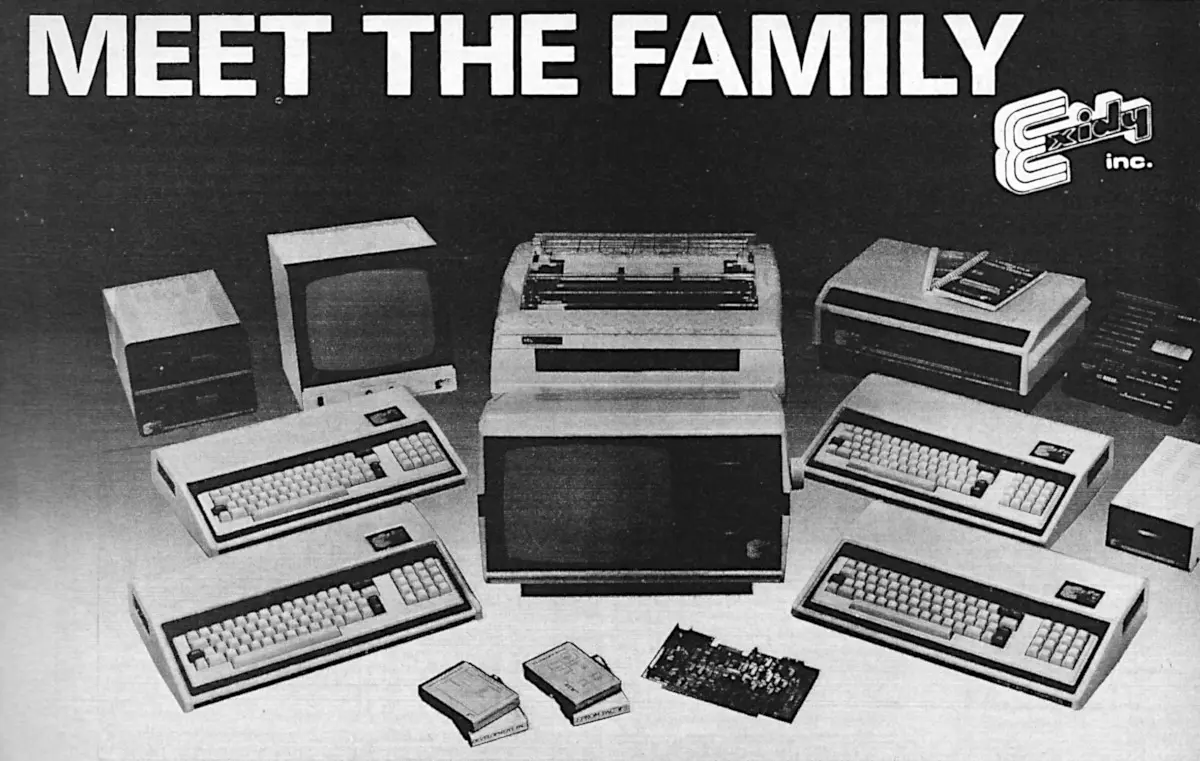

Exidy Advert - January 1979

From Personal Computer World

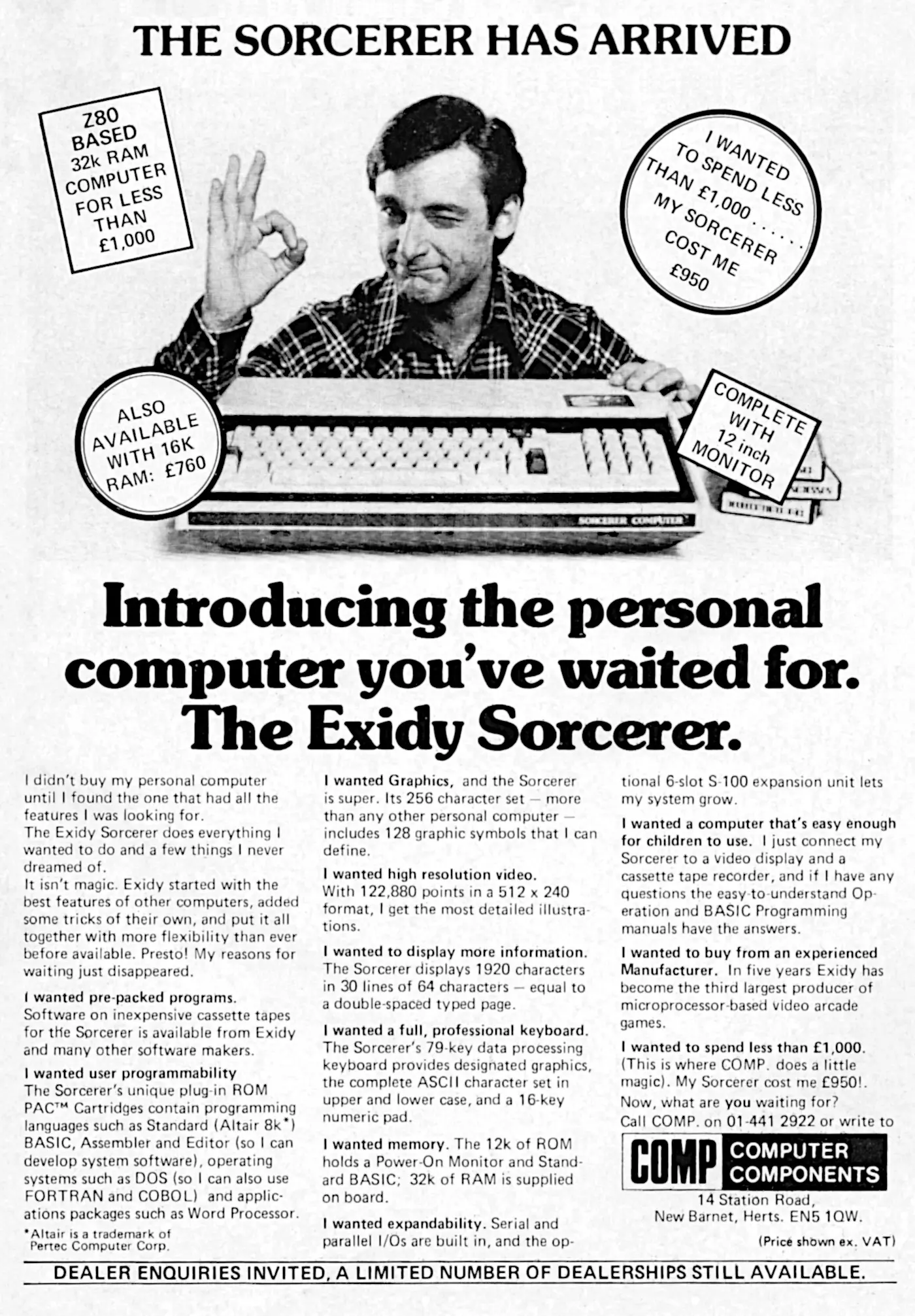

Introducing the personal computer you've been waiting for: The Exidy Sorcerer

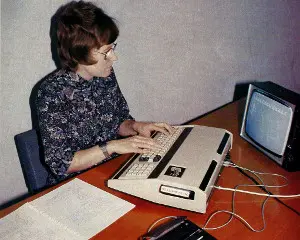

Exidy Sorcerer in use by Valerie Downes of Imperial College - a ROM pack is sticking out of the edge nearest the camera, front cover of Personal Computer World July 1979Designed by Paul Terrell as a response to the Commodore PET and the Tandy/Radio Shack TRS-80, the frankly-enormous-looking Exidy didn't last for very long in its native US, being cancelled in 1979 - the same year of this advert.

The machine itself went on though, as it was popular in Europe and ended up being produced in the Netherlands until 1983.

Running a Z80 on an S-100 bus, the Sorcerer came with Altair BASIC, 32K of RAM memory - which was still quite generous at the time - and 512x240px graphics.

The Exidy's S-100 bus wasn't expandable directly, unlike many other S-100 machines of the era, some of which had 20 or more free slots (like the Ithaca DPS-1), but there was an optional 6-slot expansion board available.

The Sorcerer retailed for £950 - about £6,120 in 2024 money.

An owner's report in July 1979's Personal Computer World by Valerie Downes, of the Department of Computing and Control at Imperial College, London, concluded of the Sorcerer that:

"it represents excellent value for money either for the home enthusiast, teacher or small businessman who wants something with expansion potential. The graphics potential is fine for both game playing and diagrams, the standard BASIC gives access to a large printed repetoire of established software, and the ROM pack [plug-in cartridges] promises easy expansion in to new languages. My only words of caution would be to wait and see how durable the ROM packs prove and how soon the projected software actually becomes available"[1].

Meanwhile, Exidy was sponsoring a competition in the summer of 1979, where the four best BASIC programs written for the Sourcerer computer would win one.

Because the Sourcerer's BASIC was compatible with Altair's 4K and 8K versions "which [had] been in use since the early days of microcomputing", it didn't require, somewhat redundantly, that software writers already had a Sourcerer to develop on.

The categories were Business, Education, Fun & Games and Home/Personal Management, and further information was available from Paul Terrell himself, at Exidy's Sunnyvale, California address[2].

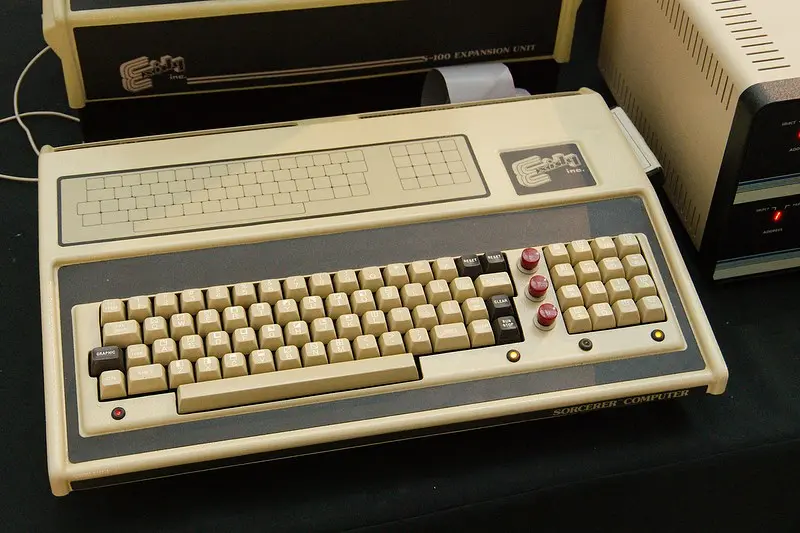

An Exidy Sorcerer at the Centre for Computing History, Cambridge, in 2018Around 1,500 Sorcerers were sold in the UK - about 10% of the worldwide total - but Exidy struggled as it claimed it was unable to make the investment required to properly break into the micro market, and so by the late summer of 1980 the company announced that it was withdrawing entirely.

After the Sourcerer had been cancelled, the rights to it were sold to fellow American company Recortec, where it was thought it might become the Personal Micro Computers Sorcerer, once Recortec had set up its PMC subsidiary to market it.

PMC was also selling EACA's Video Genie, which it was retailing by mail order as the PMC-80[3], but it had shifted only 200 units by the middle of 1980.

This compared to around 300,000 TRS-80s, the machine that the Genie was largely a clone of[4].

The Sorcerer had one significant claim to fame however: it was the machine which the first micro version of Prolog was written on.

Prolog, initially developed (in ALGOL) in 1972 by Colmeraur and Roussell, became one of the favourite language of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) community in the early 1980s, along with Lisp.

Prolog was ported to the Sorcerer by Frank McCabe and Keith Clark of Imperial College, London, in 1979.

As well as version for IBM's PC, Apple and Osborne machines, the pair even produced a version for Sinclair's 48K ZX Spectrum. Clark said of the Sinclair move that

"For a long time Clive didn't show much interest in Prolog, then he suddenly became very enthusiastic. Sinclair is now devoting quite a lot of effort to challenging the Japanese Fifth Generation project with its own work in AI - particularly now it has set up its Metalab research facility"[5].

The language seemed to remain popular enough that there was a further port for Acorn's BBC Micro at the end of 1985.

Written by Logic Programming Associates of London - the same team, albeit re-named, which had produced the Spectrum version, the new version - known as MicroProlog - was available on a 16K ROM.

This was considered an impressive feat given Prolog's usual memory requirements[6].

Meanwhile, the question of what exactly the "fifth generation" was was answered on the final ever episode of the BBC's Micro Live, where Lesley Judd and Fred Harris explained it thus:

The 1st generation was room-sized valve computers dating from the 1940s and up, the 2nd generation was the first to use transistors, in the 1950s, and the 3rd generation was the integrated-circuit/CPU micros of the latter half of the 1970s.

The family of Exidy computers, from Personal Computer World, January 1980

There was some confusion about what exactly the fourth generation was, as the term appeared to have been retro-invented after the Japanese started talking about their fifth generation.

However it could at a stretch include VLSI - Very Large Scale Integration - chips such as that being developed by Sinclair at his Metalab research outpost, where an entire computer could run from a single chip.

The fifth generation, according to the companies in Japan that were working on it, had a specific list of requirements that included Natural Language processing, Machine Learning & Reasoning and Robotics/Computer Vision.

There were similar, but not-necessarily-overlapping, generational stages for software, with first being the ones and zeros of machine code, second being assembly language, third being languages like Cobol, Fortran or BASIC, and the fourth being the fashion in the latter half of the 1980s for applications that themselves generated code - the so-called 4GL languages like Informix[7].

The fifth generation in software was said to be a goal of a program that could solve any problem given a set of constraints, rather than being programmed to solve a specific problem.

Research on this was abandoned in the early 1990s as it became apparent that solving open-ended questions could not be automated as it still required the "insight of a human programmer"[8].

Meanwhile, in March 1987, the UK's answer to 5GL - Alvey - was being wound up, and further funding from Europe for 5GL was cancelled as the UK was considered to be "dragging its heels".

The Alvey program was a £15 million government project which bought together Imperial College London (home of Valerie Downes, above), the University of Manchester, ICL and Plessey, and which intended to culminate in the construction of a full fifth-generation language.

This extended from work started in the early 1980s at Imperial on "Alice" - the Application Language Idealised Computing Engine - which was a parallel computer built around the Inmos Transputer.

As of 1987, Alice had 16 processing elements, each of which contained five Transputer chips and 128K memory, plus an additional 16 storage elements, each of which had 2Mb of RAM.

The whole thing was wired together with "a sophisticated electronic switching network" and fronted by an entire ICL 2900 mainframe.

Alice ran Occam - Inmos's custom Transputer "operating system" as well as a high-level language developed by the University of Edinburgh called Hope.

This was a new declarative language - along the lines of Prolog - which was aimed specifically at artificial intelligence and the "expert systems" that were all the rage at the time.

Another area that it was thought parallel processing would exceed was that of Natural Language Processing, where it was considered that progress "had been limited by restrictions on available computer power".

Alice and Alvey weren't alone however, as Inmos was already shipping its own IMS-B003-1 cards for the IBM PC whilst Japanese company Meiko was shipping its Transputer-based "Computer Surface" device, which was said to rival the processing power of a Cray 1[9].

Date created: 24 November 2019

Last updated: 22 October 2024

Sources

Text and otherwise-uncredited photos © nosher.net 2024. Dollar/GBP conversions, where used, assume $1.50 to £1. "Now" prices are calculated dynamically using average RPI per year.