - itself a licenced second-sourcer of Intel chips - it was also covered.

That didn't stop Cyrix's president Jerry Rogers from branding Intel's move as "outrageous", whilst the company was taking steps to launch a second anti-trust action against Intel[3].

Eventually, poor management, an over-valued buyout of graphics board maker ATI, and Intel's continuing monopolistic behaviour in paying PC manufacturers to keep AMD chips out - part of which involved paying towards a company's advertising if it used the "Intel Inside" branding - led to something of a downfall for AMD in the first decade of the 21st century.

A few months later, Intel announced that its profits had passed $1 billion for the first time.

Based on revenues of $5.8 billion - up 22% from the year before - it placed the company as the number one semiconductor vendor in the world, ahead of Japan's NEC.

It also marked the moment when Intel expected 486 and 386SL shipments to exceed those of its older 386 line, at least in Europe - AMD had yet to release a 486 clone, although this was expected by the middle of 1993[4].

Meanwhile, the advert itself - which perhaps represents part of Intel's reaction to increasing competition from AMD - is notable for a couple of other things.

First, the 486 marked the end, at least in the PC world, of the separate maths co-processor - a chip which was often available as an optional extra to go along with early processors (e.g. the 8087 went with the 8086) in order to improve a computer's ability to work with floating point numbers - as the 486 effectively contained its own on-board maths co-processor.

And secondly, the advert also shows how the games industry was by now driving the PC business as much, if not more, than business software.

Processor power had long since exceeded the requirements for spreadsheets and word processors, but games would make as much use of processor power as there was available, and then some.

For many years, Microsoft's Flight Simulator was both a benchmark for how compatible a PC clone was to a "real" IBM, and for how well it performed overall.

PCs as gaming platforms continue - along with AI more recently - to drive PC development, especially graphics cards, today.

Date created: 17 March 2025

Last updated: 09 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.