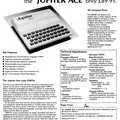

Jupiter Cantab Advert - May 1983

From Practical Computing

The Jupiter Ace: Clever enough for Forth, dumb enough to sell for £90

The Jupiter Ace, launched in August 1982, was an unusual entry into the canon of early 1980s British home computers.

Although it was Yet Another Z80 Machine, it was different in its choice of Forth as a progamming language, making it - according to the advert - ten times faster than an equivalent BASIC machine.

Claims of speed were indeed backed up in reviews, with Your Computer calling it [the] Speed Machine.

It was also unusual in having no sound and being strictly monochrome which, in the era of the Commodore 64, BBC Model B and the Sinclair Spectrum, might have been considered something of an oversight.

In his review in January 1983's Personal Computer World, Mike Curtis wrote presciently:

"it does not have colour and with the price of colour machines dropping fast this could turn out to be a big disadvantage"[1].

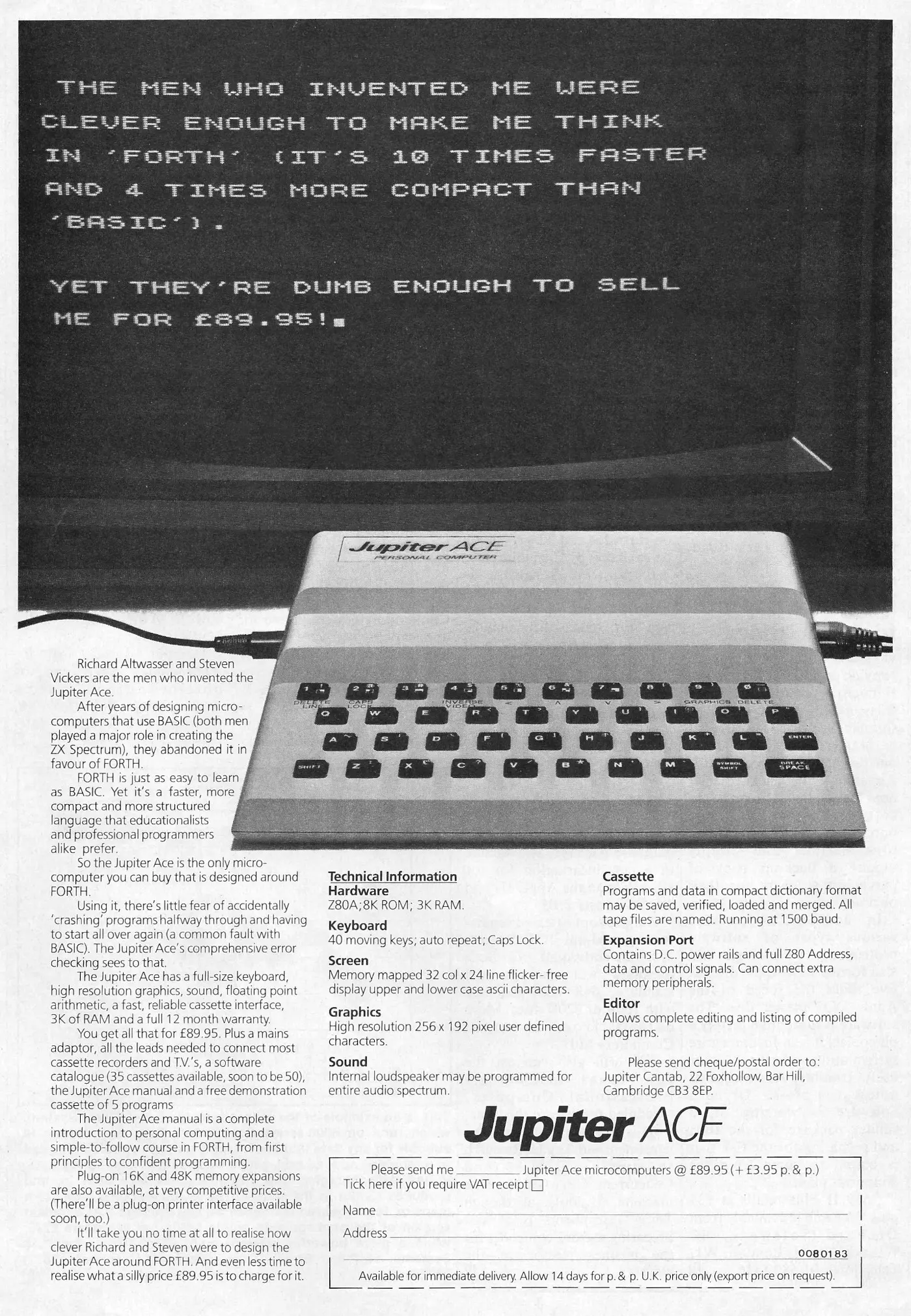

Steve Vickers, © Popular Computing Weekly, 19th August 1982It came out of a company set up by two Cambridge engineers ("Cantab" is a diminutive of the Cantabrigian moniker by which residents of the town or alumni of the university are known) - Richard Altwasser and Steven Vickers - both of whom had worked for Sinclair.

Altwasser had joined Sinclair when the ZX81 project was well underway, but nevertheless contributed the design of the 81's printed circuit board.

He was made responsible for computer development and became the primary designer of the Spectrum, when that project was kicked off towards the end of July 1981.

Vickers, meanwhile, wrote a large part of the Spectrum's ROM as well as its user manual.

The lack of colour for the Ace was therefore particularly surprising, as when interviewed about the birth of the Spectrum he recounted discussions about its design in which he said:

"we decided it must have high-resolution graphics..., sound, and of course most importantly colour"[2].

Not only that, but the company that Altwasser and Vickers formed after leaving Sinclair was provisionally called the "Rainbow Computing Company".

The Ace's advertised price of £90 (£440 in 2026 money) was very competitive, but its lack of colour and relatively-obscure choice of programming language kept it the preserve of hardcore programming nerds.

It also didn't help that its "unique selling point" - the Forth language - was becoming available for other computers by the end of 1982, including for free with every "full-size" Oric, and for only £15 on the BBC Micro[3].

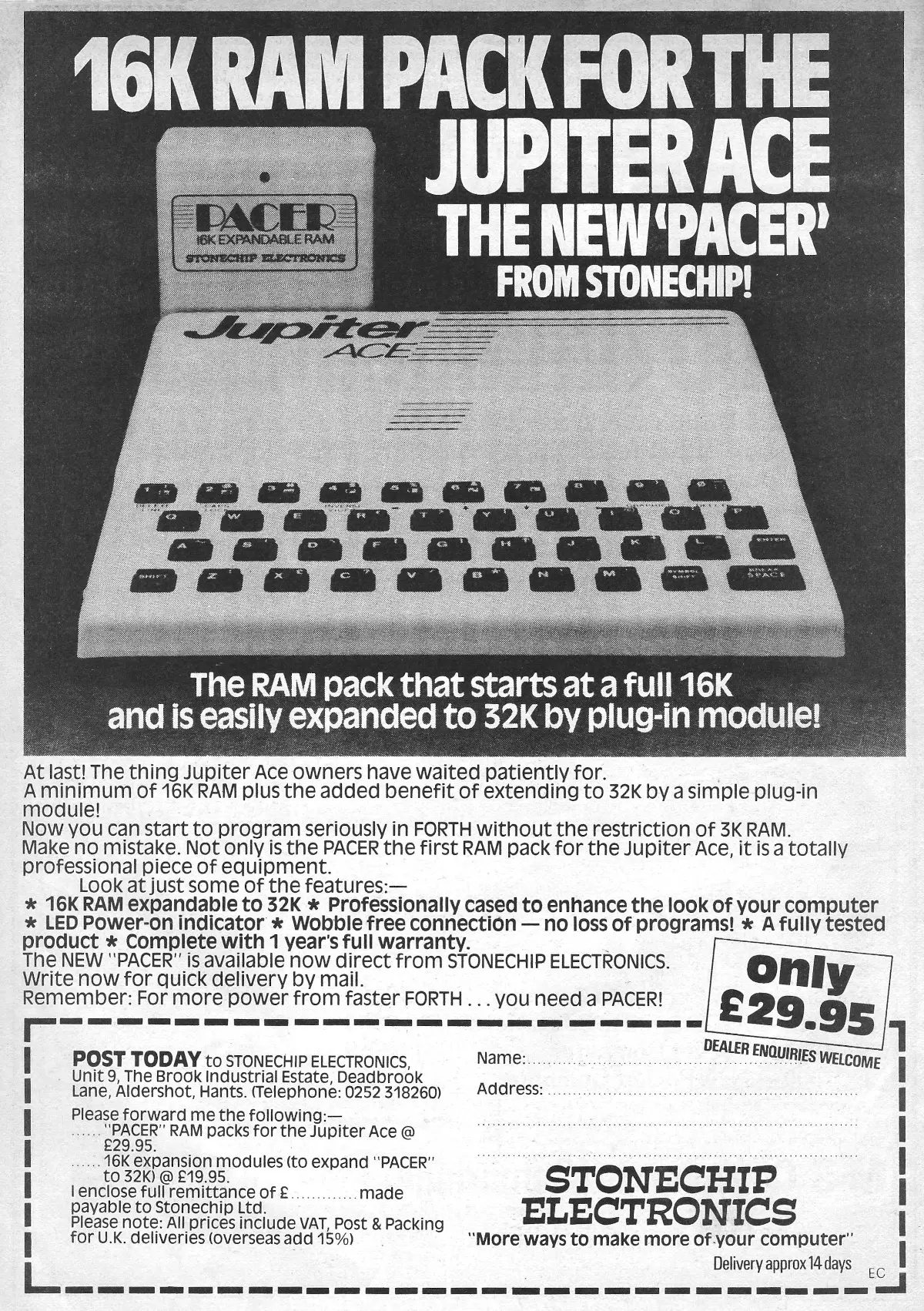

Despite not selling hugely, there were some third-party add-ons available for the Ace, including this expandable RAM pack from Stonechip Electronics. From Electronics and Computing Monthly, April 1983

There was even the threat of a more direct competitor to the Ace, when Microkey announced in July 1983 its plans to build a Forth machine with a specification that was to be determined by user requests, albeit with a pre-determined choice between two processors - the MOS/Commodore 6502 or Motorola's 6809 - either of which could be plugged in.

The company, set up by Advanced Text Systems, originally punted the idea in an advert which appeared in Personal Computer News.

According to managing director Paul Wynter, the company "had no idea what kind of response we would get from the advertisement" but that it reckoned "that if we got more than 500 responses there was a 'go' situation".

As it happened, there were more than 1,700 replies and all were sent a follow-up questionnaire asking what sort of machine they wanted.

A large number of these turned out to be from schoolchildren, many of whom were critical of their existing machines, which included Research Machines' 380/480Z, Acorn's BBC Micro and Sinclair's ZX81 and Spectrum.

Wynter was "amazed at the level of computing knowledge of many of these young people"[4].

The Sinclair connection was not lost on reviewers of the Ace.

Writing in November 1982's Your Computer, Bill Bennett noticed several things that would be familiar to a Sinclair owner - a missing power supply with the review model (a Sinclair one was used instead), a very similar user port, the ability to use a Sinclair 16K RAM pack, and even the case design.

He also concluded that "the machine's development is certainly a brave gamble on behalf of its manufacturers", but that "it will be of great interest to scientists, those with control applications [and] ZX81 machine-code fans"[5].

In the summer of 1983, the company was trying to improve its image by demonstrating the Ace's use in robotics control, in conjunction with Cyber Robotics, at the June 1983 Computer Fair in Earls Court.

It also launched a "new, prettier box to replace the floppy plastic of the earlier models" and had bought in some new management, in the shape of Geoffrey Walker, to what was seen as a formerly amateur company.

It was also hoping to break into the US, and so was beefing up the machine's specifications, which included additional radio interference suppression to comply with tighter FCC regulations, and a more serious range of scientific software[6].

It was not to be though. Jupiter Cantab crashed in November 1983 and three months later the liquidator had still failed to find a buyer for the manufacturing rights.

The company had only sold about 9,000 units in total, of which 800 were in the US, where it was known as the Ace 4000[7].

Jupiter's assets, including the remaining 2,000 Aces, were bought by Boldfield Computing of Cambridgeshire, which planned to sell the micros by mail order for £29.90 (£130 in 2026), with Paul Downham of Boldfield stating that would initially be offered through computer clubs before the company considered any wider advertising.

Boldfield had no intention of actually taking up manufacture of the machine[8].

That might have been the final chapter in the Jupiter story, however there was some excitement when several years later a stash of these "long extinct" Aces was re-discovered in Boldfield's Hobson Street branch in Cambridge, which was selling them off for £35 a go - about £140 in 2026[9].

Boldfield had been producing and selling accessories for the Ace, such as a joystick interface and a "ZX81 adapter", during the previous year.

Even then, it had had to scour the market to track down further supplies of the elusive machine, which it was previously selling for only £26 (£110) - less than the cost of the components and cheaper than a copy of Forth on a disk[10].

Relative minnows of the computer world Jupiter Cantab Ltd went in to receivership in the same week as the whale - or shark, if you were Commodore's Jack Tramiel - that was Texas Instruments announced that it was exiting the consumer and home micro market, thanks mostly to Commodore's price war, so at least it was in good company.

Popular Computing Weekly was one magazine which, whilst recognising that the collapse was perhaps not entirely unexpected, suggested that it was still a blow to the UK micro industry.

It also offered something of a eulogy for the defunct company, suggesting that the industry would be poorer for the loss of Vickers and Altwasser:

"While the Jupiter Ace may not have captured the public's imagination in quite the same way as its ZX brethren, it was a brave attempt. Both Vickers and Altwasser deserve our approbation for seeing an opportunity and trying to make it work. There is an element of risk in any entrepreneurial operation - but it is better to try and fail than never to try at all and spend the rest of your life wondering 'what if'?"[11].

The decision to wind the company up had been taken by Jupiter's directors, which duly called a creditors' meeting and instructed its solicitors - Chater and Myhill - to prepare a statement of affairs.

First real signs of a problem had occured back in early June 1983 when Altwasser resigned his directorship and left the company.

Vickers, who remained, then tried to steer the company towards the schools market, where it was thought the Ace might be more popular as a Forth-based teaching machine.

Interest in Forth had been growing, but one of Jupiter's problems was that many other machines were getting their own versions of the language.

On the other hand, the Ace could not run BASIC, which further restricted the availability of good software.

Elsewhere, one source had suggested that another reason for the failure of the company was "management weakness"[12].

Date created: 01 July 2012

Last updated: 29 January 2026

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.