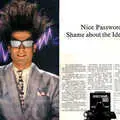

Micronet Advert - June 1985

From Your Computer

Micronet 800: Nice password, shame about the identity

With an advert containing a theme still relevant to a modern audience - "your special identity number and personal password [are] the valuable key to a huge database" - Micronet 800 was a subsection of Viewdata dial-up system Prestel, with a particular focus on personal computers, international Telex, bulletin boards and email.

The Prism connection

Micronet started out life as a loss-making Prestel project within publishing and printing house East Midland Allied Press, or EMAP.

Richard Hease, founder of the computer magazine Practical Computing and now the owner of ECC - the publisher of Educational Computing and partner in modem manufacturer Prism Microproducts - became involved with the project after ECC had sold some of its publications to EMAP. He was given the job of making the service pay its way or to close it down.

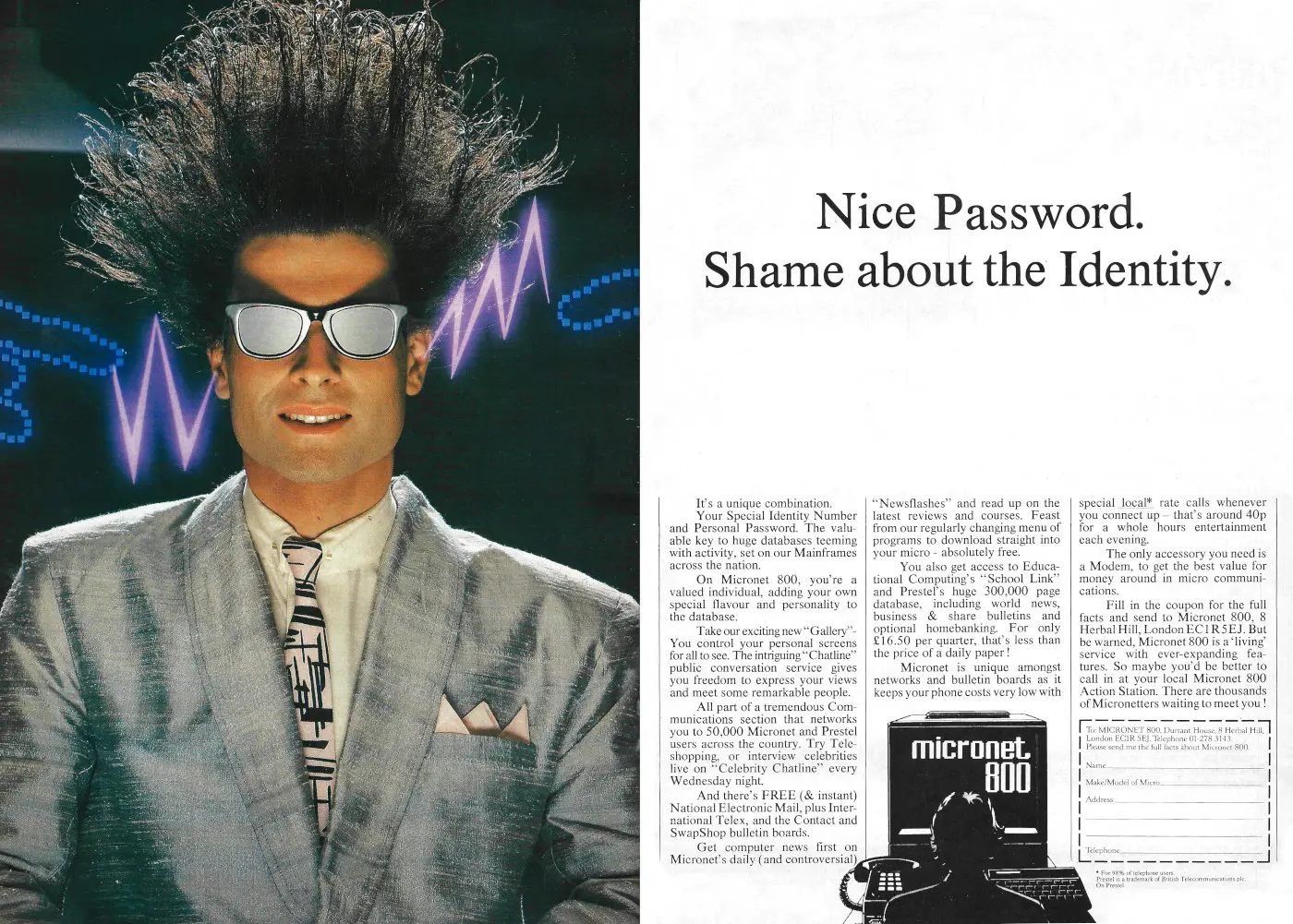

Richard Hease (far left) helps judge Practical Computing's Christmas 1978 competition, along with fellow Practical Computing staff Dennis Jarret and Wim Hoeksma, along with Mike Sterland of Personal Computers Limited

Hease came up with the idea of providing a computer user's database, offering telesoftware, news and on-line shopping, and managed to get the backing and investment of both Prestel and the Department of Industry, with the whole thing coming together within a matter of weeks. Hease was impressed, stating that:

"both Prestel and the DoI moved faster than I've ever seen a government or bureacratic organisation move".

Bob Denton of Prism, © Popular Computing Weekly, September 1983Meanwhile, Bob Denton, former cash-register manufacturing company employee, had switched industries to become UK marketing manager for Texas Instruments, during which time he oversaw the launch of the ill-fated TI-99/4.

He then moved on to help launch Mattel's Intellivision before becoming involved with Tandata's also-failing Prestel operation, and after that went on to become Dragon's director of Sales and Marketing.

In April '82, Denton launched a Prestel-based electronics magazine called Electronics Insight and subsequently met Hease, whereupon the two realised their shared interest in Prestel networks.

In June 1982, EMAP's Prestel division, known as Telemap Group, and which was already a top-20 Prestel information provider thanks to its 60,000 accesses per month from 18,000 users, bought up Electronics Insight and the two systems went on to form the basis of Micronet 800 - the 800 being the page number in Prestel where the service was originally located[1].

Their combined 3,000 Prestel pages quickly increased to 30,000, thanks to 28 London-based full time staff and 30-40 home workers, in time for the service's 1983 New Year's Eve launch. Later on, everything moved on to a GEC 4082 mainframe which allowed the service to support up to 120,000 additional pages, if it needed to.

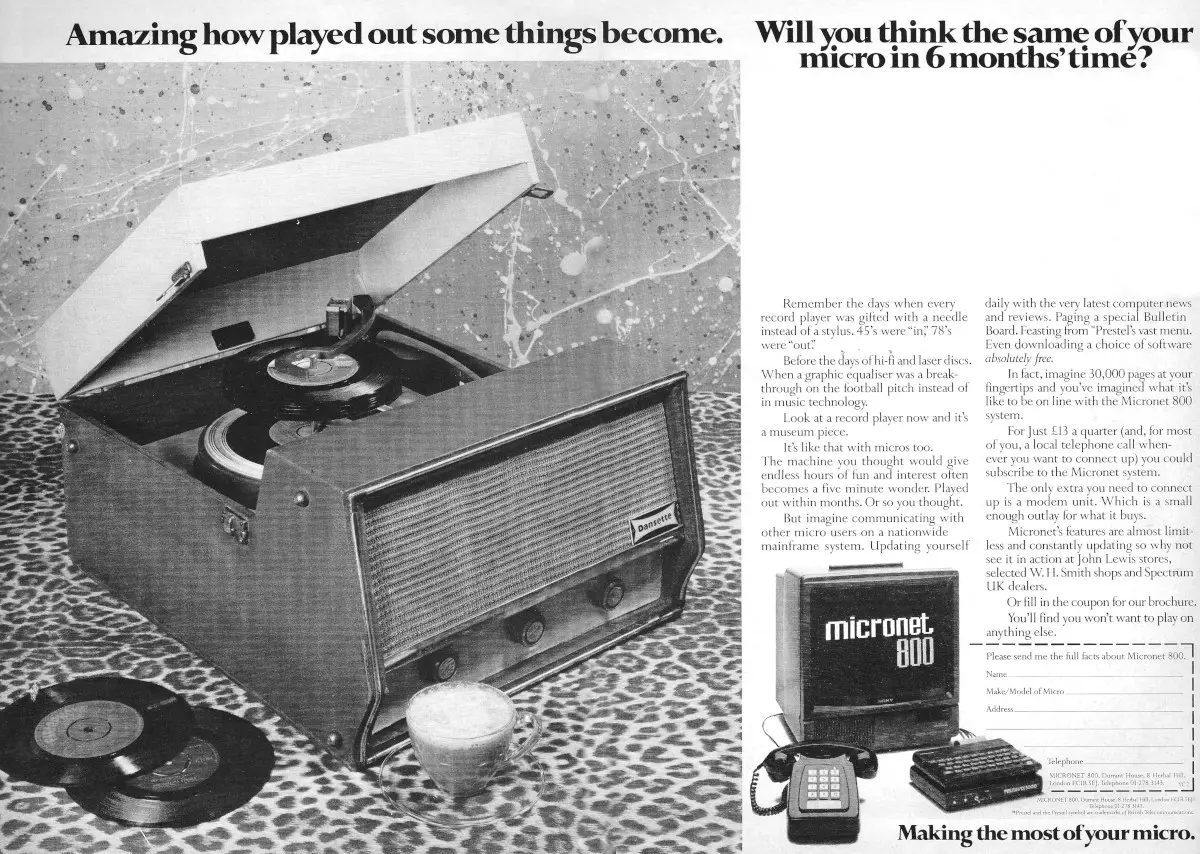

Another Micronet advert, from July 1984's Your Computer - featuring a Dansette record player

Prism was in a useful position to do something about one of the biggest problems holding back the service - the lack of adapters.

It had made its name when it was appointed, only seven weeks after it had been founded, as the sole distributor for Sinclair, and was already planning to move into other software and hardware.

Moving on to also manufacture Prestel adapters and modems - for "every micro [with] a population greater than 25,000", according to Denton - was therefore a fairly natural progression, especially given Denton's time at modem-manufacturer Tandata.

It had big plans too, which it was expecting would cost the Micronet Consortium - Prestel, EMAP, ECC and Prism - around £3 million to get started and another £500,000 per year to keep it running. Denton said of this that:

"We are probably not going to make a big profit in year one. What we have to do is make it as painless as possible to join and to provide a wide range of services".

At the time it was selling more than 350 ZX81s per day, but perhaps Denton was getting a little carried away when he stated:

"Our privileged position with Sinclair to some extent will make Prism the arbiter of which add-ons and software are and are not bought. Prism has both ends of the market and intends to become very much a force to be reckoned with"[2].

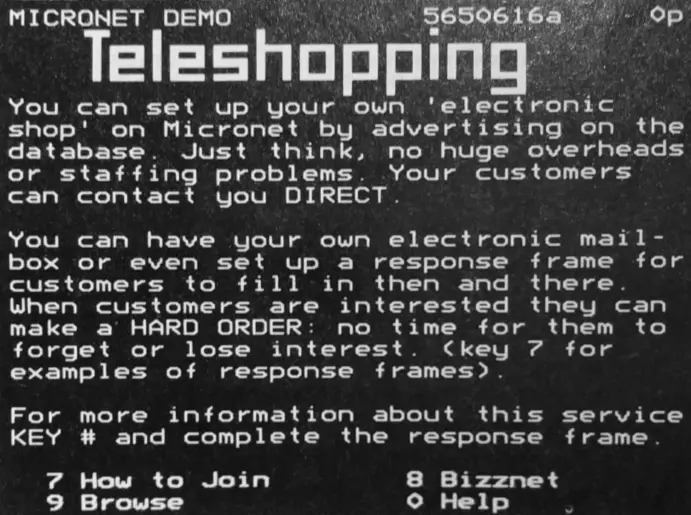

Micronet demonstration of teleshopping in 1988, © Personal Computer World February 1988The service was unveiled in the summer of 1982 and although it had been planned to launch on January 1st 1983, it didn't technically open until February 21st.

It fully launched publicly in March 1983 and within two months was already using half of its initial maximum allocation of 30,000 Prestel Frames of data, with over 1 million accesses in April alone[3].

It was hoping to reach its target of 12,000 users by the end of 1983 and was running at the rate of 1,000 subscriptions a month since its very first user - estate agent Jeremy Dredge - had logged on[4].

Although it wasn't the first part of Prestel to be aimed specifically at microcomputer users - that accolade went to the Amateur Computer Club's ClubSpot pages - it did become the largest, to the extent that it became so important to Prestel's overall subscriber base that Prestel eventually invested directly in it, rolling it up with ClubSpot and ViewTel into a single area called, unoriginally, "Prestel Microcomputing".

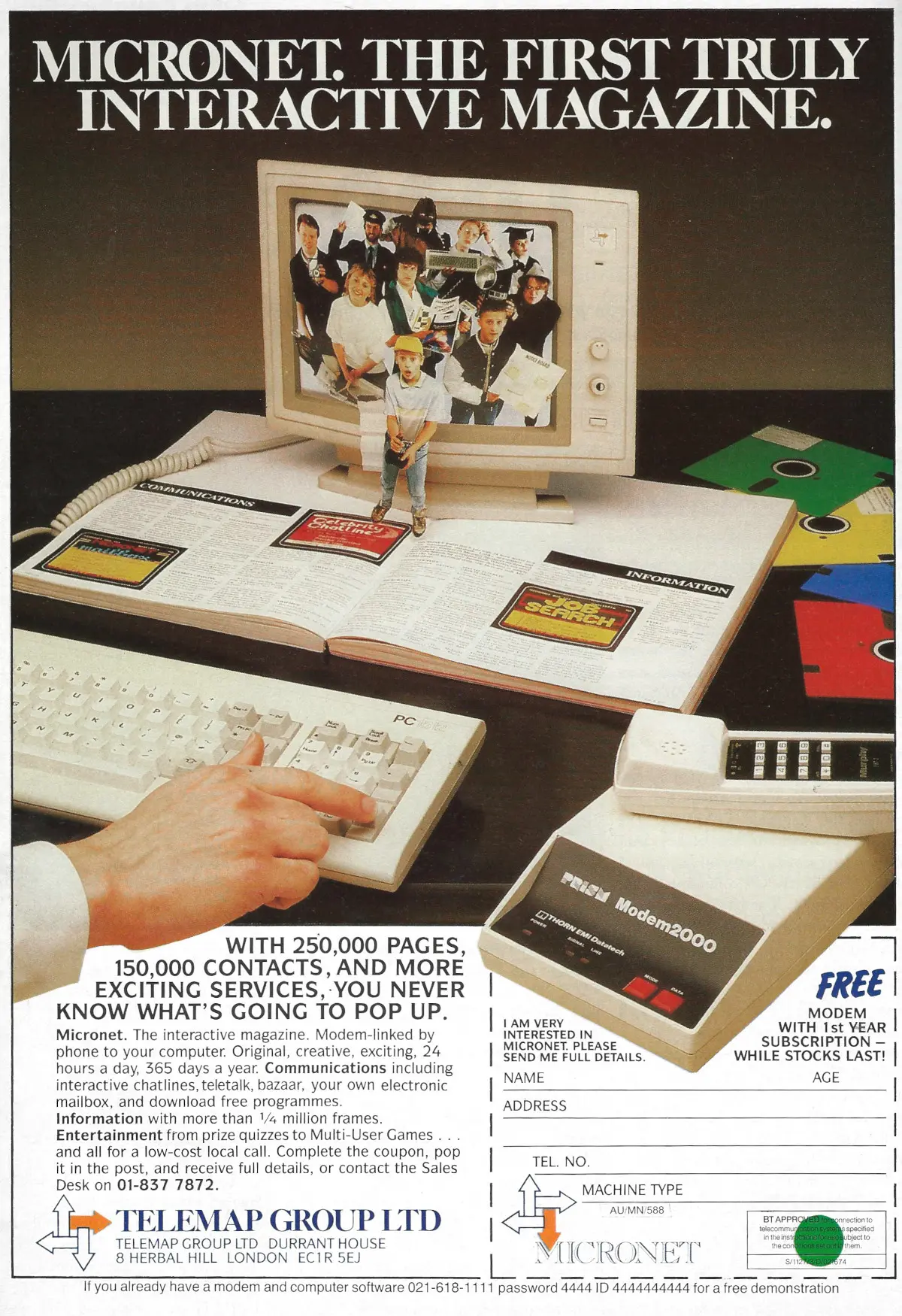

An advert for Telemap Micronet - the first truly interactive magazine - and featuring a Prism Modem2000, now built by Thorn EMI Datatech following the collapse of Prism itself. From Acorn User, May 1988

By the time of its fifth birthday in March 1988, it was up to 50,000 pages - nearly a sixth of the whole of Prestel.

Prism, however, had been defunct for three years, having gone bust in 1985, and so it appears that Micronet had returned to the fold of the Telemap Group.

Date created: 08 December 2019

Last updated: 29 July 2025

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2025. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.