Pace Advert - 4th May 1984

From Personal Computer News

Is the information revolution passing you by? Nightingale - The Modem

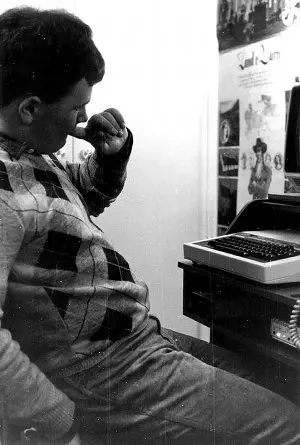

A Nightingale modem in action in 1984 or 1985, connected to a BBC MicroThe mid-1980s - 1984 to 1986 in particular - were notable for the destruction that swept through the microcomputer industry, with companies like Dragon Data, Camputers, Enterprise/Elan, Oric, Jupiter Cantab, Acorn and Sinclair either going to the wall, being bailed out or being sold for assets and name.

They were also notable as being the era of the explosion of dial-up in the UK. De-regulation of the telecoms market following the privatisation of BT had lifted onerous restrictions which only a few years before had required the written permission of the local Post Office branch if you wanted to even attach a modem to a phone line[1].

Several companies were now supplying ready-to-go British Approvals Board for Telecommunications (BABT)-approved modems which could be simply plugged in for access to Micronet, Prestel, Bulletin Boards (BBSs) or even exotic dial-up networks like Compuserve and The Source in the U.S.

Pace was one such company - its Nightingale model was aimed at the BBC Micro as well as Apple, ACT and IBM, and unlike many of its 80s peers, was a relative success story that made it through to 2014 as an independent £multi-billion company[2], specialising in modems of the broadband variety as well as set-top boxes, before being acquired by US-based Arris in 2015 for $2.1 billion in cash and stock[3].

The Nightingale was not cheap, retailing at £136, or £159 with the software to drive it (about £690 in 2026 money), but the world that it and its ilk opened up felt space-age, pioneering and amazing.

Connecting to the big databases and bulletin-board systems in the US wasn't always an un-achievable fantasy, even if you weren't a phone phreaker capable of spoofing the telephone network using multi-tone key-pads to get free international dialing[4].

In the autumn of 1984, Dialog Information Services set up a UK portal of its service called Knowledge Index. Offering access to 20 databases with more than 20 million summaries of newspapers, books, programs and technical reports, the service used British Telecom's new-ish Packet Switch Stream service to route calls via one of 18 regional PSS numbers.

Although it was restricted to cheap-rate hours (6pm to 5am) it was relatively cheap at $24 per hour, or around £69 in 2026 money[5].

It was also possible to use PSS to connect to other services in the US and around the world, for much less than the price of direct-dial, by contacting the PSS Customer Service Group and requesting a network user ID.

Then, armed with a series of arcane command-line instructions, you could be on a network in Brazil or Australia in no time, at a far-more-affordable hourly cost of £6 - plus data charges[6].

Even so, such was the cost of peak-rate dial-up that Micronet ran a section called the "Midnight Micronetters Club" and the Prestel Hackers - Schifreen and Gold - pointed out that even hackers wouldn't start until cheap rate at 6pm, which was handy as that was generally when the ite'>IT and admin staff of their chosen targets had all gone home for the day.

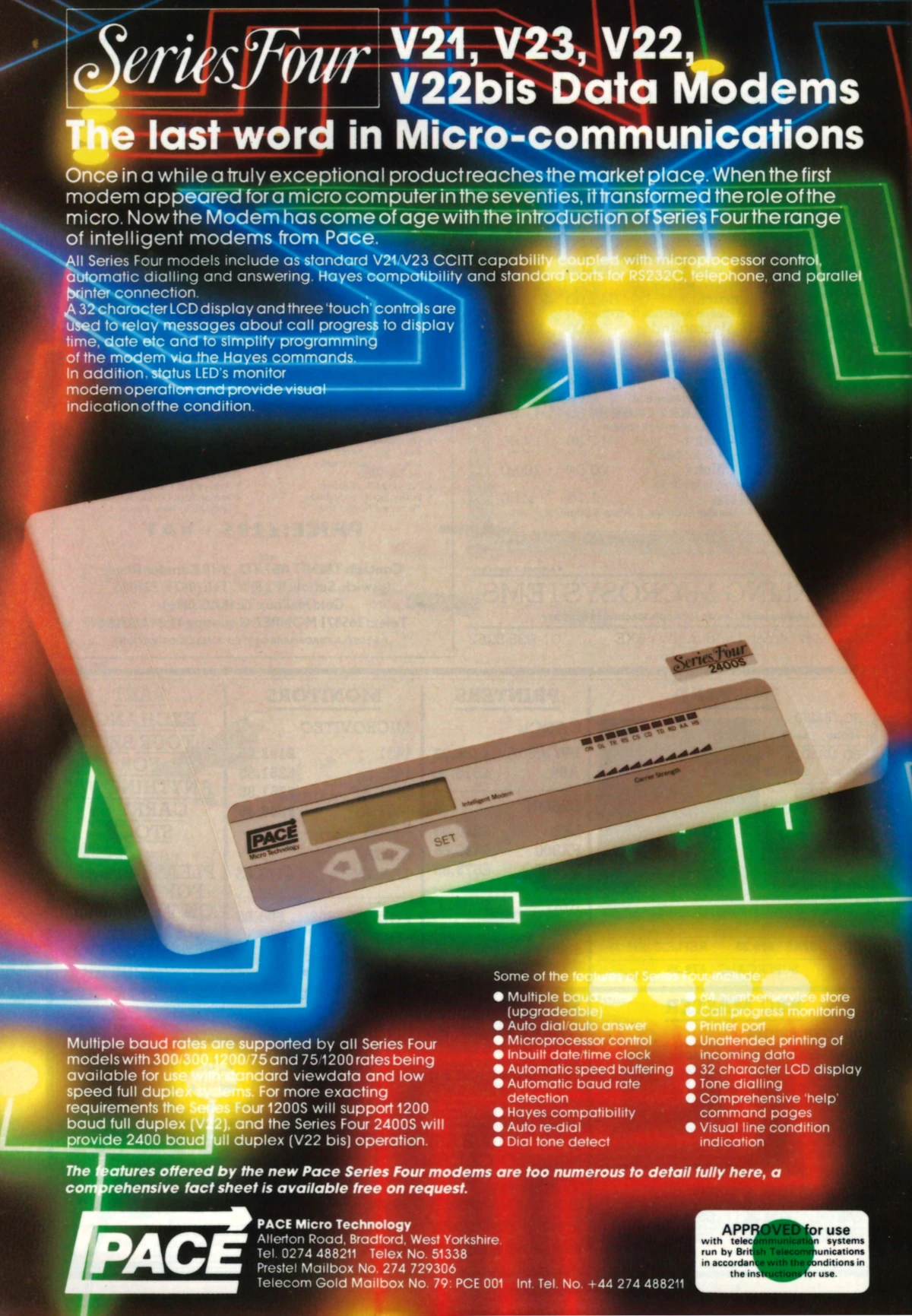

itle="An especially-colourful 1987 advert for Pace's Series Four modem, showing that the technology has come a long way in just a few years. The Series Four 2400S supported up to V.22bis 2400 Baud/bits per second, as well as the older 300 Baud V.21 and V.23, the Prestel/Viewdata standard. From Personal Computer World, July 1987.">

itle="An especially-colourful 1987 advert for Pace's Series Four modem, showing that the technology has come a long way in just a few years. The Series Four 2400S supported up to V.22bis 2400 Baud/bits per second, as well as the older 300 Baud V.21 and V.23, the Prestel/Viewdata standard. From Personal Computer World, July 1987.">An especially-colourful 1987 advert for Pace's Series Four modem, showing that the technology has come a long way in just a few years. The Series Four 2400S supported up to V.22bis 2400 Baud/bits per second, as well as the older 300 Baud V.21 and V.23, the Prestel/Viewdata standard. From Personal Computer World, July 1987.

Although it was now easier to get approval for a modem, it didn't mean that the process was anything like speedy.

By 1987, things were bad and many companies were becoming increasingly frustrated at the staggering amount of bureacracy involved, which included sending every modem to a lab for testing and even involved visits to the manufacturer's factory to check that it was up to standard. John Vevers of BABT explained that

"We have to work to the standards and regulations laid down for us, and we must operate in accordance with government policy. We have had difficulties in recruiting professional engineers because of national shortage. I would like to provide a speedier service but it's not easy".

The problem for manufacturers was not just the presence of the dreaded pre-approval red triangle, which unlike the coveted green square meant that whilst it was legal to be sold it was illegal for the buyer to actually plug it in, but more importantly the fact that by the time a modem had been approved it was most likely out of date.

As Nazir Jessa of Watford Electronics said, with some understatement:

"The industry moves so fast, that by the time it is approved we will have a new and better modem ready. [Our unapproved] Le Modem is currently on sale but its red triangle is seriously affecting sales".

Barry Krite of Datastar Systems was even more downbeat, explaining that the company had sent its Magic Modem off for approval, but "unless it gets through soon, the factory will have to close"[7].

There was some relief for modem manufacturers when the British Standards Institute (BSI) announced in April 1987 that it was opening a "while-u-wait" testing service at its Hemel Hempstead telecomms laboratory.

The service, which, according to the BSI, covered all the "signalling, spectral and electrical requirements" of various British Standards, meant that in theory it would be possible to almost fully-test the performance of modems, telephones of new-fangled fax machines in one day, the results of which would be sufficient to fulfil BABT testing requirements.

BABT itself wasn't entirely convinced that it was physically possible to do all the regulatory testing within a day, whilst acknowledging that a significant blocker was actually in manpower - it was in the middle of a recruitment drive having opened its own new testing facilities at Harlow and Kingston-upon-Hull - but was still supportive of the new service.

BABT's Barry Cartman suggested that "any arrangement by any test house that moves in the direction of shortening the time taken for testing" would be a Good Thing[8].

In an echo of the early 1980s micros-into-schools programs, the DTI had announced back in February 1986 that it was bunging £1 million towards buying Tandata 512 or Dacom 2123 AD modems for every secondary and middle school in the UK, with a provision for access to the DTI's own National Educational Resource Information Service (NERIS) database, as well as commercially-sponsored Prestel and access to The Times Schools Network.

A DTI spokesdroid suggested magnanimously that "Any that are left over will go to independent schools and teacher training centres"[9].

At about the same time, Pace introduced a serial interface and communications software for Acorn's Electron. The software came on a plug-in chip and came free if the whole bundle, which also included the Nightingale modem, was purchased for £139, or about £540 in 2026.

As Acorn was in the process of stock-dumping Electrons to shift a huge warehouse surplus, the micros were retailing for less than Pace's bundle, however the combination still made for a very cheap Prestel or Telecom Gold adapter, a situation which - according to Personal Computer World - Pace was "exploiting nicely"[10].

Date created: 27 February 2014

Last updated: 23 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.