Enterprise/Elan Advert - April 1985

From Your Computer

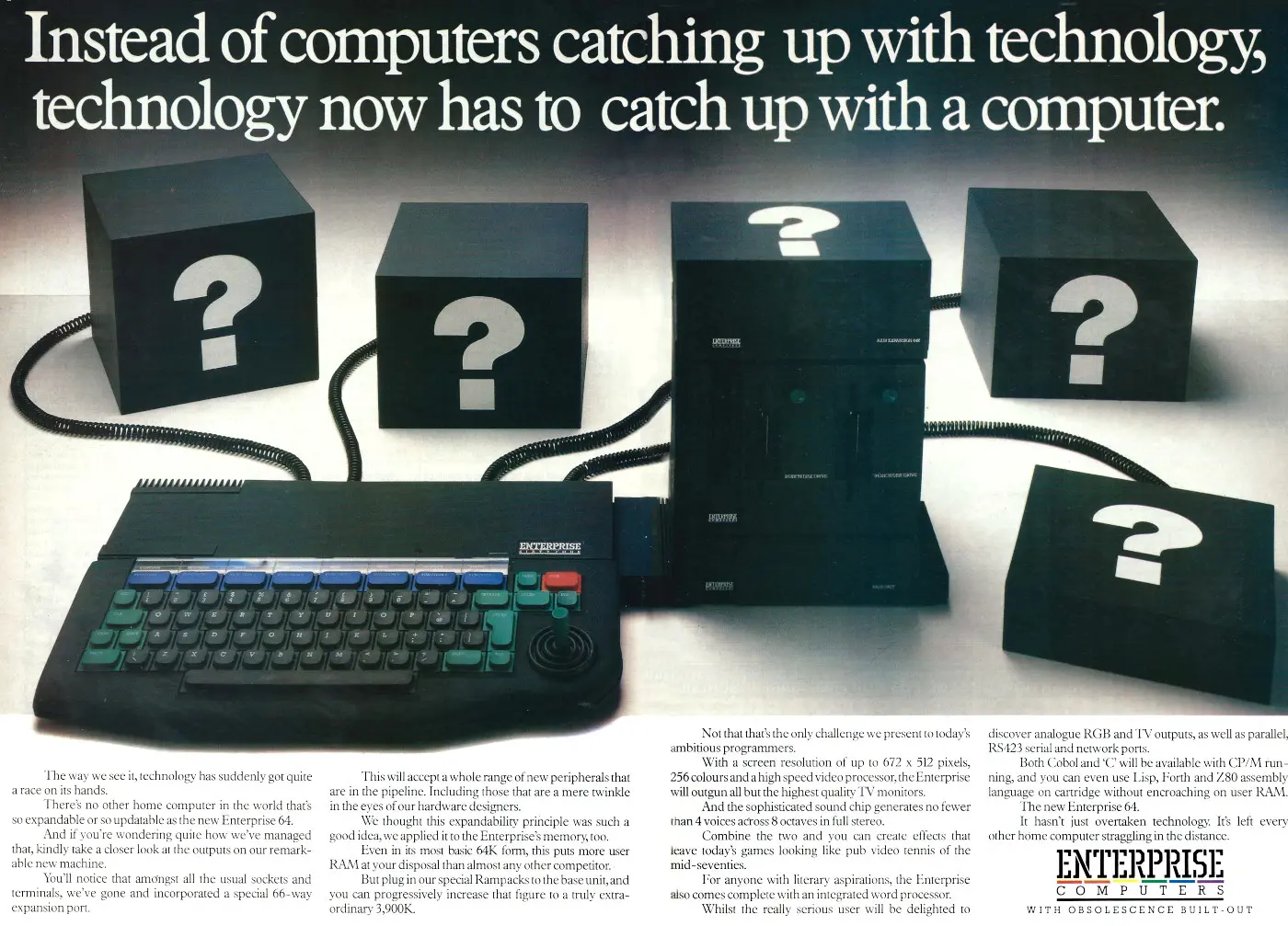

Instead of computers catching up with technology, technology now has to catch up with a computer

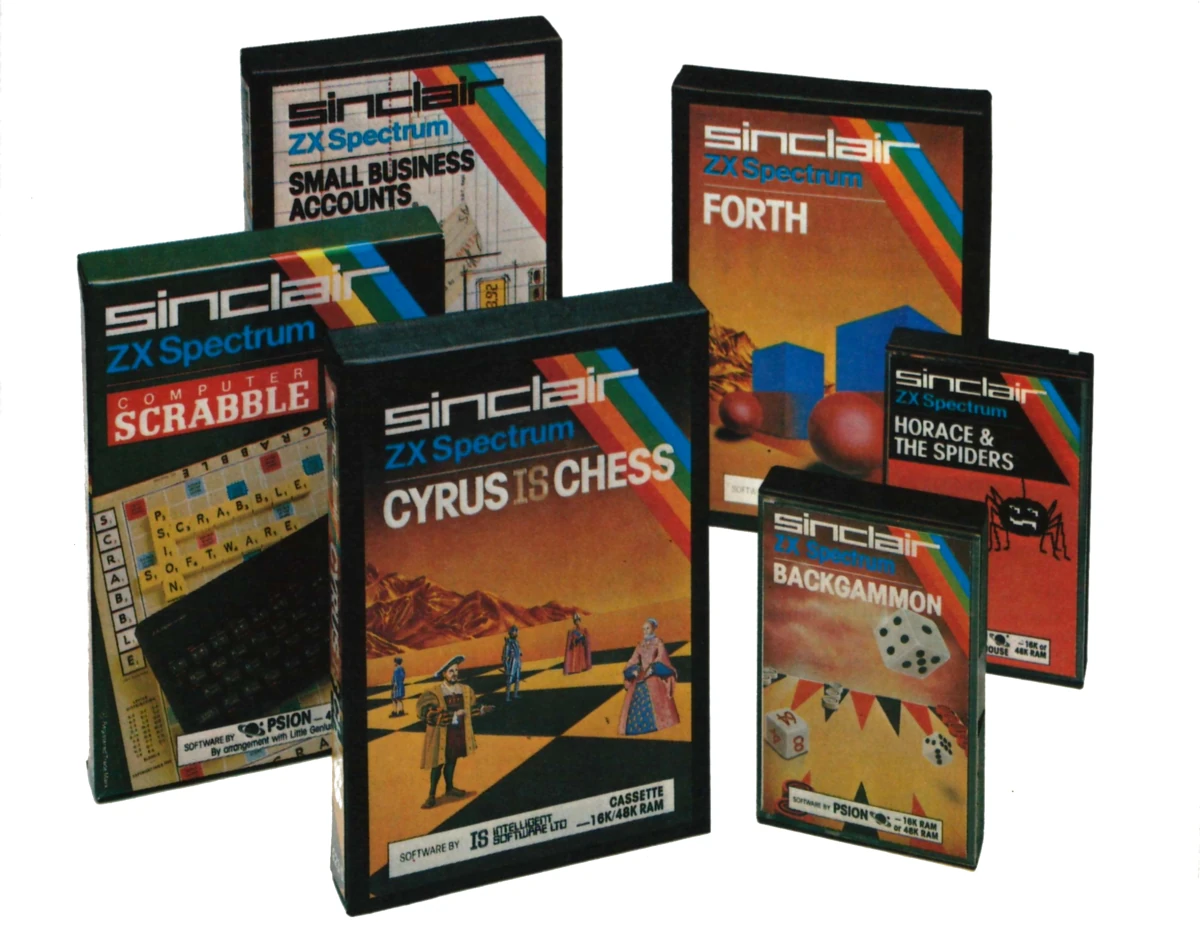

In the summer of 1982, one-time Olympic chess player[1] and former chess grandmaster David Levy, of Intelligent Software - a company best known for producing programs like Cyrus IS Chess, written by Richard Lang, but with a strong track-record of designing chess hardware - was approached by a "mystery backer" who wanted a rival to the ZX Spectrum, which had only recently been launched.

Just another Spectrum?

The un-named mystery backer was initially referred to as an "international finance consortium", but was later revealed to be Domicrest, a Hong Kong electronics company.

Domicrest wanted Intelligent Software to design a machine[2] that was initially intended to be a PDA-style pocket calculator device[3].

Also according to Robert Madge, a director of Intelligent Software and who became technical director and team leader of the project, such a machine should:

"still be wanted four or five years after the original design decisions were taken ... and ... seduce people in to buying the machine yet say a little about the technology".

The first idea was to create something close to the Spectrum, a choice which Madge said meant "going down the same path as Oric" and which meant that by the time the Elan came out it would already be dated.

"Learn the lessons of other people's mistakes"

After that idea was scrapped, the team re-thought the concept from scratch, based on the idea of "if we could have everything, what would we have?".

This approach would clearly be too expensive, given the competetiveness of the market, but Madge still thought that there was:

"A technological window for a product which answered most people's complaints about existing home computers at a reasonable price"

He continued:

"We had reverse-engineered many machines so we could learn the lessons of other people's successes or mistakes. The Apple had a few too few keys and we had seen the advantage of products like the Atari which gave a wide colour choice. We are a programming house so we wanted a nice machine to program with[4]"

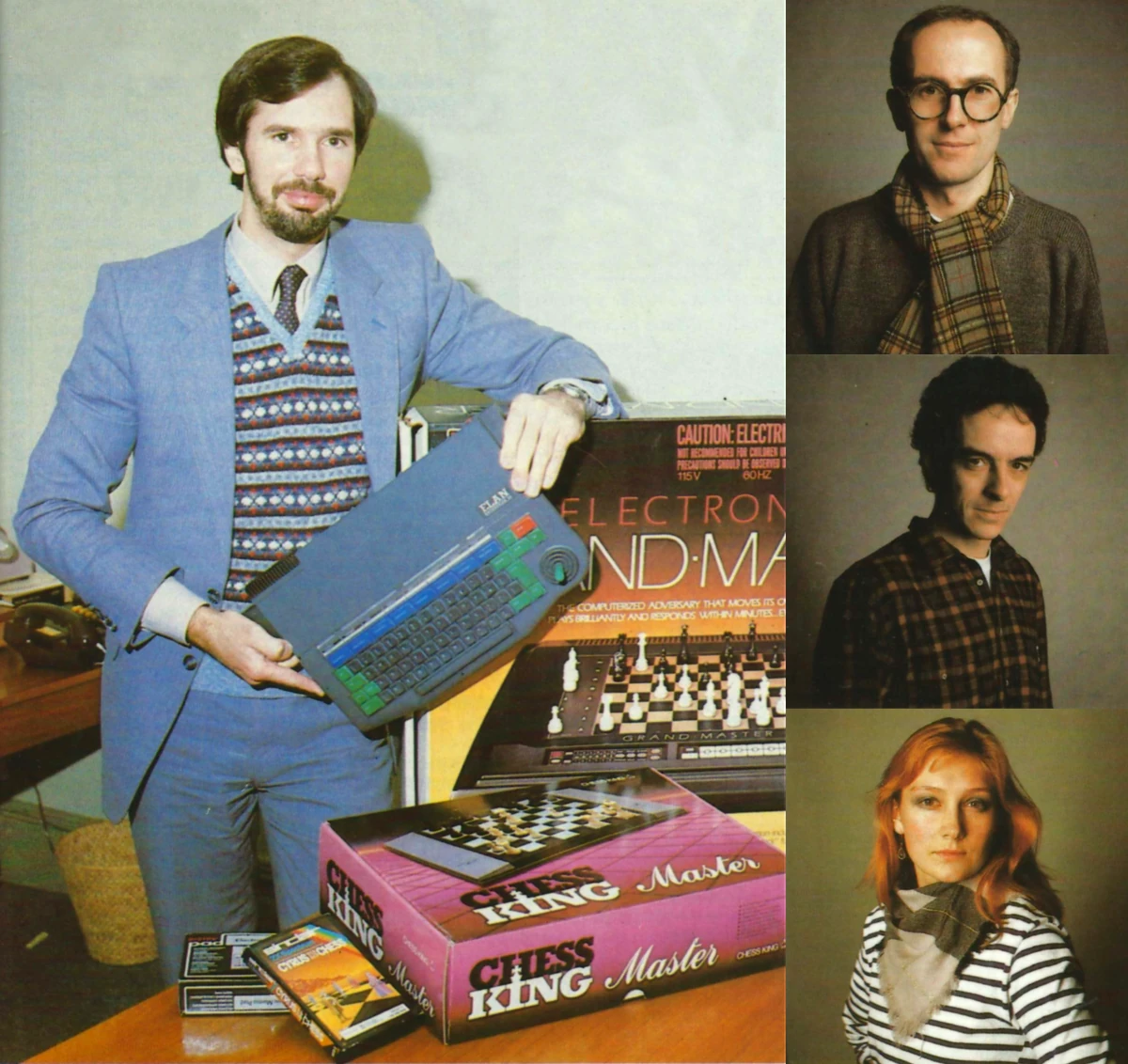

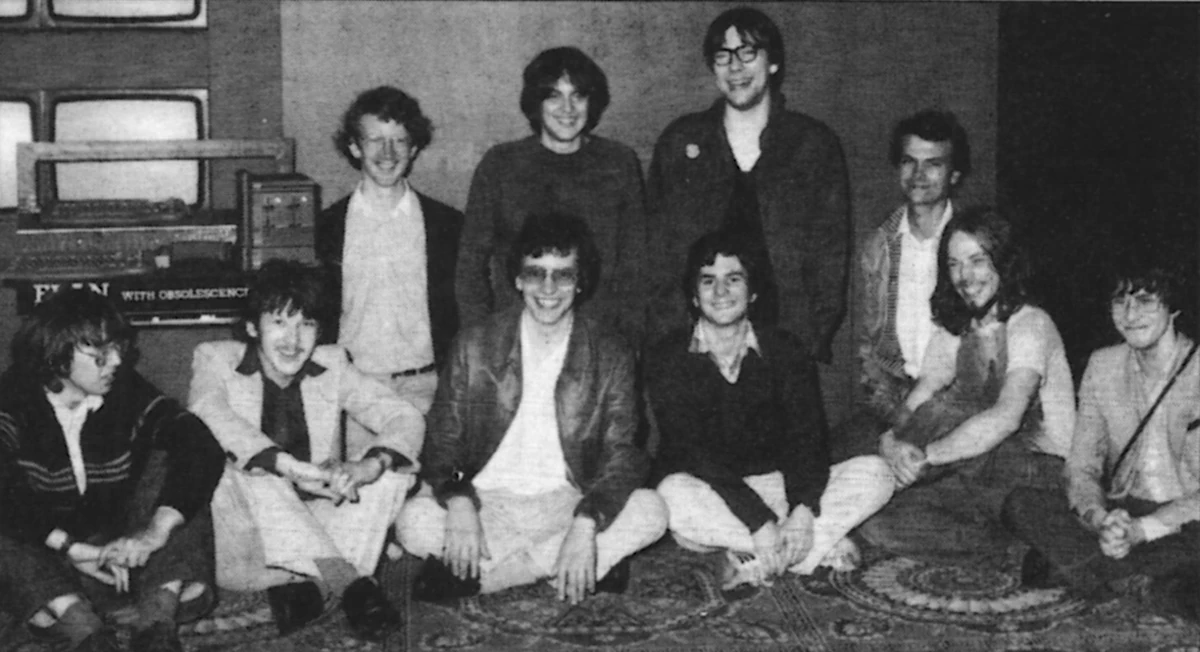

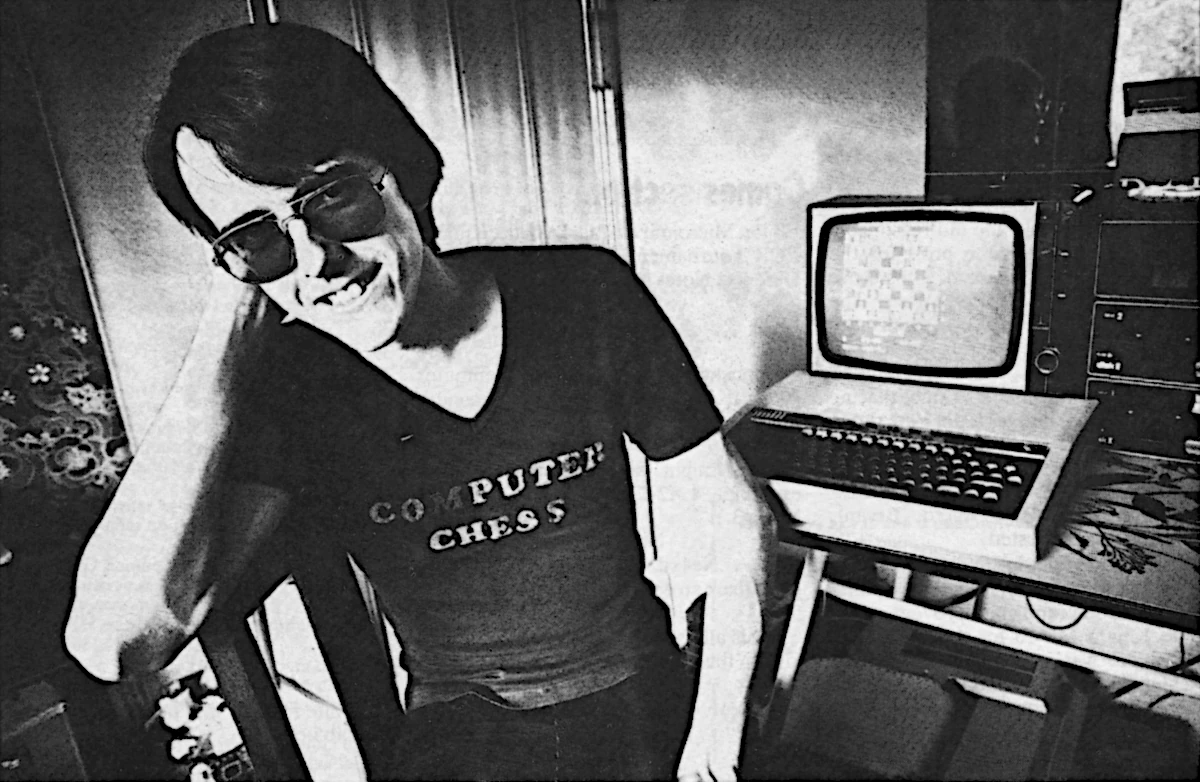

Some of the Intelligent Software/Elan team. Clockwise from the left: Robert Madge, holding a finished Elan whilst surrounded by some of IS's existing chess games and hardware; Geoff Hollington; Nick Oakley; Beverley Hobson, a member of Hollington's team

It was Madge, however, who steered the project towards a more conventional Z80A-based machine with 32K of BASIC ROM and up to 3.9M of RAM, as this - along with the machine's 80-column display - would leave open the option to offer CP/M and turn the Elan into a business machine.

Damp-proof course

By October 1982, the secret project had acquired a code-name of DPC, for Damp-Proof Course - in case the designs were "dropped on the bus". The outline for the new machine was then given to three sets of designers, which included Geoff Hollington and Nick Oakley, who said that they could come up with a design in only seven days.

The pair, having never previously designed a computer, worked all hours to come up with something different from the conventional home computer of the time, which Hollington referred to as a "currant bun" because they were just:

"printed circuit boards sandwiched between two sheets of cream plastic, with a few keys sticking out of the top"

After they returned to IS to show their sketches, the work they had put in paid off as they were hired immediately, even though, as Hollington said in an interview with Your Computer in January 1984, they were so tired that "neither of [them were] capable of coherent conversation".

"Obsolescence built out"

The final design for the Elan, along with the Hollington and Oakley keyboard and case design, had a custom graphics chip designed by Nick Toop.

Toop had previously studied at Cambridge University, written about and then worked for Sinclair[5] - or Science of Cambridge as it was then known - and then moved over to Acorn to help develop the Atom[6], a machine based upon the earlier Acorn System 1.

Toop's chip design meant that the Elan had an unusually-complicated set of 16 graphics modes, which could be mixed together on the same screen. Robert Madge said of this set-up that "I think everyone is going to be a bit bowled over by the speed of the machine's plotting".

The Elan's custom chip set was rounded out by a sound chip known as "Dave", developed by Dave Woodfield[7], which provided eight octaves of four-voice stereo sound[8].

With a company slogan of "obsolescence built out", the machine was also designed to be easily expandable via its 64-pin expansion port.

The original idea of having peripherals connect side-by-side from the edge of the Elan was quickly rejected as by the time the expansion box and a disk drive had been added, "you were off the end of the table". Instead, Hollington opted for a stacked hi-fi-style solution, with the expansion box and its up-to 4MB of RAM acting as the base unit.

This can be seen in the main advert, which shows the base unit with a twin floppy disk unit stacked on top of it, and possibly a modem on top with a question mark on it.

A new generation of home computers

By February 1983, the shape of the case had been finalised and a wooden mock-up had been commissioned, painted in two-tone grey which apparently "symbolised the difference between the heavy processing power of the micro and the friendly interface with the user".

This colour scheme was eventually dropped as a graphic design consultant bought in to advise on keyboard colours suggested that it looked "too specialist" for the home-computer market.

The finalised Elan, along with its original two-tone grey prototype, below. From Your Computer, January 1984

Once finalised, the final drawings were sent to a modelmaker who created the "form" from solid blocks of graphite. The form was then used by toolmakers to build the various case components, with seven different firms producing the parts.

Nick Oakley ended up commuting between these various companies and "living in a car" in order to ensure that the parts all fitted, but was expecting disaster at any moment.

Disaster duly arrived when it was discovered that the base component was about 5mm too long, and it was too late to get the mould remade. Luckily, it was easy enough to shave out a section, with the only sign in the finished product that anything had gone wrong being a ridge on the base that was slightly wider than the others.

IS/Enterprise starting teasing the upcoming release of its new machine in the summer of 1983.

Following its announcement as the first of "a new generation of home computers", the company - which by now had around 50 people working for it - remained tight-lipped about details, with Enterprise co-founder Kevin O'Connell saying:

"I have absolutely nothing to say. No information will be released until we are 100% ready. I'm afraid I'm going to continue to stonewall you"[9].

The Elan was officially launched in September 1983. However just three days before the event the rubber mat cushioning the plastic keys of the keyboard was still not ready.

Hollington and Oakley - designers of the keyboard - then spent the following 72 hours cutting out rubber membranes from old intercoms and glueing them into the demonstration machines so that the company actually had something to show.

Luckily for the company, the rest of the launch went smoothly.

"It is a weakness of the Japanese and Hong Kong companies"

About a month later, against the backdrop of a worsening home-computer market, what with the recent failures of Atari, Texas Instruments and Mattel, Enterprise still had nothing tangible to sell.

Robert Madge was still confident about the new machine and believed that it offered the best features from every home micro then available, rolled in to one. He explained:

"What we were asked to do in our brief was to design a computer which would be among the top few sellers, which would appeal on a whole number of levels - for games, for home business, for enthusiasts and novices and also appeal to commercial software houses who will have to produce material for it".

Unlike some competitors which were churning out me-too boxes - Madge offered the examples of Mattel, Sharp and Dragon - the Elan had been designed from scratch as an entirely new computer, an approach which Madge admitted "[had] considerable advantages and some disadvantages".

However, the approach did give Elan/Enterprise a potential competitive edge, as these generic machines often bought in all their system software from companies like Microsoft.

This choice left little scope in the way of customisation, as Microsoft had no interest in modifying or adding features to its well-established BASIC. Madge concluded:

"Most computer manufacturers do not have the experience to design a computer from scratch - particularly the software. It is a weakness of the Japanese and Hong Kong companies."[10].

An identity crisis: what's in a name?

Enterprise's wilfully detail-free emergency first advert, which was placed in an attempt to establish the Samurai trademark. Unfortunately, Nissei Sangyo had already shipped a micro with the same name. From Your Computer, April 1983

The name of the machine proved somewhat problematic.

Initially known as the Samurai, the name had to be changed after a brief legal tussle with Hitachi subsidiary Nissei Sangyo, as it had already released a machine of the same name, as distributed in the UK by Micro Networks[11].

That was despite Enterprise having gone through "all the correct procedures - registering a trademark and so on", and even - in an act of desperation - placing an advert in April 1983's Your Computer stating that "the Samurai home computer is coming".

Guy Kewney, writing in May 1983's Personal Computer World spotted the clash of names and adverts with Hitachi's Samurai warrior and Enterprise's cryptic advert and declared:

"No, they are not the same machine. No, they are not the same company. No, the deal has not been worked out between the two companies in advance. Yes, it is a terrible shame one can't buy shares in the solicitors' firms involved isn't it?[12]".

A second pre-launch advert for the now-known-as Elan, as seen in Personal Computer News, 23rd June 1983. Hoxton Street was part of the uber-trendy "Tech City and Silicon Roundabout" scene in East London

Then it was to be called Oscar and then Elan, which remained long enough for the company to do a re-launch with the cryptic "A new Elan will be launched on Sept 14th".

That name didn't hang around long either, with the company briefly renaming its computer as the Flan. Personal Computer News had asked Elan's marketing director Michael Shirley about this particular name change, to which Shirley replied:

"Yes. We have signed exclusive distributor deals in 20 countries now and found out that we could not use the Elan name in some of them".

"Some of them" apparently included the UK itself, where Enterprise/Elan had got in trouble with Elan Digital Systems of Crawley, Surrey over the name[13], only six weeks before the Elan was meant to have gone on sale.

Shirley continued "We decided to change the name so that the machine would have the same name throughout the world". When quizzed as to what the new name was, he followed up with "I can tell you that from now on the company will be known as Flan Computers", no doubt said with an especially stern face in order to suppress any potential laughter.

"People have been calling it the Flan computer anyway"

The reason for this was given that "well, some magazines have already started to refer to the micro as the Flan Enterprise", which was thought to be a reference to a typo that appeared in Personal Computer World[14].

Shirley had also said in Popular Computing Weekly that:

"The change from Elan to Flan was the easiest for us to do - some people have been calling it the Flan computer anyway"[15].

Coincidentally, Personal Computer World's former Programs Editor, Maggie Burton, was now working as Enterprise/Elan's software manager and was seen manning the Elan stand at 1984's Winter CES in Las Vegas, whilst David Levy and Kevin O'Connel were roaming around scoping out potential distributors.

Enterprise had spent £50,000 (£211,200) on going to CES but a working US version couldn't be produced in time so the company had a deserted stand with nothing to show.[16].

Only a few weeks after the change to Flan, the company announced it was set to change yet again, with Mike Shirley admitting that:

"We want to come up with a really good name that goes well with the company, and 'Flan' obviously isn't very suitable"[17].

Eventually, the company settled on the name "Enterprise", with the eponymous machine being officially launched in September 1983. At the time, Personal Computer News stated that:

"Elan Computers has launched its £200 wonder micro in the best British tradition. The machine beats all home computers (and many business machines) on paper but won't be available until April. As a micro, its spec is miles ahead of contemporary systems, but then so is its delivery date"[18].

Elan's ANSI BASIC

Even the machine's BASIC, which was being written to ANSI standards and which had lots of additions to support large and structured programs, had been in development for over a year and was not yet ready.

The reason for a bespoke version of the popular programming language went back to Enterprise's wish to not be constrained or limited by taking an off-the-shelf version of something like Microsoft's standard BASIC, which most home computers at the time were using a variant of. As Robert Madge explained:

"We had to have BASIC in a very good and enhanced form, with particularly strong graphics and sound - these are the starting point for all independent companies to produce software for it. We [also] had to make sure that, with the BASIC and operating-system software, we hadn't closed the door on any future development. We are not crystal ball gazers. Who knows what we may wish to be connected to a computer in the future?".

The team of Intelligent Software programmers who worked on the Elan. From Your Computer, January 1984

As such, Enterprise became the first company to implement its own version of BASIC, from scratch, to the ANSI standard which had only recently proposed by the American National Standards Institute. Madge said:

"We wanted a BASIC which was likely to be accepted as the standard programming language of the future - a version which would answer most of the objections people make to Basic. In the Elan, I think we have achieved that"[19].

Slow progress

When the Elan/Flan did become available in significant numbers in early 1985, around 18 months late (although some early-production machines for sale and review had appeared at the end of 1984), it was up against machines like Sinclair's QL and Amstrad's new competitively-priced CPC 464.

The delay in launching was partly down to the constant name-changing but was also because debugging the two custom chips was taking longer than expected. Marketing manager Shirley commented:

"[it] is going painstakingly, but well. We would rather bring out a reliable product in September than an unreliable one earlier".

In anticipation of an eventual launch, Enterprise/Elan signed a deal with Welwyn Electronics in March 1984 to produce both machines, including the 128K model which wasn't expected to appear until the beginning of 1985.

The deal was expected to create 90 jobs at Welwyn's Tyneside factory, however it appears to have fallen through as by the end of 1984 Popular Computing Weekly was suggesting that the Enterprise was being manufacturered in Perth, Scotland, by GRI Electronics[20].

Meanwhile, Popular Computing Weekly announced the winner of its "Find a name for Flan" competition, with Bernard Dinneen's winner being "Teflon Computers - because they can't find a name that will stick"[21].

When the first batch of Enterprises finally arrived in shops during Christmas 1984, they were quickly scooped up, with all machines delivered being sold.

A spokesman for John Menzies, the Scotland-based newsagents chain said of their trial of the Enterprise that:

"We're pleased with the initial interest shown, however we have to see what customer response is in the long term before we can make any sort of commitment".

WH Smith was also testing out the market for the Enterprise and reported that it would decide at a later date whether to add the machine to its range. Caroline Jones of Enterprise said:

"From the feedback we've had the Enterprise sold out within days of it appearing in a limited number of shops"[22].

Intelligent Software recruitment advert, © Personal Computer World, September 1983After the initial flurry of excitement, sales were slow, partly because the machine was no longer as groundbreaking as it would have been had it been launched on time in 1983 and it was £50 more than its previously-promised magic price tag of £200, but also because the competition hadn't exactly been standing still either.

There was also the problem that a very limited amount of software was available at the time of launch, with only four software packs written entirely in BASIC being available.

Enterprise's Mike Shirley seemed to conceded that this was not ideal, saying "obviously we will be doing a wide range of machine-code games later, but at least we're getting some out".

Shirley also suggested that the fact that the games were written in BASIC was actually a bonus as it enabled the user to "break into the program[s] to see how they work"[23].

Despite the significant lack of launch software, it was hoped that the launch of 14 new software titles in Spring 1985 would help, with negotiations under way for more titles with some of the big software houses, such as US Gold, Firebird and Ocean.

Enterprise hoped to have a 100-title range by the following Christmas, and there was even to be a game based on the latest James Bond - A View to a Kill. The game of the film, designed by Speshal K and released by Domark, was the first time that Bond had ever - at least officially - been the star of a computer game[24].

Intelligent Software itself was also due to release twelve programs under the "Enterprise" label in the February of 1985, including, not surprisingly a chess game, as well as an assembler/disassembler, programming languages Lisp and Fourth and various games.

Production of the Elan/Flan/Enterprise at this point was running at a rate of "several thousand a month", although Shirley admitted that the company was not yet up to full-scale production, saying:

"We've made substantial progress in a difficult time of year. Against the market background we've done extremely well"[25].

A month before, Shirley had also claimed that Enterprise was coming out with "eight titles a month" and that the company was aiming to grab 10% of the market - or more than 150,000 machines - by the end of 1985[26].

Price cuts

When the 128K model was finally launched in the week of 23rd May 1985[27], the price of the original 64K model was dropped to only £180 (£720 in 2026).

Sales of the 64K machine had so far been "just under 10,000" with the company optimistically predicting combined sales of 150,000 by Christmas with an additional 200,000 being sold abroad. Enterprise's Shirley said:

"I don't believe there is anything around to challenge us on quality and price - it's going to be a 128K Christmas. It significantly out-performs machines such as the BBC B Plus and the QL at almost half the price"[28].

It might have been almost half the cost of the BBC, but that still put it in the high end of the market, with Popular Computing Weekly suggesting that it was "too high [a price] to cause much of a stir".

The price drop of the 64K machine was welcomed though, or as John Cochrane wrote in his review of the Enterprise 128:

"perhaps the best thing about the launch is the price reduction on the existing 64K model. For £180 the Enterprise 64 offers better sound, display and programming capabilities than almost any other computer in a similar price range".

Cochrane continued however with a somewhat damning:

"Both Enterprise models suffer from a lack of software at present and until such becomes available, it is difficult to justify the cost of the 128K model"[29].

Despite the price cut, the predicted massive surge in sales didn't happen and it didn't help much that by September 1985 there were all-out price wars in the 128K market.

Commodore had dropped the price of its CBM 128 to £269 (£1,080) - not forgetting that the 128 had the huge advantage of having C64 compatibility, which meant there were in excess of 6,000 software titles available for it[30].

Meanwhile, Amstrad had also just released its new CPC 6128 "battering ram"[31], which retailed for only £300 (£1,200), only £31 more than the Commodore, but that was for a package which actually included a disk drive and monitor[32].

The 8th Personal Computer World Show at Olympia in 1985, with the Enterprise stand towards the front. From Personal Computer World, August 1986

By the time the Personal Computer World Show rolled around in September, the 64K Enterprise was nowhere in sight. An Enterprise representative on the stand told Popular Computing Weekly that "Frankly, the 64K machine simply isn't in demand".

On the upside, Enterprise was showing off its ExDOS disc controller, which gave the Enterprise 128 access to any floppy disk drive that implemented the Shughart 410 interface, be it 3", 3.5" or 5.25", even in MS-DOS formats[33].

The end of the line

By the end of 1985, Enterprise was looking into the idea of bundles or more price changes to its 64K and 128K machines, as it admitted that there had been problems getting its machines into shops.

These problems were exacerbated when shipments were halted by distributors Terry Blood Distribution. Mike Shirley summed up Enterprise's dilemma when he suggested that:

"it's an interim thing. TBD had difficulties distributing the product because we were not going into the major multiple stores. The independent retailers also found it difficult to market a product that was not stocked in the High Street".

Shirley continued "We have proposals for the New Year", which was a nod towards a meeting for fresh discussions with TBD at the beginning of 1986, and:

"[there is] new hardware we are working on. 1985 has been a difficult year. The High Street is selling more and more of the hardware, and we must devise a strategy to get into those multiples"[34].

Despite the problems, the Enterprise still got some good, if reserved, reviews, including Personal Computer News' verdict which said:

"A year ago the Enterprise would have stood out as a market leader. Today, with Sinclair, Acorn and Commodore and perhaps MSX all becoming household names, it will probably have a much harder time making an impact. Even so, it's not a bad machine. The Basic, for all its length, is extremely good and should prove easy to use, especially for the beginner"[35].

Enterprise's technical support head Steve Groves defended the machine against some of its critics, including that of Andrew Pennell's otherwise-largely-positive review in Popular Computing Weekly, when he wrote:

"We were sorry to see that Andrew disliked the Enterprise keyboard. Opinions vary - it's largely a matter of personal preference. To date we've found users' comments encouraging - perhaps he will find that familiarity will improve his opinion".

Groves was also keen to reinforce that the company was taking software seriously, stating:

"The success of any home computer manufacturer is dependent upon the software available. The Enterprise offers tremendous opportunities to programmers and software houses have been quick to realise this. We are currently working with several major software houses to produce new programs and convert existing ones"[36].

It was not to be though, and by the summer of 1986, Enterprise had racked up debts of around £8 million[37]. It was liquidated shortly afterwards.

Just before its collapse, Enterprise had been working on prototype for a follow-up to the Enterprises 64 and 128.

Called the Vulcan, it was to have been both CP/M compatible and backwards-compatible with the two previous Enterprise micros.

With 320K RAM as standard and running the Z8000 processor, the £400 machine would also come with a 3.5" floppy and a monitor, as well as a bundle of software including Supercalc[38]. It never saw the light of day.

However nine months after Enterprise folded, it looked like it might return from the dead.

After it collapsed, its assets had been bought by Indian company Broadlight, before it was sold on to a German company, with which former Enterprise executive Neil Blaber was in talks to act as the UK agent to sell software, peripherals, and actual Enterprise computers.

Blaber was quick to point out that "Enterprise is not officially moving back to the UK yet, but it might be", before going on to suggest that the price of the machines on their return to the UK would be "competitive", at around £60 for the 64K model[39].

--

The marvellous, mechanical, Micromouse

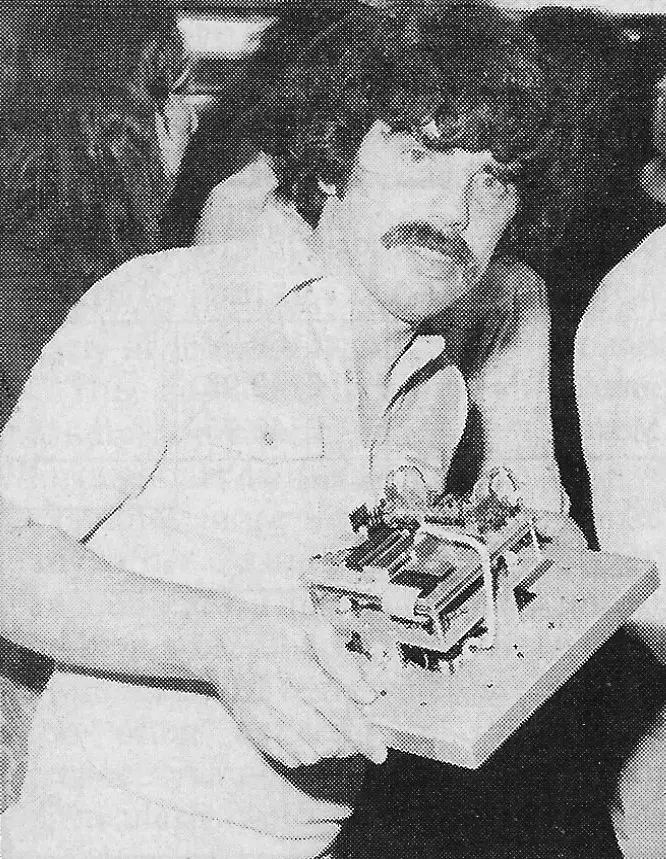

Dave Woodfield, with his 'mouse' Thumper © Practical Computing May 1982Enterprise's Dave Woodfield was already vaguely famous as the winner of the second UK "mouse" competition, from the days when "mouse" meant something entirely different.

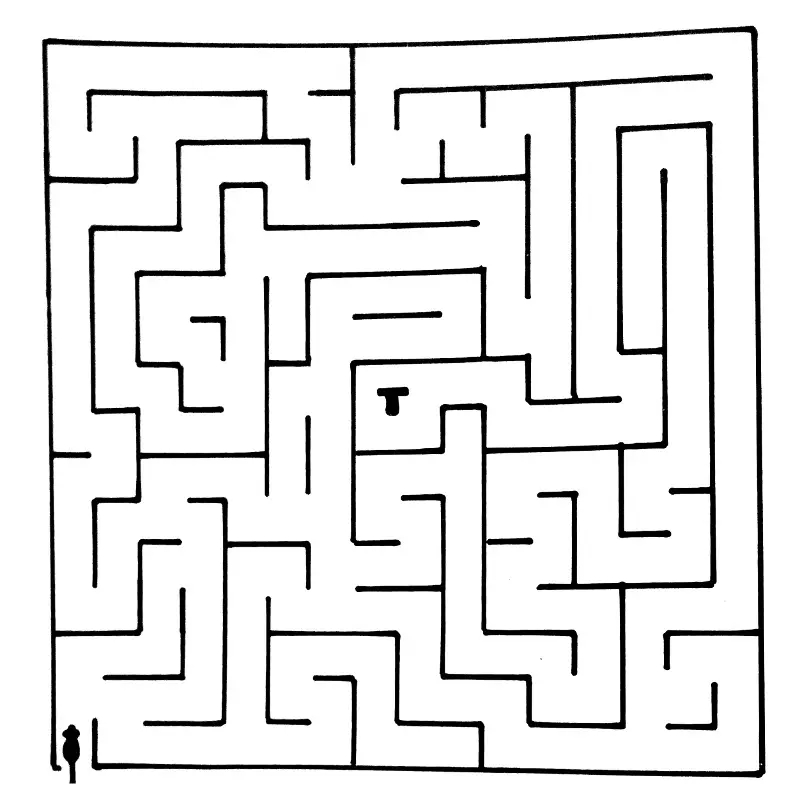

Set up in 1980 by John Billingsley of Portsmouth Polytechnic from a modified version of a competition first held in New York in 1979[40], the Micromouse contest challenged small robotic vehicles - similar to Turtles - to find their way unaided to the centre of a maze.

Woodfield's entry - Thumper - had won the 1981 contest, which was held in Wembley, with a time of 45 seconds, easily beating the next-best time of one minute 15 seconds.

That was despite Thumper "banging his head against the wall faster than you can say 'heavy metal'", according to Practical Computing.

The competition also included a mouse called Thezeus, built by Alan Dibley and which was driven by a ZX80 with its membrane keyboard sawn off so that Dibley could attach sensors in lieu of keys[41].

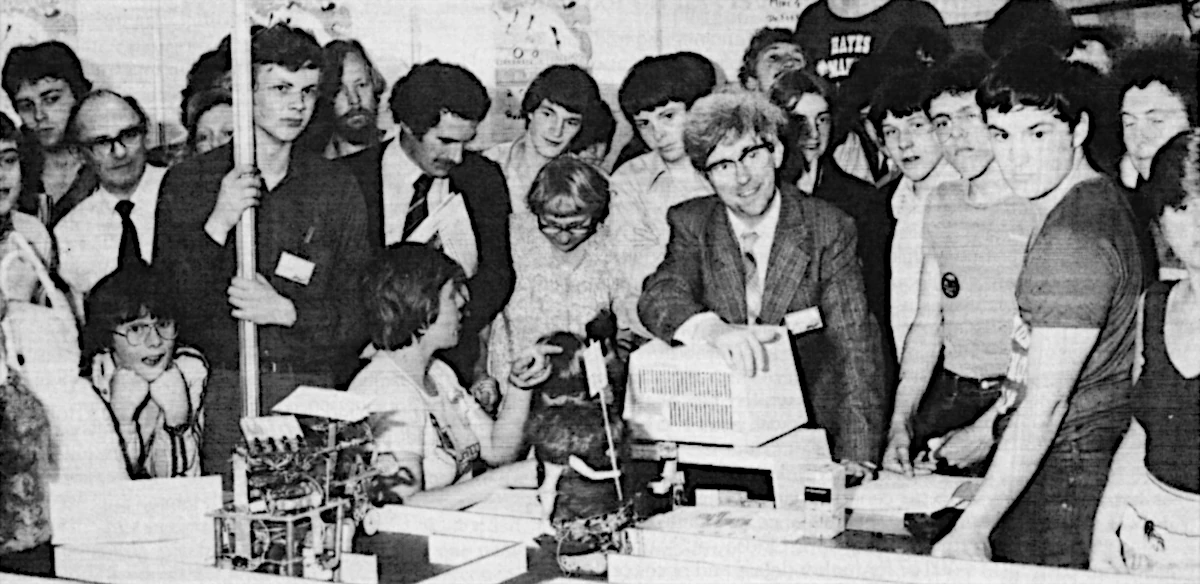

The second UK Micromouse contest, weld at Wembley in 1981. From Practical Computing, October 1981

Also featuring was Nick Smith's Sterling Mouse, which had won the very first UK contest as well as a competition heat at the Micro Expo Exhibition in Paris in 1980.

A variant of Thezeus, called Yetanotherthezeus or T3, won in 1982 at Earls Court, with Thumper nowhere to be seen[42], however Woodfield was around for the finals of the '82 Euromouse contest on September 25th, held in Tampere, Finland.

The Tampere mouse maze for the September 1982 competition, said to have been the hardest yet seen. © Practical Computing, December 1982Competition was fierce, with the local Tampere mouse setting a practice time of 40 seconds, however the sand which had been added to the maze's surface in order to add grip was proving to be challenging.

Alan Dibley was two mice down thanks to his check-in bags being thrown in to the aircraft hold upside-down on the way over to Finland, whilst Woodfield's Thumper was back, but with a slightly pedestrian time of over six minutes.

Dibley's Thezeus 4, meanwhile, managed a clean run of 45 seconds, which the Finns couldn't beat, and he claimed the prize of a pine-mounted mouse trap and some cash donated by Tampere Technical University.

Woodfield also popped up again when he was ranked seventh in the 1985 contest with an entry called, appropriately, Enterprise.

The Spectrum lives!

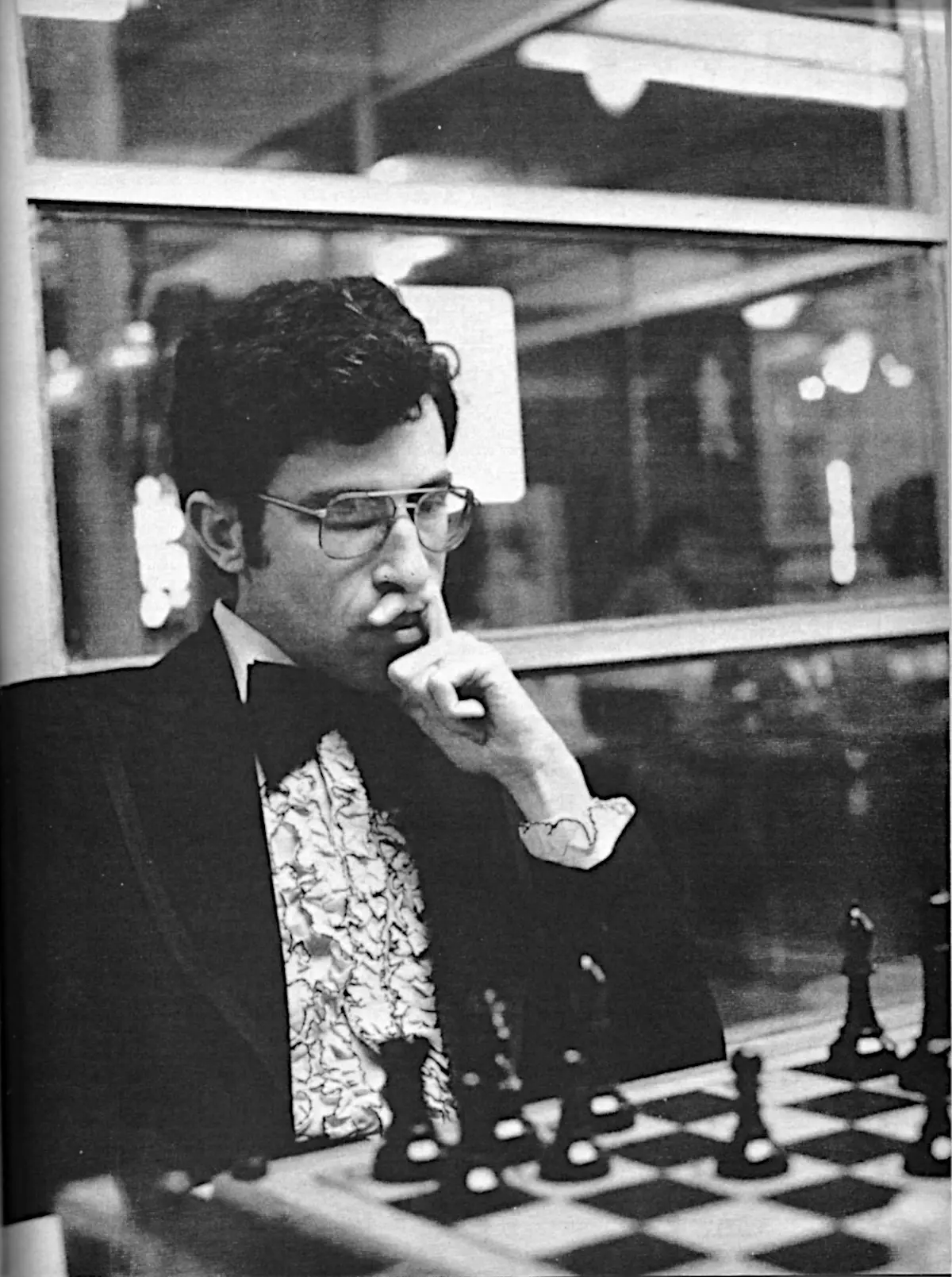

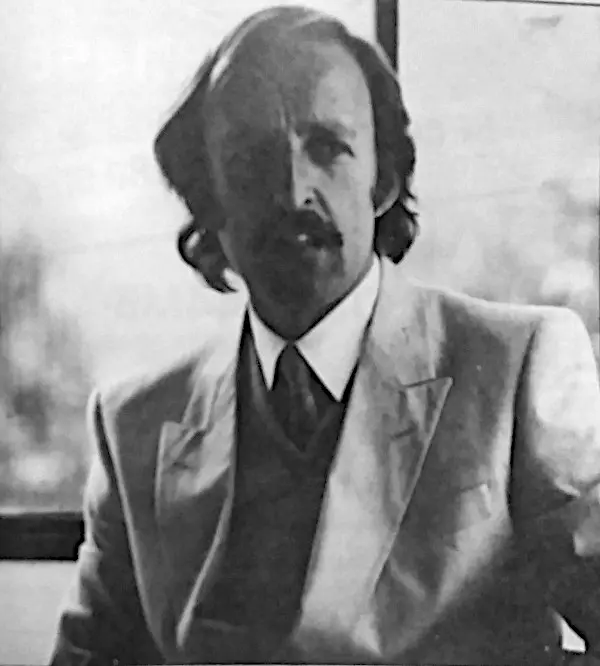

David Levy, © Popular Computing Weekly August 1983David Levy continued to write books on games, AI and robotics, accumulating 50 titles to his name, as well as founding Computer Olympiads and becoming president of the International Computer Games Association.

He became chairman of Beeston, Nottinghamshire-based Retro Computers, a company which counted Clive Sinclair among its investors.

Retro launched the Sinclair Spectrum Vega in 2015[43], a new crowd-fund-developed version of the Speccy - the very machine that precipitated the development of the ill-fated Elan - but with 1,000 games built in to its ROM and no Microdrives in sight.

Although it had no keyboard, there was a nod towards the original Spectrum design with the inclusion of five Spectrum-style rubber controller keys.

David Levy said of the rationale behind the machine that:

"because we are providing 1,000 games in the Vega we expect that our product launch will also be extremely popular with many computer games enthusiasts who have not yet experienced the joys of the Spectrum, but at a tiny fraction of the cost of building such a vast games collection in the 1980s. We therefore believe that the Spectrum community will grow and grow as more and more games enthusiasts acquire a Vega."[44].

The average cost of cassette-based computer game in the mid-80s was around £5, so such a collection would have cost a not-insignificant £21,100 in 2026 money to acquire.

The much-delayed follow-up, the Vega+, became mired in controversy[45], and the company was wound up at the beginning of 2019, having burned through over £500,000 of crowd-funded capital with nothing to show for it[46].

Madge's Token Ring

Robert Madge, meanwhile, went on to found Madge Networks, a company which went up against IBM in the nascent networking market of the late mid 1980s, with its version of a token-ring network - the briefly-dominant networking standard that came out of the development of Maurice Wilkes' Cambridge Ring network, which had also involved Andy Hopper of BBC Micro fame[47].

Madge's company even managed to score a significant win over Big Blue when it released the first Micro-Channel Architecture network cards for IBM's PS/2 machines, with Microsoft even picking up support for the cards and the software they required.

The drivers for the network cards were written in cooperation with giant US network company 3Com, with Madge's company supplying the hardware.

Madge was downplaying the significance of his company's win against IBM, suggesting that the advantage over IBM was not that important. "We'll ship from June, IBM will ship just before the end of the year".

Guy Kewney, writing in Newsprint, reckoned that this attitude was more down to modesty than sense, and was a reflection of how well Madge Networks was doing at the time[48].

The rise of the (chess) machines: a brief history of David Levy and computer chess

When it was first approached, Intelligent Software was not long-established, having been created in the Autumn of 1981 by David Levy and Kevin O'Connell.

The pair had both started out as professional chess players and writers in the early 1970s, before joining up to form Philidor Press in 1975 when they both realised they were writing most of the chess literature of the day.

Both Levy and O'Connell frequently contributed to Personal Computer World, with Levy in particular writing a whole series for the magazine on game theory.

Some of David Levy's Computer Chess books, from a Bits Inc. advert, Byte, December 1978

A year later, after the international chess tournament in Dundee, Levy apparently took a £500 bet at a party in Edinburgh that no computer program would be devised before 1986 that could beat a grand master - a wager, it has to be said, that was slightly less than the $100,000 that had been offered by the Fredkin Foundation of Cambridge, Massachussetts in 1980 for the first program to win the World Chess Championship[49].

This differs from the version of events published in Popular Computing Weekly in April 1984, where Levy was said to have placed a $5,000 bet in 1968 that no computer could beat him at chess within ten years - a wager which was extended in 1978 for another ten years, as at the time Levy had successfully fought off all challengers.

Levy even promoted the bet the following year in a detailed article, published in May 1979's Personal Computer World, about how to actually write a chess program for a computer, where he referred to it as the "$5,000 Levy/OMNI prize"[50].

Claude Shannon - left of centre, and known as the father of computer chess - makes a guest appearance at the Third World Computer Chess Championship held during the Ars Electronica Festival in 1980. David Levy is on the left. Credit: LIVA–Linzer Veranstaltungsgesellschaft mbH, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

David Levy was born in 1946 and was three years old when the first paper to describe how a chess-playing computer program might be devised was first presented by computer-science pioneer Claude Shannon at the National IRE Convention in New York in 1949.

The ground-breaking paper was published the following year in the Philosophical Magazine[51].

By the time Levy was ten, the first game against a human player had been won by a computer when Maniac - developed at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory - beat a novice player in 23 moves.

By the age of 22, Levy was "expert rated" and was the Scottish National Champion. It was this year - 1968 - when Levy was attending the Fourth Annual Machine Intelligence workshop that the debate about when a machine would beat a human first ignited.

Levy had taken exception to John McCarthy of Stanford University and Professor Donald Michie of Edinburgh University, who both argued that a computer system would be World Champion within ten years.

Levy didn't agree, and claimed that no computer would be able to beat him in a tournament-style competition during that ten year period. Neither was able to convince the other, and so the famous bet came to pass, although in this accounting of events - in December 1978's Byte - the amount was £1,250 - about £28,400 in 2026.

During the early 1970s, the first inklings that chess computers were getting serious came when Northwestern University's Chess 4.0 achieved a US Chess Federation rating higher than that of the average tournament chess player.

Then in 1976, and the following year, Chess 4.5 and 4.6 won the Class B championship at the Paul Masson Open, and then won outright in Minnesota.

In late 1977 and early 1978, Levy played againt Chess 4.6, "Duchess" from Duke University, a system from MIT and Kaissa from the USSR, beating all of them in the first game.

However, Levy considered that his upcoming match with Chess 4.7 might not be a formality and would be "a bit of work".

David Levy plays on-line chess against a Control Data Corporation Cyber 176 computer, running Chess 4.7, at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. From Byte, December 1978

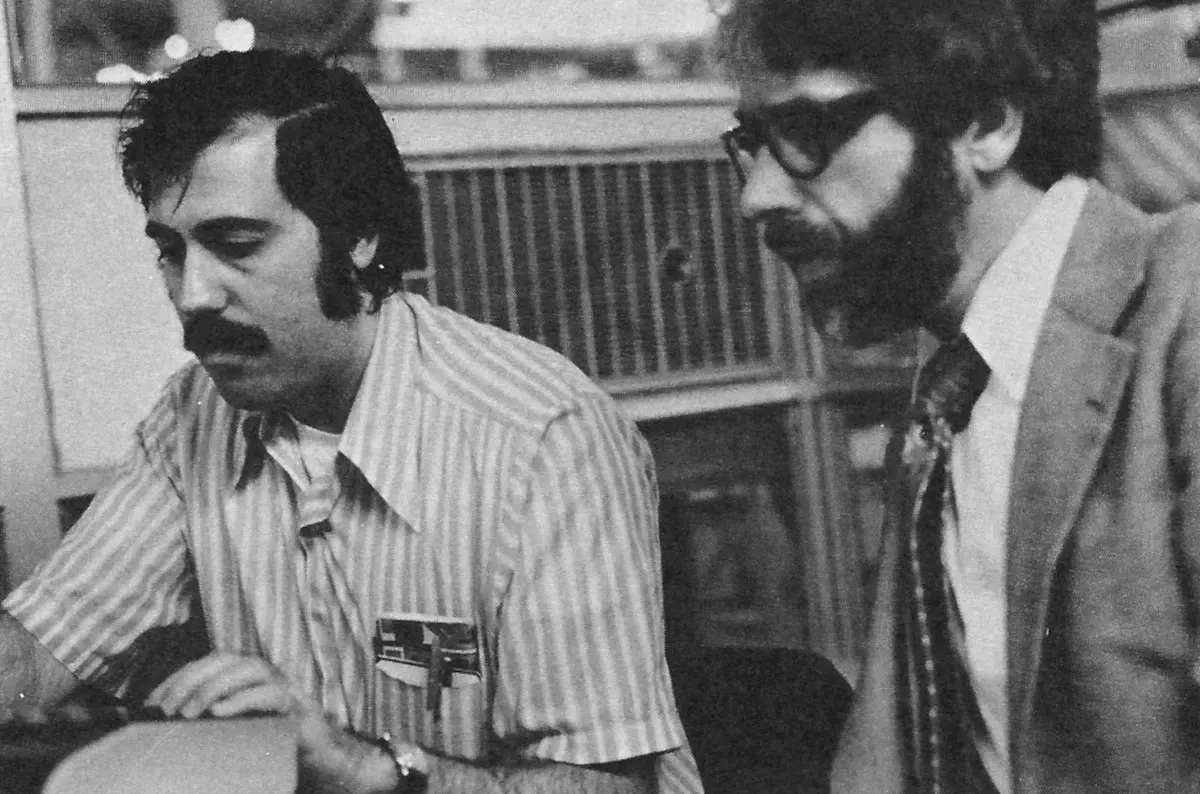

The match was scheduled for the tenth anniversary of the original bet - Saturday August 26th 1978 - and required some significant set-up as the tournament was in Toronto whilst the computer Levy was to play against - the Control Data Corporation (CDC) Cyber 176 - was located in Arden Hills, Minnesota.

It took most of a week to set up the telephone lines and modems between the two. As the match progressed, J. R. Douglas, writing in Byte, observed:

"The relationship between the opponents in the Levy match is difficult to describe. The two Davids - Levy and Slate [co-author of Chess 4.7] - and the CDC folks stayed in the same hotel and ate meals, travelled and generally spent the entire time together as friends. Levy even considered the machine to be a sort of friendly foe. Each night the entire group found itself on the sidewalks of Yonge Street playing chess on overturned milk cartons with Joe Smolij [local speed-chess champion and guru of the Yonge Street Chess Association] until the small hours of the morning, with Joe demonstrating his 'Smash-Crash' gambit for 50 cents a lesson"

David Slate, of Northwestern University, and David Cahlander of CDC, watch Game 4 on the computer terminal. From Byte, December 1978

Levy would eventually hold out against Chess 4.7, after a draw in the first game created much speculation since experts had predicted a straight three-game conclusion to the six-game match.

The match finished with a score of 3½ to 1½ in Levy's favour, which meant Levy won his ten-year wager, however there was a feeling after the match that "there were no losers in Toronto".

After the match, Levy kicked it all off again when he offered a prize of $5,000 - about £26,400 now - to any developer of a system which could beat him over the following five years[52].

So far, all these challengers were chess programs running on mainframes, but 1978 was also an important year for microcomputer chess, with the first ever competition for micros being held in San Jose, California, in the early March of that year[53].

The event, held during the second West Coast Computer Faire, was won by Dan and Kathe Spracklen's Sargon[54].

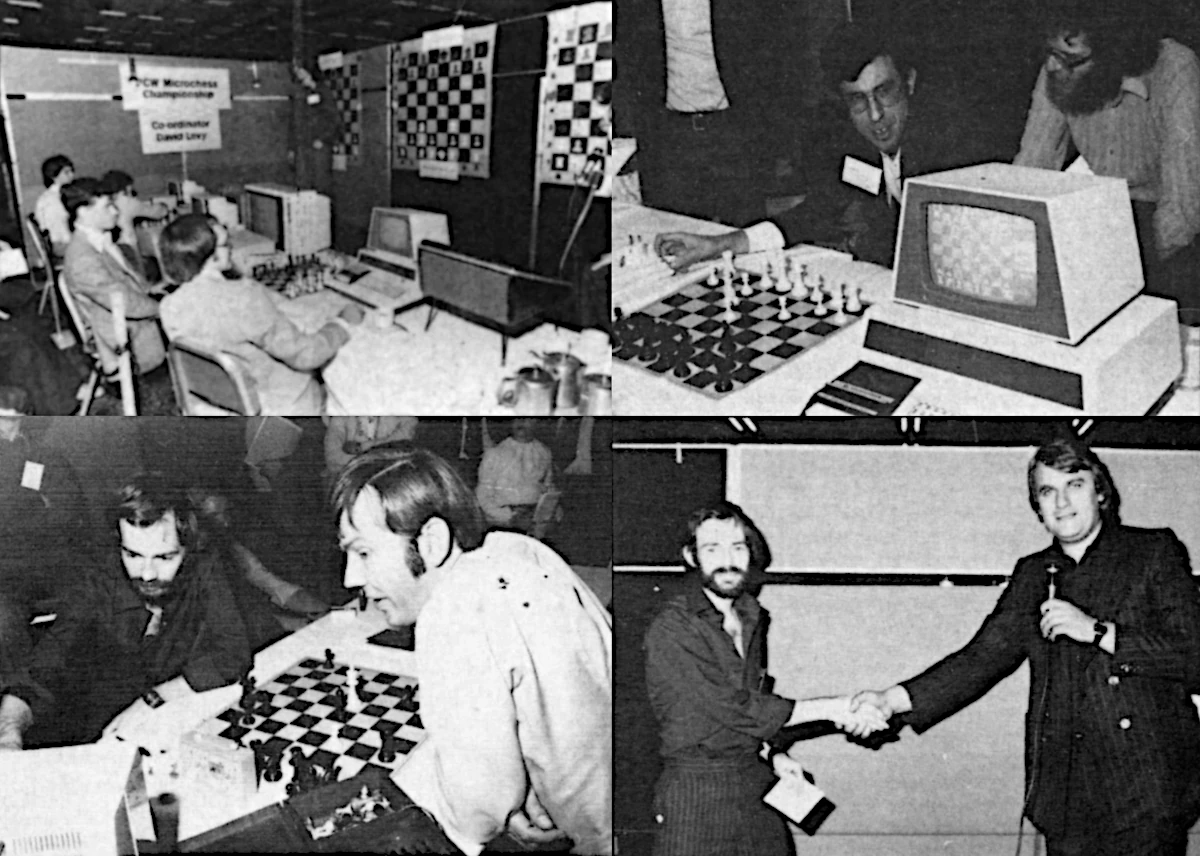

A few months later in September, Europe's first ever microcomputer chess championship was held as part of the Personal Computer World show at the West Centre Hotel in London.

Europe's first-ever microcomputer chess championship - the PCW Microchess Championship - held in September 1978. David Levy is on the left of the top-right-hand photo, which also shows Personal Software's Microchess 2.0 running on a Commodore PET 2001. On the bottom left, Mike Johnson's Mike plays Rex Kent with Boris, and Mike Johnson is presented with a cheque for £200 by (probably) Angelo Zgorolec of Personal Computer World in the bottom-right photo. From Personal Computer World, November 1978.

The match featured six entries - three from the UK and the rest from North America, which included Chess Challenger and Boris from the US.

Also present was Canada's Peter Jennings with MicroChess 2.0 - a version of the hugely-successfull franchise that was published by Personal Software, the company that would go on to launch the famous spreadsheet VisiCalc in the following year.

David Levy was tournament director of the event, and had not been especially optimistic about the standard of play he expected to see from the micros in the competition.

However, it seemed to exceed his expectations, as he wrote in a review of the competition in November 1978's Personal Computer World that:

"I must confess that I was pleasantly surprised when I discovered that the best programs were playing at about the level of the average mainframe program of a decade ago. Presumably, since micros are readily available to almost anyone with a yen for programming, many more chess programs will be written for home computers during the next few years. Within a decade there will be matchbox-sized machines that can play chess as well as the current World Computer Champion, Chess 4.7".

The competition was eventually won by Mike Johnson of the UK, running his chess program Mike on a home-built 6800-based micro. That was despite having to abandon the first game as the power-supply voltage kept dropping, causing the machine to fail. A hastily-fetched transformer kept the machine running, allowing Mike to win 4½ to 3½ after a tie-break[55]".

Cyrus IS Chess, also available for the Sinclair Spectrum. From Personal Computer World, August 1983

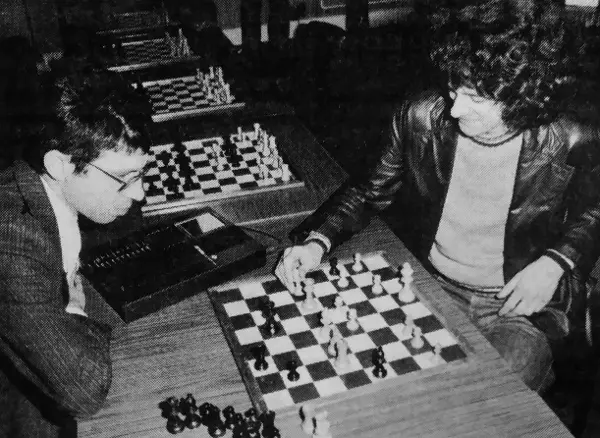

A couple of years later, at the 1981 PCW Microchess Championship, the first version of Cyrus - the chess program later published by Intelligent Software and written by Richard Lang - appeared and beat everything in sight, winning five out of five games.

Another entrant in that year's competition was Martin Bryant, who had first become interested in computer chess whilst at Manchester University.

After a failed attempt at writing a chess program from scratch, he had discovered a copy of the program which had won the 1971 ACM chess tournament on the university's Control Data Systems' Cyber 72. He said in an interview published in August 1983's Personal Computer World that:

"It took me a while to stumble on the program because it was hidden away in one of the systems programmer's storage files. But the programmer left a listing of it lying around and I found it. I thought it looked interesting and that I could pick up some tips from it. I also bought a book by Monro Newborn called Computer Chess. That taught me about minimax, scoring functions and all the other good things you need to know about to put a decent chess program together. I wrote White Knight Mk. 2, my second chess program, incorporating these things. It was a better program and it played legal chess - not very well but at least it was up and running".

A few version later, and White Knight Mk. 4 became the first version that beat Bryant, with even more seven-hour days of programming resulting in Mk. 5. This had become such a mess of extensions, so required a complete rewrite, leading to Mk. 6.

Eventually, with the end of his degree in sight and the loss of access to the Cyber 72, Bryant purchased an Apple II and learned 6502 Assembly Language programming.

Keen to enter the 1981 Personal Computer World competition, White Knight was translated from its native Pascal into assembler, a process which required leaving out large chunks of the algorithm in order to fit into the micro's more-limited memory.

It was this version - Mk. 9 - which was entered into the show, but it fared poorly coming 10th out of 12. Bryant said:

"I was a bit disappointed. As far as a mainframe program was concerned, White Knight was rather good and I expected it to be better than most micro programs even in its cut-down form".

However, the competition provided a lucky break: Bryant met Intelligent Software's Levy and O'Connell, who were looking for chess programmers, and they offered him a job. This started in October 1981, by which time Richard Lang was already working for the company. Bryant continued:

"Over that next year we pooled our knowledge. Our approaches to computer chess programming were very different but there were areas inside both our programmes where we could draw on one another's work. Lang developed Cyrus II while I went on to produce Mk. 10. This was designed specifically to fit on a micro ... in the end if fitted inside 36K, while the Mk. 9 had barely squeezed inside a 48K Apple".

Mk. 10 went on to do relatively well in the 1982 PCW championship, scoring 3½ out of 7 and winning a prize for the second-best amateur program. Even better for Bryant was that Meyer Solomon, once editor of Personal Computer World but now publications manager at the BBC, was also at the show and was looking for a chess program for the BBC Micro.

After a brief meeting and an expression of interest, further talks in October led to a contract and a new version for the BBC - benefitting from twice the processor speed as the Apple II - was released as Mk. 11 in 1983[56].

Martin Bryant and his development BBC Micro, running White Knight Mk. 11. From Personal Computer World, August 1983

Back in October 1980, Levy went on to release his own £295 chess-playing microcomputer, with software written by Mike Johnson - winner of the 1978 PCW competition - and circuits designed by Barry Savage[57].

Later, the pair went on to develop the SciSys Chess Champion Mk 3, which at one point was endorsed by Anatoly Karpov.

They followed this up with the Mark 5 Chess Champion which went on to win the 1981 commercial chess computer world championships held in Travemünde, West Germany, as well as the World Microcomputer Chess Championships in Hamburg.

Iain Sinclair, © Practical Computing January 1983The £279 (£1,330 in 2026) Mark 5 chess computer could play 12 games at once and was styled by none other than Iain Sinclair, brother of the legendary Clive[58].

Sinclair (Iain) had been commissioned by Sci-Sys to design its entire range of chess computers, which was a complex task involving the interface between the analogue world of traditional chess pieces with the digital-only microprocessor world.

In an interview with Practical Computing, Sinclair, who believed that good design - something which was often overlooked in the computer industry - was a fundamental ingredient of a successful project, suggested that "Futuristic design is essential for computer products" and that "People want to feel that they are living in the science-fiction future".

Nevertheless, he conceded that:

"Sometimes what is desirable from an aesthetic point of view is not achievable in practice, the limiting factor being either technological or simple economics".

The design-centric ethos was very much shared by brother Clive's adherence to the similar principals of "elegant design".

Sinclair - who insisted on being paid up front for his design work - went on to design for Acorn as well as its offshoot Torch, and it was here where he definitely came up against economics as a limiting factor, as only part of his design made it into the finished Torch Communicator.

He also designed the first digital clock as well as the superfluous turbo version of the Austin-Morris Metro[59].

Meanwhile, IS went on to create a self-moving chess game for Milton Bradley, a Bridge training program for Tandy's Color Computer and developed the La Regence chess program (derived from Lang's original Cyrus) with the backing of a Paris chess-set distributor Ries. La Regence even beat a Cray supercomputer at the ACM (Association for Computing Machinery) Blitz Tournament in 1981[60].

David Levy, left, looks on as Dr. Nunn considers the Zagorujko chess problemIn 1982, SciSys's Mark 5 featured in Silica Shop's first Chess Computer Symposium where it, along with two other chess computers which along with the Mark 5 were considered the strongest then available - the Champion Sensory Challenger and the Great Game Machine - were up against human opponents drawn from the South East.

Whilst the machines did well, the Symposium revealed that the manufacturers' own ratings were somewhat optimistic, with the manufacturer-claimed playing grade of up to 160 BCF "points" contrasting with the winning machine's 133[61].

The Mark 5 also became briefly famous when it not only beat the current British chess-solving champion Dr. John Nunn five times out of six, but it also found three valid solutions to the Zagorujko chess problem, which was only supposed to have one. Andrew Page of SciSys said of the occasion that:

"It shows that chess computers have reached a level of sophistication which makes them essential for organisers of chess competitions, and for chess players who want to verify or analyse matches".

More chillingly he also suggested that:

"There are certain areas of chess in which computers are already capable of deeper analysis than humans. The day of the unbeatable chess computer is fast approaching"[62].

Levy took on a Cray again in 1984, where he played against a Cray MSC - at the time thought to be one of the most powerful computers in the world - and, over the course of two days of the challenge, which was sponsored by GEC/Dragon and was held at Brunel University, thrashed the Cray four games to nil.

The event also offered a two-day seminar on Artificial Intelligence, sponsored by Queen Mary College[63].

Computer chess continued to improve throughout the following decades, although sometimes this was as much to do with improving processor speeds and extra memory, with Sargon's authors the Spracklens suggesting that:

"90% of the improvement came from faster evaluation speed and only 10% from improved evaluations"[64].

Levy himself would be famously defeated by IBM's Deep Thought in 1989, but it wasn't until 1996 that a reigning world champion - Garry Kasparov - lost to a computer whilst playing under conventional timing conditions, although it was still said that computer wins were more down to exploiting human error than superior tactics.

However, by the mid 2000s, ever-more increasing processor power and improving algorithms meant that computers were finally reliably beating grand masters, with world champion Vladimir Kramnik being defeated 2-4 by chess program Deep Fritz.

According to Monty Newborn - former chairman of the ACM's Computer Chess Committee - that was it for chess computers and their development, stating in 2006 that:

"I don’t know what one could get out of it at this point. The science is done[65]".

The last championship featuring a computer appears to have been around 2016, but even then players like grand master Andrew Soltis were saying:

"Right now, there's just no competition, the computers are just much too good"

And whilst computers remained popular as a learning tool rather than as an opponent, there were some top-flight chess masters who would not play them any more. Referring to world champion Magnus Carlsen, Soltis reported:

"He uses it to train, to recommend moves for future competition. But he won't play it, because he just loses all the time and there's nothing more depressing than losing without even being in the game[66]"

Date created: 25 October 2019

Last updated: 03 October 2025

Hint: use left and right cursor keys to navigate between adverts.

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2026. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.